Tag : yiddish

January 26, 2021 by admin

Those Women of Valor •

Looking at Americanization and how women creatively grappled with relocation is the subject of “Immigration and Adaptation: Jewish Women of the Lower East Side,” an illustrated talk by historian Annie Polland. Keeping the Sabbath, an important marker of Jewish identity for many women, was a great challenge when they observed a different Sabbath from their new neighbors. Men and children—especially eldest children—were often working in sweatshop

conditions, and women who stayed home were business people, renting rooms and caring for boarders in their homes. And having a Friday night Shabbat meal has always required labor and forethought. Although they wouldn’t have used the term at the time, figuring out how to be secular or cultural Jews was one of the great accomplishments of these women. The talk is co-sponsored by the American Jewish Historical Society at the Yiddish Book Center.

yiddishbookcenter.org/events.

- No Comments

January 26, 2021 by admin

Women’s Voices in Yiddish Folksongs

A new project analyzing the Yiddish folksong tradition takes advantage of major collections that are now a click away online. Itzik Gottesman, one of the project’s creators, is a grandson of Lifshe Schaechter-Widman and son of the poet and artist Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman. He says, “Not only can much about Jewish life in Eastern Europe and immigrant life be learned from these singers, but the women’s voice, so suppressed in traditional Jewish life, takes front and center when it comes to the Yiddish folksong.”

yiddishfolksong.com

- No Comments

January 25, 2021 by admin

Honey on the Page

Yiddish children’s literature, created all over the world, largely during the period between the two world wars, includes writers who considered themselves secularists, and nevertheless shared stories about the magical aspects of keeping the Sabbath; as socialists they wanted to encourage workers not to let capitalists own them seven days a week. On the occasion of the publication of Honey on the Page: A Treasury of Yiddish Children’s Literature, editor and translator Miriam Udel, was interviewed by Laura Shaw-Frank, on the feminist underpinnings of her research on Yiddish children’s literature. Many female writers still did not have “a room of their own,” so there is a limit to the number of female authors she was able to include. But she highlights some iconic female protagonists such as Dovid Rodin’s Shprintse and Kadya Molodovsky’s Olka. This webinar was co-sponsored by JOFA, Maharat and Svivah.

facebook.com/watch/?v=1734182590079696

- No Comments

October 23, 2020 by admin

Children of the Mother Tongue

There was a time when Yiddish was a language like any other. It was the mother tongue of millions: There were newspapers in Yiddish, novels in Yiddish, movies in Yiddish and children’s literature in Yiddish. But Yiddish has disappeared so quickly and is employed in such limited contexts that we can hardly imagine that for at least a certain period of time it was a language that encompassed all aspects of daily life. The language was annihilated under such tragic circumstances that we can depict it today only as part of a nostalgic “Yiddishland” where people were poor but happy, miserable but hopeful, innocent but wise.

Honey on the Page: A Treasury of Yiddish Children’s Literature (NYU Press, $29.95), an anthology of Yiddish children’s stories collected, translated and edited by Miriam Udel, upends all these clichés. The only element the stories have in common is that they were written in Yiddish and for a young readership— they vary in length, subject matter, and genre. Some are boldly realistic, taking on issues like death, poverty and exile. Some take place in imaginary countries and involve the magical and mystical. Some are a combination of all the above. For instance, the first story in the anthology, “A Shabbat in the Forest” by Yaakov Fichmann, reflects the harsh reality of poor peddlers who were forced to spend the weekdays away from their family, but quickly turns to the magical and fantastic.

Yiddish is often referred to as Mameloshn—the mother tongue, but the vast majority of its authors are male, both in children’s and adult literature. In her introduction, Udel explains that she attempted to even out the picture somewhat by including as many female authors as possible. While this is an important and admirable step toward a more gender- balanced canon, Udel seems to have included pieces that would otherwise not have been not deemed worthy of translation and publication, such as Malka Szechet’s “What Izzy Knows about Lag Ba’Omer,” a didactic story with little literary or even informative value.

The gender gap is also very apparent when we consider the protagonists of the anthologized stories. The vast majority are male, with women and girls often playing only supporting roles. One particularly notable female protagonist is Shprintse from Dovid Rodin’s “An Unusual Girl from Brooklyn,” excerpted here—a novel about a girl who is so immersed in the books she reads that they begin to come to life for her. I was intrigued enough to seek out the original, available online, and hopefully one day available in translation as well.

As this anthology showcases, children’s writing was taken very seriously by Yiddish writers. The best Yiddish and Hebrew authors, such as Yaakov Fichmann, Levin Kipnis, Sholem Asch and Kadya Molodowsky, dedicated much time and effort to their younger readers. The fact that these pieces can be enjoyed today is a testimony to their enduring quality. When these writers composed their stories, they imagined a large, eager, diverse readership. Udel’s superb work of selection and translation breathes new life into these works, fulfilling the wishes of their authors, albeit in different form.

The book takes its name from the tradition of giving children honey-covered letters so they will associate Torah study with sweetness. The stories in this anthology indeed read as artisanal candies with flavors both familiar and foreign, enticing and exotic.

Tali Berner teaches at the Program for Child and Youth Culture at Tel Aviv University. She holds a PhD in Jewish history from The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- No Comments

June 25, 2020 by admin

Jewish Before I Was American

My grandparents, my aunt, uncle, two cousins, my parents and I lived in one Williamsburg, Brooklyn brownstone until the early 30s. I spoke Yiddish before I learned English. I was taught to read and write in Hebrew and in Yiddish. Aunt Dora generously shared her public library books of Yiddish poetry and stories with me. We read daily Yiddish newspapers. “Yiddishkeit” was part of my everyday life, not just reserved for Shabbat and holidays.

I wrote about my early years in my first juvenile novel {Ruthie, Meredith Press, 1965). Thinking back to those Williamsburg years, I realize that I became a Jewish person before I became an American person.

Norma Simon is the author of more than 50 children’s books, 13 on Jewish holidays or subjects; 2 new ones due out in 1997 on Passover and Hannukah (HarperCollins). She moved to Cape Cod 27 years ago.

- No Comments

April 23, 2020 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

A New Translation of a Yiddish Comic Gem

If you crossed Helen’s Fielding’s Bridget Jones’s Diary with Nathanael West’s Miss Lonelyhearts, you might end up with Diary of a Lonely Girl, or the Battle Against Free Love (Syracuse University Press, $19.95) written by the Yiddish writer Miriam Karpilove and recently translated by Jessica Kirzane. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough talks to Kirzane about how she stumbled upon this singular writer and why her work still matters today.

- No Comments

April 20, 2020 by admin

Making Yiddish Hip, Heymish & Hot

For Eleanor Reissa, the stage is often crowded. No matter what role she is playing or what tunes she is belting out, Reissa’s late parents and grandparents and other Holocaust survivors she has known are always present, right next to her.

“You don’t know it when you look at me, but you are seeing them,” she says.

Reissa is an acclaimed actor, singer, director, impresario, writer, comedian, translator, choreographer; she skates between the Yiddish and English worlds, at home in both. At heart, she’s a storyteller. Sometimes she’s telling her own story and that of her parents, Ruth Hoff and Chaskel Schlusselberg. Other times, she’s retelling others’ stories, in the theatrical roles in which she is cast, channeling her craft.

“It’s my interpretation of someone else’s story, my feet slipping into someone else’s shoes. Their shoes, but my feet.”

Those feet are graceful and energetic. She recently danced onstage in the Broadway production of “Indecent,” and sways her hips in sequined dresses while singing in her own cabaret-style shows or accompanying bands. Music seems to lift her from mournfulness. She has managed to turn the hole in her heart into art. Amidst the sadness, she’s also very funny.

I’ve followed her over these last months, as she was prepping backstage in a Boston theater, taping a podcast in a Manhattan studio, singing American and Yiddish standards at City Vineyard, chatting in her sunny apartment in an Upper West Side brownstone and in cafes and on calls. The voice is steady, authentic, reflective and resilient. She dives deep, and more than once her words bring on tears. She speaks English with the warmth, zest and soulfulness of Yiddish, her first language.

That she loves what she does is clear, and these are busy times for Reissa. She’s directing Paddy Chayefsky’s “The Tenth Man” for the National Yiddish Theater Folksbiene, in an original translation into Yiddish that she did with Harvey Varga. “Der Tsenter,” The Tenth, opens in May. She recently finished a starring run in “We All Fall Down,” Lila Rose Kaplan’s new play that premiered at the Huntington Theatre Company in Boston. She’d been traveling to New York, Philadelphia and Boston with Paul Shapiro’s Ribs & Brisket Revue presenting “The Music of Mrs. Maisel”—described as American standards with Yiddish flair—with tunes of the Barry Sisters, Connie Francis and others. She sings in English and Yiddish in a voice that’s torchy and sweet.

Internationally, she travels as vocalist with Frank London and his Klezmer Brass All-Stars and says, “I feel like I’m in a rock band, in Yiddish.” She had planned to highlight a show in April at Symphony Space, “Zol Zayn: Yiddish Poetry into Song,” alongside London, Anglo-Indian percussionist Deep Singh, Radical Jewish Culture guitarist Yoshie Fruchter and others.

Reissa is a bridge between the generation of wonderfully talented Yiddish actors and musicians who grew up immersed in Yiddish, and those of a younger generation who have rediscovered the language anew and bring to it a hip sensibility. She shares the polished old school talent and the vibrancy of the new. She’s very much a force in reigniting the Yiddish imagination.

And in English, she recently appeared in the HBO miniseries, “The Plot Against America,” as Philip Roth’s grandmother (a character not in the book; the mother of Winona Ryder and Zoe Kazan on screen). She plays opposite Ron Rifkin in a new movie by Eric Steele to be released later this year: “Minyan,” set in 1987 Brighton Beach.

“Sometimes I feel like Little Jack Horner. I stuck in my thumb and pulled out a plum,” she says. “Holy mackerel. Look at who I get to work with. How great to be in the company of such excellence.”

“She is an extraordinarily gifted artist” says Melia Bensussen, artistic director of Hartford Stage, who directed the recent Huntington Theater production of “We All Fall Down.”

“While many in the theater are capable of practicing different aspects of the craft, it’s extraordinary for someone to do so at Reissa’s degree of expertise and accomplishment.” When I ask if Bensussen senses those generations of loved ones that Reissa describes as surrounding her on stage, she laughs and says, “Very much so. There’s an energy and fullness in everything she does. I can feel her history.”

To Reissa, the theater is about “the community that has stood shoulder to shoulder to create an imagined world that didn’t exist before and the audience who shares the anonymity of the darkness together and laughs and weeps as one. That’s different from books or other art.”

“I try to tell the truth in my work,” she says “I come from people who felt the truth was dangerous. It was better not to tell the truth. I didn’t know that was lying.”

Born in the East New York section of Brooklyn, her parents were about to name her Alta Rishe Schlusselberg, but a doctor intervened, and someone suggested Eleanor, perhaps for Eleanor Roosevelt. Both of her parents had been previously married in Europe, with families. Her mother and her mother’s parents survived by fleeing from Bilgoraj, Poland, to Uzbekistan and her mother’s first husband abandoned them. Her father’s first wife and daughter were murdered in 1942, and he survived Auschwitz. Her parents were cousins who met after the war in Ulm, Germany, and married in the U.S. One half-brother lived with them in Brooklyn, and her father’s son—whose existence she learned about only when she was about 13—was in England. Her parents worked hard in New York; he in a paintbrush factory and she in a garment factory. When Eleanor was six they divorced.

Reissa attended public schools, and praises her teachers, many of whom were Jewish men trying to avoid the draft. For about 10 years beginning when she was three, she attended ballet school weekly, with a Russian teacher. Her mother sewed beautiful costumes for their recitals.

“That was a beginning,” she says. Her mother took her to see “Swan Lake” at Lincoln Center and her father took her to her first Broadway show, “The Zulu and the Zayda” set in South Africa. Her own first production was “Peter Pan” in third grade. Later on, in seventh grade, she played Emily, who comes back from the dead, in “Our Town,” a theme that has carried over in her career.

All along, her plan was to become a math teacher. A tough course in calculus at Brooklyn College made her reconsider. In those days—the mid-1970s—she got involved in politics and street theater. The first Off-Off Broadway play she acted in was “The Horrors of Dr. Moreau,” adapted from an H.G. Wells novel. Then, she was still Eleanor Schlusselberg, not yet thinking of theater as a career.

She has always worked hard, and enjoys it. At 16, she heard of a job opening for a switchboard operator at a hotel in the Catskills. To get the job, she went to a neighboring hotel and asked their operator to teach her. When she showed up for her interview already trained, she was hired. Throughout her career, she has pushed herself toward such boldness. During the summers and on weekends through college, she supported herself—her father got her a car and she moved into her own apartment in Brooklyn at 17—by waiting tables in the Catskills, a step up from staffing the phones. Proudly, she says, she could carry 16 main dishes at a time, just like her male counterparts.

One of the waiters was stage-managing a national tour of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” and invited her to join their cast. Until then, her acting had been in experimental theatre.

Eleanor Reissa and Cilla Owens with Paul Shapiro’s Ribs and Brisket band, photographed by Joan Roth,

December 26, 2019.

She says she didn’t know what she was doing, but auditioned for a small role and got it, along with an Actor’s Equity card and salary for six months.

“I never waited tables again,” she says.

Back in New York City after having a great time on the road, she saw an ad for a musical in Yiddish at Town Hall starring Mary Soreanu, “Rebecca the Rabbi’s Daughter.” She auditioned and got a role in the chorus in 1979.

“I didn’t know enough to know that I didn’t know anything,” she says, repeating a refrain she voices a lot in talking about her career. Just as the cast was scheduled to go on tour after a successful run, Mary Soreanu got sick. Her husband, the producer, was about to cancel the tour when Reissa stepped up and suggested that she could play the lead. Offer accepted. “That put me on the little Yiddish map.”

“Yiddish has reminded me that no matter how far I have wanted to run away, it kept me exactly where I belong, as a testament in some way to my family.”

Soon after a gig at a regional theater in Alaska, she met Zalman Mlotek, then a musician and now artistic director of the National Yiddish Theater—Folksbiene. He invited her to join him in a Yiddish concert. That led to their collaborating on several shows along with Moshe Rosenfeld, including “The Golden Land,” a musical revue they created for the Forward’s 85th anniversary, and in which she performed.

“This was the first time the youth had risen up; a talented batch of American Yiddish speakers were taking over the stage.”

The producing team had a kind of break-up, so she was surprised when she was called to do another show with them, a Yiddish revue called “Those Were the Days.” In another of her bold moments, she negotiated to become director and choreographer.

“I wanted my opinion to count,” she recalls. “It doesn’t count when you are an actor.”

She put together a strong cast, with Bruce Adler, Mina Bern and others, and she also acted, sang and danced. Producer Manny Aizenberg came to see it, and she soon learned that her first directing job was going to Broadway. In 1991, she was nominated for a Tony.

Once, the great choreographer Jerome Robbins came backstage after a performance, visibly moved by the production. She then wrote to thank him and his assistant for coming, and suggested that if they ever could use her to be in the room as they worked, she’d love that. Robbins was then exploring his life in dance for a still unfinished piece called “The Poppa Project” and invited her to attend rehearsals. “I sat in that room for two weeks,” she recalls, “just watching the most beautiful thing ever created, every day.”

In the mid-90s, she got involved with the Folksbiene, and she and Mlotek became co-artistic directors, replacing the old guard. They pitched themselves as the new wave, wanting to bring new life to the Yiddish theater. One of their first shows was a modern play that Reissa wrote, “Zise Khaloymes,” Sweet Dreams, adapted into a musical.

“I was determined that Yiddish be seen as a language that anyone can speak,” she says, as they tried to present Yiddish theater that was contemporary, multi-ethnic and multi-generational. While she stepped away from the co-directing role a few years later, she says she is grateful to remain connected to the company.

Since then, she has directed a lot—including co-creating with Seth Rogovoy, directing and performing in Carnegie Hall’s sold-out “From Shtetl to Stage” program last year—although the beginnings weren’t easy.

“I had a big mouth. That was not attractive, because I was a woman. I got too excited, too passionate. I didn’t think anyone was listening. They weren’t,” she says, adding, “My mother was a strong, opinionated, self-sufficient woman. Not happily so. She wished someone would have taken care of her, but she took care of herself. That’s where I come from.”

“I had to stand on my own shoulders, and they weren’t very high,” she says. “There weren’t a lot of women directors. I fought very hard.” Over the years, she has learned to temper her anxiety and passions, gaining patience and trust. As she explains, “I was weak and I pressed hard. Now I am stronger and don’t have to press so hard.”

“I didn’t go to Julliard or the Yale School of Drama. I learned by trial and error and observation so it took a little longer,” she says. “That is how I have lived. I raise my hand and then try to find out what the answer is. I want to play. I want to be picked. I want to be seen. I like the challenge of it all.”

She watched sports a lot as a child, emulating her older brother. Her first dream was to be a football coach—she wanted to be the first female football coach. “I wanted to inspire and direct men. When I think of myself as a director, I came as close as I could to doing that.”

Recently, she published a book of six plays, The Last Survivor and other Modern Jewish Plays, some of which have been produced. These plays are all about her, she admits, and they all end with the dead coming back to life in some form.

In between directing and performing, she is now writing a book called “The Letters Project”—it’s the thing she says she now cares most about. Reissa, who is twice divorced, enjoys the solitude of her lakeside cabin in upstate New York for writing The letters refer to a collection of 60 letters that her father wrote to her mother in Germany, in German. She came upon them, as if by accident, in 1986 after her mother’s death. She didn’t know that her mother spoke German. Since she didn’t understand the German, she put them aside, to pick them up 30 years later, in 2017, when she decided to have them translated.

She learned, among other things, about her father’s life in Germany in the 1930s and about his first wife and daughter. The following summer, Reissa traveled to his town, Stryzw, in the Carpathian Mountains, and found other documents. And she learned things about her parents and about herself that she is still processing as she completes the memoir. She admits that she’s not sure if her mother left the letters for her to find, years after she and Reissa’s father divorced, and then years after his death.

“To be in front of my father’s pain and anguish and the horror of his life—I’ve spent so much time acting as though I can handle it, but in fact taking it in is really too much,” she says. “You don’t know where your journey goes. I look at the body of my work for the last 40 years and I see where I am now, in terms of every single thing that I’m doing. You could tie it up with a bow in a box, a big box.”

Reissa is more than ready to speak publicly about the Shoah. There’s much that she wants to say to students, and hopes to do so, perhaps in connection with a recent project for Yale University’s Fortunoff Archive for Holocaust Testimonies. She narrates a new podcast series, “Those Who Were There: Voices from the Holocaust,” unfolding the plainspoken stories of survivors to provide a historical record.

“I have one foot in this world and another foot in this other world. I know the survivors and know the world without survivors. I knew them, I saw them, I touched them, I love them, I can tell about them,” she says.

Reissa was raised with a sense of European Jewish Orthodoxy, with her observant grandparents living nearby. She grew up sitting upstairs in the women’s section of their shul. She used to believe in God and feel comforted by religion, but for the last decades her spiritual life has been different, spent searching for her parents, “for their spirit, their company. I felt like I wanted to connect.”

She searched for synagogues where she would feel at home, but came to see that she really didn’t believe in God. “I believe in the spirits of dead people. I do believe that the souls of the departed are occasionally accessible.”

She participates in the Jewish traditions of mourning and remembrance, and also enjoys the rituals of Passover and Chanukah. Sometimes she lights Shabbat candles. “It’s about bringing light into my life,” she says.

Always leaning toward progressive values, she says there was a time when she didn’t worry much about anti-Semitism but now feels very frightened. “When do you know if history is repeating itself ?” she asks. “When do you know if it’s time to run away? We can’t see into the future so all you can do is look at signs. The current situation scares me. I fear for our democracy and I fear totalitarianism. 1945 was 75 years ago, so the ink is still wet. It affects me a lot, daily; it colors some of my day.”

In her last show at Feinstein’s, she performed her own translation of Woody Guthrie’s “This Land is My Land” into Yiddish (substituting the Ketzkill Bergn, Catskill Mountains, for the Redwood forest, closer to the Jewish immigrant experience), expressing her deeply felt wishes for a fair, peaceful, educated and open land.

Reissa is well aware of the miracles in her life. She says, “Like Goldilocks, the shoe fits, it’s just right. I’m my own prince. That’s important. I’m single and I was kind of looking for a partner with a house on a lake. I found one and it was me. It’s really empowering. I don’t need to find someone to get me what I want. I can get it myself.”

“I have a life of enormous richness that I didn’t always recognize and appreciate,” she says. “I do now. Most of the time. I’ve had a lot of plenty.”

For Reissa, feeling her absent family nearby gives her courage.

“It makes me feel less afraid and less alone. And I feel like I come from something. Sometimes I sing to them, when I have to say the word ‘mother’ or ‘father’ or ‘love’ in a play, they come up. The images that stimulate me as an artist are them.”

Sandee Brawarsky, an award-winning journalist and editor, is the culture editor of The Jewish Week and author of several books, most recently 212 Views of Central Park: Viewing New York City’s Jewel from Every Angle.

- No Comments

January 16, 2020 by admin

Life and Art

All strong women don’t have to be saintly. Some go about corralling the money they need to survive or to gain importance in brutal or deceitful ways, just as men do, in real life and in theater.

AILEEN JACOBSON, “Maiden, Sorceress and Stepmother on Stage, Yiddish-Style,” on the Lilith Blog.

- No Comments

January 14, 2020 by admin

We All Stand Here Ironing

Tillie Olsen and her daughters, 1947. Photos Courtesy of Julie Olsen Edwards.

Tillie Olsen wrote her important stories and essays in a tradition of Jewish radicalism that insists on the struggle for economic, gender and racial justice as a burden and privilege of Jews—rooted in a history of oppression and survival, in the conviction that such experience demands empathy and activism. Devoting her writing and personal life to these values, Tillie Olsen was also the great writer of the experience of motherhood. In the unique, poetic prose of the stories, she plumbs the deepest layers of an experience that can combine overwhelming love with exhausting, demanding labor, devotion with anger, power with helplessness.

Olsen, among the most influential writers in American literature, certainly in my writing life, a maternal presence in her literary work and in a friendship that lasted from 1975 until she died in 2007. I want to claim her now not for myself, though including myself, not for the entire world, though she rightfully belongs to the multitudes, but especially for the people who struggle against injustice everywhere.

For Olsen, the conditions of our inner lives are inexorably interwoven with the material conditions of our lives in society. As she once wrote: “… not only the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, but the establishment of the means—the social, economic, cultural educational means to give pulsing, enabling life to those rights.”

In her writing and in her support for other writers, she joined the struggle.

In the great novella Tell Me A Riddle, Eva—a woman considered old then at 69—is about to die. To her husband, who for most of the story, names her out of his own contempt: “Mrs. Orator Without Breath,” “Mrs. Enlightened,” who asks bitterly, “You think you are still an orator of the 1905 revolution?” she responds: “To smash all the ghettos that divide us—not to go back, not to go back—this is to teach.”

Confined to a hospital bed with untreatable cancer, Eva is told by her daughter that a “man of God” came to her bed to comfort her. “The hospital makes up the list for them,” the daughter says, “and you are on the Jewish list.” But Eva, weak, yet still driven by her defining passion, shouts, “At once, make them go and change. Tell them to write: Race, human; Religion, none.”

Still she believed, her husband says near the end of the novella and in the last moments of her life. She may no longer be able to hear him when he finally calls her Eva, her name, and asks: Still you believed?

O Yes is her story of racial friendship and separation, a white child, a black child, friends until they reach a certain age and then, “how they sort…a foreboding of comprehension,” thinks the mother. The story was written long before Toni Morrison named an “Africanist presence” as a formal turning point in much white American literature, describing encounters between white and black characters in which a black character, “lubricates the turn of the plot and becomes the agency of moral choice.” Olsen may have sensed the nature of such moments when the young white daughter, unused to the powerful emotion expressed in a Black church they have gone to in support of her black friend, is overcome by conflicting feelings and faints. In adolescence, when the two girls have migrated to their separate worlds, the daughter cries to her mother, “Why do I have to care?” The mother caresses, trying to calm, but is thinking: “caring asks doing. It is a long baptism into the seas of humankind, my daughter. Better immersion than to live untouched.” Through the use of sentence fragments and specific cultural grammar, what Toni Morrison and James Baldwin accomplished in illuminating the poetry of Black English, Tillie Olsen has done for Yiddish syntax and inflection, forcing us to read language as more than communication formed over centuries of use but as poetry, for poetry must in part be understood as a way of finding in ordinary speech imagery and allusions that dive deep into consciousness. Words accompanying the 1994 Rea Award for Distinguished Contribution to the Short Story: ‘She [combined] the lyric intensity of an Emily Dickinson with the scope of a Balzac novel.’

In 1969, having given birth to my first child, I was seeking desperately, futilely I began to believe, for a work that would describe the sudden plunge into the deepest love I had ever known, but also the body-wide fear and paralyzing guilt that could obscure that love into periods of fog and confusion, into rages and weeping I neither recognized nor understood. Tillie Olsen gave me language to begin to name them.

In about 1975, soon after I had published my first book, The Mother Knot, a memoir about the transformational experience of giving birth and learning to mother, I received a gift from Tillie—a copy of her novel, Yonondio, From the Thirties. By then, I had read all her fiction with a wave of relief—like those enormous ocean waves at high tide which, though large, can be gentle if you are out far enough—your body sails over them, safe and amazed as you watch them crash into shore. So, reading her fiction, I was witnessing the crash—reading about the complex and powerful feelings in being a mother, far enough out not to be hurt, yet awestruck by the power of the wave. Tillie Olsen’s poetry and courage would enable me to participate in a sea of change over a lifetime of writing and teaching: the maternal voice, finally not trivialized or sentimentalized or falsified, not restricted to a “how to” or a pediatric manual mostly written by male doctors; instead, so truthful and eloquent she was driving this long-buried voice into literature.

In my now yellowed and fading paperback copy of Yonondio there was something I would learn lay at the very heart of her being. In the middle of the novel, she had inserted a note. In her characteristic tiny script, which I can hardly read today, stuck to the page with a nice red star (this was before post-its!), she crossed out a paragraph and, in the margins, wrote a note to me about how she would rewrite it. “Omit” she wrote, and added several question marks in dark black ink.

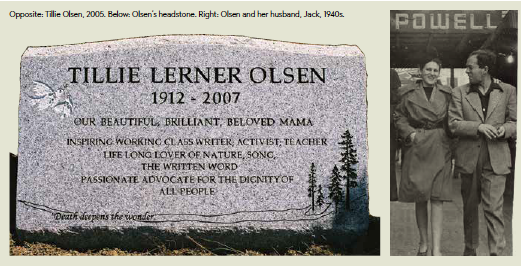

Tillie Olsen was born Tillie Lerner “in a tenant farm in Nebraska, the second of six children of Russian Jewish immigrants who left their homeland after involvement in the failed 1905 revolution. She grew up in Omaha, where her father worked as a painter and paperhanger and served as state secretary of the Nebraska Socialist Party. … In 1929 she embarked on what would be thirty years of low paying jobs (hotel maid, packinghouse worker, linen checker, waitress, laundry worker, factory worker, secretary).”

These words were written by two of her daughters, Julie Olsen Edwards and Laurie Olsen, significant because one of Tillie Olsen’s defining values was to pass on beliefs to the next generation—first to her own children, then to other writers in whose work she saw a sign of necessary voice, some in danger of being silenced by economic and political constraints. She spoke out for labor, against Apartheid and racism, against war, for women’s rights, for the protection of the earth. Like most dedicated activists, she could be fierce in her convictions, in her fury at injustice. But this was all very familiar to me. I had been raised in a family of Jewish American Communists, and this was one piece of our history, I think, that drew us together: we knew the faults of the old left— their righteousness, yes, and how wrong they were in some ways, but also the beauty of the core beliefs, the brilliant core always shining at the center of everything Olsen wrote.

Her essay, “Silences” (in a book by the same name), about the sources of literary silence through centuries of writing, is a sustaining work for every writer I know. She writes of the barriers to fullness of voice, constraints at times to coming to voice at all:

She quotes Herman Melville: “…the calm, the coolness, the silent grass-growing mood in which a man ought always to compose— that I fear, can seldom be mine. Dollars damn me—what I feel most moved to write, that is banned,—and it will not pay.” And she notes how Joseph Conrad described his creative process, unaware of the economic and gender privileges enabling him: “…I suppose I slept and ate the food put before me …but I was never aware of the even flow of daily life, made easy and noiseless for me by a silent, watchful, tireless affection.”

Photos Courtesy of Julie Olsen Edwards

Like Virginia Woolf imagining Judith Shakespeare, who as a woman could never have brought to life her genius supposing she possessed it like her actual brother, Olsen wrote of our great human loss—the lives that never came to writing, “among these, the mute inglorious Miltons: those whose waking hours are all struggle for existence; the barely educated; the illiterate; women.”

Olsen reminds us that for centuries women writers who created good and great work almost all never married, never had children, wrote under male pseudonyms— until the small trickle began in my generation, and now the whole earth begins to fill with women’s stories as some—more than before but still not enough—emerge into print.

I am seeing her now—we are walking through the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City—she is pointing out patterns in color and shape, the portraits that so compelled her; and always, no matter what I was writing at the time, she is asking me about my children—how are they, she wants to know—how old are they now? It was often my portrayal of mothers and children she commented on in my work, the complicated layers of motherhood, the “amplitude” she called it.

It was her own amplitude that enabled many writers of my generation to begin to heal the split between our writing/artist selves and ourselves as mothers, and in imagining that healing begin to glimpse the nature of the disease that had split us, turning being an artist and a mother into inherent contradictions. She never minimized the effort, knowing the battles that accompany such a desire, and she wrote the history for us, let us know by her own honesty and specificity that we were not alone. But “Nobody,” she told me during one conversation about motherhood, “has a harder time in our society than a mother who is trying to make it alone.”

Olsen had a husband, Jack Olsen, a union organizer, waterfront worker and educator with whom she raised her four daughters and shared her life until he died, but her first work wasn’t written until her children were finally in school. She still worked a daily job, so it is not disembodied imagination nor an accident of inspiration that the first line of her first published work is “I stand here ironing.”

A mother, overworked and suffering feelings of guilt toward her daughter who is having trouble in school, the eldest, the one who she depends on to help care for the others—the story ends with the final lines so many of us know by heart: “ So all that is in her will not bloom—but in how many does it? There is still enough to live by. Only help her to know—help make it so there is cause for her to know—that she is more than this dress on the ironing board, helpless before the iron.”

Opposite: Tillie Olsen, 2005. Below: Olsen’s headstone. Right: Olsen and her husband, Jack, 1940s.

Photos Courtesy of Julie Olsen Edwards

In the late 1970s I traveled to Santa Cruz, California, to interview Olsen, an assignment from a women’s magazine which for a short time was hiring progressive, feminist editors. The interview was never published, but we talked for a full day. Her grace and intimacy subdued my intimidation as she showed me the many photographs of artists and writers displayed on her crowded book shelves, talked of her love for her daughters, her own history, of the injustice and sorrows of the world. We were then in the midst of the War in Vietnam, of the American struggle for Civil Rights, a time of horror and hope. When I think about that day in her living room, then sitting out on her lawn as we drank tea, I can still remember my walls breaking down from the force of her passion, and I listened and responded from that deepest part of me—the “farness, the selfness”—her words from Yonondio—for she talked about the “terrible importance” to the writer of encouragement, of recognition.

Break those words down to their literal meanings to comprehend the full force of her empathy—for she had known a lack of courage and thus the need for encouragement, especially from other writers, and she had known the enormous task of re-thinking— recognition—from a life centered on providing and caring for others to a life of writing, which often means putting oneself and one’s own needs first—contradictions to be experienced and explored but never to be erased. And she was concerned about our sons—though she had daughters—and how we raise them. Talking of a little boy she had read about: “You see the process here of this imaginative little boy having to become this tough avenging person—what happens is that he has to reject his mother and identify with his father—and it is an every-day pressure on him, the shaming, and sometimes actual brutality. How do you raise a certain kind of boy against this?” she asked me.

Speaking of the changes in conceptions of fatherhood we were immersed in then, she insisted, “what made the difference to a new kind of fatherhood even possible for some was the change from the six to the five-day working week, and the difference between an eight hour and a seven-hour day. Anyone who has worked seven instead of eight hours knows how much more of you is left over.”

In “Hey Sailor, What Ship,” the title an italicized elegiac retrain that is repeated throughout the story, she imagines a kind of righteous brotherhood: “Once an injury to one is an injury to all. Once, once, they had to live for each other.” At the close of the story is the dedication referring to the Spanish Civil War against fascism:

“For Jack Eggan, Seaman, 1915–1938.”

In “The Strike,” a piece of experimental journalism published in Partisan Review, a striker writes: “Forgive me that the words are feverish and blurred …but I write this on a battlefield.’ If feverish evokes passion, blurred suggests overlapping shades of color or meaning yet to be clearly distinguished. Tillie Olsen writes all her work from this battlefield, fighting injustice with stories and brilliantly honed insights, digging into layers of language—breaks and interruptions suggesting the deep divides and steep descents into thought and feeling not yet named but glimpsed, sensed, and if the “conditions” of creative work are present, at times able to be heard in the mind, or spoken aloud, then written onto the page.

Jane Lazarre’s most recent book is a memoir, The Communist and The Communist’s Daughter. She has recently completed a collection of poetry, Breaking Light.

This essay was written as an Introduction to the new edition of Tell Me A Riddle in Spanish by Las Afueras, Publishers. The English edition of Tell Me a Riddle is published by the University of Nebraska Press and includes an Introduction by Rebekah Edwards and a Biographical Sketch by Laurie Olsen and Julie Olsen Edwards.

- No Comments

November 5, 2019 by admin

Reclaiming Women’s Yiddish Writing •

In poems, essays, plays, novels, and every other genre known to literature, women wrote in Yiddish about love, family, politics, economics, class, sexuality, and the lure and dangers of the modern world. Perhaps the most surprising thing about this writing is how little of it is known today. In a downloadable lecture series, Professor Anita Norich of the University of Michigan examines Yiddish poetry and prose written by women, and discusses how these women claimed a place for themselves as modern Jewish writers. The four lectures by Norich, who is translator of the forthcoming Fun Lublin biz Nyu York, by Kadya Molodovsky, include more than five hours of video. Available from Yiddish Book Center.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...