Tag : memoir

October 23, 2020 by admin

“Like A Worm You Poke With A Stick”

In third grade, I wrote a short story about a girl who lost her mother in a fire. When a policeman finally reunites them, the girl says, “We meet at last.” A lifetime later, after many ups and downs between us, my mother and I also met at last. I was in my sixties, she in her eighties, when she said, “It’s love at second sight.” This chapter from my memoir, Losing the Atmosphere: A Baffling Disorder, A Search for Help, and the Therapist Who Understood, shows how our complicated relationship began.

Nona fed us lunch the same way every day. White kerchief tied over the coiled gray braid at the nape of her neck, small gold earrings bouncing gently, and lips sucked in over toothless gums, she carried a delicious-smelling pot from the stove to the table. She dipped in a spoon and loaded it with a flavorful mush of potatoes, meat, tomatoes, and string beans. Holding her

hand under it to catch any spills, she brought it toward my face. I opened my mouth and she slipped it in. While I chewed, she refilled the spoon and ferried it to my cousin Jerry’s mouth. Next was my cousin George’s. If food dripped down our chins, Nona scraped it upward with the spoon and guided it into our mouths.

All the while, she told us stories. “De farmer, he work hard to plant ta vegetables,” she would begin. “He put water and take out alla ta weeds.”

My turn for the spoon.

“He no see de horse what come in de night to eat ta vegetables.”

Jerry’s turn.

“An’ he tink to himself, Why alla ta vegetables dey disappear lak dat? What’s happen?”

George’s turn.

“An’ he say, I gawn fine out who take ta vegetables.”

The farmer hid in the field with his gun. There was a loud BAMMM! Nona always timed it perfectly. Just as the horse was running away, spinach dangling from his mouth, the pot would be empty.

After we got up to play, Nona walked to the sink, swaying from side to side on her bowed legs, and washed the pot and spoon. She stopped at the stove to lift the lids from the supper pots and give a quick stir. Then she took my baby brother, Marvin, out of his playpen. Carrying him in her arms, she went back down to the basement to sew.

I loved staying in my grandparents’ house, where we had been living for the past three months, since my father left for the war. During the day, my mother and aunts were at work, and Papoo peddled aprons and pillowcases to housewives in Brighton Beach. Nona, the lone adult at home, sewed aprons and took care of the children. Sometimes we played in the backyard, sometimes in the basement, where we crawled in and out of the empty cartons next to Nona’s sewing machine and Marvin’s playpen, or climbed up the mountain of fabric scraps and slid down.

Though not yet three, I sensed that the rules were looser here in Brooklyn. When my parents and I had lived in Knickerbocker Village on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, I hadn’t been allowed to put anything into my mouth if someone else’s mouth had touched it. Germs. There had been no stories at the table. Most of the mealtime talk had been Spanish practice—if I

wanted bread and butter, I had to say, “Quiero pan y mantequilla, por favor”—or my father reading aloud to my mother from the newspaper. And punishment at Nona’s wasn’t really punishment. Once, when Jerry and I did something we weren’t supposed to, Aunt Mollie said, “You naughty children!” but she was smiling.

I would find out years later that my mother also felt freer away from my father’s control. When she had brought me home from the hospital as a newborn, he’d forbidden her to use baby talk with me. No coo-cooing. She was permitted to speak English, but he spoke to me only in Spanish. To him, I was a grownup in miniature, one step away from the harsh realities of the job world, and it would be useful if I knew another language.

My father had also appointed himself the guardian of my health. Every evening, he demanded a report from my mother. It was chilly out; did you put a sweater on her? How much milk did she drink? When I caught my first cold at nine months, he berated her. She hadn’t dressed me properly, he said, hadn’t opened the window wide enough when she put me to sleep. My mother said she began to feel like hired help.

My parents met in March, 1941, at a foreign-language conversation club in Manhattan. Both were first-generation Americans whose parents—hers, Jews from Greece and Turkey; his, Jews from Russia—had come to America through Ellis Island early in the century. Bea, my mother, whose husband of three years had divorced her, was 26. A graduate of Brooklyn College, where she had majored in French, she came to the club because someone told her it was a good place to meet men. My father, Jack, 32 and also divorced—he’d gone to Reno to end a four-year marriage—was a regular who spoke several languages. He was self-taught, having dropped out of high school to support his younger brother and two sisters when both his parents died of cancer.

Sometimes I imagine their meeting. Jack saw a pretty, soft-spoken woman with long brown hair combed into a stylish upsweep. Bea saw a serious, handsome man with dark curly hair and a mustache over full lips. Chatting in French, they told each other where they worked: she, sewing in a garment factory, the only job she could get in the lingering Depression; he, at the post office, where he used his linguistic proficiency inspecting customs declarations.

Their three-month courtship included many strolls along the Coney Island boardwalk. Bea was captivated because Jack liked classical music, studied languages, and played chess, but mostly because he showed an interest in her. She told me her self-esteem had been badly damaged by her divorce, and also that she wanted to be married again to please her mother. The fifth of nine children—eight of whom lived to adulthood—she knew, as did all seven girls, that Mama wished the best for them. The best was a husband. When Jack proposed one May evening on a long walk from Coney Island back to her family’s home on 74th Street in the Bensonhurst section of Brooklyn, she accepted. They were married by a Justice of the Peace on July 4, 1941. I was born ten months later, on May 7, 1942.

A month or so after my birth, my mother told me, she arrived home from grocery shopping to find my father giving me a bath in the kitchen sink. To her horror, after he lifted me out of the basin of warm water, he filled it with cold and plunged me in. “Warm water opens her pores,” he explained over my shrieks. “If you don’t close them right away, she’ll get sick.” After that, my mother bathed me herself, when my father wasn’t home.

Another day, sometime during my first six months, my mother’s younger sister Sophia came to visit. According to the routine my father had established, my mother put me into my

crib after my evening feeding and closed the bedroom door. She and Sophia were about to leave for the movies when I let out a piercing howl. My mother started toward the bedroom. My father blocked her way.

“If you go in,” he said, “she’ll learn that all she has to do to get her way is cry.”

“You know I don’t usually go in,” my mother said as my wails continued, “but this isn’t her normal cry.”

“Don’t interfere! Go to the movies with your sister!”

They returned several hours later to find my father playing chess against himself in a silent apartment. The incident was never discussed.

When I was two and a half, my father began to worry about being drafted. Until then, he had been exempt from military service because of an enlarged heart. Now, with the war raging in Europe and the Pacific, the Selective Service was calling up men who had previously been deferred. Rather than wait for their letter, which would almost certainly have meant being sent into combat, he used his typing, stenography, and language skills to secure a civilian position in the Army. He was to ship out at the end of October, but when he said his wife was expecting a baby soon, Army officials allowed him to wait a few weeks.

My brother, Marvin, was born on November 10, 1944. A week later, my father sailed for Italy, and my mother, Marvin, and I moved into Nona and Papoo’s house. Its four apartments were already occupied, some by family, some by other tenants, so we added ourselves to Nona and Papoo’s apartment. With our arrival, its three bedrooms were crammed with ten people, including Aunt Mollie, whose husband was also in the war; her one-year-old son, my cousin Jerry; and my unmarried aunts, Rae, Sophia, and Diana.

In the beginning of my parents’ marriage, my mother had deposited her factory salary into their joint checking account, but after she made a small purchase without asking my father beforehand, he’d taken her name off the account. Now, with Nona caring for Marvin and me, my mother found a job as a substitute teacher at P.S. 128, a ten- minute walk away, and opened her own bank account. She also passed the Board of Ed test to become a permanent teacher and, in February, three months after our move to Brooklyn, was offered a fifth-grade class at P.S. 54 in Bedford-Stuyvesant, much farther away. She accepted, even though it meant she would get home more than an hour later.

At about the same time, Aunt Sarah and Uncle Sam, who also lived in the 74th Street house, told my mother about a vacant apartment around the corner, above a dry goods store on 20th Avenue. Though hesitant to move out on her own with two children, my mother liked the idea of having privacy and went to look at it. The small living room and bedroom faced the back. It was winter—no leaves on the trees—and she could see the fences and clotheslines in all the backyards of the houses on 74th Street, right down to Nona’s. She decided to take it.

I was miserable at my sudden banishment—from Nona, my aunts, my cousins. On 74th Street, if one grownup was busy, another was glad to pay attention to me. Here, there was just my mother, who was always busy. “I’ll look at it later,” she said if I tried to show her a drawing.

Every morning while she dressed Marvin, I dressed myself. Then I asked her to tie my shoelaces. “I’ll be happy when you learn to tie them yourself,” she would say in an annoyed voice. “Hold still!” After we dropped Marvin off at Nona’s, she and I walked to the JCH—Jewish Community House—on Bay Parkway, where she had enrolled me in nursery school.

My mother was rushed when she picked me up in the afternoon, too. “That’s lovely,” she would say, tucking my painting into her bag. “Now get your hat.” We walked the quarter mile

to Nona’s. Still in our coats, we hurried through the upstairs hall and down the side steps to the basement, where my mother lifted Marvin out of his playpen.

Back home, she peeled potatoes and cooked lamb chops and canned peas, washed the dishes, wrote lesson plans, cleaned the bathroom, and darned socks. She hardly smiled anymore. Marvin was too young to play with, so I amused myself, either indoors or on the sidewalk in front of the dry goods store owned by our landlady, Mrs. Feigenbaum. Sometimes I asked permission to walk around the corner to Nona’s. My mother usually said yes and might add, “Tell Nona I’ll be over in a half hour to use the washing machine.”

I was invariably cheerful at Nona’s, where I got lots of love and attention, but with my mother I began to whine.

“Mah-meee, I can’t find my sweeeater,” I complained one morning.

She stormed into the bedroom in her suit and her new short haircut that I was still getting used to—“I have no time for long hair,” she said soon after we moved—and pulled out all the dresser drawers. “Here!” She flung the sweater onto my cot. Feeling like a worm you poke with a stick, I put it on quickly so we could leave.

Spring came, and the two trees in Mrs. Feigenbaum’s back- yard burst into flowers that pushed against our windows like pink ruffles. “They’re cherry trees,” my mother said, smiling. She opened a window, glanced down to make sure Mrs. Feigenbaum wasn’t in the backyard, and leaned out over the clothesline to cut some branches.

“Aren’t they beautiful?” she asked.

I wasn’t sure she was talking to me, but I said yes just in case. In May, days before my third birthday, a package arrived for me from Europe. My mother and I opened it to find the smallest record I had ever seen.

“Hello, Viv. This is Daddy, talking to you from across the ocean in Italy.” The voice on the Victrola was scratchy, but unmistakably my father’s. “Do you remember how I used to lift you high in the air and say, ‘Uno, dos, tres, arreeeeeba’? And do you remember how you didn’t want to go to sleep when I put you back down in your crib, and you used to say, ‘No quiero dormir’?” I did remember.

Soon afterward, on a day my mother was particularly annoyed at me, I said, “Why don’t you pack me in a carton and mail me to Daddy?”

My mother smiled, then said, in her teacher voice, “That wouldn’t work, because when they sealed the carton, there wouldn’t be enough air for you to breathe. You can never send living things through the mail.” It made sense.

“Mah-meee, my legs hurt,” I whined as I trudged alongside her one day, holding the handlebar of Marvin’s stroller while we walked for what seemed like miles. To the dry cleaners on 75th Street. The grocery store on 73rd Street. The shoe store on Bay Parkway. “When are we going home?”

She stopped suddenly and slapped my face. “Get out of my sight, you fucking bastard! Go shit in your hat! Your name is mud!”

When she screamed like that at home, I went to my room to color until she was in a good mood again. How could I get out of her sight here, when I had to hold onto the stroller?

We kept walking, in silence now, looking straight ahead, so I couldn’t see her face. But our hands were holding the same handlebar. I felt her loathing seep through it and into me, circulating in my veins. For a minute, I felt like the worm you poke with a stick again. Then a picture came into my head of a silly man taking off his homburg, placing it upside down on the sidewalk like a pot, and squatting over it to have a bowel movement. I laughed out loud. A moment later, I stopped laughing and began sucking the thumb on my free hand. After that day, the picture of the squatting, shitting man came

to me whenever my mother screamed, “Go shit in your hat!” I always laughed, even when she slapped me.

It was as if I had two mommies: a love mommy and a hate mommy. The one who loved me hung my paintings on the wall. She let me lean against her when she read my Little Golden Books on her bed in the living room and gave me orange slices to suck when I was sick and threw up, to take away the bad taste. When the mommy who loved me was there, I didn’t know about the mommy who hated me, and when the mommy who hated me was there, I didn’t know about the mommy who loved me.

Finding it increasingly difficult to balance work and motherhood, my mother applied for maternity leave when the school year ended in June. The Board of Ed denied her request. Leave was for new mothers only, they said. Marvin was eight months old. Seeing no other option, she quit, even though the principal wanted her to stay and leaving meant she would lose her permanent license. Her plan was to look for a substitute job closer to home in September.

With the summer off, my mother was more relaxed and didn’t scream as much. Almost every day, she tucked a pail and shovel, a towel, and my bathing suit into the stroller alongside Marvin for the three-block walk to Seth Low Park. Often my cousin George came, too. My mother would read on a bench while we played in the sandbox or cooled off under the sprinkler in the wading pool. Sometimes I could even get her to push me on the swings.

She did find a substitute job in September, teaching English at Seth Low Junior High, and I went back to nursery school.

Then, in November, exactly a year after he had gone, my father wrote to say he was coming home from the war. His ship would be sailing into Newport News, Virginia, and from there

he would find a train or bus to New York.

We were all at Nona’s one afternoon when an upstairs tenant came rushing in and said, “I just saw your husband walking on Twentieth Avenue!”

“Go! Quick!” Nona urged my mother. “So you be there before him to say hello.”

Vivian Conan is a writer, librarian and IT business analyst who lives in Manhattan. Losing the Atmosphere: A Baffling Disorder, A Search for Help, and the Therapist Who Understood is her first book.

- No Comments

March 31, 2020 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

A Memoirist on Making Tragedy Meaningful

- No Comments

January 14, 2020 by admin

We All Stand Here Ironing

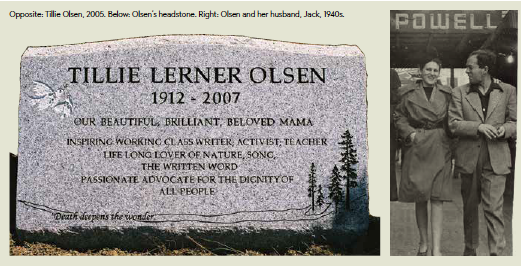

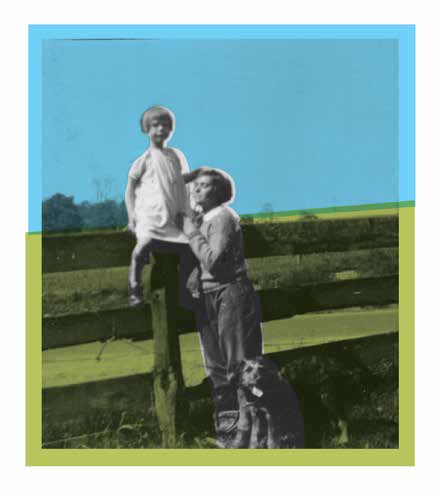

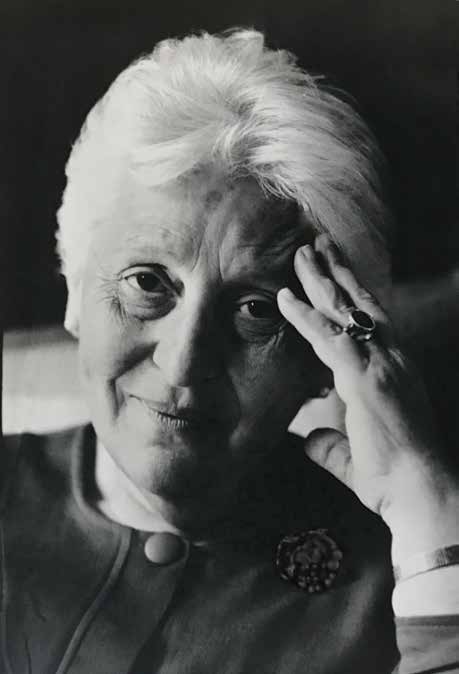

Tillie Olsen and her daughters, 1947. Photos Courtesy of Julie Olsen Edwards.

Tillie Olsen wrote her important stories and essays in a tradition of Jewish radicalism that insists on the struggle for economic, gender and racial justice as a burden and privilege of Jews—rooted in a history of oppression and survival, in the conviction that such experience demands empathy and activism. Devoting her writing and personal life to these values, Tillie Olsen was also the great writer of the experience of motherhood. In the unique, poetic prose of the stories, she plumbs the deepest layers of an experience that can combine overwhelming love with exhausting, demanding labor, devotion with anger, power with helplessness.

Olsen, among the most influential writers in American literature, certainly in my writing life, a maternal presence in her literary work and in a friendship that lasted from 1975 until she died in 2007. I want to claim her now not for myself, though including myself, not for the entire world, though she rightfully belongs to the multitudes, but especially for the people who struggle against injustice everywhere.

For Olsen, the conditions of our inner lives are inexorably interwoven with the material conditions of our lives in society. As she once wrote: “… not only the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, but the establishment of the means—the social, economic, cultural educational means to give pulsing, enabling life to those rights.”

In her writing and in her support for other writers, she joined the struggle.

In the great novella Tell Me A Riddle, Eva—a woman considered old then at 69—is about to die. To her husband, who for most of the story, names her out of his own contempt: “Mrs. Orator Without Breath,” “Mrs. Enlightened,” who asks bitterly, “You think you are still an orator of the 1905 revolution?” she responds: “To smash all the ghettos that divide us—not to go back, not to go back—this is to teach.”

Confined to a hospital bed with untreatable cancer, Eva is told by her daughter that a “man of God” came to her bed to comfort her. “The hospital makes up the list for them,” the daughter says, “and you are on the Jewish list.” But Eva, weak, yet still driven by her defining passion, shouts, “At once, make them go and change. Tell them to write: Race, human; Religion, none.”

Still she believed, her husband says near the end of the novella and in the last moments of her life. She may no longer be able to hear him when he finally calls her Eva, her name, and asks: Still you believed?

O Yes is her story of racial friendship and separation, a white child, a black child, friends until they reach a certain age and then, “how they sort…a foreboding of comprehension,” thinks the mother. The story was written long before Toni Morrison named an “Africanist presence” as a formal turning point in much white American literature, describing encounters between white and black characters in which a black character, “lubricates the turn of the plot and becomes the agency of moral choice.” Olsen may have sensed the nature of such moments when the young white daughter, unused to the powerful emotion expressed in a Black church they have gone to in support of her black friend, is overcome by conflicting feelings and faints. In adolescence, when the two girls have migrated to their separate worlds, the daughter cries to her mother, “Why do I have to care?” The mother caresses, trying to calm, but is thinking: “caring asks doing. It is a long baptism into the seas of humankind, my daughter. Better immersion than to live untouched.” Through the use of sentence fragments and specific cultural grammar, what Toni Morrison and James Baldwin accomplished in illuminating the poetry of Black English, Tillie Olsen has done for Yiddish syntax and inflection, forcing us to read language as more than communication formed over centuries of use but as poetry, for poetry must in part be understood as a way of finding in ordinary speech imagery and allusions that dive deep into consciousness. Words accompanying the 1994 Rea Award for Distinguished Contribution to the Short Story: ‘She [combined] the lyric intensity of an Emily Dickinson with the scope of a Balzac novel.’

In 1969, having given birth to my first child, I was seeking desperately, futilely I began to believe, for a work that would describe the sudden plunge into the deepest love I had ever known, but also the body-wide fear and paralyzing guilt that could obscure that love into periods of fog and confusion, into rages and weeping I neither recognized nor understood. Tillie Olsen gave me language to begin to name them.

In about 1975, soon after I had published my first book, The Mother Knot, a memoir about the transformational experience of giving birth and learning to mother, I received a gift from Tillie—a copy of her novel, Yonondio, From the Thirties. By then, I had read all her fiction with a wave of relief—like those enormous ocean waves at high tide which, though large, can be gentle if you are out far enough—your body sails over them, safe and amazed as you watch them crash into shore. So, reading her fiction, I was witnessing the crash—reading about the complex and powerful feelings in being a mother, far enough out not to be hurt, yet awestruck by the power of the wave. Tillie Olsen’s poetry and courage would enable me to participate in a sea of change over a lifetime of writing and teaching: the maternal voice, finally not trivialized or sentimentalized or falsified, not restricted to a “how to” or a pediatric manual mostly written by male doctors; instead, so truthful and eloquent she was driving this long-buried voice into literature.

In my now yellowed and fading paperback copy of Yonondio there was something I would learn lay at the very heart of her being. In the middle of the novel, she had inserted a note. In her characteristic tiny script, which I can hardly read today, stuck to the page with a nice red star (this was before post-its!), she crossed out a paragraph and, in the margins, wrote a note to me about how she would rewrite it. “Omit” she wrote, and added several question marks in dark black ink.

Tillie Olsen was born Tillie Lerner “in a tenant farm in Nebraska, the second of six children of Russian Jewish immigrants who left their homeland after involvement in the failed 1905 revolution. She grew up in Omaha, where her father worked as a painter and paperhanger and served as state secretary of the Nebraska Socialist Party. … In 1929 she embarked on what would be thirty years of low paying jobs (hotel maid, packinghouse worker, linen checker, waitress, laundry worker, factory worker, secretary).”

These words were written by two of her daughters, Julie Olsen Edwards and Laurie Olsen, significant because one of Tillie Olsen’s defining values was to pass on beliefs to the next generation—first to her own children, then to other writers in whose work she saw a sign of necessary voice, some in danger of being silenced by economic and political constraints. She spoke out for labor, against Apartheid and racism, against war, for women’s rights, for the protection of the earth. Like most dedicated activists, she could be fierce in her convictions, in her fury at injustice. But this was all very familiar to me. I had been raised in a family of Jewish American Communists, and this was one piece of our history, I think, that drew us together: we knew the faults of the old left— their righteousness, yes, and how wrong they were in some ways, but also the beauty of the core beliefs, the brilliant core always shining at the center of everything Olsen wrote.

Her essay, “Silences” (in a book by the same name), about the sources of literary silence through centuries of writing, is a sustaining work for every writer I know. She writes of the barriers to fullness of voice, constraints at times to coming to voice at all:

She quotes Herman Melville: “…the calm, the coolness, the silent grass-growing mood in which a man ought always to compose— that I fear, can seldom be mine. Dollars damn me—what I feel most moved to write, that is banned,—and it will not pay.” And she notes how Joseph Conrad described his creative process, unaware of the economic and gender privileges enabling him: “…I suppose I slept and ate the food put before me …but I was never aware of the even flow of daily life, made easy and noiseless for me by a silent, watchful, tireless affection.”

Photos Courtesy of Julie Olsen Edwards

Like Virginia Woolf imagining Judith Shakespeare, who as a woman could never have brought to life her genius supposing she possessed it like her actual brother, Olsen wrote of our great human loss—the lives that never came to writing, “among these, the mute inglorious Miltons: those whose waking hours are all struggle for existence; the barely educated; the illiterate; women.”

Olsen reminds us that for centuries women writers who created good and great work almost all never married, never had children, wrote under male pseudonyms— until the small trickle began in my generation, and now the whole earth begins to fill with women’s stories as some—more than before but still not enough—emerge into print.

I am seeing her now—we are walking through the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City—she is pointing out patterns in color and shape, the portraits that so compelled her; and always, no matter what I was writing at the time, she is asking me about my children—how are they, she wants to know—how old are they now? It was often my portrayal of mothers and children she commented on in my work, the complicated layers of motherhood, the “amplitude” she called it.

It was her own amplitude that enabled many writers of my generation to begin to heal the split between our writing/artist selves and ourselves as mothers, and in imagining that healing begin to glimpse the nature of the disease that had split us, turning being an artist and a mother into inherent contradictions. She never minimized the effort, knowing the battles that accompany such a desire, and she wrote the history for us, let us know by her own honesty and specificity that we were not alone. But “Nobody,” she told me during one conversation about motherhood, “has a harder time in our society than a mother who is trying to make it alone.”

Olsen had a husband, Jack Olsen, a union organizer, waterfront worker and educator with whom she raised her four daughters and shared her life until he died, but her first work wasn’t written until her children were finally in school. She still worked a daily job, so it is not disembodied imagination nor an accident of inspiration that the first line of her first published work is “I stand here ironing.”

A mother, overworked and suffering feelings of guilt toward her daughter who is having trouble in school, the eldest, the one who she depends on to help care for the others—the story ends with the final lines so many of us know by heart: “ So all that is in her will not bloom—but in how many does it? There is still enough to live by. Only help her to know—help make it so there is cause for her to know—that she is more than this dress on the ironing board, helpless before the iron.”

Opposite: Tillie Olsen, 2005. Below: Olsen’s headstone. Right: Olsen and her husband, Jack, 1940s.

Photos Courtesy of Julie Olsen Edwards

In the late 1970s I traveled to Santa Cruz, California, to interview Olsen, an assignment from a women’s magazine which for a short time was hiring progressive, feminist editors. The interview was never published, but we talked for a full day. Her grace and intimacy subdued my intimidation as she showed me the many photographs of artists and writers displayed on her crowded book shelves, talked of her love for her daughters, her own history, of the injustice and sorrows of the world. We were then in the midst of the War in Vietnam, of the American struggle for Civil Rights, a time of horror and hope. When I think about that day in her living room, then sitting out on her lawn as we drank tea, I can still remember my walls breaking down from the force of her passion, and I listened and responded from that deepest part of me—the “farness, the selfness”—her words from Yonondio—for she talked about the “terrible importance” to the writer of encouragement, of recognition.

Break those words down to their literal meanings to comprehend the full force of her empathy—for she had known a lack of courage and thus the need for encouragement, especially from other writers, and she had known the enormous task of re-thinking— recognition—from a life centered on providing and caring for others to a life of writing, which often means putting oneself and one’s own needs first—contradictions to be experienced and explored but never to be erased. And she was concerned about our sons—though she had daughters—and how we raise them. Talking of a little boy she had read about: “You see the process here of this imaginative little boy having to become this tough avenging person—what happens is that he has to reject his mother and identify with his father—and it is an every-day pressure on him, the shaming, and sometimes actual brutality. How do you raise a certain kind of boy against this?” she asked me.

Speaking of the changes in conceptions of fatherhood we were immersed in then, she insisted, “what made the difference to a new kind of fatherhood even possible for some was the change from the six to the five-day working week, and the difference between an eight hour and a seven-hour day. Anyone who has worked seven instead of eight hours knows how much more of you is left over.”

In “Hey Sailor, What Ship,” the title an italicized elegiac retrain that is repeated throughout the story, she imagines a kind of righteous brotherhood: “Once an injury to one is an injury to all. Once, once, they had to live for each other.” At the close of the story is the dedication referring to the Spanish Civil War against fascism:

“For Jack Eggan, Seaman, 1915–1938.”

In “The Strike,” a piece of experimental journalism published in Partisan Review, a striker writes: “Forgive me that the words are feverish and blurred …but I write this on a battlefield.’ If feverish evokes passion, blurred suggests overlapping shades of color or meaning yet to be clearly distinguished. Tillie Olsen writes all her work from this battlefield, fighting injustice with stories and brilliantly honed insights, digging into layers of language—breaks and interruptions suggesting the deep divides and steep descents into thought and feeling not yet named but glimpsed, sensed, and if the “conditions” of creative work are present, at times able to be heard in the mind, or spoken aloud, then written onto the page.

Jane Lazarre’s most recent book is a memoir, The Communist and The Communist’s Daughter. She has recently completed a collection of poetry, Breaking Light.

This essay was written as an Introduction to the new edition of Tell Me A Riddle in Spanish by Las Afueras, Publishers. The English edition of Tell Me a Riddle is published by the University of Nebraska Press and includes an Introduction by Rebekah Edwards and a Biographical Sketch by Laurie Olsen and Julie Olsen Edwards.

- No Comments

April 2, 2019 by admin

“In Vain, My Attempts to Be Reasonable”

Courtesy of the Matilda Robbins Papers

“I WAS 29 YEARS OLD when I decided to have a child.”

Radical firebrand Matilda Rabinowitz had already led an extraordinary life by age 29. She was an elected Socialist Party leader, an IWW [International Workers of the World] organizer; a key figure in a textile mill strike in 1912.

Taube Gitel Rabinowitz, a Russian-Jewish immigrant, arrived in America in 1900, age 13, with minimal education and no money. With self-confidence and grit, she transformed herself into Matilda Gertrude Robbins, a liberated, politically engaged woman. Her trajectory was tied to the turbulent times she lived in. But when it came time to balance her work—bringing about revolution—with starting a family, the obstacles Robbins faced will be familiar to any woman today. Yes, even our socialist foremothers struggled to have it all.

We know about her daily struggles thanks in part to Robbins’s newly published memoir, Immigrant Girl, Radical Woman: a Memoir from the Early Twentieth Century (Cornell ILR Press, 29.95). Echoing up through the years, her words shed light on so many problems we still see: the tensions between the time it takes to pursue meaningful work outside the home while being a caretaker, the casual indifference of male revolutionaries to the plight of their female comrades, and the feminist movement’s alienation from any class struggle.

Robbins was caught at the intersection of class oppression and gender oppression; her lively description of what this looked like can be a guidepost for today’s left, as so many feminists and progressives alike have been reinvigorated in pushing for policies that uplift women, like expanded free childcare, an increased minimum wage, and—especially—universal health care.

Just before Robbins turned 30, she underwent a change: “There came over me a strange mood, an overwhelming, unconquerable desire to have a child. In vain my theories about economic insecurity, in vain my attempts to be reasonable,” she wrote in an unpublished article from 1927, “The Life of a Wage-Earning Mother.”

Today we would say that her biological alarm clock went off. When Matilda decided to have a child in 1919, she was unmarried. The father of her baby was a fellow IWW activist and, it’s safe to say, a young man of poor judgment. Ben Legere would eventually have four wives and many children, none of whom he did much to support. Robbins knew Legere would not support her emotionally or financially, and in fact it was Robbins who often supported the feckless Legere, paying his rent so he could pursue his acting career. (The IWW supported dramatic projects as part of their work so his dramatic career was within the IWW world.) At times she even took care of his children by other women.

It didn’t matter. Robbins was, for reasons hard to understand, addicted to Ben and the drama of their on-again, off-again relationship. What’s more, both Robbins and Ben were invested in the Free Love ethos of the time (another famous adherent: Emma Goldman), which saw relationships as something men and women should be able to enter, and dissolve, on their own, without interference of the state. This tended to work out better for the men than for the women.

Once she gave birth, Robbins describes the child-care choices in her own neighborhood as “ill-kept charity holes” and complains of the way they treated the mothers compelled to leave their children there. At the same time, “I tried an uptown Montessori kindergarten… with cultured, smiling ladies in charge, and I found that it was only for the rich….” At another kindergarten, the registrar “felt very uncomfortable over the fact that I had no husband.” The shame and frustration Matilda experienced as a working mother 100 years ago feels appallingly familiar. “There are books a-plenty and educators and exponents of ‘new’ and ‘modern’ theories on child culture…. But what is there for the mother compelled to leave her child for the job?” Robbins asked. Good question.

A century later little has changed. For instance, the fertility discourse in the Jewish community has been dominated for decades by men loudly lamenting low birth rates while staying silent on the systemic child-care burdens’ falling on women. The list goes on: the United States is the only developed country in the world to not offer federally mandated paid maternity leave. In many states the annual cost of childcare can be as much as a year’s tuition at a public university. Mothers are criminalized for leaving their children at a playground while they themselves interview for jobs. The safety net is full of holes.

BUT ROBBINS’S AMBITION WOULDN’T BE STYMIED BY HER CIRCUMSTANCES; like many working mothers today, she worked around and through her troubles. Though her path wasn’t easy (she sometimes had to pretend to be divorced rather than an unmarried mother), Robbins remained politically engaged as a secretary for the Socialist Party, taking a front row seat at the Sacco and Vanzetti trial in the early 1920s. And she remained proud of her choice and certain that the concerns of working mothers were as important as those of any other laborer. Indeed, the quotes above come from that 1927 article she drafted about choosing single motherhood, “From The Life of A Wage Earning Mother.”

Her progressive comrades, however, didn’t find single motherhood such a compelling topic. The article was rejected by The Nation in 1927 (and by Redbook in 1977). The sad thing, of course, is that the issues Robbins raised—low wages, dire lack of affordable childcare, patronizing and cruel treatment of single working mothers—remain relevant. One could see Redbook or The Nation being eager to publish her account today.

“From The Life of A Wage Earning Mother” is included as an appendix in Robbins’s memoir, which is illustrated with vibrant woodcuts by her granddaughter, artist Robbin Legere Henderson. Henderson also included clarifying historical material as well as reflections on her grandmother’s fascinating life, pointing out and filling in the gaps in Matilda’s story. As Legere Henderson notes, Robbins’s writing can be frustratingly circumspect. It appears that Ben Legere was, at best, a neglectful partner and at worst abusive. What exactly kept drawing Matilda back to him? We never really find out. Matilda’s relationship with IWW counsel Fred Moore, one of the lead attorneys during the Sacco and Vanzetti trial, is also left ambiguous, though her granddaughter believes that they were lovers. At one point in the memoir Matilda claims that though she never lacked for male attention, “[c]asual sex affairs had no appeal for me.” A woman of fierce principle, perhaps Matilda saw the need for a comfortable love life as a weakness, unbefitting a committed revolutionary.

This is one of the many ways Robbins’s life was defined by her iconoclasm. She was a single mother by choice at a time when such a thing barely existed. Perhaps most notably, she was an East Coast, Russian-Jewish immigrant woman in the IWW , a masculinist union movement centered in the West and dominated by members in heavy industry like mining, ship building, and logging. Though we think of the history of American labor as well-populated by Jews, Jewish involvement in the IWW was comparatively tiny. In the popular imagination, the IWW was associated with hobos, and with good reason. Hobos were itinerant, male manual laborers, the emblematic IWW member. In 1912 the Socialist Party candidate for President was an IWW member named Eugene V. Debs. He got almost a million votes, and thus the IWW vision of a workers’ revolution didn’t seem too farfetched, or unreasonable.

Perhaps that explains why the fervor—and success—of the IWW was a perfect home for Robbins’s energy. The IWW stood apart from other labor movements of its day. Instead of organizing along craft or guild lines, it organized skilled and unskilled workers together, by industry. Rather than working for reform, the IWW ’s goal was to seize control of the factories themselves, bringing about an industrial revolution by the workers. The IWW made no distinctions along gender, racial or ethnic lines. Instead of top-down administration, the IWW believed that power resided with the workers. Anyone could be a leader, a philosophy that was understandably attractive to a woman like Robbins.

When the IWW began to organize women, mostly immigrants, in textile mills, opportunity knocked for Robbins, sent in 1912 to organize her first strike, in Little Falls, New York. Though Little Falls was much smaller in scale than the Lawrence and Lowell textile strikes in Massachusetts, it was still significant, and for her help winning the 14-week strike she earned a place in American labor history.

Robbins understood intrinsically why factory conditions had to change. Her first job was at 14, in a shirtwaist factory in New York. Too young to work there legally, she was hidden in a hamper of shirtwaists when the inspectors came around. In 1911 the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire demonstrated just how deadly unchecked industrial capitalism could be for workers.

ALONG WITH HER LACK OF REFLECTION ON HER LOVE LIFE, Robbins’s memoir is curiously silent on her Jewishness, aside from the grim description of her early years in the Pale of Settlement. Legere Henderson says that while her grandmother did occasionally speak Russian, she never heard her speak a word of Yiddish. After the establishment of the State of Israel Matilda became an unaffiliated anti-Zionist. It’s certainly possible that, like many other Eastern European immigrants, she wished to create a new American life, unshackled to the old fashioned strictures of Jewishness. Her position was also likely due to the influence of the IWW , which de-emphasized differences like race and ethnicity in favor of a universalism of the proletariat. We know from her memoir that Matilda had many Jewish friends and traveled in very Jewish circles, but she never seems to participate as a Jew. Class identity seemed always to determine Robbins’s understanding of the world around her.

That emphasis on class consciousness left Robbins with blind spots. IWW values included and intertwined with destigmatized birth control, free love and free speech. But at its core it remained a masculinist movement and articulated no specific vision for the emancipation of women workers. Incredible though it seems today, women’s suffrage was entirely absent from the IWW agenda, and Matilda never mentions this as a concern, even though the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920, at the height of her activism. Indeed, though Matilda doesn’t say as much in her memoir, IWW women were encouraged to see middle-class female activists not as allies, but as adversaries, women working to hold up a fundamentally rotten system. In her memoir, Robbins never connects her own experiences as a working mother with the oppression of systemic sexism, nor does she suggest political solutions.

What Robbins doesn’t say in “From The Life of A Wage Earning Mother” is made explicit in her memoir: despite the systemic inequities, what made single motherhood possible for her was her extensive network of friends, especially her close friendships with bohemian and middle-class feminists. They were the ones who provided the emotional and financial support she needed at key moments. They believed in her and pushed her to further her education and career. Her closest friend was Marie Hourwich, also a Russian Jewish immigrant. Despite their common background, Hourwich came from an upper-middle-class family and had graduated from Johns Hopkins. Robbins had an eighth grade education. When they met in 1911 in Boston, Hourwich was working as a statistician with the Massachusetts Minimum Wage Commission. She and a number of other young college-educated women had come there for a project to survey the women of Boston about working conditions.

Matilda Robbins impressed Hourwich and her friends with her command of foreign languages, her unaccented English (Marie Hourwich still had a heavy Russian accent), and her reading habits. Robbins quickly went from working in a shirtwaist shop to being Marie’s assistant. Though she was enormously fond of Hourwich, Robbins was very aware of their class differences. She dryly describes herself as an “untutored immigrant girl” who nonetheless spoke a refined English and had a command of economics and labor. Next to these New England college girls, Robbins says she was “a creature of another world.” Though she would always be aware of the difference in privilege, Robbins was eager to be in Hourwich’s world, and they became lifelong friends.

Robbins’s friendship with another statistician, Marie Kasten, inspired her to go to college. Kasten convinced her that, with her aid, she would be able to enroll in her alma mater, the University of Wisconsin at Madison. Robbins had set about saving money for the necessary remedial tutoring when life intervened. Just as she began her plan to ready herself for college, she got the call to go to Little Falls and lead the strike there. Though she never did go to college, Robbins maintained her friendships with middle class feminists the rest of her life and often relied on them for support.

This is the most poignant message of Immigrant Girl. Revolutions are begun in unwavering commitment to principle. Real political change, on the other hand, is an endless grind of compromise. Indeed, human relationships in general are built on compromise, and the constant negotiation of conflicting identities. No one, not even revolutionaries, can live without friends.

Rokhl Kafrissen is a journalist and playwright in New York City. Her work on new Yiddish culture, feminism, and contemporary Jewish life has appeared in Haaretz, The Jewish Week, The Forward, Alma and Lilith. She conducts the biweekly “Rokhl’s Golden City” column for Tablet, on Yiddish and Ashkenazi life in all its incarnations.

- 1 Comment

April 2, 2019 by admin

The Matron Saint of Israeli Feminism

Photo: Joan Roth

Reading Alice Shalvi: Never a Native was like discovering a kindred spirit. From the moment I first picked it up, I carted the heavy hardbound volume around with me everywhere, stealing glances at the cover photograph of kindly, white-haired Alice smiling pensively back at me—in synagogue, where I read her book behind the mehitza; in the classroom, where I tore through a few more pages while my Talmud students learned in hevruta; and in the theater where I’d taken my children to see a play, my cell phone flashlight illuminating the page. “Ah yes, I know where you are, I have been there too,” Shalvi seemed to be saying to me wherever I toted her around.

Shalvi, whose memoir (Halban Press, $18.99) was published just before her 92nd birthday, knew the synagogues and study houses and theaters of Jerusalem intimately, though she too, as she avows, was never a native. Alice Margulies was born in 1926 in Essen, Germany, and fled to London with her parents and older brother eight years later. Shalvi had already taught herself to read in her native German by age four, and she quickly taught herself English as well so she could devour the novels of Lewis Carroll, Louisa May Alcott, E. Nesbit, and Arthur Ransome. In her primary school she was frequently asked by her teachers to entertain the class by reading aloud while the other pupils learned to sew, a skill she consequently never acquired. (And here I flipped to the front cover and smiled back at Alice, because I shared her predicament—I never learned to sew or drive or acquire any practical life skills because I was always the designated reader in the family.)

During the war, Shalvi’s family moved to a village in Buckinghamshire. When she was not performing in school plays, singing in the choir, or reading books from the lending library, she rode around the corn fields on a bicycle, learned to play tennis and cricket, and discovered British Romantic poetry: “One spring day, turning a bend, I found myself, unprepared, confronting a vast bank of daffodils. I had never before seen such an abundance of what appeared like wild flowers thronging an open space.” Years later, in Jerusalem, teaching Wordsworth’s poem about stumbling upon a field of daffodils, she was astonished to discover that her students had never heard of a daffodil. Five years ago, when substituting for my husband in the English department at Bar Ilan University, I taught this same poem and had the same experience. Like Shalvi, “only then was I made aware of the absence of this quintessentially English flower from the abundant flora of the holy land.”

Shalvi and a friend bribed a teacher with cigarettes to teach them Latin so that they could take the entry exams for Oxford and Cambridge. She was accepted to Newnham, then one of two women’s colleges at Cambridge, where she and her fellow students were expected to live cloistered lives: sex was considered “obscene, indecent, smutty,” and women had to sign out if they left the college after 8pm. Reading about Alice’s adventures in Cambridge, I am grateful that I attended this university over a half a century later, though I identified with many of her experiences: I too hung a photograph of the Kotel on my dorm room wall; I too suffered from an inadequate number of toilets (mine was across two courtyards, though fortunately my baths were not limited to a shallow five inches of water, the depth designated by a black line on the tub); I too attended Friday night dinners at the Jewish Society on Thompson’s Lane, where at the Sabbath meal (by my time, alas, this license had been revoked). As the only religious Jew in my English program, I had many experiences similar to Alice, who relates that she tried to explain the concept of simile to her classmates by citing the prayer in which the children of Israel’s relationship to God is compared to “clay in the hands of a potter”; she was dismayed to discover that few of her classmates had ever heard of this prayer. At Cambridge I also found that many of my frames of reference were foreign to my classmates, which rendered my experience there all the more lonely.

After Aliyah…

It was at Cambridge that Shalvi first became aware of the horrors of the Holocaust and the fate of her father’s brother’s family, all of whom were shot to death in their native Poland. “Worst of all and hardest to come to grips with, even today, was my growing awareness of a startling paradox: while the extermination of European Jewry was in progress, I was enjoying what were undoubtedly the happiest years of my adolescence, safe and secure amidst the natural beauties of rural England.” A Zionist from her early childhood, when she’d danced the hora around her family’s kitchen table, Shalvi resolved to move to Palestine: “I made the fateful decision to go there as a social worker, rehabilitate people like these youngsters, and assist them in becoming useful, committed citizens, fellow builders of a new Jewish state that, together, we would help bring into existence.” She went on her first visit to Palestine during Christmas vacation of 1947, less than a month after the U.N. vote on the partition plan but before the British withdrawal. The euphoria was evident, particularly in Tel Aviv, where “houses were shooting up, sparkling white in the bright Mediterranean sunshine that heightened the blue of the ocean with an intensity never seen in England. I’d not expected the sun to be so blinding, the sky so cerulean, the sea so calm.”

After studying social work at the London School of Economics (L.S.E.), Shalvi made aliyah, settling in Jerusalem in November 1949. She recalls a period when everyone walked around confused, unsure whether the street they were on was called Queen Melisanda or Heleni Ha-Malka. In neighborhoods like Talbiye, Katamon, and Baka—where I live now, with all modern conveniences— the streets had no names, the houses had had only plot numbers, and no one had telephones at home. In her first year in the country, she was seduced by her landlord who forced her to sleep with him when his pregnant wife was out of the house; “today,” she writes, “we’d call it rape.” Shalvi describes several men she dated as a young single woman in Jerusalem, though she never explains how she overcame the sense of unattractiveness that haunted her as a child: “My bust was too small, my hips too broad. Even had my mirror not reflected the reality… many wounding comments on my appearance… combined to instil in me both an overwhelming sense of my own inadequacy and a comparable need to compensate. Such compensation might be accomplished by academic achievement.” Surely her academic achievement was responsible for some of her confidence, but it is still hard to understand where she mustered the courage to pursue and then propose marriage to the handsome young American banker named Moshe whom she fell in love with when she first sighted him at a party for the Hebrew University. The couple set off to Paris on their honeymoon, where they bought baguettes and cheap plates and cutlery so that they could eat in their hotel room, since Moshe kept strictly kosher. “It was our first experience of keeping house together. We made abundant and blissful use of the big brass bed. We were inordinately happy. The week in Paris proved an auspicious beginning to over 60 years of compatibility and compassionate companionship.” Moshe took pride in Shalvi’s professional accomplishments and always encouraged her to excel, never feeling threatened by her achievements. He was, in every sense, just as feminist as she.

Shalvi became pregnant soon after their marriage, and she went on to have six children in 15 years: “My conception of a happy family was undoubtedly inspired by the numerous books I read that portrayed the adventures of siblings engaged in a series of fascinating activities… I envied these fictional families and perhaps unconsciously longed to replicate them in my own adulthood.” Her first pregnancy in 1951 was during a period of rationing, when pregnant women were allocated two fresh eggs a week, but she felt happy and healthy. On a visit to London she bought a book about natural childbirth and taught herself its precepts, shocking the doctors when she refused medication during labor: “It seems I was Israel’s pioneer of natural childbirth,” she muses. Her labor pangs began during an English department study session at her apartment, where members of the faculty were gathered to read Blake, and throughout her children’s early years, she and her husband remained intensely engaged in their respective professions.

Shalvi’s reflections on working motherhood are brave, candid, and—surely not just for me—deeply inspiring. She acknowledges that she was not present for her children nearly as much as they needed or wanted her to be, but she is proud of the people her children became: “I was not a source of the loving individual attention every child desires and needs. Frustrated, they sought other sources of attention and affection—friends, lovers, and eventually spouses. Today my children reproach me for my neglect but I take a certain degree of (cold) comfort in the fact that they’ve learnt from their own negative experience and that they, in contrast to me, are not only model parents but equally dedicated grandparents.” How refreshing that Shalvi can write so openly about her inadequacies as a mother, while also appreciating decisions that leave us feeling most uneasy can prove surprisingly salutary.

In one of the more private and painful moments in this memoir, Shalvi reflects on an illegal abortion she underwent in 1950s Jerusalem. She became pregnant while her older children had mumps, and her doctor informed her she had to terminate the pregnancy because infection with mumps could result in brain damage in the embryo. Shalvi reluctantly and ambivalently consented. She continues to be plagued by what she underwent in the back room of the doctor’s house: “I never told Moshe about the abortion. I fact, I told nobody. I have never spoken of it. Yet similarly, I have never forgotten it. Though I gave birth with my customary ease to three additional blessedly healthy, carefully planned, children, the thought of that unborn child still plagues me. Was it a girl or a boy? Fair-haired like Micha or dark like Ditza? As placid as Hephziba or wild, like Benzi? And would it indeed have been in some way abnormal, or might it, despite our fears, have proved no less healthy than its siblings? The questions can never be answered; the regret and guilt never fully assuaged.” Decades later Shalvi would go on to fight for increased awareness of women’s medical and psychological needs.

Gender Inequality, First-Hand

Shalvi learned her compassion and her concern for others from her own life experiences. When she birthed her first son, her roommate in the maternity ward of the Anglican school where Hadassah Hospital was then housed was a gaunt Kurdish woman who had just given birth to her seventh child, and had no visitors. The woman lay there miserable as all the members of the English department took their turns visiting and congratulating Alice on the birth of her firstborn: “I learned a great deal through this pathetic woman and her experience, of the overriding importance in some cultures of bearing sons, of the lowly status of females…of the contempt in which new immigrants from the Arab countries were held by the European veterans.” Shalvi went on to become instrumental in founding a “Women’s Kitchen” in a poor neighborhood in Katamon, a clubhouse for women immigrants from Arab lands.

Though she had made aliyah with a degree in social work, Shalvi was unable to find work in her field. Instead she landed a job teaching in the English department at Hebrew University; among her students were the young Yehuda Amichai, Dan Pagis, and Dahlia Ravikovitch, who became some of Israel’s most famous and celebrated poets. Nearly two decades later, when her youngest child was a toddler, she accepted an offer to found the English Department at Ben Gurion University. Four years later, the position of university dean became vacant. “Few of the men (needless to say they were all men) whose names were mentioned [as candidates] had what I considered the necessary qualifications.” And so Shalvi submitted her candidacy. Here, as throughout this memoir, Shalvi does not come across as arrogant or brash. On the contrary, she had a realistic sense of her own abilities and a supportive husband always at her back, and she was undaunted by the possibility of failure. “But you’re a woman!” she was told by the humanities dean. “You should be ashamed of yourself,” said the incumbent she hoped to replace. She was accused of “blatant lobbying” and “shameless self-promotion,” and she did not get the job. But for Shalvi, each failure, like each success, was a learning opportunity. “My humiliating experience led to a profound change in my perception of gender equality in Israel.”

Shalvi went on to devote herself tirelessly to advancing the status of women in all sectors of Israeli society throughout the 1980s and 1990s. She served on the Namir Commission to propose legislation and administrative changes designed to improve the social, economic, and political status of women. She worked with religious feminists to campaign on behalf of agunot, women whose husbands were missing, and mesuravot get, women refused divorce. She was instrumental in founding the Israel Women’s Network, a non-partisan organization to advance women’s status. She organized an international conference of women writers in 1986 to raise the self-esteem of Israeli women authors, hosting such luminaries as Grace Paley and Marilyn French. She persuaded the head of television at the Israel Broadcasting Authority to begin designing programs for women, of which there were none. She spoke on panels with Palestinian women, searching for common ground. She was involved in a six-month in-depth investigation of human trafficking and forced prostitution. She helped raise awareness about women’s health issues, founding an information hotline that referred women to sensitive and sympathetic doctors. Just recently, when I called the national hotline of my health clinic and listened to the menu of dialing option, I was told for the first time that I could press “5” if I wanted to speak to a doctor or nurse about pregnancy or childbirth; I have no doubt that Alice Shalvi is responsible, albeit indirectly, for this development.

Educational Excellence for Religious Girls

And yet in spite of all her work on the national level, in Jerusalem Shalvi is perhaps best known for her tenure as principal of Pelech, a high school founded in the 1960s for ultra-Orthodox girls. From its earliest days, Talmud was part of the compulsory curriculum at Pelech; a rarity for girls’ schools at the time. (The name of the school means spindle, and is spoken derogatorily by a misogynist sage in the Talmud who contends that “Women’s wisdom is solely in the spindle.”) Shalvi first became involved in Pelech as a parent—her eldest daughter Ditza, who was unhappy in her Orthodox high school, asked her parents to transfer to the Pelech High School for Haredi Girls, as it was then known. Uneasy with the idea of sending her daughter to such a religious school, Alice climbed up Mount Zion—where the school was then housed—to check it out. She engaged one of the students in conversation, and discovered that this ultra-Orthodox girl was working on a paper on Christian symbols in the novels of Graham Green. “Christian? Graham Green? At a haredi school? This openness was beyond belief. After that I had no objections to Ditza transferring to Pelech.”

In 1974, when Ditza was still enrolled, the founders of the school announced their intention to close it down—they were uncomfortable with the “infiltration” of modern Orthodox families. One day shortly thereafter, during a visit from the Ministry of Education, the principal was asked whom the ministry should be in future contact with on matters regarding the school. Without a moment’s pause, the principal told him to be in touch with Professor Shalvi—and thus to her total surprise, Shalvi became the school’s new principal. Though the school was already catering to a more enlightened demographic, Shalvi found that her religious progressivism was often at odds with the school’s ethos; in her new role, she had to put away her elegant pantsuits and instead wear long skirts, though she was never able to bring herself to cover her hair, as many traditional Orthodox women do. When she tried to advocate for replicating the American bat mitzvah program she had witnessed on a recent trip, one of the male Jewish studies teachers caustically replied, “In an orchestra, when the violinist plays the notes composed for the violin and the trumpeter plays the notes composed for the trumpets, there is harmony. But when the violins play the trumpets’ notes and the trumpets play the notes of the violinists there is discord.” Chastened, Shalvi writes that she “learned never again to express my heretical views on the inferior status of women within the confines of Pelech.”

Even so, Shalvi continued to push the envelope in her role as principal—she hired an American woman with an expertise in Talmud to teach a course on women and Jewish law, and she brought in a commanding officer from the Israel Defense Forces to speak to her students about women’s service in the military. Ultimately, her heresy became too much for the school officials to bear, and she felt she had no choice but to resign so that the school would not lose its accreditation. Still, Shalvi remains inordinately proud of “my girls,” as she refers to her Pelech graduates, one of whom is now her own rabbi. “Surveying how feminism has affected Israeli society, one is compelled to admit that the greatest revolution has occurred in Modern Orthodoxy,” she contends. “Not only have the women themselves ‘come a long way’; they have carried their communities in their wake.”

Shalvi, who was the subject of Paula Weiman-Kelman’s documentary “Rites of Passage,” which aired recently on ABC, was tireless and tenacious in her professional and public roles. In 1990, when she was settling down for what she thought would be a quiet retirement, she was asked to head the Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies, which offered rabbinical training and advanced degrees in Jewish studies. Shalvi agreed and became rector and then president, a decision she later regretted: “The double burden was too heavy for one person to bear, and as I soon learned, I was totally ignorant as to the complexities of the Conservative movement in the U.S.” Even so, she acknowledges that she has “nothing but happy memories” of her days at Schechter, where she founded Nashim, an academic journal of Jewish feminist studies, and she helped create the Center for Women in Jewish Law.

Reading this memoir, I was struck by the enormous debt of gratitude that I, as a woman in Jerusalem, owe to Shalvi’s trailblazing. When Shalvi pushed for a bat mitzvah program at Pelech, such an idea was unheard of; there is no question that my daughters and their contemporaries will have bat mitzvah ceremonies. When I was pregnant, I had my pick of Lamaze classes to attend (though it was still difficult, in the early 2000s, to find a woman obstetrician/gynecologist). When I wanted to study Talmud on a high level, there was a host of institutions to choose from—some for women only, and some co-educational. And when I wrote a book about my experiences studying Talmud as a woman, the opening chapter was first published in Nashim, the journal Shalvi founded.

Feminism among religious women in Jerusalem is a funny thing; just recently, I offered a copy of Lilith magazine to a religiously observant friend my age who swims with me at the pool in the mornings after dropping off her children at school. “A feminist magazine?” she looked at me quizzically. “Sorry, that’s not for me. I’m no feminist,” she said, before heading out to teach history at the university. I wanted to call after her, “You’re not a feminist? How did you get to where you are, if not for the feminists? Why do you think you have childcare for your toddler? Why are you able to work as a mother? How did you get your maternity leave? What kind of historian are you?” But I knew my protests would fall on deaf ears. Her response is a reminder that we still have a long way to go. Alice Shalvi, having completed the memoir she began two decades ago, has taught herself to meditate and seems finally to have found tranquility: “No words are needed. No words suffice. Just as two lovers sit side by side in silence, each absorbing each other’s presence, so I sit absorbing and at the same time surrendering myself to the Divine Spirit.” There is more work to be done, but the mantle has been passed to my generation, and to my children. We are so fortunate to have Shalvi as our model, our mentor, our guiding light.

Ilana Kurshan’s own memoir, If All the Seas Were Ink, won the 2018 Sami Rohr Prize in Jewish Literature.

- No Comments

October 15, 2018 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

The Depth of Grandparents’ Love

Lilith’s Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough spoke to memoirist and novelist Kathryn Harrison about her latest foray into family history, On Sunset.

Lilith’s Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough spoke to memoirist and novelist Kathryn Harrison about her latest foray into family history, On Sunset.

“Blending family history and mythology, anecdotes and photographs, this book is not simply one woman’s open love letter to two magnificently eccentric grandparents; it is also a testament to the enduring power of memory,” writes Kirkus.

YZM: You have written extensively—and well as memorably and beautifully—about your family, including your grandparents, in other essays. Why did you decide to focus exclusively on them now?

KH: I don’t so much decide to write a book as arrive at it. In the case of On Sunset, it’s only now, in my late fifties, with three adult children, that I am beginning to understand what it means to take on the care of a child—a newborn—at 71 and 62—the magnitude of my grandparents’ love. I never felt myself a burden shouldered for my irresponsible teenage mother.

- No Comments

June 5, 2018 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Love, Seduction and Survival—and Always, Paris

In 1950, Glynne Hiller, 26, goes to Paris with her husband, Joe, and her three-year-old daughter, Cathy, so they can all study French in the City of Light. But after a year, Glynne leaves Joe. She doesn’t love him—in fact, she questions whether she’s ever been in love—and she is looking for a more liberated life. Saucy and beautiful, Glynne charms one man after another, including the movie star Jean Gabin. Then she meets a man named Maurice and her whole understanding of love changes. Hiller, now 94, describes this transformation in the memoir Passport to Paris. She talks about her life and writing with Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough.

YZM: Your father, an Egyptian Jew, moved your family from England to America in 1939; did he have a sense of what was coming?

GH: My father started a cotton mill with his brother in Guatemala, before the war started. Both of my brothers volunteered to fight: Eddie, the eldest, in the RAF (Royal Air Force). Max went into the artillery force. Both survived.

Meanwhile, Sally and I, separately, came to America. I came alone, and on the second night, we all came on deck were told we mustn’t make a single sound because there was a German U-boat in the vicinity. And everybody, even the children, were absolutely mum. We all cooperated. And they were already unloading the little lifeboats boats. It was very scary, I have to tell you.

- No Comments

July 15, 2014 by admin

Cut Loose

Leah Vincent, sent away from her Pittsburgh, crowded, ultra-Orthodox family after a tempestuous early adolescence, describes her solo life at age 17 on the margins in New York City—a crucial turning point in her transformative journey from ultra-Orthodox daughter to Harvard-educated author.

There is little room for the single girl in Yeshivish life. For a woman, the rhythm of observance is tied to family. One is either a daughter or a wife. When my sisters had lived in New York, they’d spent Shabbos and holidays with friends from seminary who had family in New York. My sisters were extroverted girls who attracted new relationships like magnets. I had no friends from seminary, and I was not bold enough to make friends with strangers or approach distant cousins and ask if I could join them for a meal.

The worst part of the loneliness was how it compounded my boredom. Television, of course, was forbidden. I did not belong to a shul; as a girl without a husband or father on the other side of the mechitza, I was not expected to attend services. When I got home from work, I ate a slice of pizza or an apple for dinner, said my evening prayers slowly, showered for as long as I could stand, and then lay in bed in my nightgown, baking in the heat, worrying about my future as the moments dragged by.

… What’s next, I wondered. If there is no world of dating and marriage waiting to pull me in, why am I here?

Each day I went through the motions of my job and then counted the long hours of the evening, alone in my apartment. I said the Shema prayer every night before sleep, but heaven seemed unresponsive.

I was always hungry. My minimum-wage check barely covered the rent, the phone bill, and the electric bill. On too many Thursdays I was left with just a slice of bread, a bottle of ketchup, and a few pieces of American cheese. I baked grilled cheese, chewing each piece dozens of times to make it last. I melted cheese and ketchup in a pot on the stove to make a gooey soup, which I choked down. I squeezed the ketchup into circles on my palms and lapped it up. I made a “salad” of bread and cheese and garnished it with ketchup.

In my father’s parables, holy men were always scraping together pennies for weddings or Shabbos food. Poverty and spirituality seemed synonymous. As a child, wearing hand-me-down clothing and living with broken furniture just made me feel proud of our family’s devotion to God.

But there was no spiritual superiority in mixing hand soap and water in an empty shampoo bottle and hoping the resulting mixture would leave my hair shiny and clean. There was no magic in stuffing ribbons of toilet paper into my socks at work to smuggle home. There was no God in the dry taste of stale bread for breakfast, lunch, and then dinner.

After a few weeks, I picked up the phone and called my mother. “It’s Leah.”

“Hello. Hold on—One second, Boorie Tzvi! Everything okay?”

“Yes.” “It’s very hectic now. Okay—” “Mamme,” I cut in before my mother could hang up.

“Things are tough. You know. Even with my job, it’s hard. I don’t always have money for stuff, for food and stuff.” My instinct was to hide the choke in my voice, but I let it go. I wanted my mother to see the evidence, to understand how lost and overwhelmed I was feeling. “Could you help me, maybe?”

“Come on,” my mother said. “Stop being melodramatic, Leah. It’s not like you’re starving. You’re a grown-up now. You have to learn to stand on your own two feet.”

“I know,” I said, wiping my eyes on the back of my hand, ashamed of my outburst. “But it is—it is hard. I’m finding it hard.”

“We’ll see.” My mother sighed. “I just don’t know what happened. It feels like it’s one thing after another with you. You were always such a well-behaved girl. How did you become who you are now? I tell you, sometimes I think you must be possessed by a dybbuk. I don’t know how else to explain who you have turned into.”

A chorus of shouts rose behind her. “I’ve got to go now,” she said. “The children need me.”

A dybbuk? The diagnosis shocked me. Yeshivish Jews were not quick to speak of mystical things, let alone claim possession by a foreign evil spirit. That was the domain of the Hasidim. It was unsettling to hear my mother borrow such a foreign explanation.

If my mother thought I was possessed, then my prayers and stringencies had been for naught. There would be no thrilling conversations about someone’s son or nephew or cousin. There would be no examination of the life of some boy, of the schools and camps he’d attended, friends and neighbors, family, good deeds, personality. A possessed girl. I was marked forever.

A few days later, a twenty-dollar check arrived in the mail. I had hoped for a more robust salvation, but I was grateful for the slice of pizza, jar of peanut butter, bag of apples, bottle of shampoo, and six cans of tuna my mother’s money bought.

Excerpt from Cut Me Loose: Sin and Salvation After My Ultra-Orthodox Girlhood by Leah Vincent. Published by Nan A. Talese/Doubleday Jan 21, 2014. Used with permission.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...