by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Dispatches From an Anxious Life

The world never made any sense to Amanda Stern–how could she trust time to keep flowing, the sun to rise, gravity to hold her feet to the ground, or even her own body to work the way it was supposed to?

The world never made any sense to Amanda Stern–how could she trust time to keep flowing, the sun to rise, gravity to hold her feet to the ground, or even her own body to work the way it was supposed to?

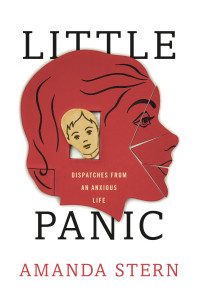

In her memoir Little Panic: Dispatches from an Anxious Life, Amanda describes this feeling. Deep down, she knows that there’s something horribly wrong with her, some defect that her siblings and friends don’t have to cope with.

Growing up in the 1970s and 80s in New York, Amanda experiences the magic and madness of life through the filter of unrelenting panic. Plagued with fear that her friends and family will be taken from her if she’s not watching—that her mother will die, or forget she has children and just move away—Amanda treats every parting as her last. Shuttled between a barefoot bohemian life with her mother in Greenwich Village, and a sanitized, stricter world of affluence uptown with her father, Amanda has little she can depend on. And when Etan Patz, the six-year-old boy down the block from their MacDougal Street home disappears on the first day he walks to school alone, she can’t help but believe that all her worst fears are about to come true.

Stern spoke with Lilith Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the peculiar terror that dominated her childhood, and how her eventual understanding—and acceptance—of these early fears has finally earned her a measure of peace.

YZM: Why do you think it took so long for anyone to diagnose what you were suffering from?

AS: The landscape of focus wasn’t the same as it is today. The adult world was much more attuned to what they could see rather than what they couldn’t. Bad grades: visible; mental anguish: invisible. My teachers and testers seemed to recognize my anxiety, but no one spoke to me about it. Adults have the power to keep a child from knowing herself, and without forecasting how the end result might play out (badly), they withheld who I was from me. It was a different time; our parents didn’t parent the way they do today. Not to mention, anxiety and panic weren’t part of the cultural conversation, so the signature features that today would be so obvious weren’t taken as seriously.

YZM: You wrote that in middle school, you were exposed to a kind of casual anti-Semitism; how did this contribute to your anxiety and sense of yourself as an outsider?

AS: That was my first experience with anti-Semitism, and quite honestly, I thought it was narrow-minded and sad. But it did alert me to a difference to which I hadn’t been entirely aware. I never considered that I looked Jewish, and when I realized that I became a bit more self-conscious of myself, but for reasons I can’t quite explain, it didn’t exacerbate my anxiety. It simply made me more attuned to prejudice and heightened my awareness that fearing difference was one more thing I didn’t have in common with the general population. “Otherness” is home to me. It’s what I’ve always gravitated toward, so in a sense, it helped me define who I was; that I was not a person who shamed others, or who cared for that matter whether a person had cancer, was deaf, wore a prosthesis, or was another race or religion. It simply cemented my connection to those who, to me, seemed most real and alive.

YZM: The memoir is constructed as a series of small essays, moving back and forth in time. Was this your overall vision for the book from the start or did you write the essays first and only later see them coming together in book form?

AS: I set out to write an autobiography of an emotion; to chart the lifecycle of anxiety as it moved through me since I was an infant. My overall vision for the book was to have the IQ tests and personal evaluations play a bigger role than they ultimately did, and while the shape came together as I wrote, when I finished I felt very much as though the feeling inside me matched the final product.

YZM: You’ve written a novel for adults and eleven children’s books as well as this memoir; can you comment on writing across genres?

AS: Writing books for children is like taking your brain to a playground. It’s incredibly freeing, and while it’s a bit less spontaneous than writing for adults, because there are more restrictions, it’s really helped flex my thinking. In the beginning it was a bit of a struggle. I would carry the kids voice over to the adult work and then I’d fear I’d lost the ability to write a sophisticated sentence. It reminded me of a guy I dated who was a serious actor who was cast in the Cirque du Soleil. He worried relentlessly that the cheesiness of the show would erase everything he’d ever learned about being a classical actor. That’s sort of how I felt, but that goes away, and you learn that your skillset doesn’t get erased.

YZM: What would you like readers to come away with after reading this book?

AS: My hope is that readers with anxiety will come away feeling less alone, and less ashamed to feel what and how they do, and that readers who don’t suffer from anxiety will realize that mental illness is not something to be fixed. It’s a condition of being human. Despite our opposing political viewpoints, and values, we’re all in this together. There is no one right way to be a human being, and if I can get any point across it’s that being ashamed of your or anyone else’s humanness will weaken, not strengthen who you already are.