by Yona Zeldis McDonough

The Depth of Grandparents’ Love

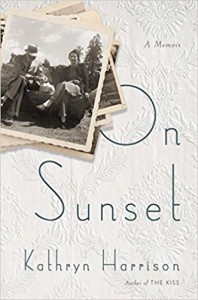

Lilith’s Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough spoke to memoirist and novelist Kathryn Harrison about her latest foray into family history, On Sunset.

Lilith’s Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough spoke to memoirist and novelist Kathryn Harrison about her latest foray into family history, On Sunset.

“Blending family history and mythology, anecdotes and photographs, this book is not simply one woman’s open love letter to two magnificently eccentric grandparents; it is also a testament to the enduring power of memory,” writes Kirkus.

YZM: You have written extensively—and well as memorably and beautifully—about your family, including your grandparents, in other essays. Why did you decide to focus exclusively on them now?

KH: I don’t so much decide to write a book as arrive at it. In the case of On Sunset, it’s only now, in my late fifties, with three adult children, that I am beginning to understand what it means to take on the care of a child—a newborn—at 71 and 62—the magnitude of my grandparents’ love. I never felt myself a burden shouldered for my irresponsible teenage mother.

It’s true, I have written extensively about my family, but it was a family that has presented me with a wealth of material. My mother’s parents were as outsized in their eccentricity as they were in their love. My grandmother’s family alone presented me with people I didn’t need to bring to life: they’d been too alive to ever die. They leapt out of photographs, letters, and particularly the stories that formed the fabric of my early life.

YZM: Your grandfather and grandmother were Jewish; did they observe or celebrate in any way?

KH: They did not. My grandmother turned her back on a faith that had brought her more anguish than she was willing to accept, and my grandfather, whose first wife died, had married into a Jewish family that converted to Christian Science as means of assimilating. Like Unitarianism, it wasn’t so much Christian as it was Christian-y.

YZM: How did they feel about your being raised in the Christian Science faith?

KH: The ethos of the era dictated that children ought to be brought up in some religious tradition, and in terms of my ethical education I suppose Christian Science seemed as good as any other. Having discarded Judaism, it was all that was left to choose from.

YZM: How have the stories of their lives affected you, both as a child and an adult?

KH: How haven’t they? At my grandparents’ ages, they were living in their pasts, and so, necessarily, was I. As I preferred their company to that of other children, I inherited the rich material of their lives, a great good fortune for a writer, but it was the culture of storytelling that made me into one. I’d intended to be a doctor, but I was formed for something else. Or maybe I just knew another way that lives could be saved. I couldn’t have articulated it at the time, but I was learning that we are creatures with narrative souls. Our gods are stories, literally. A trip to the grocery store is a little story. We don’t understand what we can’t narrate. At least I don’t.

YZM: Tell us about the research you did—it seems like it was extensive.

KH: It was, but a lot was accomplished before I was ten—the book would not exist without the stories I was told. The harder part was organizing the material history. As the only child of an only child brought up in the absence of her biological father, and the single surviving member of my family of origin, I inherited every photograph, every document, every object. A daunting mess that filled cartons unopened for many years. I sorted it all into decades, and collated their lives into binders, 1890-1900, 1900-1910. and so forth. Then I made his and hers timelines and another timeline of historical events that had an impact on their lives. I have giant graph paper, three by four feet, and I copied them onto it over and over, drawing them parallel to each other, reading across history to his life and to hers. I revised them eight times. A lot was revealed by that exercise, as each revision was more complex, more accurate.

Two very accomplished archival researchers drilled down through history to help me to fill the holes with details from census reports, armed forces documents, whatever official traces of their lives remained. It was exciting—amazing!—to learn who lived in the boarding house my grandfather’s mother ran in 1890

YZM: You work in several genres; can you talk about the different pleasures—and challenges—of each form?

KH: I’ve written novels, memoirs, personal essays, biographies, and true crime. I’ll divide them into fiction and nonfiction. Fiction is wonderful for the freedom it offers, nonfiction for the chance to reveal what already exists, rather than have to work to make something out of nothing. I tend to oscillate, at least in part because the demands of one relieve the ones of the other.

YZM: What’s the one thing I didn’t ask that you wish I had?

KH: You can ask me why I’m excited right now.

YZM: Why?

KH: I’ve just begun psychoanalytic training. I am so happy to be back in school – I don’t know how it is that I forgot how much I love being a student. And the material is great, the other students are really smart and interesting—and diverse. I’m not giving up writing, of course. My editor was gleeful at the news. All those stories I’ll hear.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.