Tag : anxiety

January 25, 2021 by admin

Cohabiting in a Pandemic

KIRA YATES, 23

One night in January, we saw a rat in my boyfriend’s kitchen. We heard it first, strutting between the pots and pans and knocking spoons off the countertop. Then, it emerged. We watched it waddle across the floor and burrow beneath the sink, fearless.

We gave it a name: Big Boy.

“Oh yes,” my boyfriend’s landlord admitted. The centuries-old farmhouse, located at the border of Cambridge, was no stranger to pests. The walls were thin and the rooms were drafty, full of holes to patch and fixes to be made. The landlord tutted and poked at the fire in the woodstove.

“We need to get rid of them,” Michael said, “They’re eating the food in the pantry and—”

“Oh, don’t mind the boys, Michael!” his landlord chuckled, shuffling the Sunday paper in his hands.

That night, we drove through the slushy city snow to my apartment with another pile of Michael’s clothes in the back seat. “I just—” he paused and smirked at me. We stared at each other, wide-eyed: “Don’t mind the boys, Michael.”

And just like that, I knew that I would never let him sleep next to Big Boy again.

On February 1st, we ate Chinese food on the rug in the living room of our new apartment, because that is what young couples do in movies and because we didn’t own any furniture yet. Our muscles were tired from carrying boxes up and down the stairs, from finding water glasses buried beneath cutlery and pie plates. We listened to a podcast about a new virus in China, and remembered the swine flu a decade before. “I had it,” I told Michael. “In the sixth grade, I brought it home to New Hampshire from a Massachusetts mall.”

“It was just a fever, like a little flu,” I added. I took another bite of lo mein and lay on my back. A moment later, Michael joined me. We stared at our living room ceiling, white and blank, like it was the night sky.

“What if we don’t get along?” I asked.

“We won’t,” he answered. “I think that’s part of it. Think of it as a social experiment.”

As March wore on, the trains grew less crowded. The beginning of my day had been punctuated by being pressed against the window of a train car, steeping in the smell of perfume and baby food and the fragile cardboard scent of grocery bags from Trader Joe’s. And then one day, all the people who owned cars grew scared enough to drive them. The last of us on the train forged a sort of camaraderie— the bond of those who had no other choice.

“I feel so lost,” I told my mom over the phone as I walked home from the train.

“I know, baby,” she answered. “Part of that is the world. And part of that is being 23.”

Michael worked from home even before the pandemic, and each day I returned from work to find him waiting for me. I would close the door, breathe in the smell of home, and collapse onto his chest before my work bag slid off my shoulder and onto the floor.

At night, we would ask into the dark, “Can you sleep?”

Undoubtedly, the other would answer, “No.”

Google automatically suggested a chart of virus data by state on the Covid Wikipedia page whenever I tapped on the search bar.

We took turns panicking. One read new articles while the other cupped their face in their hands, snorting in disbelief that we had front row seats to the end of the world. The scariest headlines, featuring droves of unmasked protesters at conservative political rallies, reminded us of Michael’s old landlord: “Don’t mind the boys.”

When, we asked, would someone “mind the boys?” It was like watching a house catch fire, only to hear the trapped occupant share how much they loved the smell of barbecue.

As the months wear on, and the virus continues its rampage, I have no great insight to offer. I refuse to allow the deaths of over a million people worldwide be a channel for my self-discovery. No, being lost in an age of loss is how I am spending my 23rd year, and likely my 24th. We’ve been forced to make a home in it—all of us. May we always be so lucky as to find love waiting for us at the door.

Kira Yates, a writer who works in development at a Synagogue in Boston, is a former Lilith Intern.

- No Comments

October 23, 2020 by admin

Cloroxing Away My Fear •

“You’re driving me crazy,” my mother says, after a walk around the neighborhood. I’ve just yelled at her for touching her insufficiently sanitized phone after washing her hands.

I know, I think. I’m driving me crazy too.

“Why can’t you trust that it’s clean?”

I want to trust—that would make everything so much easier. But my anxiety is not a switch I can simply turn off. And it isn’t unfounded, either. I have spent almost a quarter of my life fighting to regain the control over my body that Lyme Disease has taken from me. Now I am battling not only the invaders inside of me, but also the threat outside my door, and my only defense is the jumble of cleaning products in my kitchen cabinet. But unlike my Lyme treatments thus far, these chemical concoctions are real, foolproof germ-busters. If I use them enough, they will work.

I look at my mother. “I know it’s irrational,” I tell her. “But please—can you just humor me?”

She sighs, nods, and gives me a hug. She wore that shirt outside, my brain shouts. But I hug her back, gingerly, before changing my own clothes and lathering my hands with extra Mrs. Meyers.

ARIELLE SILVER-WILNER on the Lilith Blog

- No Comments

April 6, 2020 by admin

Turning Days of Distancing into Days of Reflection

Progress is an American value. We are acculturated to propel—socially, professionally, economically—which makes sheltering in place excruciating. For me, not moving forward is as good as moving backwards.

So, how can we navigate this temporary suspension of life as we know it? Some folks are turning this time into an opportunity to begin exercising, bond with family and pets, clean closets, or garden. Others are re-hanging holiday lights. I am reliving the Days of Awe.

- No Comments

April 6, 2020 by Nechama Liss-Levinson

Food for Thought on Passover

In some ways, I have always been a gastronomic Jew, that is, my Jewish identity intertwined with eating and enjoying traditional Jewish foods, like chicken soup with knaidels, noodle kugel and mandelbread. I knew in my heart that for some of us, these foods were our “madeleines,” the tastes, smells and memories that connect us with our past.

Years ago, after my mother died, I would wander down the aisles of the supermarket at Passover, looking at the lovely stalks of fresh asparagus, the bags of tiny marshmallows, the chocolate covered orange peels and the matzah redolent of matzah brei and I would silently weep, missing her presence.

- 1 Comment

April 22, 2019 by Rebecca Katz

Anxiety Nights II

Anxiety has been a familiar companion in my life. Starting in high school, I have used tv as an effective and addictive coping mechanism for anxiety. Bedtime is a particular battleground for my anxious mind.

I have to learn how to self-soothe without TV.

(Previously: “”Hello, Anxiety, My Old Friend” and “Anxiety Nights I“)

- No Comments

April 3, 2019 by Rebecca Katz

Comic: “Anxiety Nights”

Anxiety has been a familiar companion in my life. Starting in high school, I have used tv as an effective and addictive coping mechanism for anxiety. Bedtime is a particular battleground for my anxious mind.

I know mindful breathing, reading, and meditative tapes are the healthy way to transition into sleep. But watching “Bob’s Burgers” is so much easier.

(Previously: “Hello, Anxiety, My Old Friend“)

- No Comments

January 10, 2019 by admin

Synagogue Anxiety

I have noticed that the word “itchy” comes up a lot when I talk about my synagogue anxiety. I think it goes back to the excitement of buying a new “temple” outfit every year. I’m a 1980s kid, and in my mind I’m still sitting in a pew, dressed up in a brandnew Benetton sweater dress, purchased for a crisp fall morning that was still many, many weeks away.

There I am, packed into a pew with my similarly bored family, shvitzing like crazy, gawking at the garish makeup on the women around me, and counting the minutes until we would all be out of our misery.

I’m an adult now, so no one can make me wear a sweater before the first morning frost. There’s no reason I can’t go as far away as possible for the yomtoyvim. In 2016, for instance, I spent Kol Nidre in a London pub with one set of lefty Jewish friends and “broke the fast” at a North London Chinese buffet with a couple of the Jewdas folks (no, Jeremy Corbyn wasn’t there). In between these celebrations, I communed with the mummies at the British Museum and reveled in my extreme lack of angst. But did I really have to travel of thousands of miles away from friends and loved ones to escape my problem with Jewish worship?

In 2018 my feelings around Yom Kippur got notably angrier. I may have raised a few eyebrows when I tweeted before Kol Nidre that I would not be humbling myself before a god who would allow a childabusing monster into the most powerful office in the world. Hashem? F that dude, I tweeted, with my usual subtlety. I didn’t bother to move my therapy appointment so it wouldn’t overlap with pretending to care about synagogue. As I walked down the street in clothes far from itchy, I felt defiant: let the entire Upper West Side know I wouldn’t be groveling before any judge, Heavenly, District Court or Supreme.

And yet, I still missed something. Starting in the late 1880s, radical Jews started organizing Yom Kippur balls, epic parties meant to demonstrate the participants’ emancipation from what they saw as old fashioned and stultifying tradition. As Eddy Portnoy notes, what was essential to those balls was first, that they were communal affairs and second, those participating had something to rebel against.

So where does that leave the solo abstainer a hundred years later?

ROKHL KAFFRISSEN, “Caught Between Skepticism and Yearning on the Holidays,” The Lilith Blog, October 10, 2018.

- No Comments

June 19, 2018 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

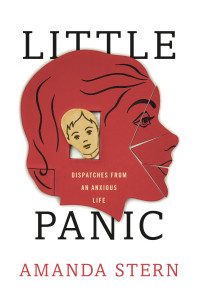

Dispatches From an Anxious Life

The world never made any sense to Amanda Stern–how could she trust time to keep flowing, the sun to rise, gravity to hold her feet to the ground, or even her own body to work the way it was supposed to?

The world never made any sense to Amanda Stern–how could she trust time to keep flowing, the sun to rise, gravity to hold her feet to the ground, or even her own body to work the way it was supposed to?

In her memoir Little Panic: Dispatches from an Anxious Life, Amanda describes this feeling. Deep down, she knows that there’s something horribly wrong with her, some defect that her siblings and friends don’t have to cope with.

Growing up in the 1970s and 80s in New York, Amanda experiences the magic and madness of life through the filter of unrelenting panic. Plagued with fear that her friends and family will be taken from her if she’s not watching—that her mother will die, or forget she has children and just move away—Amanda treats every parting as her last. Shuttled between a barefoot bohemian life with her mother in Greenwich Village, and a sanitized, stricter world of affluence uptown with her father, Amanda has little she can depend on. And when Etan Patz, the six-year-old boy down the block from their MacDougal Street home disappears on the first day he walks to school alone, she can’t help but believe that all her worst fears are about to come true.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...