by Esther Sperber

The Shadow of Zaha Hadid

Zaha Hadid via Knight Foundation

I was sitting at my office desk, Thursday morning, March 31, multitasking as usual; checking my email, drafting plans for my sister’s apartment renovation in Tel Aviv, logging data into my bookkeeping software, and (I confess) checking Facebook once in a while. I scrolled through the feed of vacation photos, op eds and political comedy when I suddenly caught my breath – Zaha Hadid had died of a heart attack, age 65.

I’ve been thinking about Hadid’s death since its startling appearance in my Facebook feed. Had you asked me on Wednesday who my architectural heroes were, I probably would not have mentioned her name. She was amazing, but my role models are smaller, more approachable, perhaps more like I want to see myself when I grow up. I might have mentioned Carlo Scarpa, whose buildings I insisted on visiting on a recent trip to Verona and Venice. Or maybe I would have noted Jeanne Gang, whose work is both intelligent and poetic. Zaha, I would have said, was too unique and too brilliant. She imagined things no one had ever seen, and she was able to make these fantasies become physical realities. I could not see myself in her.

Nevertheless, I keep thinking about her, staying up late, reading admiring obituaries, snappy stories calling her a “diva” and online posts from young students. If she was not my hero, why does her death matter so much?

I remember the awe I felt when I first encountered her winning entry for the Peak Leisure Club in Hong Kong (1982). I was studying architecture at the Technion in the early 1990s, still busy with an Israeli version of a functional modernism. Hadid’s drawings were anything but functional. The design was a stunning composition of exploding forms, bold colored surfaces soaring from the cliff, projecting a future of spaces that could not yet be build.

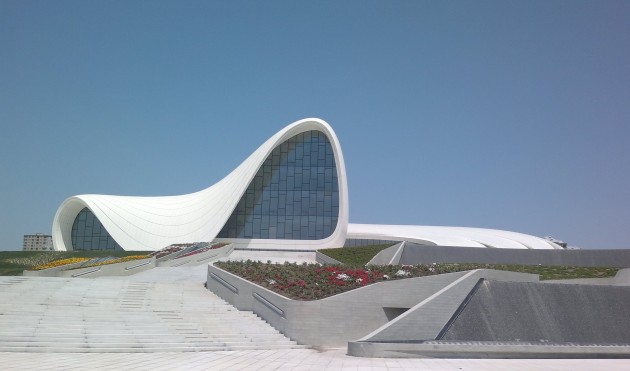

Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre in Baku, Azerbaijan

Later, when I came to New York, I attended her lectures and went to hear her reviewing her students’ studio presentations. By then, it was 1998; the world of design and computers was catching up to her vision and we were all making computer models of curved spaces, soon to be manipulated, optimized and constructed. Hadid was one of the driving forces in the evolution that emancipated buildings from orthogonality, flatness and the ancient distinctions between walls, floors and roofs. In Hadid’s buildings, surfaces were free to fold, curve, twist and bend, creating a continuity of spaces, which –like other rejected binaries–celebrate life on a spectrum.

In the 20 years that passed since I first saw Hadid, much has changed. After years of creating unbuilt work, Hadid had become an international trailblazing architect, with a staff of 400 and innovative, large-scale projects around the globe. She was the first woman to receive the Pritzker Prize (2004), and the first Muslim too. She received the Stirling prize two years in a row (2010, 2011) and she was made Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) in 2012.

So why am I thinking about her so much? Perhaps Hadid’s death is particularly upsetting because, as Thomas de Monchaux wrote in The New Yorker, architects tend to flourish later in life, making Hadid’s death at age 65, with only 10 years of constructed buildings, all the more premature. Or perhaps, as the New York Times article suggested, it was her singular position as the greatest female architect that amplified her death as a personal loss to me as a woman architect.

But alongside my admiration, and slight envy of Zaha Hadid, I hear a small ugly voice whispering in my head. This voice says, “she was too big for life and so she died.” It is true, I admit, that she defied so many social norms, being ambitious, creative and successful, and choosing not to marry or have children. This, the Trump-like-misogynist voice in my head says, was too much; the universe could not maintain this kind of female presence.

I hate this voice and can’t believe it resides within me. How is it possible that after years of thinking, lecturing and writing about women in architecture, questioning the current gender roles, a voice like this still persist and haunts me from within my own mind?

A century after Freud, we accept that we are not masters of our minds, which contain layers of biological and cultural residue. This heritage includes the treasures of creativity and the transcendences of spirituality along with misguided misogyny, cruel racism, and infantile envy, leftover voices of a past that still echo within us. Perhaps, my ugly internal voice resenting Hadid’s success is a reminder that we are still on the journey to women’s equality, and that the structures that need to be changed are internal as well as external.

Healthy mourning is achieved, Freud writes in Mourning and Melancholia, when the deceased loved one is internalized, and becomes part of who we are; in his enigmatic words, “Thus, the shadow of the object fell upon the ego….”

Zaha created complex and magnificent buildings. May the shadows of these objects fall upon us.

Esther Sperber is the founder of the award-winning New York-based firm Studio ST Architects. Born and raised in Jerusalem, she also lectures and writes on architecture and psychoanalysis.