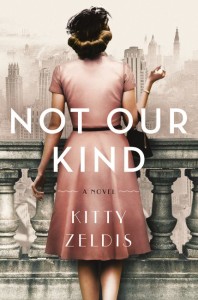

by Kitty Zeldis

Anti-Semitism Among the WASP Elite

The idea for my novel Not Our Kind was born at Vassar College, where I was a student in the 1970s, where there was enough visible diversity to make a Jewish girl feel she was not alone. I encountered plenty of Jews, both students and faculty. Yet while I didn’t experience much overt anti-Semitism, I felt keenly aware that Vassar had historically excluded people like me—I was the “not our kind” of my eventual novel’s title.

I could feel it in the manners, the mores, the very air around me. Vassar was a WASP institution and bastion, and I knew I didn’t entirely belong. In fact, it was at Vassar that I acquired the nickname that became my pen name. I had commented to a friend that my Hebrew first name and Polish surname felt all wrong and that I should have been called Katherine Anne Worthington; he jokingly responded by calling me Kitty. It’s a name that stuck.

The anti-Semitism at Vassar was occasionally overt— my freshman roommate casually noted, “Well, your people did murder our Lord,” a remark for which I then had no ready reply. But it was the more passive, almost nonchalant anti-Semitism that stung most. I remember an English lit class in which we’d been reading Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot and I said that I found the stereotypical characterizations of Jews in their poetry—greedy, money-grubbing, hook nosed and so forth— upsetting. A fellow student raised his hand and said, “Oh, well, that’s what everyone was like back then,” as if that should have cancelled out my discomfort, and made it, somehow, all right. And then there was the memorable evening that I went to hear a lecture on 18th century Rococo painting that was to be given by a well-regarded scholar visiting from Germany. Before he came to the lectern, someone from the Art History department read a short bio by way of introduction. I don’t know what I expected to hear, but it surely wasn’t that during World War II, this man had been a high ranking official—a commander, a general, I don’t recall which—in the military. A Nazi, in other words, though the word was not actually said.

my freshman roommate casually noted, “Well, your people did murder our Lord,” a remark for which I then had no ready reply. But it was the more passive, almost nonchalant anti-Semitism that stung most. I remember an English lit class in which we’d been reading Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot and I said that I found the stereotypical characterizations of Jews in their poetry—greedy, money-grubbing, hook nosed and so forth— upsetting. A fellow student raised his hand and said, “Oh, well, that’s what everyone was like back then,” as if that should have cancelled out my discomfort, and made it, somehow, all right. And then there was the memorable evening that I went to hear a lecture on 18th century Rococo painting that was to be given by a well-regarded scholar visiting from Germany. Before he came to the lectern, someone from the Art History department read a short bio by way of introduction. I don’t know what I expected to hear, but it surely wasn’t that during World War II, this man had been a high ranking official—a commander, a general, I don’t recall which—in the military. A Nazi, in other words, though the word was not actually said.

It felt like my cheeks had burst into flame. I stood up and in my haste to leave, tripped over the feet of the people still seated in my row. The next day, I paid a visit to the German department; by then I had learned that they had been the ones to issue the invitation. I shared my feelings with the young professor from Bavaria who was the chairman. He was very handsome, with dark hair and eyes, and he seemed quite perplexed by my response. “We had no idea this would offend anyone,” he said earnestly. Well guess what? It did.

The memory of that defining moment lived inside me for decades, and it helped spark Not Our Kind, a novel I’ve described as Gentlemen’s Agreement, only with two women at the center. The anti-Semitism of the post-war period in America found expression in the quotas imposed by colleges (Vassar would have been one of those) and universities, as well as the apartment buildings, hotels, and entire towns which proudly called themselves restricted. This was the landscape I sought to construct and evoke as I wrote.

But anti-Semitism is more the by-product than the theme of Not Our Kind. I also wanted to explore how Jews made their way in the non-Jewish world, because that was my story too. Unlike the strictly Orthodox who remain sheltered within and nurtured by the confines of their communities, my protagonist Eleanor Moskowitz seeks a place in a larger world that often rebuffs and excludes her.

How does she find happiness? And with whom—will it be the Bellamys—the Park Avenue family who serve as Eleanor’s initiators? How will they reevaluate their own received prejudices when faced with Eleanor as a unique individual, and not the stereotype they have never had reason before to question?

Though this story takes place in 1947, so many of the issues with which my characters grapple still resonate: overcoming prejudice, finding acceptance both despite and because of our differences.

I hope Not Our Kind will give those issues a refreshed and renewed sense of urgency for today’s readers.

Kitty Zeldis is the pen name of an author of seven novels and twenty-books for children.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.