by Dasi Fruchter

Can We Speak for Ourselves?

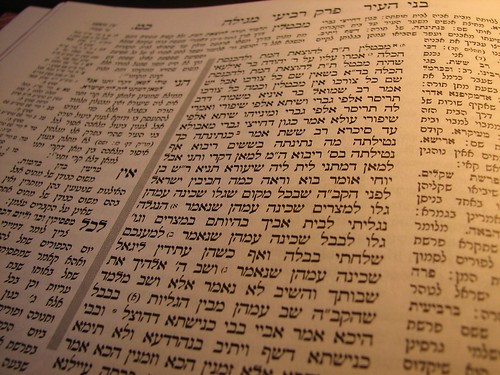

Image via gerardmontigny

I want to paint you a picture of my Yeshiva: Yeshivat Maharat. Piles of giant books are stacked on the table like precarious dominoes, and pens and laptops litter the table. There is a steady hum of learning with the occasional burst of “And Abaye says what?!” As it draws close to 3:30, when it comes time for the instructor to review the holy material with us, we take notes furiously and listen.

While, like in many parallel Orthodox Yeshivot, we struggle with understanding Halachic (Jewish law) nuances between great Talmudic sages, we also battle with the very nature of the text itself. There we are, day in and day out, a group of feminist scholars and leaders, in a movement seeking to change the gender landscape of Orthodox Jewish leadership. Yet we sit at our tables in front of books where the voices of women barely appear. When they do, it is certainly not as serious partners in the development of the Halachic discourse.

So we have a jar. In this jar we put a quarter, or a dollar, or whatever seems appropriate when a woman’s voice seems egregiously absent from a conversation in the text. For example, you can walk into our classroom one afternoon as we explore passages where Rabbis discuss the nature of what was likely the uterus. One Rabbi proposes that it resembles a bag of coins with an opening at the top. No, another Rabbi exclaims, what about a home with a door?

You’ll certainly find me tossing quarters into the jar during that conversation.

This summer, I’m exploring “menstrual purity” laws, and it is in these texts that I feel particularly excluded from the conversation. This past week, I was sitting at my desk late at night, flipping through a more modern book on laws for married women around their periods. In the book, I marked the pages where the author wrote “Ask a Rabbi,” so that I could understand areas of the law about which I will eventually be consulted on. I was disturbed, however, when one paragraph advised the woman reading the book by telling her that if she was uncomfortable showing her stained undergarments or cloths to her male rabbi, she should give them to her husband to bring to the Rabbi for her. I shook my head with a familiar frustration. Here we go again, excluding women from the process. Right after I put the post it note in that place in the book, however, I looked up and was reminded that Rabbinic Judaism wasn’t the only place where a woman’s voice was amplified through a man’s — none of this is ancient history. It was the evening when Texas State Senator Wendy Davis embarked on an incredibly long and historic filibuster journey to aid the defeat of a bill that sought to cut access to abortion services in Texas. I happened to notice that, at around midnight, Senator Davis was whispering in the ear of a man as he repeated what she said aloud. Now this moment was not a particularly significant political moment in and of itself, but this dramatic moment in the political struggle for abortion rights came to symbolize just what I had been thinking about—allowing women to speak for themselves, instead of others speaking for them. As I watched organizations of Jewish women multiply on Twitter in their support of Davis as the evening continued, I was reminded of this very struggle.

Here is another layer: I recognize that it is sometimes necessary for men to speak up in partnership with women–as allies–in order to shift unequal power dynamics and gain additional seats at the table for women, particularly in the Jewish community. These men are our colleagues at parallel rabbinical institutions who tell potential employers to hire women in their stead. They are the Rabbis who go out of their way seek to out women’s voices in Halachic decisions. They are the scholars who have signed on to the AWP (Advancing Women Professionals and the Jewish Community) pledge and have refused to present on panels where no women are represented. These are men aware of the unequal power and who seek to make change through their actions.

I want to return to our male-dominated texts for a moment. Though I do love to reflect, I’m also an action-oriented gal. With my heightened awareness of this pattern–those who are disenfranchised having others speak for them instead of them speaking for themselves–I think about how women engaged in the Halachic system can be active partners instead of just swallowing the texts and bottling up frustration. One day, due to the efforts of some amazing feminists and change-makers, women—serious scholars of Jewish law–will be in conversation will contemporary male Rabbis.

In the meantime, however, there is no reason one can’t teach traditional Jewish law while actively setting a new table, where the seats offered are much more diverse, and include women and other traditionally disempowered groups in Jewish thought. We have new institutions–Yeshivat Maharat included, with Torah-observant women ready and excited to exercise leadership. It’s time not to recreate the same oppressive system that was there before, but to create something new and beautiful. Though very different, I also think of the United States Government, founded on patriarchal principles. Change-makers help the original structure evolve slowly over the years. There are courageous risk-taking women in the world like Senator Davis who are making this happen–by recognizing existing texts and structures but also using them to open and start new conversations.

In the Orthodox feminist world, this is the work myself and my colleagues do when they teach Kallah Classes (pre-wedding classes) to couples that are sex-positive and body-positive. This is the work that community Mikvaot like ImmerseNYC are doing to revive the practice of the monthly ritual immersion after one’s menstrual cycle. It’s the same Halacha, but a refusal to just repeat it verbatim. It’s a drive to bring a different voice to the table and to the Halachic and cultural evolution.

Specifically in the Orthodox realm, I encourage us, as Jewish women, to constantly evaluate where we are in that process. Where are our male allies? Who is organizing around institutional power for women in the Jewish community? Are we taking rituals crafted by men and making them uniquely our own? Can we have a relationship to text that we struggle with as our genuine selves while still being true to Jewish law?

It’s not hard to imagine that the daughters of Zelapchad did the very same thing. These five sisters in the Bible story came before Moses to make the case for a woman’s right to land in the absence of a male heir. These women were a part of the community, and they took action to stand up for inclusion.

Thinking back to the picture of our Yeshiva, the good old “Jar” sitting among the stacks of books could be terribly disempowering. But it doesn’t depress me, because we are there, as a community of women working actively to increase the variety of voices in the Orthodox community. I know that these women will eventually participate in broad Halakhic discourses.

But now, when I look at the Jar and my God-fearing colleagues as the boom of my teacher’s voice echoes through the room, I smile softly. I love what we’re doing.

Dasi Fruchter is a student at Yeshivat Maharat and NYU Wagner. She spends most of her time doing faith-based activism, Orthodox feminist organizing, and hosting delicious, extravagant Shabbat meals.