by Wendy Wisner

The Poetry of Birthing at Home

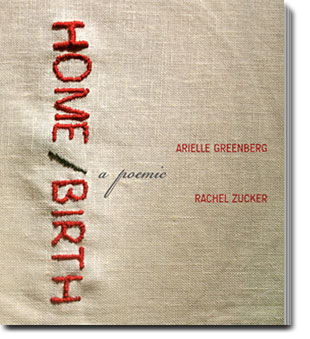

In light of recent news about the high cost of giving birth in the United States, let’s hear from the authors of Home/Birth: A Poemic, which was reviewed in Lilith’s Fall 2011 issue.

Wendy Wisner asks co-authors Rachel Zucker and Arielle Greenberg about the book and their experiences.

Wendy Wisner: Home/Birth: A Poemic was published in 2011, and you both have been reading from it at venues throughout the country. The idea of birthing at home is troublesome and frightening to many people. How have readers/audiences reacted to the book? Has anything surprised you?

Arielle Greenberg: My sense is that most of the people who’ve come so far are already interested in the subject of homebirth, if not rabid about it. So at these readings, there’s a palpable sense of relief, that the unpopular opinion we hold and put forth in this book—that the current birthing system is disempowering and potentially harmful to women and babies, and that women deserve to experience their births in a very different way—has been spoken aloud, and that this community of mothers and midwives and other birth workers who feel this way exist, are visible.

But of course not everyone who has come to our readings has been of this mind, and we’ve been grateful that at each Q&A we’ve held, there have been folks who have questioned and challenged our statements, people who had very different experiences or feelings about their own births or choices. Those disagreements and the discussions that have followed have been some of the most meaningful moments for us.

Another gratifying response has been from people we didn’t expect would read the book: younger women who have not yet decided if or how they want to give birth, poetry readers who would not normally read a book about birth. We’ve heard from people who have changed their minds because of reading our book: changed their minds about how they want to plan their next birth, changed their minds about whether they even want to give birth at all. And this is extremely surprising and extremely gratifying.

Wendy: In the book, Rachel mentions her connection to Leah and Rachel from the Bible, and the special significance of her third child’s name, Judah. How have your Jewish identities influenced your perceptions of birthing, and of women’s relationships to their reproductive cycles?

Rachel Zucker: I grew up in a non-observant home but went to yeshiva from first through eighth grade. I was always interested in the bible stories and midrash and in the study of Talmud, but most of my youth was spent rejecting observant Judaism because I felt it was sexist and patriarchal. I resented the fact that there were different expectations and requirements for men and women and that women were treated as lesser than men. I am still not an observant Jew by any means but my feelings about Judaism have shifted. This shift began, really, during my first pregnancy. I remember being flummoxed as a pregnant feminist about how to make sense of how different I felt, how separate, how vulnerable and strong at once. After years of either being pregnant or nursing I began to feel that it did make sense that I should have different responsibilities and expectations than men had. I had to figure out how to accept this while still maintaining an egalitarian relationship with my husband.Arielle: I will just chime in here to say that Rachel and I have similar backgrounds in this regard, except that I grew up even more deeply in the fold and went further away from it: I, too, went to Hebrew day school from first to eighth grade, and am likewise well-versed in Jewish text and tradition. And, I, too, questioned how feminism and religious Judaism could work together: my mother, for whom this was a life-long struggle, raised me to think about these issues. But unlike Rachel, I was brought up in an observant, Modern Orthodox home, and much of my extended family is Orthodox. And also unlike Rachel, who married a Jewish guy and lives in, one could argue, the most Jewish diasporic neighborhood in the world, I married a non-Jew (a WASP, in fact) and now live in distinctly un-ethnic rural Maine. But—once again, like Rachel!—becoming a mother myself shifted my feelings around Judaism. I dare say that being in an interfaith marriage and living in a place with minimal Jewish community has been good for my sense of commitment to ritual and practice: in the life I’ve chosen, I’ve had to figure out my own way to have a Jewish household and life, and that has meant that I’ve had to be proactive and creative, thinking more about Judaism than I expected to at this point in my life.

Rachel: There are big and little things I have begun to rethink or appreciate about Judaism. I like how the response to hearing someone is pregnant is, “Be’Sha’ah Tova” or “in good time,” rather than “congratulations.” We talk so much in our book about giving up control while at the same time claiming your power (not to mention avoiding early induction!). “In good time” seems much realer and more thoughtful than “congratulations.” After all, not everyone is happy to be pregnant. More significantly, perhaps, I’ve become more and more appreciative of the importance of ritual. At times of transformation we have a great need for ritual. I’m still uncomfortable with many of the orthodox rituals like the mikveh or keeping kosher or covering your hair and yet I find some things—Friday night dinner, rules for mourning, a clear sense of how to provide for and support a new mother—more and more appealing, especially as compared to some of our secular American rituals and rites of passage like hospital gowns, leaving new mothers alone without support, or the customary separation of babies from parents in the hospital. Those seem like terrible rituals.

Specifically, though, you asked about Leah. Being named Rachel I had thought a lot about Rachel from the bible. It’s a very intense story—Jacob’s love for Rachel—and a rather sad story for Leah. After I had children I began to think about these women who had so many children and what that might have been like. I began to understand the burdens and pleasures in a new way. It says in the bible that Leah was given so many children as a comfort for the fact that she was so unloved by Jacob, the names of her first three sons are all about her unhappiness, her affliction of being unloved. Judah is Leah’s fourth son. I had a miscarriage between my second son and my third son. My older sons really chose the name “Judah” for their brother but once I thought about the name I came to love it on so many levels including the way in which it marked a space for the failed pregnancy that is almost entirely invisible and the way in which it made me investigate the parts of myself that are much more like Leah than like Rachel. I could go on and on about this but will leave it there.

Wendy: As a breastfeeding counselor who speaks to postpartum mothers on a daily basis, I was particularly struck by your description of the relationship between birth and the postpartum period:

The culture of fear that surrounds pregnancy and birth has led to a crisis in parenting. So many women believe that their babies almost died. So many women view their infants as fragile, view their bodies as inadequate.

Could you elaborate on the connection between birth and women’s experiences of the “after-birth” period?

Arielle: If a woman is given no agency during her pregnancy or birth process— if her weight and nutrition are taken and recorded without informing her about those things; if she is told her body is too small or her baby too big or her cervix too weak to deliver vaginally; if she is told what to eat, what position to lie in, when to push; if her baby is whisked away from her and given to “experts” immediately after birth so they can “take care of” the baby—well, I think it’s common sense to me to see that this woman’s power and intuition are at enormous risk, and that she might well feel ill-prepared or capable of taking care of her own baby. It seems to me that it’s no coincidence that the increase of intervention at birth has coincided with an increase in the parenting advice industry: there are now hundreds of experts to tell you how to put your baby to sleep, how to wrap it in a blanket, what to buy for it, how to discipline it. In losing our connection to our own abilities to birth, we are losing our connection to our own ability to parent our newborns.

Wendy: One of the most amazing thing about this book is its inventive form. The book begins as a clear enough conversation between the two of you, but often the lines become blurred, and your voices mingle. You also include the voices of other women: women recalling their births, experts in the field, and references to historical birthing pioneers. The book feels like homebirth itself – women helping women, women “holding the space,” as you say, their voices blending and overlapping.

Rachel: Our book is about our friendship as much as it is about birth and feminism. We wanted to work in form that somehow mimicked the very fluid relationship of our friendship—the echoing, constantly interrupted, high satisfying and sometimes difficult conversations about art, family, birth, politics, food, paint colors: about everything.

We’d worked together as editors before but this was our first direct, creative collaboration. Arielle suggested we write about homebirth because she was pregnant and I had just given birth (my first homebirth) and Arielle had recently asked her students to write about a subculture. We began to write back and forth over email and the form grew organically in all directions. We were not interested in writing a kind of thesis/evidence book and wanted the form to feel authentic to our relationship and the way most women we know gather and share information. It’s a kind of storytelling.

Wendy: Many women today are unhappy with the way birth is handled in medical environments, but are scared of birthing outside of it. What would you say to a mother in this situation?

Arielle: First I’d say: educate yourself. Arm yourself with knowledge. Empower yourself. It’s tragic that the majority of parents are making fear-driven choices (and ill-informed ones) around birth. It’s like that slogan about democracy: vote your hopes, not your fears. I’d say plan the birth of your hopes, not your fears. Many studies have shown that out-of-hospital births, attended by skilled practitioners, are as safe if not safer than hospital births, and we quote some of those studies in our book. Our book lists a ton of resources in the back, and there are now so many great ways to find out more about birthing options: from films like The Business of Being Born to books like Jennifer Block’s Pushed to the thousands of amateur homebirth videos and blogs online. I most often recommend Business of Being Born and Pushed, though—and I just realized that both are also made by Jewish women!