by Hanna R. Neier

Jennifer S. Brown, Author of “Modern Girls,” Talks Mother-Daughter Drama and Choosing Abortion in the 1930s

Dottie’s got a great job in Manhattan. She blows her salary on the latest fashions, escapes to the country with her friends when the city is stifling, and is in love with her boyfriend of three years. Her mother’s a stay-at-home, spends her life pushing her kids to make the most of theirs and dreams of her young political days when life used to mean so much more.

Dottie’s got a great job in Manhattan. She blows her salary on the latest fashions, escapes to the country with her friends when the city is stifling, and is in love with her boyfriend of three years. Her mother’s a stay-at-home, spends her life pushing her kids to make the most of theirs and dreams of her young political days when life used to mean so much more.

It’s a timeless story—could be happening right now. Only it’s happening in 1935. And Dottie’s pregnant. And so is her mom. And neither is very happy about it.

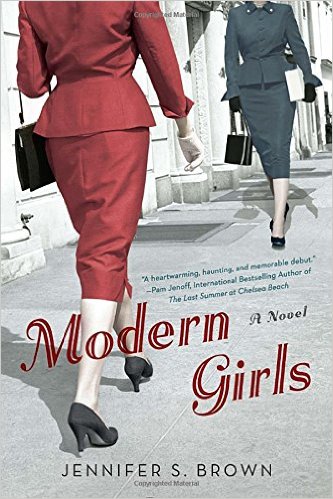

Jennifer S. Brown’s debut novel, Modern Girls (NAL/Penguin, April 5, 2016), handles timeless issues of women’s choices, setting it for added drama in the Jewish world of the Lower East Side before World War II. Lilith sat down with the author to talk about mother-daughter drama, having it all, and what makes a Modern Girl.

HRN: This story has some classic relationship drama—mother-daughter dynamics, lovers who can’t commit. Why set it in Lower East Side, New York in 1935? What was the inspiration?

JSB: When I was pregnant with my first child, I went through the genetic testing common for Ashkenazi Jewish women. I asked my father for our family’s medical history, and I was shocked when he told me, “My grandmother had uterine cancer. They thought it was because of that botched abortion, but I’m pretty sure abortions don’t cause cancer.” I started turning the idea over in my mind, playing with it. Why would a married woman during the Depression not want a child? How are her issues different from an unmarried woman? Starting from there, the novel began to take shape.

Setting Modern Girls in 1935 raised the stakes for my characters. An unmarried pregnant woman in 1935 was shocking and shameful. Not so today, generally speaking. I was curious how that would change the decisions a woman might make.

One other reason to choose the 1930s: The Holocaust so informs our ideas of what it means to be a Jewish person today; what was it like when that aspect of Jewish life didn’t loom over us, but lay threateningly before us?

HRN: The book wrestles with the ways in which motherhood can drastically change the course of a woman’s life—how different would this story be if set in modern times?

JSB: In some ways, the story wouldn’t change at all. The stigma of an unmarried mother has diminished, but the fact remains that motherhood is disruptive, in both positive and negative ways. The myth of having it all has been safely debunked, I believe, and compromises are made when a woman chooses to be a mother. In the novel, a child for Dottie, the daughter, would mean the end of her burgeoning career; for her mother, Rose, it would mean continuing to put her political activism on the back burner. Women today are also forced to make difficult decisions when they choose to become mothers.

HRN: Why narrate from both the mother and daughter point of views?

JSB: I didn’t write Modern Girls with a political agenda, but I did want to explore the idea of unwanted pregnancy from both sides: a woman who is horrified at the idea of terminating the pregnancy and another who thinks it’s the best course of action. Abortion is still a taboo topic in much fiction; I’ve read so many novels in which an unmarried pregnant woman declares she’s prochoice but then quickly dismisses the option of abortion. I wanted to really push the issue. By narrating through both Rose and Dottie, both sides could be fully delved into.

Plus, mother-daughter relationships are always fraught. Add in an unwanted pregnancy and you have real tension.

HRN: Both mother and daughter think of themselves as Modern Girls, yet the generation gap so clearly divides them. Thoughts?

JSB: I love how the idea of “modern” is so fluid and subjective. Every generation thinks it’s more modern (or, in terminology of today, “hipper”) than the previous. I remember my grandmother talking about how old-fashioned her mother was, with her Yiddish and her Old World ways of doing things. My grandmother was fashionable, political and spoke her mind. Yet when compared to my mother, who with two kids earned an MFA in sculpture, my grandmother’s way of life seems antiquated. My own tween children look at me with frustration when I can’t keep up with technology as they can.

Rose considers herself progressive: she doesn’t cover her hair as her mother did, she’s involved in politics, and she can navigate Manhattan. But Dottie just sees a Yiddish-speaking balabusta. Dottie considers herself the epitome of the modern girl, yet when in the high-end Upper East Side, she feels as Old World as her mother. Modernity is a matter of perspective.

HRN: What kind of research did you do to bring the world of Dottie and Rose to life?

JSB: Books were my first source. I devoured books by authors writing in that time period: Anzia Yezierska, Henry Roth, Abraham Cahan, Michael Gold. The collection of letters to the advice column in the Forverts, The Bintel Brief, gave me great insight to the concerns of the time. I referenced history books on both Jewish America (in particular Irving Howe’s World of Our Fathers) and the Depression era. I had great fun with a minor shopping spree on eBay, buying magazines from 1935. I channeled Dottie as I lay on my bed paging through House & Garden, McCall’s, and Cosmopolitan. A glorious day was spent at the New York Public Library reading the Socialist publication New Leader.

My research wasn’t limited to the printed page: I watched movies from the 1930s to get an idea of the speech patterns and fashions; I visited the Tenement Museum in New York to understand how Jewish immigrants lived; I even tried making a kuchen without modern tools, such as my standing mixer, to understand how Rose would have made one.

HRN: There seem to be some unanswered questions at the end of the novel—any plans for a sequel?

JSB: I’m working on another historical novel that is not a sequel. Right now I like the uncertainty of everyone’s future. Both Rose and Dottie, I think, have satisfying ends to their stories. I’ll be intrigued to hear what readers think will happen to them next.