The Lilith Blog

April 23, 2019 by Sharrona Pearl

No, You Can’t Just Use Jewish Wedding Rituals if You’re Not Jewish

My Jewish ritual should not be used for your Pinterest wedding.

I understand the desire to make a wedding unique. It’s pretty much impossible, honestly, but do your best. You want to hold it in an abandoned train station with a farmer theme while everyone sits on water balloons? Gezunteheit. You want your guests to feel transformed, moved by all the little ways your infuse meaning into the moment, to create lasting memories that will stand out amongst all the white dresses and rustic farm settings with wildflower centerpieces?

Go for it.

Just don’t use my (or anyone’s) sacred ritual to make your wedding pop on Instagram.

It’s a thing. I had no idea it was a thing until I read a 2011 Washington Post article entitled “A Jewish Wedding for Two Non-Jews” that recently got widely re-circulated. I wasn’t sure what to expect when I saw the headline; maybe it would tell the story of a couple getting in touch with the Jewish roots or finding the religion as adults and using the wedding as a way to honor their personal journeys. Maybe (though it seemed unlikely) it would be a thoughtful narrative about how an interfaith family was struggling to incorporate their two traditions in a way that respected them both. Maybe the two non-Jews in question were not the bride and groom, but other people involved in the ceremony and celebration.

Nope. The article was literally about how two non-Jews decided to make their wedding stand out by having a Jewish ceremony, complete with chuppah, ketubah, breaking of the glass and – wait for it – the ritually unnecessary but photo friendly Rabbi as officiant. Until I read the article, I didn’t even know about these kinds of weddings, but it turns out that this article isn’t an anomaly: non-Jewish people do borrow Jewish rituals for their weddings.

I was so angry. I actually shocked myself by how angry I was. It felt, simply, like the grossest violation of history, tradition, and the ties that bind a community and a religion together.

I know that debates about cultural appropriation are complicated. I know that there is a meaningful difference between appropriation and appreciation. I know that it can be hard in some cases to point to clear origins in culture and that culture itself is constantly shifting and changing precisely because of the interplay of traditions with history and practice. But there’s a huge difference between, say, white women getting praised for wearing cornrows, a style that women of color have been discriminated against for using on the one hand, and all the people of New York enjoying a good bagel on the other.

The Jewish wedding thing is the bad kind, though. The chuppah isn’t just a canopy, although there are some beautiful ones out there. Breaking the glass isn’t just a chance for people to hear a loud bang and shout mazel tov. The ketubah isn’t just a piece of artwork to be framed on your wall as a reminder of the day, though you can get all kinds of imitation Chagall styles that document the rights of the bride and how many goats she is worth.

All these pieces are links in a long chain that connect the Jewish people across time, across space, and yes—across struggle. They are, in part, designed to emphasize how the marriage celebration is a communal event that isn’t just about the bride and groom but their place amongst the Jewish people. Our wedding rituals, while beautiful, aren’t about photo ops and guest reactions. They are about our future, but they are just as much about our past. And they are not static: they have changed, and grown, and diverged across our wonderful and living religion, and they will continue to evolve. But this is not their next stage.

These traditions are ours, and that actually really matters. Others don’t get to just borrow them on a whim. Of course, this couple did, and they are certainly within their rights to do so—but I absolutely have the right to say that it is wrong. These weddings don’t seemingly affect me in any way, nor do they seemingly pose a tangible threat to the safety of the Jewish people, the sanctity of Jewish ritual, or the rights of Jews to practice their religion freely. Some could argue that this wedding was an homage to our way of doing weddings, and we should be flattered and even encouraging of this (ugh) trend.

Nope. Not flattered. Not encouraging. And, frankly, not agreeing that it isn’t a threat. When ritual and religious practice become a matter of style, they become a matter of negotiation. They become a matter of taste. They can be evaluated by the whims of others, and they can be encouraged or repressed by those same tastes.

When religion becomes a trend, it can stop trending. Violently, or otherwise. There’s a big – and meaningful – difference between someone who things my taste is bad, and someone who thinks my religion is bad. There’s a big difference between someone who wants to appropriate my taste (enjoy!) and someone who wants to appropriate my religion. And there’s a big difference between trying to change my taste and someone trying to change my religion.

Maybe find a scenic railway station instead.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.

- No Comments

April 22, 2019 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

A Novel Bends Time at the Onset of the Holocaust

A talented young female musician, the bookselling man who loves her and a quasi-magical way to escape the rising Nazi horror in Germany are the key elements in Jillian Cantor’s latest novel, In Another Time.

Below she chats with Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about how she crafted this original and compelling story that asks whether it’s really possible to escape the horrors of history.

- 1 Comment

April 22, 2019 by Rebecca Katz

Anxiety Nights II

Anxiety has been a familiar companion in my life. Starting in high school, I have used tv as an effective and addictive coping mechanism for anxiety. Bedtime is a particular battleground for my anxious mind.

I have to learn how to self-soothe without TV.

(Previously: “”Hello, Anxiety, My Old Friend” and “Anxiety Nights I“)

- No Comments

April 17, 2019 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Golden Girls of the Silver Screen

Well told and illustrated with charm, Renegade Women is a coffee table book for our feminist pop cultural age. It offers more than 60 informative and whimsically illustrated portraits of female movers and shakers in the entertainment field.

Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough chats with author Elizabeth Weitzman about the importance of highlighting their impressive accomplishments.

- No Comments

April 17, 2019 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

The Story of a Storyteller

Longtime Lilith readers may remember Miryam Sivan’s name; her story Roadkill appeared in the magazine in 2003 and City of Refuge was featured in 2011.

Now she’s back with her debut novel, Make It Concrete, which is set in contemporary Israel and follows a woman who transcribes Holocaust stories. Sivan talks to fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about how the past shapes and even defines the present.

- No Comments

April 16, 2019 by Rebecca Katz

Moments My Bubbe Would Hate, Part 1: My Wedding

In early 2016, my maternal grandmother, Esther, passed away in her 100th year. Her grandchildren called her “Bubbe,” Yiddish for grandmother. She was a force in life- matriarch of our family, a proud rebbetzin and social worker—and remains a force in death. During significant life moments or times of transition, I often conjure her memory. I think about how she’d vocally disagree with most of my decisions and the pleasure she’d get from explaining why I’m wrong. I know she was proud of me and truly believed that, if only I listened to her, my life would be significantly better.

- No Comments

April 16, 2019 by Justine Orlovsky-Schnitzler

A Secular Feminist Embraces Shabbat

The first time I observed Shabbat according to the laws of the Torah, it snowed in the desert.

There was a certain degree of irony there—that hell had frozen over, and now I was celebrating the Sabbath in the home of an Orthodox friend.

I was anxious in the hours leading up to sundown, watching large, wet snowflakes blanket the cactus in my front yard. It was the kind of anxiety that comes with imposter syndrome—all my Jewish celebrations had thus far involved a wide margin of error. My partner and I didn’t worry much about saying all the right prayers in the right order, because our practices were secular expressions of our shared culture, not an expression of religious devotion.

- No Comments

April 15, 2019 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

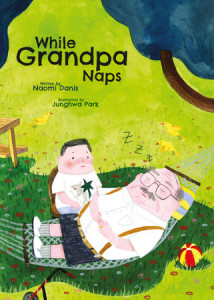

From “I Hate Everyone” to “While Grandpa Naps,” Naomi Danis on Her Fiction for Young Readers

Naomi Danis is Lilith’s resident angel/soother of souls/bridge over troubled waters. She combines a practical-get-it-done attitude with an uncommon amount of kindness and empathy and she is much-loved within the office and beyond.

Danis is also an accomplished author of several well-received picture books and as she prepares to launch her latest, While Grandpa Naps, illustrated by Junghwa Park, she talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the way she keeps so many balls spinning in the air with such effortless grace.

Danis is also an accomplished author of several well-received picture books and as she prepares to launch her latest, While Grandpa Naps, illustrated by Junghwa Park, she talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the way she keeps so many balls spinning in the air with such effortless grace.

YZM: Tell us when you started working at Lilith and a little bit about what the job has been like.

ND: I started working at Lilith in 1988, after nine years at home raising three children, during which time I began seriously writing for kids. I had trained as an early childhood teacher, also have an MA in English, but learned from a friend at my Forest Hills synagogue who did grant writing that Lilith was looking for someone. The position turned out to be administrator, and I really wanted to be called something like assistant editor, but two friends in publishing I consulted said if you like the people, take the job. I still love it after all these years, and feel very lucky and grateful every day. I have the kindest, smartest, funniest, most caring, talented, inspiring and encouraging colleagues.

- No Comments

April 12, 2019 by admin

A Film About Faith… Starring Jewish Men, Men and More Men

Comparing practices across religions can provide insights into customs and beliefs, and highlight our shared humanity. I approached the film “Sacred,” recently shown on PBS, expecting to be enlightened. A feature length documentary, it’s been shown at more than 75 film festivals around the world, had a week-long run at the Rubin Museum in NYC and numerous screenings at congregations, theaters and universities.

In many ways, “Sacred” does not disappoint. A travelogue of religious practices in over 25 countries, the film is a visually rich mosaic. The diverse and pluralistic material is treated with respect and even reverence, and the overall message is solid: there are a variety of ways to approach the spiritual, that there’s no one answer and no monopoly on truth.

- No Comments

April 11, 2019 by admin

Can Leviticus’ Purity Laws Help Us Understand #MeToo?

The poet Galit Hasan-Rokem wrote the following poem entitled “This Child Inside Me”:

This child inside me

Sorts my existence into elements:

Blood and urine

Calcium and iron.

In my sleep I am a quarry

Where rare treasures are suddenly found.

Blood and urine, calcium and iron. The fluid and elements that, in part, make up the physical constitution of a human body. This is, in part, the focus of our Torah portion earlier this month, called Parashat Tazria—which is always a confounding one for the bar or bat mitzvah student. The particular section of the Torah that we read at this time of year addresses issues of ritual purity. Some of those considerations include menstruation and childbirth. This part of the Torah is, indeed, a bar or bat mitzvah student’s worst nightmare. Every year, one or two innocent and unknowing soon-to-be 13 year old finds themselves forced to find relevant meaning in rules concerning nocturnal seminal emissions and afterbirth. Meanwhile their more fortunate classmates with simchas that land in the fall are assigned Noah’s ark and the Garden of Eden.

Leviticus builds character.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...