Tag : anti-semitism

January 26, 2021 by admin

Rep. Elissa Slotkin Calls Out Anti-Semitism in Her Michigan District

There’s a normalization of hate, a permissiveness around antisemitism that has grown, so that people commenting on Facebook pages are alluding to my being a Jewish candidate. There are memes put out by the man I was running against that are for me really right on the line of antisemitism, with me holding money bags and “Slotkin” spelled with a dollar sign. My opponent will not denounce the Proud Boys. He will not denounce these hate groups. It’s one of those things where you know if the ADL and the Southern Poverty Law Center label you a hate group it should be really easy for any candidate around the country to denounce that hate, especially now, and the fact that they won’t shows how normalized and how concerned they are about not offending those folks…

In my district, I have about 4,000 Jews, a small Jewish community of East Lansing. The majority of Jewish Michiganders are closer to Detroit than I live. I live on my family farm; I grew up in the Jewish community of suburban Detroit. Right before Covid, I brought in the Attorney General, I brought in some senior FBI folk from Michigan, and the ADL, because we’ve seen a fourfold increase in antisemitic events in Michigan. It’s spraypainting of swastikas outside of cafes run by more progressive people, the destruction of a sukkah outside of Michigan State Hillel. It’s a series of things; they aren’t violent, but what the FBI really told us about is a ladder of escalation. And when you add to that the conspiracy theories that have now been mainstreamed about Jews, that have literally led to violence in Poway and Pittsburgh. It’s just a different tone and feeling out on the campaign trail.

—

SUSAN WEIDMAN SCHNEIDER and JOAN ROTH, “Elissa Slotkin: How 2020 Looks from the Midwest,” Lilith Blog, October, 2020.

- No Comments

January 25, 2021 by Sarah M. Seltzer

QAnon and its Dangerous Appeal to Women

After Joe Biden was declared the winner of the 2020 presidential election, I joined so many others in allowing myself to feel relief, and, yes, joy. The violence we feared coming on Election Day did not materialize, and it appears that American democracy, so far, survived Trump. But we’re in no way out of the woods: As of publication time, Trump refuses to concede, and is threatening to run again in 2024. After four weary years of threats to just about everything that defines civil society, we will be left facing many evil genies these years have uncorked.

Among the most malignant is QAnon.

Here, in part, is how Wikipedia defines this loose coalition in Fall 2020: QAnon is a far-right conspiracy theory alleging that a cabal of Satan-worshipping pedophiles is running a global child sex-trafficking ring and plotting against US President Donald Trump, who is fighting the cabal. QAnon also commonly asserts that Trump is planning a day of reckoning known as the “Storm”, when thousands of members of the cabal will be arrested. No part of the conspiracy claim is based in fact.

You heard a lot about QAnon during the last crazy months leading up to the election. It became a bigger story after a QAnon supporter, Marjorie Taylor Greene, a Republican, won a Congressional seat in a deep-red section of Georgia. Trump tweeted his congratulations to her, calling her a “future Republican star.” Around this time, we began reading about QAnon all over the media, and seeing photos of people at rallies sporting Q hats and other paraphernalia.

Some call QAnon a “conspiracy theory,” but that’s too simple a definition. QAnon is more like a collective delusion. The Global Network on Extremism and Technology, a think tank studying how terrorists use technology, based at Department of War Studies at King’s College London, defines QAnon as “a militant and anti-establishment ideology rooted in a quasi-apocalyptic desire to destroy the existing, corrupt world order and usher in a promised golden age.”

Up until the election, Q-followers shared one core belief: That Donald Trump will lead a holy war against Satan, aka “the deep state.” In other words, people and institutions associated with liberals: the Clintons and the rest of the Democratic establishment, Hollywood figures (a favorite target is Tom Hanks), mainstream media, and, yes, George Soros.

All of these people, Q-ers believe, are really a gigantic pedophile ring that kidnaps children and harvests their blood. Sound familiar? There’s an obvious subtext of anti-Semitism in these tropes. The Jew as devourer of Christian children, who controls the banks and the world. These images date from the Middle Ages. In the 20th century, they got incorporated into the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion” and then the Nazi propaganda machine.

It started at the fringes of the web early in Donald Trump’s malignant presidency, when the anonymous Q began posting cryptic messages—“drops.” From there Q content migrated into mainstream social media. Followers create deliberately misleading hashtags, such as the innocuous sounding #Savethechildren, thereby drawing in people who might think they’re on a UNICEF-sponsored site, but instead find themselves reading posts like “Better be careful all these kids disappearing and burgers costing next to nothing at all the $2 burger etc. Human meat, you may be eating kids, Say no to fast food burgers.”

Q also hooks in people via their “drops;” searching for and decoding drops for some becomes an addiction. People who’ve fallen down this rabbit hole liken it to getting trapped in a cult.

With so many arms and no clear hierarchy, QAnon is a protean monster, mutating and multiplying like cancer cells, and it is precisely its adaptability to today’s climate that makes it so scary. QAnon, like a sewer flowing through the Internet, collects and absorbs every piece of noxious substance that passes into it from the waste pipes of our culture.

QAnon is not just online. In 2019, the FBI was labeling it a domestic terrorism threat. On the night of Election Day in November, the police in Philadelphia arrested two men at a polling site in a Hummer filled with guns and QAnon literature. Some journalists who wrote about QAnon have gotten death threats. Social media giants Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram keep telling us that they are clamping down on Q content, but this is way easier said than done because of its very protean nature.

But the election is over, Trump was defeated, and QAnon has lost the anointed leader. Need we still worry about the phenomenon and its paranoia? Won’t it just now shrivel up and crawl under a rock? Not so fast. During the fraught week after the election, “Q” went missing. But then he—she?—reemerged, and Q-followers threw out new conspiracy theories onto the Internet. One in particular caught Trump’s attention: Dominion, a manufacturer of voting machines, deleted millions of Trump votes. Trump promptly retweeted it (in all-caps.)

We shouldn’t expect QAnon to go away, but to continue mutating and multiplying. Especially now, in the midst of the pandemic: Catastrophic times are when conspiracy theories thrive (think the Middle Ages, when people blamed the Black Death on the Jews). To that add the fact that for the last ten months, people are isolated at home, glued to their Facebook and Instagram accounts.

As people try to make sense of it all, they pick up the QAnon content hiding behind benign-seeming hashtags and posts. Last summer, Instagram followers, as they scrolled through the site’s panoply of images showing candy-sweet home and-child-oriented consumer products, were also reading that the web-based furniture company Wayfair was really a child trafficking ring. The crazy rumor soon was ripping through social media like a bat out of hell. The Q craze has spread all over the globe, according to Marc André Argentino, a doctoral student at Concordia University who researches QAnon. According to Argentino, QAnon has migrated via social media into more than 70 countries. It has been particularly embraced by the far right fringe in Germany, the New York Times reported in October. Moreover, here in the States, even with Trump gone, QAnon remains in the mainstream. In November, more than a dozen QAnon supporters, all Republicans, ran for Congress. Two— both of them women—won: Marjorie Taylor Greene and Lauren Boebert, from Colorado.

In fact, it turns out that QAnon especially appeals to women.

And this is why, in addition to being a Jewish issue, QAnon is an unrecognized feminist one as well.

Many of today’s far-right movements are testosterone-driven—think Proud Boys and Oath Keepers—replete with muscular imagery. QAnon, on the other hand, attracts women—especially mothers—associated with Trump’s “base”: White, Christian, and not college educated. Likely what happened is that women seized on those aspects of QAnon content that fed preexisting fears—pedophilia, for example—and made it their own. Within the broad anti-trafficking movement, there has always been a moralistic streak, and this movement seizes on that. Women are organizing anti-child trafficking rallies, and posting like mad using #Savethechildren and its countless hashtag variants (#childtrafficking, #DefundHollywood, etc.), where they rant about how Joe Biden is a pedophile, and claiming that the Etsy site sells child porn.

QAnon content has also been creeping into yoga and wellness sites, where you can now find posts in girly fonts about Covid 19 being fake news, and how vaccinations are really a government-led attempt to kill your children—all against backgrounds of pale soothing colors. Argentino, the Concordia University researcher, calls this phenomenon “pastel QAnon.”

“These influencers provide an aesthetic and branding to their entire pages, and they in turn apply this to QAnon content, softening the messages, videos and traditional imagery that would be associated with QAnon narratives,” Argentino wrote on Twitter in September. “This branding is the polar opposite of ‘raw’ QAnon.”

In 1930s Germany, women went crazy for Hitler, and the Nazi Party specifically targeted them through their propaganda machine. Six weeks after Hitler took power in 1933, an exhibit entitled “Die Frauen” opened in Berlin, and Hitler’s propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels gave a speech. “This is the beginning of a new German womanhood,” Goebbels said. “If the nation once again has mothers who proudly and freely choose motherhood, it cannot perish. If the woman is healthy, the people will be healthy. Woe to the nation that neglects its women and mothers. It condemns itself.” At this time of extreme anxiety throughout the world, when misinformation gets transmitted via social media in one second, it bears repeating that the Nazis used whatever media they had at the time to broadcast their vile message. They used children’s books, posters, movies, board games. How primitive such media seem today! Yet they managed to convince Germans of the necessity of a Final Solution to the Jewish “problem.”

Is there a parallel between the Nazi ideation and tactics then and QAnon today?

One big difference between the Nazis and QAnon is just how organized and sharply focused the Nazis were, and how they drew on the systemic anti-Semitism in Europe that dated back to late antiquity. QAnon, in contrast, is much murkier. But QAnon’s goals—a world violently purged of “Satan,” code for liberals, Jews, Hollywood and elites, bears resemblance to the Nazis, who started a war and designed death camps for Jews and other “undesirables” as part of their plan to establish a 1000-year Aryan Reich.

Is it too much of a stretch to make this comparison? We don’t know yet. What we do know is that QAnon has capitalized on how easily misinformation floods the Internet, available to anybody who clicks on a link, and on the other hand attached itself to a resurgent right wing with an anti Semitic flair.

How scared should we be?

Photos: Flicker, Becker1999

Alice Sparberg Alexiou, journalist and author of three books, is a contributing editor at Lilith.

- No Comments

January 12, 2021 by Alice Sparberg Alexiou

QAnon: An Anti-Semitic Conspiracy Theory Sweeps the Nation

Editor’s note: After last week’s Capitol riot and attack featured prominent QAnon flags and symbols, and a figure known as the “QAnon Shaman” was arrested for his role in the insurrection, the connection between the QAnon conspiracy theory and violent racist and anti-Semitic far-right movements is firmly in the spotlight.

But what is QAnon? How exactly is it anti-Semitic? And why does it count so many women among its adherents? Read on for a special preview from our forthcoming winter issue:

- No Comments

October 23, 2020 by admin

Did Alzheimer’s Turn My Husband Into An anti-Semite?

Plenty of Jews who “marry out” ask their new partners to convert. I wasn’t one of them. Yet I’m deep-in-the-bone and dyed-in-the-wool Jewish. My parents were card carrying Zionists from the Midwest who’d met at Habonim, a Zionist youth group. My father dropped out of the University of Michigan in 1949 to go to the newly formed state of Israel.

“Israel?” said his mother, clearly not keen on the idea. “What’s in Israel? Sand, s—- and flies.”

My mother disagreed. Barely 17, and as starry-eyed with the dream as he was, she followed him there. They lived first in a kibbutz and later on a moshav; my brother was born in the first and I in the second, making me a sabra, with a Hebrew name and Israeli birth certificate. My parents left Israel when I was a year old, but the country loomed large, almost mythical, throughout my childhood, even though I didn’t return until I was 18. When I did, it felt like a homecoming.

But when I fell in love with my husband, it was his very non-Jewishness that made my Jewish girl’s heart flutter. Born and raised in Portsmouth, NH, he was a Yankee through and through, part of a big, extended Catholic family, most of them

still in the area.

The first Christmas we knew each other, he brought me to his boyhood home, a charming white house. He raved about how the backyard had been filled with lilacs in the spring; I could almost imagine their scent. We passed his Nana’s house on State Street, where he’d stop by; together, they did the Jumble in the newspaper while he ate a generous slice of the incomparable apple pie she’d baked. Then there was the Whipple Elementary School, the pond where he’d learned to skate, his father’s sporting goods store on Market Street, where it had been his job to string the tennis racquets and dust the stacked boxes of model airplanes. Molson’s, the drugstore/ luncheonette, was gone, but he wished I’d been able to taste the ice cream Mr. Molson churned in the basement—vanilla, chocolate, peach, and his favorite, coffee.

We drove along the coastline—all 18 miles of it—and he introduced me to his cousin Bobby, who had a lobstering business. As a teenager, he’d worked for Bobby during the summers, and in the years before sunscreen was as much a requisite as toothpaste, he told me his skin burnt as red as those poor lobsters when thrown into pots of boiling water. Further up the coast was where his family would rent a cottage for a few weeks in August; he and his siblings dug for clams along the shore and his mother cooked them in a pot right on the beach. A few years later, as a budding artist, he went there on his own, setting up shop on the boardwalk and drawing portraits of passers-by. We visited the cemetery where his relatives were laid to rest: grandparents, uncles and aunts—most memorably to me the one called Elspeth.

I came back from that visit in love with Portsmouth—and with him. His New England upbringing seemed to have been lifted straight from a Norman Rockwell illustration. Its wholesomeness and its divergence from my own spoke to me. I didn’t need or even want him to be Jewish—I wanted him to be just who and what he was.

The attraction of opposites was reciprocal. If there had been any Jews during the years he lived in Portsmouth, they must have stayed on the sidelines, for he didn’t know them. So, to him, I was an exotic creature—dark-haired, fast-talking, hands

always moving. If his R.P.M. was 16, mine was 78—on a slow day. He loved the Yiddish words I tossed lightly in his direction—gatkes was a particular favorite—and the world they conjured. He could listen to my grandmother’s endless (and endlessly

repeated) stories about the “old country” with true and rapt interest; basking in his attention, she dubbed him “a prince.”

We each fell in love with the way the other was not like us—vive la difference. And it was those differences that carried us happily through our life together. When we married, it was—by mutual agreement—in a civil ceremony, but we celebrated

Pesach and Rosh Hashana with my mother. When our son was born, it was he who urged the bris rather than the purely medical circumcision offered by the obstetrician. I took to his holidays, Easter and most especially Christmas, which I celebrated with all the suppressed longing that only a Jewish girl can have.

We raised our children with a sense of respect for each of our backgrounds; for them, there was no sense of “other” but a strong sense of “both.” I occasionally experienced flack from other Jews who criticized my decision to intermarry, and

especially for not giving our children a more tangible Jewish education. I brushed them off. We were happy. Case closed.

And then, in his seventies, my husband received a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, a development that changed his life—and mine. As a spouse-turned-caretaker, I struggled with my new role, trying to frame it within the positive. He still knew me, and he still knew the kids. He was still moved—transported even—by the kind of art

he’d always loved. He still took photographs, his life’s work, although he no longer used the Leica that had practically been another limb, or spent hours in the darkroom developing them. He still loved coffee ice cream.

Between my reading and my discussion with his doctors, I knew what to expect: the repetition, the disorientation, the agitation, the sun-downing. I steeled myself against his occasional outbursts, the paranoia and delusions—I was having an affair with the contractor who redid our kitchen, I had tried to poison him, I was stealing his money, I was planning to leave him.

None of this was even remotely true, but reason didn’t have any purchase against the erosion taking place in his mind. I found I could either try to distract him—a phone call to one of our children might help—or wait it out. The moods always

passed, as did his memory of them. “I said that?” he’d ask incredulously. “I didn’t mean it. I’m so sorry.”

But then there was a night on which, in the middle of such an episode, he uttered these words: “You know what the problem is? It’s that you’re a Jew and Jews are a vile people—you’re from a vile race.”

It was the most shocking thing I’d ever heard him say, and for a moment, it seemed to upend everything I thought I knew about him. About us. It was also, in a strange, dark way, kind of…funny. After all, it was a little late to be bringing it up now; the Jewish card had been played early on—from the beginning, in fact.

He went on in this vein for a while and then something in his mood turned; his anger lifted, forgotten. But I couldn’t forget. The other insults, the accusations had been easier to disregard. These words were insidious, heat-seeking missiles aimed right at my heart. What if on some inchoate level, he’d always felt this way? Wasn’t that the old warning? He says he loves you now, but the first time you have a fight, it’ll be dirty Jew. That won’t be us, I had smugly thought. Well, now it seemed that it was.

And that wasn’t the last of it either. On several other occasions, he’d start in on those same accusations, using the same or similar language. Of course I knew that though it was his voice I was hearing, those weren’t his words. They were lines from

a script deeply embedded in our culture and written by the disease, the one that had taken up residence in his brain and was inexorably reshaping it.

But knowing that didn’t entirely diminish their power to wound. Instead, they dredged up every anti-Semitic taunt I’d ever heard: Christ-killer, big nosed, greasy, greedy, money-loving, money-grubbing. Their venom made me question my faith in who we’d been together, and the life we’d made. What if I’d been wrong about all of it, and that there was—and always had been—some deep and yawning chasm between us? What if, as Tom Lehrer had sung back in the 1960’s, “…the Catholics hate the Protestants/the Protestants hate the Catholics/the Hindus hate the Muslims/and everyone hates the Jews”?

Then, for reasons not readily understood, the attacks—at least the anti-Semitic ones—stopped. At the recommendation of his neurologist, his medication was increased, and his moods became less volatile. I learned to see some of the triggers—a touch of impatience in my voice, for instance—and to control them.

We are, for the moment, on safe ground. Or safe enough. He can still laugh at a Yiddish phrase; I’m still the Queen of Christmas. But as has been made clear to me, this disease has only one direction, and that direction is down. I can only hope I’m strong and resilient enough to be remain the loving wife I’ve always tried to be, and the loving caretaker I’ve had to become. Part of that will mean stopping my own ears to the hateful words that can threaten to undo it all.

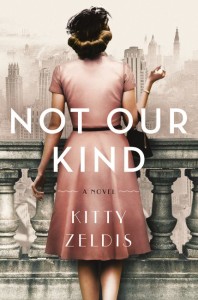

Yona Zeldis McDonough’s most recent novel is Not Our Kind,

written under the pen name Kitty Zeldis. She’s been Lilith’s

Fiction Editor since 2000.

- No Comments

May 21, 2019 by Sharrona Pearl

Mel Gibson’s ‘Rothchild’ Film Ditches the ‘S’ But Keeps the Anti-Semitism

As the endless reboots, remakes, and superhero movies show, no Hollywood exec is seriously asking if we need another movie about a given topic. Movies aren’t about need. They are about want. Desire. Wish fulfillment and fantasy. Movies are where we go to imagine other worlds, and be transported from ours.

So what does it say about our world that Hollywood has greenlit a major film that uses an almost identical name to Rothschild, a name almost synonymous with anti-Semitic tropes? Whose subject is a wealthy and corrupt family who will stop at nothing in pursuit of the almighty dollar? What does it say that the film stars one of the most notoriously anti-Semitic actors of our time—you know, who I mean? If you’re not aware, google Mel Gibson and his vile comments.

- No Comments

October 29, 2018 by Liat Katz

Carrying the Torah for Those We Lost in Pittsburgh

On Saturday, as I was sitting in synagogue during Shabbat services, someone began locking the doors of our shul. The shootings had just happened in Pittsburgh, and there was reason to fear that it could happen anywhere.

On Saturday, as I was sitting in synagogue during Shabbat services, someone began locking the doors of our shul. The shootings had just happened in Pittsburgh, and there was reason to fear that it could happen anywhere.

I have had mixed feelings about my relationship to Judaism and my specific relationship to worship, but Saturday’s events strengthened my resolve. As I heard the news of the eleven people who lost their lives, I thought about those people worshipping as I was before being gunned down.

Beyond the communal and cultural aspects of being Jewish, which I have always been proud of, I have been thinking about the meaning of Jews reading Torah—for the eleven that died, for Jews around the world on that same Saturday morning, and for me and my fellow Jews in a small synagogue outside of Washington, DC.

- 2 Comments

October 29, 2018 by Karen Paul

To My Friend, Whose Celebration Was the Day of a Massacre

We were at the mikveh on Friday, nine of us, seven celebrants and two attendants who witnessed our joy as you marked your birthday and a moment of pause in your high profile, high impact job. It was a soul-filled morning, saturated with reflections on some relationships that spanned decades, and some that were bright and new but still profound.

You had never been to the mikveh, the ritual bath that cleanses and prepares Jews for many roles – that of sexual preparedness and procreation, that of convert, that of celebrant. Preparing for immersion strips you down to your barest place, with not a spot that can come between you and the waters. The waters which are rain waters, waters that have been a part of this earth for millennia, touching your skin, soothing your heart, marking your passage.

- No Comments

October 3, 2018 by admin

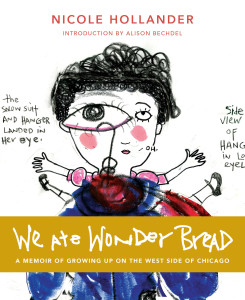

I Say, “I’m Jewish.”

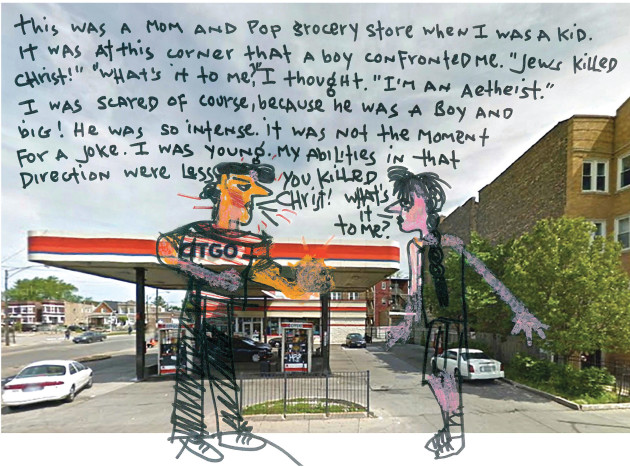

Hollander, beloved creator of the “Sylvia” cartoon strip, tells her own story in this new book (above). Her irony-laden, cigarette-smoking Sylvia is replaced here with autobiographical vignettes and pungent images from the cartoonist’s Jewish girlhood in Chicago.

I remember going to the corner store for Wonder Bread. We were always admonished by our mothers not to squeeze the bread. If you squeezed it, it became a tiny wad and could not be used to make sandwiches or anything but spitballs.

A boy I recognize vaguely from school stands very close to me and hisses: “You killed Jesus.” I was of course frightened of him, his size and intensity, but I had been raised by an atheist and felt no guilt about something I didn’t think existed, like God. I was too young to say: “Really, the Jews killed Jesus, all of us? Did you ever see us in a room together trying to agree on anything?”

My experience of anti-Semitism was very limited as a child. We lived in a mainly Italian neighborhood, but the building we lived in was completely Jewish.

But I did hear slurs at neighborhood parties. I was a kid. I looked like all the other dark-haired kids and occasionally someone in the group would say someone “jewed” him down. “Jews have all the money, there are no poor Jews, Jews stick together.” I could feel the remark coming. I was on the alert. Here is a group of people who are among their own kind. Why should they be careful about what they say? Suddenly the remark is made and I feel the spotlight on me. I am frozen and yet highly alert, my mind is working at top speed.

The idea that I might let the remark pass is certainly tempting, but not an option. I have a duty to all those Jews who died in the camps.

I say: “I’m Jewish.” There is a terrible silence. These are nice

people. I know them all. They are ashamed. They apologize. They say they didn’t know. They didn’t mean it.

I feel the urge to reassure them that I will forgive them and that I am not permanently injured.

The moment passes, everyone starts laughing and talking again, but I could ruin it all in a minute.

- No Comments

September 12, 2018 by Kitty Zeldis

Anti-Semitism Among the WASP Elite

The idea for my novel Not Our Kind was born at Vassar College, where I was a student in the 1970s, where there was enough visible diversity to make a Jewish girl feel she was not alone. I encountered plenty of Jews, both students and faculty. Yet while I didn’t experience much overt anti-Semitism, I felt keenly aware that Vassar had historically excluded people like me—I was the “not our kind” of my eventual novel’s title.

I could feel it in the manners, the mores, the very air around me. Vassar was a WASP institution and bastion, and I knew I didn’t entirely belong. In fact, it was at Vassar that I acquired the nickname that became my pen name. I had commented to a friend that my Hebrew first name and Polish surname felt all wrong and that I should have been called Katherine Anne Worthington; he jokingly responded by calling me Kitty. It’s a name that stuck.

The anti-Semitism at Vassar was occasionally overt— my freshman roommate casually noted, “Well, your people did murder our Lord,” a remark for which I then had no ready reply. But it was the more passive, almost nonchalant anti-Semitism that stung most. I remember an English lit class in which we’d been reading Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot and I said that I found the stereotypical characterizations of Jews in their poetry—greedy, money-grubbing, hook nosed and so forth— upsetting. A fellow student raised his hand and said, “Oh, well, that’s what everyone was like back then,” as if that should have cancelled out my discomfort, and made it, somehow, all right. And then there was the memorable evening that I went to hear a lecture on 18th century Rococo painting that was to be given by a well-regarded scholar visiting from Germany. Before he came to the lectern, someone from the Art History department read a short bio by way of introduction. I don’t know what I expected to hear, but it surely wasn’t that during World War II, this man had been a high ranking official—a commander, a general, I don’t recall which—in the military. A Nazi, in other words, though the word was not actually said.

my freshman roommate casually noted, “Well, your people did murder our Lord,” a remark for which I then had no ready reply. But it was the more passive, almost nonchalant anti-Semitism that stung most. I remember an English lit class in which we’d been reading Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot and I said that I found the stereotypical characterizations of Jews in their poetry—greedy, money-grubbing, hook nosed and so forth— upsetting. A fellow student raised his hand and said, “Oh, well, that’s what everyone was like back then,” as if that should have cancelled out my discomfort, and made it, somehow, all right. And then there was the memorable evening that I went to hear a lecture on 18th century Rococo painting that was to be given by a well-regarded scholar visiting from Germany. Before he came to the lectern, someone from the Art History department read a short bio by way of introduction. I don’t know what I expected to hear, but it surely wasn’t that during World War II, this man had been a high ranking official—a commander, a general, I don’t recall which—in the military. A Nazi, in other words, though the word was not actually said.

- 1 Comment

April 12, 2018 by admin

Jewish Lesbian Feminist Goes Undercover to Report on the Alt-Right

When award-winning journalist Donna Minkowitz attended a conference sponsored by the innocuously-named American Renaissance organization last summer, she knew she would be rubbing elbows with leaders of the alt-right.

Minkowitz, a self-described “secular, Jewish, lesbian feminist and leftist,” told Eleanor J. Bader about covering the event for Political Research Associates, an independently-funded social justice think tank based in Somerville, Massachusetts. She also spoke about her earlier interactions with conservative organizations.

Eleanor J. Bader: You began reporting on the right-wing back in the 1990s. How and why did you get started on this beat?

Donna Minkowitz: I was the Village Voice’s reporter on LGBT issues, and when the anti-gay Christian right started to become active again in the 1990s, I found myself becoming increasingly terrified… I decided to cover it for Out Magazine. I was in my late 20s at the time and went completely undercover—I wore conservative, feminine dresses and a very femme-y wig. It was a really intense few days.

EJB: Did this year’s AmRen conference have a particular theme?

DM: The main message was that white people are smarter and better than everyone else and if only these “inferior” people of color were not around to drag them down, they could achieve the great things they imagine. AmRen says it welcomes Jews, but anti-Semitism was at the conference—it was hiding in plain sight. Eli Mosley, the head of the virulently anti-Semitic Identity Evropa, was at the conference and he and other attendees continually tweeted anti-Semitic messages; there were also loads of anti-Semitic books for sale, including The Turner Diaries, which advocates Jewish extermination…

EJB: Were you surprised by anything that you saw or heard?

DM: I was pretty stunned by how Handmaid’s Tale-ish their plans for women in the “white ethnostate” were.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...