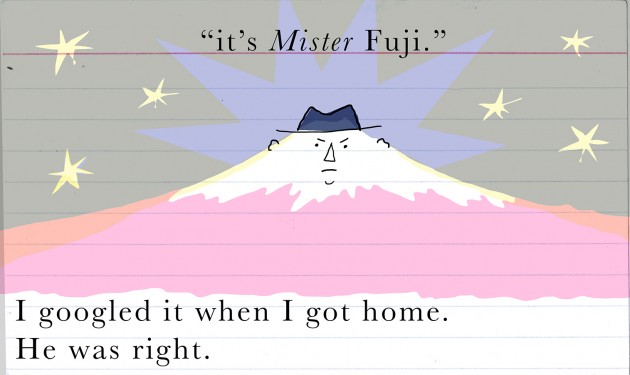

July 25, 2013 by Liana Finck

When in Japan…

Liana Finck received a Fulbright Fellowship and a Six Points Fellowship for Emerging Jewish Artists. She is finishing a graphic novel, forthcoming from Ecco Press, based on the Bintel Brief, a beloved Yiddish advice column that was published in the Forward newspaper beginning in 1906.

- No Comments

July 24, 2013 by Chanel Dubofsky

Part 2: Inheriting Our Mother’s Fears

Read Part 1, On Not Knowing, here.

I always think about my mother when I’m on an airplane, because she was terrified of them. The first time I was ever on a plane was when I was eight years old, and I flew alone from where my aunt lived in Pennsylvania to Massachusetts, where I lived. On that first-ever flight, I felt like I was just sitting in a room. I had no concept of anything short of invincibility.

On a daily basis, the things I don’t know about my mother don’t necessarily impact me. Occasionally, there are awkward questions. It’s hard to respond with brevity that’s not also brutal when people ask me where my parents live, what they do, why I’m not spending holidays or vacations with them. Sometimes, though, like when I’m on airplane, or in another city, or doing any number of things that she may have wanted to do but never did, I think about not just the things I don’t know, but the things I do.

From my mother, I learned fear. Not healthy skepticism or gentle caution, but fear, and paranoia, and the idea that it was perpetually dangerous to ever be too comfortable, to push too hard, to go too far. One should never trust people, or stop looking over one’s shoulder. Intellectually, I understand where this comes from—she was surprised by thyroid cancer at fifteen, struggled with infertility (or so I’m told), then cancer again and divorce, both while raising a child. It seems logical to me that she would think nothing was safe, and at the same time, the most pervasive feeling I have these days in regard to her is resentment and the perpetual question: What do you think of what I’m doing right now?

I have this picture of my mother as someone whose life was never within her control, for whom bad luck was the norm, and had constructed an identity based on victimization. If she were alive now, what would her advice be to me for my life?

I inherited my mother’s fear of flying. As soon as I was old enough to realize that there were things to be afraid of while 35,000 feet in the air, I was afraid. Whatever the logic was to the safety of flying, I managed to be unconvinced by it. The thought of getting on a plane filled me with such complete terror that I cancelled a trip to Israel in my third year of college. (This was shortly after my mother’s death, and my grandmother, alarmed by the thought of me leaving the country or even the state, did not attempt to talk me into going.) I didn’t actually manage to get on a plane successfully until I was 23, after realizing that the alternative was never leaving the country. I wanted desperately to travel, but what ultimately pushed me onto that plane was knowing that my mother had not, because of circumstances, and also because of a fear that I had assimilated but didn’t want anymore.

The older I get, the more questions I have for my mother. Did she think fear would protect me? As far as I can see, it did not protect her from anything except living her life, but there is maybe a different explanation. If I can’t know what it is, perhaps the best thing I can do for myself is to make it up.

- No Comments

July 23, 2013 by Sarah M. Seltzer

Our Princesses, Ourselves?

Thoughts on Jappiness

The first time I ever heard the term “JAP” was at a spartan, secular camp in Maine that, like many of its kind, had a fair share of Jewish campers. My cabinmates and I were lodging a complaint about three older campers who came from a notably Jewish Northeastern suburb. Our tormentors had braces, and their features sat awkwardly on their faces in the way all features do in adolescence. They were like us, yet they were not, because they had chutzpah enough in bikini tops to crown themselves queens of the camp social scene. They turned the announcements, the open mics, the DJing, the talent shows into a staging ground for their own inside jokes. “Those girls can be really jappy,” the director receiving the complaints told us sympathetically. He was a member of the tribe, yes, but I had been convinced he was going to say snobby or cliquey or mean, not, you know, Jewish.

Then, less than six months later, I started seventh grade at a prep school in New York City, and I got it. JAP wasn’t just about ethnicity—it described an entire modus operandi. We used “JAP” in the halls of Horace Mann to criticize the popular girls and issue warnings about creeping conformity. “You’re wearing that? I never thought you’d be such a JAP.” JAP indicated in its broad sweep the ostentatiously wealthy—and also all those who were self-assured enough to run with them, or ride with them in their BMWs as the case often was. When we made use of the shorthand, it targeted the handful of non-Jews, including black girls, Indian girls, and WASPs, who hung out with impunity in the ranks of the “Jappy group.”

I probably uttered the word “Jap” five times a day for six years, only misunderstood when I ventured out of New York City and people assumed I was being viciously racist towards Japanese people. No, I explained, being provincial in the guise of sophisticated: Jewish American Princesses. You know what I’m talking about? Like: Kate Spade, nose jobs, drivers. JAPs.

- 4 Comments

July 18, 2013 by Liz Lawler

Homeschooling While Orthodox

I grew up peripherally aware of parochial schools. But most of what I knew concerned Catholic schools, land of the wealthy or otherwise unfit for public school. The Yeshiva system? That was an exotic new world I discovered post-conversion, along with gefilte-fish and dreidels. It is still largely mysterious to me, largely because it seems like the stuff more Orthodox Jews are made of. It is, unquestionably, training ground for a strong Jewish identity. In the mission statements of any yeshiva you pull up, you will find a reference to Torah, to heritage, often to Israel. Whether or not you feel like the educational standards are up to snuff, you can count on your kid identifying as a Jew upon graduation. But what goes into this machine? And what of those who don’t take this path? There is in fact, a small and growing contingent of Jewish families who have chosen to step outside of formal education.

I grew up peripherally aware of parochial schools. But most of what I knew concerned Catholic schools, land of the wealthy or otherwise unfit for public school. The Yeshiva system? That was an exotic new world I discovered post-conversion, along with gefilte-fish and dreidels. It is still largely mysterious to me, largely because it seems like the stuff more Orthodox Jews are made of. It is, unquestionably, training ground for a strong Jewish identity. In the mission statements of any yeshiva you pull up, you will find a reference to Torah, to heritage, often to Israel. Whether or not you feel like the educational standards are up to snuff, you can count on your kid identifying as a Jew upon graduation. But what goes into this machine? And what of those who don’t take this path? There is in fact, a small and growing contingent of Jewish families who have chosen to step outside of formal education.

As I mentioned in my last post, I have chosen to homeschool my son. But this is a minor rebellion on my part; I’m not really going against the community grain. For a Jewish family living in Orthodox Brooklyn, homeschooling represents a clear departure from the very orthodoxy they have been raised to respect. How can they make this choice and still balance their obligations to community and culture?

- No Comments

July 17, 2013 by Chanel Dubofsky

On Not Knowing

Information about my mother can be divided into three categories: things I know, things I don’t know, and things I have been told. Here’s a clue about where this piece might be going: the “things I know” are few.

Here’s what I do know: My mother was born in Los Angeles. When she was 15, she had thyroid cancer. Her thyroid was removed. She took synthetic thyroid for the rest of her life. I remember seeing that pill bottle every day. She graduated high school in 1963. (I have her graduation picture.) I was born when she was 33. When she was 40, she was diagnosed with breast cancer. My parents divorced when I was 7.

My mother died when she was 53 and I was 19. Her death was long in coming. It had been a steady march to the end since my senior year of high school when her breast cancer, which she’d had in various spates since I was very small, metastasized.

I have few memories of my mother that are not somehow tinged with guilt, or fear, or resentment, the result of years of acting like her parent, performing emotional caretaking, and trying (and failing) to be just a normal kid. My grandmother, who lived with my mother and me, stepped back while I accompanied my mother to doctor’s appointments.

Around the time that my mother died, I started to notice a change in the way my peers were relating to their parents. They were excited when parents came up to camp on weekends. They were learning things about each other—romantic disasters, pre kid shenanigans. Parents were becoming people, fleshed-out humans with personalities.

- 1 Comment

July 16, 2013 by Shayna Goodman

Friend of My Youth Group

image via mockstar

I hadn’t seen Ari for seven years but I remembered him well. Actually I remembered him in nostalgic and probably inaccurate detail. I remembered us on a youth group tour of Israel, sitting on lawn chairs outside the hostel in Jerusalem. I remembered that Ari was optimistic, athletic, with dark curly hair. On long bus rides we fell asleep listening to Coldplay (very alternative and cool) on his iPod. This was a simpler time: we shared one electronic device between the two of us—one set of headphones. We had only 300 songs to last us through our leisure-trek through the desert.

For seven years Ari and I exchanged occasional emails. I didn’t think I’d ever see him again. We had passed the point where it was comfortable to travel for the purpose of seeing each other. But circumstances lined up and seven years after we’d parted at Newark Airport, I was on my way to see him. I was not headed to Israel, where I had fantasized our reunion would take place, but to gray, rainy Seattle. At seventeen I had gone to sleep missing Ari and tearfully listening to Coldplay. At 24 there were other men to mourn and other sources of reminiscing. But I still felt that this Seattle visit was of cosmic importance.

Ari, who was shorter than I remembered, came to meet me in the lobby of his building like this was no big deal. He showed me his small, impeccably neat, one-bedroom apartment. I had not remembered him being so neat or having all his clothing folded so perfectly and the shampoo bottles in the bathroom lined up so accurately in height order. I noticed a copy of Alice Munro’s “Friend of my Youth” sitting on the coffee table, which I hoped was coincidental. I was somehow surprised to find that our romantic chemistry was gone.

It felt awkward so we went for a drink at a bar down the street. Discussing the old days and getting a whiskey felt like acting out a scene from a Saul Bellow novel I once read about an aging Chicago native in Belarus who happens upon his childhood friend. It felt silly to reminisce about seven years prior.

There were a lot of do-you-remember questions like “Do you remember sitting on the balcony at the hostel in Jerusalem?” or “Do you remember the Russian kid, Vladimir, who didn’t integrate with the Skokie kids so well?” or “Do you remember when we had to do that reenactment of the Palmach missions on the beach near Haifa? And you were on the European refugee team and I was a British officer?”

- No Comments

July 15, 2013 by Sonia Isard

Lamentations for Trayvon Martin

In preparation for tonight’s Tisha B’av services, I’ve been re-reading Eykha (Lamentations)—the text we chant each year to mourn and commemorate the destructions of the First and Second Temples in Jerusalem. It’s one of my favorites of the canonical texts—there’s always something I’ve never noticed before, some new line jumps out and gets stuck in my head. The poetry is dramatic and compelling, rich with imagery and shading.

Reading over my JPS translation this weekend, one eye on my book and one eye on my Twitter feed, it was almost too easy to read the Trayvon Martin case into the text. Too easy to feel that, in addition to commemorating the Temples of old, we should be in mourning for the justice system of today.

I saw Trayvon Martin in the lines about suffering at the hands of unjust tormentors.

My foes have snared me like a bird,

Without any cause.

They have ended my life in a pit

And cast stones at me.

I read the failure of our courts in the tales of Jerusalem’s crimes and punishments.

Jerusalem has greatly sinned,

Therefore she is become a mockery.

All who admired her despise her,

For they have seen her disgraced;

And she can only sigh

And shrink back

I heard echoes of my own disillusionment in our justice system.

To deny a man his rights

In the presence of the Most High

To wrong a man in his cause—

This the Lord does not choose.

In anger and in sadness, I’ll be thinking about Trayvon tonight. Anger because I have witnessed unabashed disregard for the way racism continues to permeate our American systems. Deep sadness because Trayvon died so young, amidst such venom. Fury because George Zimmerman killed a young black man and was acquitted. Our American justice system endorsed this injustice.

My children are forlorn,

For the foe has prevailed.

Sonia Isard is Lilith’s associate editor.

- 3 Comments

July 11, 2013 by Nathalie Michelle Gorman

My Forbidden (Mechitza) Love Story

image via meaduva

I grew up Reform in a synagogue that “sat mixed.” In fact, many of the members of my community wouldn’t have immediately understood the phrase “sitting mixed,” because as far as we were concerned, that’s how normal, modern people sat in synagogue—men and women together. Anything else would have been considered at best exotically retrograde and at worst outright oppressive. So it came as something of a surprise to me when, as a college student, I started davening in an Orthodox minyan and fell in love—with the mechitza.

It happened like this: I was interested in learning more about traditional Judaism, and I liked the students in the Orthodox minyan a lot, so I started going to their services on Fridays. And going to their services meant a mechitza.

I thought that sitting in the women’s section would require me to be really brave, because I was convinced doing so would evoke acute discomfort and a sense of horrible degradation. Instead, from the first moment I took my place on the left side of that wood and plexiglass screen in the fluorescent-lit basement room where we met every week, I felt something completely unexpected: Peace.

- 2 Comments

July 10, 2013 by Wendy Wisner

The Poetry of Birthing at Home

In light of recent news about the high cost of giving birth in the United States, let’s hear from the authors of Home/Birth: A Poemic, which was reviewed in Lilith’s Fall 2011 issue.

Wendy Wisner asks co-authors Rachel Zucker and Arielle Greenberg about the book and their experiences.

Wendy Wisner: Home/Birth: A Poemic was published in 2011, and you both have been reading from it at venues throughout the country. The idea of birthing at home is troublesome and frightening to many people. How have readers/audiences reacted to the book? Has anything surprised you?

Arielle Greenberg: My sense is that most of the people who’ve come so far are already interested in the subject of homebirth, if not rabid about it. So at these readings, there’s a palpable sense of relief, that the unpopular opinion we hold and put forth in this book—that the current birthing system is disempowering and potentially harmful to women and babies, and that women deserve to experience their births in a very different way—has been spoken aloud, and that this community of mothers and midwives and other birth workers who feel this way exist, are visible.

But of course not everyone who has come to our readings has been of this mind, and we’ve been grateful that at each Q&A we’ve held, there have been folks who have questioned and challenged our statements, people who had very different experiences or feelings about their own births or choices. Those disagreements and the discussions that have followed have been some of the most meaningful moments for us.

Another gratifying response has been from people we didn’t expect would read the book: younger women who have not yet decided if or how they want to give birth, poetry readers who would not normally read a book about birth. We’ve heard from people who have changed their minds because of reading our book: changed their minds about how they want to plan their next birth, changed their minds about whether they even want to give birth at all. And this is extremely surprising and extremely gratifying.

Wendy: In the book, Rachel mentions her connection to Leah and Rachel from the Bible, and the special significance of her third child’s name, Judah. How have your Jewish identities influenced your perceptions of birthing, and of women’s relationships to their reproductive cycles?

Rachel Zucker: I grew up in a non-observant home but went to yeshiva from first through eighth grade. I was always interested in the bible stories and midrash and in the study of Talmud, but most of my youth was spent rejecting observant Judaism because I felt it was sexist and patriarchal. I resented the fact that there were different expectations and requirements for men and women and that women were treated as lesser than men. I am still not an observant Jew by any means but my feelings about Judaism have shifted. This shift began, really, during my first pregnancy. I remember being flummoxed as a pregnant feminist about how to make sense of how different I felt, how separate, how vulnerable and strong at once. After years of either being pregnant or nursing I began to feel that it did make sense that I should have different responsibilities and expectations than men had. I had to figure out how to accept this while still maintaining an egalitarian relationship with my husband.

- 3 Comments

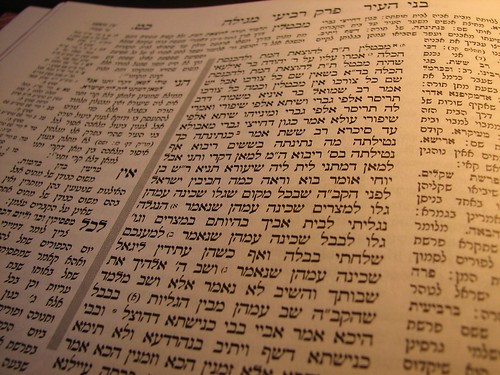

July 9, 2013 by Dasi Fruchter

Can We Speak for Ourselves?

Image via gerardmontigny

I want to paint you a picture of my Yeshiva: Yeshivat Maharat. Piles of giant books are stacked on the table like precarious dominoes, and pens and laptops litter the table. There is a steady hum of learning with the occasional burst of “And Abaye says what?!” As it draws close to 3:30, when it comes time for the instructor to review the holy material with us, we take notes furiously and listen.

While, like in many parallel Orthodox Yeshivot, we struggle with understanding Halachic (Jewish law) nuances between great Talmudic sages, we also battle with the very nature of the text itself. There we are, day in and day out, a group of feminist scholars and leaders, in a movement seeking to change the gender landscape of Orthodox Jewish leadership. Yet we sit at our tables in front of books where the voices of women barely appear. When they do, it is certainly not as serious partners in the development of the Halachic discourse.

So we have a jar. In this jar we put a quarter, or a dollar, or whatever seems appropriate when a woman’s voice seems egregiously absent from a conversation in the text. For example, you can walk into our classroom one afternoon as we explore passages where Rabbis discuss the nature of what was likely the uterus. One Rabbi proposes that it resembles a bag of coins with an opening at the top. No, another Rabbi exclaims, what about a home with a door?

You’ll certainly find me tossing quarters into the jar during that conversation.

This summer, I’m exploring “menstrual purity” laws, and it is in these texts that I feel particularly excluded from the conversation. This past week, I was sitting at my desk late at night, flipping through a more modern book on laws for married women around their periods. In the book, I marked the pages where the author wrote “Ask a Rabbi,” so that I could understand areas of the law about which I will eventually be consulted on. I was disturbed, however, when one paragraph advised the woman reading the book by telling her that if she was uncomfortable showing her stained undergarments or cloths to her male rabbi, she should give them to her husband to bring to the Rabbi for her. I shook my head with a familiar frustration. Here we go again, excluding women from the process.

- 25 Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...