The Lilith Blog

April 13, 2016 by Elana Sztokman

Passover: Freedom for Women NOW—Not 3000 Years Ago

“Passover,” Arthur Szyk, 1948. Yeshiva University Museum.

There is no holiday that brings out the screaming in my head as much as Passover.

There are two sets of noise that take hold of my brain at this time of year: the pre-Pesach (Passover) trauma and the Seder night trauma. Or as I have come to experience it, the trauma created by women’s stuff, and the trauma created by men’s stuff.

Growing up, the pre-Pesach anxiety began as soon as Purim was over. We were only allowed to eat from a pre-determined collection in the kitchen, we were on a schedule around what rooms were already sterilized, and my mother’s mood went from the usual cold and cranky to the downright hostile. Nothing was ever right, we walked on eggshells, and life was insane and frenetic. Although I often wonder how many of my traumas are from religion and how many are from my particular family, in this particular case I have come to learn that this kind of thing was going on not only my own house but also in many Jewish homes around the world. Even women of privilege engage in the panic. (I’ll never forget the time, years ago, when a mother frantically came to pick up her daughter from a play date around a week before Pesach, saying, “Hurry, I have to rush home and watch my cleaning lady do the kitchen.”) Pre-Pesach insanity, it seemed, was the Women’s Way, no matter how you celebrated the holiday.

I’ve been living in Israel for over 20 years, and it is still astounding for me to watch how this culture takes over Jewish women’s lives, no matter what kind of religious observance they adhere to during the year. Conversations in shops, on the street, and online, revolve around Jewish women of all backgrounds managing the minutia of obsessive cleaning, shopping, and cooking. There seems to be an uncontrolled lust for women comparing themselves to one another—who started cleaning and cooking earlier, who is having more guests, who is more efficient, who is more creative, and ironically also who has more time-saving hacks. Facebook doesn’t help, by the way.

Growing up in Orthodox Brooklyn, I found this pre-Pesach cleaning-cooking-hosting-mania was compounded by the other assault on women’s bodies: clothing shopping. Our job, as religious girls, was not only to manage the kitchen, but also to look gorgeous as we did it. We prepared our shul and Seder outfits meticulously and expensively, down to the last perfectly-matching accessory. But let me tell you something: there is nothing quite as dysfunctional within the female experience as surrounding yourself with copious amounts of food and then forbidding yourself from eating it. Women’s and girls’ table conversation, once we finished serving, invariably revolved around calories, points, fat content, carbs, gluten, GI, cellulite, whatever. (Each year, the measures for what we should or shouldn’t eat changed, led by trends announced by The New York Times. This added to women’s competition not only over who was thinnest, but also over who was the most in-the-know about how to effectively lose weight.)

- 2 Comments

April 12, 2016 by Pamela Rafalow Grossman

Gayle Kirschenbaum, “Accidental Therapist” for People Who Don’t Get Along With Their Mothers

It’s almost Passover—a time of renewal, of course, and a time to reflect on themes of freedom from enslavement.

There is a special Haftorah for the Shabbat before Passover. It’s the conclusion of the book of Malachi, and its last passage urges familial reconciliation—with a dire warning: “That you may turn the hearts of parents to their children, and the hearts of children to their parents, lest destruction smite your land.”

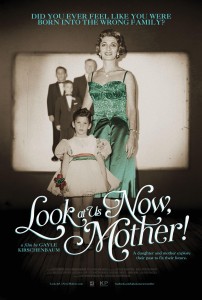

I approach an interview with documentarian Gayle Kirschenbaum with these things on my mind. Her newest film, the feature-length “Look at Us Now, Mother,” has won multiple awards on the festival circuit and is currently playing in New York, Los Angeles, and Boca Raton (see here for future screenings); it moves on to Kirschenbaum’s native Long Island in time for Mother’s Day. The film examines Gayle’s often-fraught relationship with her mother, Mildred, and her attempts to heal from familial pains of the past. The project evolved from a short documentary of Gayle’s called “My Nose” (2007), in which Mildred tries to convince her daughter that she dearly needs a nose job and Gayle agrees to go with her for consults with a few plastic surgeons—as long as she can film the process. (The conclusion: No one but Mildred finds Gayle’s nose to be any kind of problem.)

I approach an interview with documentarian Gayle Kirschenbaum with these things on my mind. Her newest film, the feature-length “Look at Us Now, Mother,” has won multiple awards on the festival circuit and is currently playing in New York, Los Angeles, and Boca Raton (see here for future screenings); it moves on to Kirschenbaum’s native Long Island in time for Mother’s Day. The film examines Gayle’s often-fraught relationship with her mother, Mildred, and her attempts to heal from familial pains of the past. The project evolved from a short documentary of Gayle’s called “My Nose” (2007), in which Mildred tries to convince her daughter that she dearly needs a nose job and Gayle agrees to go with her for consults with a few plastic surgeons—as long as she can film the process. (The conclusion: No one but Mildred finds Gayle’s nose to be any kind of problem.)

“I never bought into my mother’s criticism—of my nose, my hair, my behavior. I didn’t take it personally, but I wanted to know why it happened,” Gayle says by phone from her apartment in New York (with Mildred, who’s in town from Florida for film screenings, by her side). “It didn’t affect my self-esteem, but it affected my feelings about loving and being loved. And I was always looking for answers. I knew I had to forgive her.”

After “My Nose,” “I saw the need to make the feature film,” Gayle says. “I felt I became an ‘accidental therapist’ for the people dealing with their own issues with their parents and families.”

Photo by Gerald Kirschenbaum

“Look at Us Now Mother” is not what most would call an easy ride. There are photos of young Gayle—usually in formal dresses—gazing up at a glamorous mother who doesn’t seem to know she’s there. (“I’d be dressed up in these things,” Gayle recalls now, “and then break out in rashes!”) There is film footage of her trying unsuccessfully to climb onto her mother’s lap. There is a blistering recollection of Mildred’s parental behavior from one of Gayle’s close childhood friends. There is even footage of current-day Gayle working with her mother in family therapy.

- No Comments

April 7, 2016 by Esther Sperber

The Shadow of Zaha Hadid

Zaha Hadid via Knight Foundation

I was sitting at my office desk, Thursday morning, March 31, multitasking as usual; checking my email, drafting plans for my sister’s apartment renovation in Tel Aviv, logging data into my bookkeeping software, and (I confess) checking Facebook once in a while. I scrolled through the feed of vacation photos, op eds and political comedy when I suddenly caught my breath – Zaha Hadid had died of a heart attack, age 65.

I’ve been thinking about Hadid’s death since its startling appearance in my Facebook feed. Had you asked me on Wednesday who my architectural heroes were, I probably would not have mentioned her name. She was amazing, but my role models are smaller, more approachable, perhaps more like I want to see myself when I grow up. I might have mentioned Carlo Scarpa, whose buildings I insisted on visiting on a recent trip to Verona and Venice. Or maybe I would have noted Jeanne Gang, whose work is both intelligent and poetic. Zaha, I would have said, was too unique and too brilliant. She imagined things no one had ever seen, and she was able to make these fantasies become physical realities. I could not see myself in her.

Nevertheless, I keep thinking about her, staying up late, reading admiring obituaries, snappy stories calling her a “diva” and online posts from young students. If she was not my hero, why does her death matter so much?

- 3 Comments

April 5, 2016 by Hanna R. Neier

Jennifer S. Brown, Author of “Modern Girls,” Talks Mother-Daughter Drama and Choosing Abortion in the 1930s

Dottie’s got a great job in Manhattan. She blows her salary on the latest fashions, escapes to the country with her friends when the city is stifling, and is in love with her boyfriend of three years. Her mother’s a stay-at-home, spends her life pushing her kids to make the most of theirs and dreams of her young political days when life used to mean so much more.

Dottie’s got a great job in Manhattan. She blows her salary on the latest fashions, escapes to the country with her friends when the city is stifling, and is in love with her boyfriend of three years. Her mother’s a stay-at-home, spends her life pushing her kids to make the most of theirs and dreams of her young political days when life used to mean so much more.

It’s a timeless story—could be happening right now. Only it’s happening in 1935. And Dottie’s pregnant. And so is her mom. And neither is very happy about it.

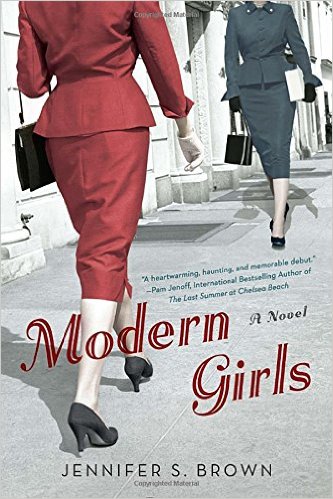

Jennifer S. Brown’s debut novel, Modern Girls (NAL/Penguin, April 5, 2016), handles timeless issues of women’s choices, setting it for added drama in the Jewish world of the Lower East Side before World War II. Lilith sat down with the author to talk about mother-daughter drama, having it all, and what makes a Modern Girl.

HRN: This story has some classic relationship drama—mother-daughter dynamics, lovers who can’t commit. Why set it in Lower East Side, New York in 1935? What was the inspiration?

JSB: When I was pregnant with my first child, I went through the genetic testing common for Ashkenazi Jewish women. I asked my father for our family’s medical history, and I was shocked when he told me, “My grandmother had uterine cancer. They thought it was because of that botched abortion, but I’m pretty sure abortions don’t cause cancer.” I started turning the idea over in my mind, playing with it. Why would a married woman during the Depression not want a child? How are her issues different from an unmarried woman? Starting from there, the novel began to take shape.

- 1 Comment

April 4, 2016 by Rebecca Halff

I’m Denominationally Conflicted. Are You?

I’ve been “denominationally conflicted” for a while now—and I suspect I’m not the only one whose intellect doesn’t match her emotions when it comes to Judaism. While I believe fiercely in egalitarianism (although I did not have a bat mitzvah, I loved reading from the Torah for three of my siblings’ bar and bat mitzvahs), my heart doesn’t soar in the Conservative shul to which my family belongs to the way it does in ultra-Orthodox settings.

My attempts at understanding the disconnect between what I believe and what I feel have yielded only vague hypotheses. Sometimes I think it’s the women-only spaces created by gender-segregated services which appeal to me. Maybe it’s something evoked by the accents, the intonation, the melodies, the mannerisms, the motions. It could also be the cozy, communal feeling of being outsiders together which comes with a recognizable dress code and a set of habits and traditions often viewed by gentiles and secular Jews as mysterious and unsettling.

As a kid, I spent my summers at a girls-only Lubavitch sleepaway camp in the Pyrenees Mountains in France. Whereas at home I adhered to no dress code whatsoever, in camp we all wore opaque wool tights, ankle-length skirts, long-sleeved shirts that covered our collarbones, and close-toed shoes. Buttons and zippers were frowned upon. “When a door is open, you want to peek inside,” instructed one of our counselors, “So too buttons make men want to peek inside.” I was nine years old, but I recognized immediately that this was a creepy thing to say, and filed it under the category of “things to report to my parents when I get home.” (However ridiculous I considered the counselor’s ideas, however, it does not escape me that I’ve remembered her exact words for all these years—clearly they made an impact.)

- 2 Comments

April 1, 2016 by Leida Snow

Maybe They Won’t Let Me Back In

After the attacks on Brussels, after Paris and Madrid and 9/11, travelers everywhere are having second thoughts, and many worry even about waiting on line at immigration and customs in New York because they know they’re a soft target. But I can’t remember a time when coming home didn’t fill me with dread. Even before seeing the signs for Citizens and Non-Citizens, my mouth feels like I swallowed dirt. No matter how warm or cold the area, the sweat starts to form little round beads on my forehead, and my stomach feels like birds are inside fighting. The trembling is the worst. I’m scared the officers will see that my hands are shaking and think I’m suspicious.

After the attacks on Brussels, after Paris and Madrid and 9/11, travelers everywhere are having second thoughts, and many worry even about waiting on line at immigration and customs in New York because they know they’re a soft target. But I can’t remember a time when coming home didn’t fill me with dread. Even before seeing the signs for Citizens and Non-Citizens, my mouth feels like I swallowed dirt. No matter how warm or cold the area, the sweat starts to form little round beads on my forehead, and my stomach feels like birds are inside fighting. The trembling is the worst. I’m scared the officers will see that my hands are shaking and think I’m suspicious.

I try to calm myself. I’m not carrying anything illegal. I’ve never been arrested. I’m a proud American, New York City-born and bred. My parents were American-born, too.

I know practically nothing about my grandparents, not even the towns in Russia where they came from. My father’s parents, and my mother’s father, died before I was born. But I knew Grandma Fanny, and I had been told how hard it was for her to come to America. Could that be why coming home feels so fraught?

- No Comments

March 31, 2016 by Nora Lee Mandel

What Two Frank New Documentaries Tell You About Women’s Lives

Two mature Jewish women artists premiered their latest and deepest plumbing of private lives at the Museum of Modern Art’s Doc Fortnight 2016: An International Festival of Nonfiction Film in NYC in February. Always intriguing, the 15th annual series showcases recent documentary films from around the world that, per the curatorial selection committee, push the boundaries “between contemporary art and nonfiction practices and reflect on new areas of documentary filmmaking.” Natalie Bookchin’s “Long Story Short” and Beth B’s bio-doc of her mother Ida, “Call Her Applebroog,” both attracted large appreciative audiences of family, colleagues, and fans.

Media artist Natalie Bookchin brought “Long Story Short,” a powerful project she had just finished editing after several years of filming—and listening closely to—diverse individuals at eight service organizations on the West Coast, including homeless shelters, food banks, adult literacy programs, and job training centers.

Bookchin gives intimate screen time to over 100 people usually hidden in plain sight—those struggling in poverty. Women, men, old, young, middle-aged, veterans, unemployed, single parent, homeless, ex-con, with HIV, most African-American and Latino (none apparently Jewish) in the Los Angeles and Oakland areas, they all face her laptop’s camera for video blogs. She takes the next, extended step from the brief Story Corps interviews heard on NPR and the captioned photographs of Brandon Stanton’s Humans of New York portraits.

Starting in the midst of the recession and last presidential election, she asked each participant: “What do you think people should know about you?” In their own words, her respondents express their feelings—many of them heartbreaking—on their childhoods and how they got to this difficult point. Encouraged to share what “I usually don’t tell people,” they all stress that “rich people don’t understand” how hard life is without a job, a phone, or an address. Women are especially frustrated that the certifications and degrees they’ve worked hard to achieve neither protect them from being laid off nor help them get any higher up the ladder. But they are proud of “being creative” with whatever they can afford, like improvising curtains in a shelter.

- No Comments

March 30, 2016 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Aviva Orenstein, Author of “Fat Chance,” Talks Fat as Feminist Issue and Jewish Women and Food

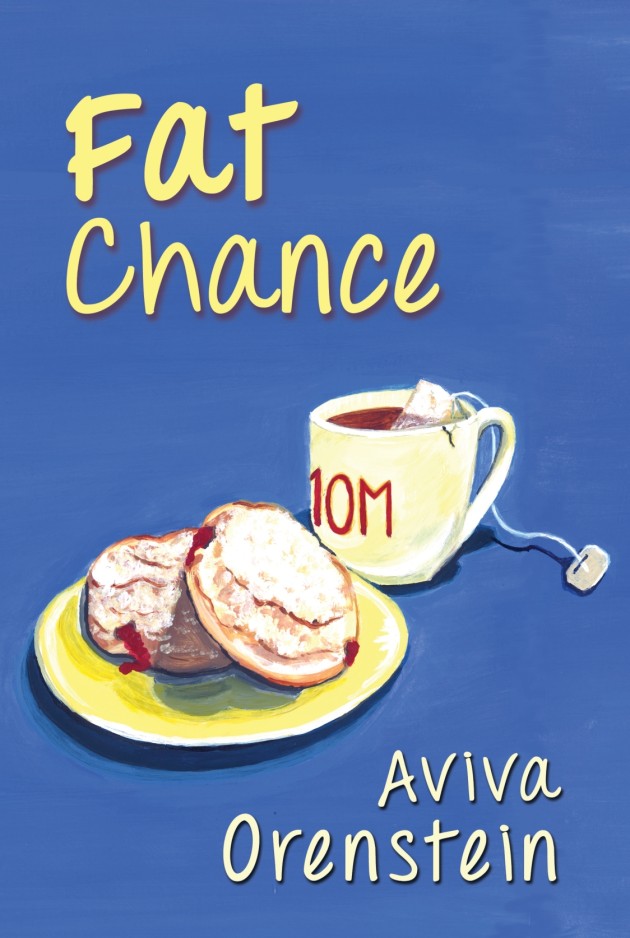

Confident at work but clueless at love, Claire is forty and zaftig—not a combo that she imagines can resolve the romance gap. Dealing with her father’s death and an angry teenager doesn’t make things any easier. With no help from her ex, who is distracted by remarriage to a much younger woman, Claire copes by relying on a faithful circle of friends, a wicked sense of humor, and a new interest in fitness here. When she meets Rob, a beguiling, slightly pudgy man at the gym, there is an instant connection that she hopes will lead to more. Maybe, just maybe, she can haul the composure she finds at work into the gym with her…

Confident at work but clueless at love, Claire is forty and zaftig—not a combo that she imagines can resolve the romance gap. Dealing with her father’s death and an angry teenager doesn’t make things any easier. With no help from her ex, who is distracted by remarriage to a much younger woman, Claire copes by relying on a faithful circle of friends, a wicked sense of humor, and a new interest in fitness here. When she meets Rob, a beguiling, slightly pudgy man at the gym, there is an instant connection that she hopes will lead to more. Maybe, just maybe, she can haul the composure she finds at work into the gym with her…

This is the premise for a debut by attorney-turned-novelist Aviva Orenstein. Orenstein writes with verve and wit, and her decision to have an overweight character at the center of her novel practically constitutes a political act. She chats via email with Lilith fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough to discuss the underpinnings of her new book, her legal background and what she hopes will be in store for sassy, smart-mouthed Claire.

YZM: Susie Orbach wrote the landmark book Fat is Feminist Issue in 1978. How do you think the idea in that title relates to Claire?

AO: I think that Claire recognizes and agrees with the assertion that fat-shaming of women raises important feminist concerns. Women preoccupied with their appearance and weight can be distracted from important political, social, and feminist issues. Claire’s intellectual appreciation of that does not always translate into self-confidence or self-acceptance. She struggles against self-criticism and obsessive concern about appearance. Happily, this is an area where she makes some headway over the course of the book.

YZM: Do you think Jewish women have a particularly charged relationship to food and eating?

AO: Women’s issues with food are not uniquely Jewish, but Jews’ use of food for celebration and for healing reinforce both the pleasurable and the painful aspects of food and eating. Women’s cooking is a deep part of Jewish tradition and expression of love, as when Claire makes her Grandmother’s chicken soup when Rob gets the flu. Because Jewish eating is very ritualized via the do’s and don’ts of keeping kosher, eating can feel morally laden and restrictive. Claire affirmatively eats bacon sometimes to be transgressive or to express anger at God. In fact, Claire often eats as a way of tamping down her feelings. The family orientation of eating can sometimes make enjoyment of food fraught, evoking negative family dynamics and unhappy memories of times around the dinner table. These mixtures of pleasure and pain, indulgence and restriction explain the conflicted attitude Jewish women have around food. Throw in pressure to be slim and to engage in self-denial, and one has a recipe for a very screwed up relationship with food and eating.

- 1 Comment

March 21, 2016 by Hanna R. Neier

Fair Labor Lawyer: Bessie Margolin’s Journey from New Orleans Orphanage to Supreme Court Advocate

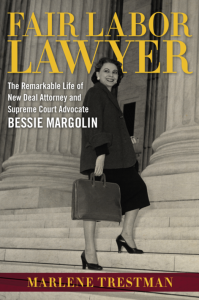

Not every biographer has the keen advantage of having met her subject. Marlene Trestman, author of Fair Labor Lawyer: The Remarkable Life of New Deal Attorney and Supreme Court Advocate Bessie Margolin (LSU Press, March 2016), was lucky enough to not only have known Margolin but also to have been mentored by her.

Not every biographer has the keen advantage of having met her subject. Marlene Trestman, author of Fair Labor Lawyer: The Remarkable Life of New Deal Attorney and Supreme Court Advocate Bessie Margolin (LSU Press, March 2016), was lucky enough to not only have known Margolin but also to have been mentored by her.

From Margolin’s childhood in the New Orleans’ Jewish Orphanage to her Supreme Court advocacy and behind-the-scenes work at the Nuremberg trials, Trestman lets the reader glimpse Margolin’s character, and her sometimes scandalous love affairs which give added dimension to this fascinating historical figure.

Trestman, former Special Assistant to the Maryland Attorney General, is a notable attorney in her own right who was fostered at age 11 by the same Jewish agency that took care of Margolin. Recently, the biographer talked to Hanna R. Neier about Margolin’s struggle with gender inequality, the life of a Jewish orphan in New Orleans, tikkun olam and the Supreme Court.

HRN: Why did you want to write Bessie Margolin’s story?

MT: It’s a bit of a stretch to say I “wanted” to write Bessie Margolin’s story. Instead, as one of the most influential women attorneys of the 20th century, she deserved to have her story written, and I felt I had a duty to find someone who would write it. It took me years before I decided that I could do justice in telling her remarkable story. Margolin and I shared common childhood experiences, albeit separated by 50 years. From 1913 to 1925, she grew up in New Orleans’ Jewish orphanage, which closed in 1946. In the mid-1960s, I became an orphan whose foster care was supervised by the agency that earlier had run the orphanage. We both attended Isidore Newman School, which had been founded to educate Jewish orphans. These shared experiences prompted our meeting, and we stayed in close contact throughout my years in college, law school, and into the start of my career as a government lawyer. She was a generous mentor and powerful role model for me, and we had both received life-changing social services and educational opportunities from two wonderful New Orleans institutions.

- 2 Comments

March 15, 2016 by Betsy Teutsch

My Fair Trade Lady: A Trip to Guatemala to Meet Judaica Creators

Why is Fair Trade a women’s issue? And why, furthermore, is it a Jewish women’s issue?

While women are routinely mocked for shopping ‘til we drop, there is truth in female shopper stereotypes: we are responsible for 85% of household purchases, even of products used by men. How do we Jewish women use our purchasing power for social good, raising our purchases from the merely material to mitzvah-territory?

The fair trade movement marries shopping to social justice, guaranteeing fair, reliable wages, gender equity, healthy working conditions, and environmental stewardship. By spending more to assure that the people who create our products are justly treated and compensated, we are following the edicts of Rambam. This famous scholar ranked tsedakah; buying fair trade is at the top, since it helps the poor escape destitution. When I first explained the concept of fair trade coffee to my son Zach, he pointed out its opposite: “unfair trade”, where workers are squeezed and powerless.

This past February, I traveled to Guatemala with 10 other women and two men on Fair Trade Judaica’s annual trip visiting artisans who, remarkably, create beautiful Judaica. In fact, their Judaica lines have been so well received that the craftswomen are expanding them.

While many Jews have supported Fair Trade through their individual purchasing, Ilana Schatz created the Fair Trade Judaica movement. On a honeymoon trek to Nepal with her husband, David Lindgren, she shopped for a replacement for her worn-out tallit. She met a weaver whose work she loved and commissioned a new prayer shawl.

Ilana Schatz, founder of Fair Trade Judaica. Photo by Betsy Teutsch.

When she put it on back home in Berkeley, Schatz felt suffused by the spiritual connection to her tallit’s creator and the satisfaction of knowing her tallit helped the weaver support herself. Seven years later, Fair Trade Judaica has become a portal for fair trade Jewish ceremonial objects as well as outreach and education in the Jewish community about incorporating fair trade purchasing into our individual and communal practices.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...