Author Archives: Hanna R. Neier

January 17, 2018 by Hanna R. Neier

Top Chef Judge Talks About #MeToo and Latke Reubens with Lilith

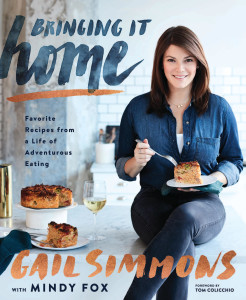

With a prominent role on Top Chef, a new cookbook on the shelves, and a four-year-old daughter at home, Gail Simmons’ plate is full. Working her way from magazine intern to popular TV personality, Simmons has travelled the world, cooked in some of the finest NYC restaurants and launched her own female-focused production company, Bumble Pie Productions. Her cookbook, Bringing it Home: Favorite Recipes from a Life of Adventurous Eating (Grand Central Publishing, 2017), is a collection of recipes inspired by her experiences mixed in with twists on Jewish classics from her childhood.

With a prominent role on Top Chef, a new cookbook on the shelves, and a four-year-old daughter at home, Gail Simmons’ plate is full. Working her way from magazine intern to popular TV personality, Simmons has travelled the world, cooked in some of the finest NYC restaurants and launched her own female-focused production company, Bumble Pie Productions. Her cookbook, Bringing it Home: Favorite Recipes from a Life of Adventurous Eating (Grand Central Publishing, 2017), is a collection of recipes inspired by her experiences mixed in with twists on Jewish classics from her childhood.

Recently, Simmons spoke with Lilith about Latke Reubens, raising an adventurous eater and how the #MeToo movement is affecting a male dominated food industry.

In Bringing it Home , you mention that some of the best Top Chef moments come from contestants tapping into their roots. Can you talk about how your Jewish heritage influenced your love of food and cooking?

GS: Food is such a huge part of all cultures, I think. So much of my Jewish background is from a childhood celebrating holidays around the table. I spent a lot of time learning to make (and eating!) those great dishes that were passed from my grandmother to my mother and my mother to me; things like matzo ball soup and brisket and latkes and my mom’s chopped liver, traditional Eastern European food. When my grandmother and great-grandmother were making these dishes fifty or one hundred years ago, they didn’t necessarily have access to good quality food. The brisket was used because it was a cheap cut of meat—that was the way to cook back in the shtetel. But now I can get really incredible cuts of meat, access really great technique, and make sure the version I make is the best possible one. I try to preserve the integrity of the food, but I take liberties. For example, taking the classic latke, making it the exact same way that my mom made it for me growing up, but making it into a Latke Reuben, adding a great sour cream sauce, a fresh apple slaw and some slices of pastrami because I think it’s really fun.

- No Comments

October 7, 2016 by Hanna R. Neier

How Does Treyf Taste? An Interview with Elissa Altman

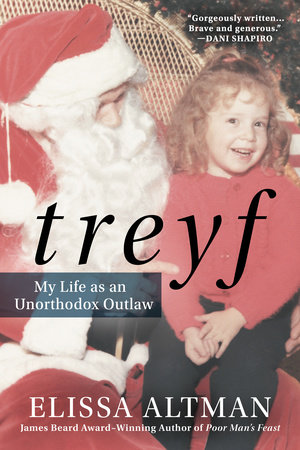

“Treyf… imperfect, intolerable… forbidden… A person can eat treyf; a person can be treyf.” The second memoir by award-winning author Elissa Altman (of Poor Man’s Feast fame), Treyf: My Life as an Unorthodox Outlaw (NAL/Penguin,) is a story of the struggle to find happiness, meaning and a sense of belonging in a world where traditions can both define and isolate us. In her latest work, Altman recalls in vivid detail her tumultuous coming of age and the ways in which food can express the most profound love while also being the catalyst for furious rebellion. From fried Spam [the “luncheon meat”] to her grandmother’s goulash, food marks the key moments of the author’s life in frank yet eloquent narrative.

“Treyf… imperfect, intolerable… forbidden… A person can eat treyf; a person can be treyf.” The second memoir by award-winning author Elissa Altman (of Poor Man’s Feast fame), Treyf: My Life as an Unorthodox Outlaw (NAL/Penguin,) is a story of the struggle to find happiness, meaning and a sense of belonging in a world where traditions can both define and isolate us. In her latest work, Altman recalls in vivid detail her tumultuous coming of age and the ways in which food can express the most profound love while also being the catalyst for furious rebellion. From fried Spam [the “luncheon meat”] to her grandmother’s goulash, food marks the key moments of the author’s life in frank yet eloquent narrative.

Here, Altman discusses with Hanna R. Neier the dual power of food and the need to connect to one’s past while still belonging to the present.

- No Comments

April 5, 2016 by Hanna R. Neier

Jennifer S. Brown, Author of “Modern Girls,” Talks Mother-Daughter Drama and Choosing Abortion in the 1930s

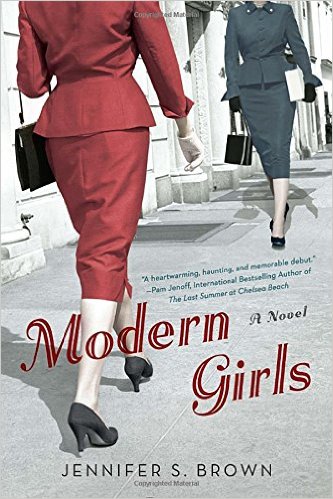

Dottie’s got a great job in Manhattan. She blows her salary on the latest fashions, escapes to the country with her friends when the city is stifling, and is in love with her boyfriend of three years. Her mother’s a stay-at-home, spends her life pushing her kids to make the most of theirs and dreams of her young political days when life used to mean so much more.

Dottie’s got a great job in Manhattan. She blows her salary on the latest fashions, escapes to the country with her friends when the city is stifling, and is in love with her boyfriend of three years. Her mother’s a stay-at-home, spends her life pushing her kids to make the most of theirs and dreams of her young political days when life used to mean so much more.

It’s a timeless story—could be happening right now. Only it’s happening in 1935. And Dottie’s pregnant. And so is her mom. And neither is very happy about it.

Jennifer S. Brown’s debut novel, Modern Girls (NAL/Penguin, April 5, 2016), handles timeless issues of women’s choices, setting it for added drama in the Jewish world of the Lower East Side before World War II. Lilith sat down with the author to talk about mother-daughter drama, having it all, and what makes a Modern Girl.

HRN: This story has some classic relationship drama—mother-daughter dynamics, lovers who can’t commit. Why set it in Lower East Side, New York in 1935? What was the inspiration?

JSB: When I was pregnant with my first child, I went through the genetic testing common for Ashkenazi Jewish women. I asked my father for our family’s medical history, and I was shocked when he told me, “My grandmother had uterine cancer. They thought it was because of that botched abortion, but I’m pretty sure abortions don’t cause cancer.” I started turning the idea over in my mind, playing with it. Why would a married woman during the Depression not want a child? How are her issues different from an unmarried woman? Starting from there, the novel began to take shape.

- 1 Comment

March 21, 2016 by Hanna R. Neier

Fair Labor Lawyer: Bessie Margolin’s Journey from New Orleans Orphanage to Supreme Court Advocate

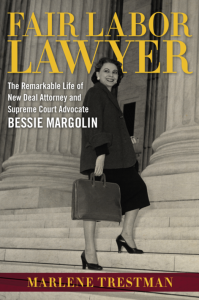

Not every biographer has the keen advantage of having met her subject. Marlene Trestman, author of Fair Labor Lawyer: The Remarkable Life of New Deal Attorney and Supreme Court Advocate Bessie Margolin (LSU Press, March 2016), was lucky enough to not only have known Margolin but also to have been mentored by her.

Not every biographer has the keen advantage of having met her subject. Marlene Trestman, author of Fair Labor Lawyer: The Remarkable Life of New Deal Attorney and Supreme Court Advocate Bessie Margolin (LSU Press, March 2016), was lucky enough to not only have known Margolin but also to have been mentored by her.

From Margolin’s childhood in the New Orleans’ Jewish Orphanage to her Supreme Court advocacy and behind-the-scenes work at the Nuremberg trials, Trestman lets the reader glimpse Margolin’s character, and her sometimes scandalous love affairs which give added dimension to this fascinating historical figure.

Trestman, former Special Assistant to the Maryland Attorney General, is a notable attorney in her own right who was fostered at age 11 by the same Jewish agency that took care of Margolin. Recently, the biographer talked to Hanna R. Neier about Margolin’s struggle with gender inequality, the life of a Jewish orphan in New Orleans, tikkun olam and the Supreme Court.

HRN: Why did you want to write Bessie Margolin’s story?

MT: It’s a bit of a stretch to say I “wanted” to write Bessie Margolin’s story. Instead, as one of the most influential women attorneys of the 20th century, she deserved to have her story written, and I felt I had a duty to find someone who would write it. It took me years before I decided that I could do justice in telling her remarkable story. Margolin and I shared common childhood experiences, albeit separated by 50 years. From 1913 to 1925, she grew up in New Orleans’ Jewish orphanage, which closed in 1946. In the mid-1960s, I became an orphan whose foster care was supervised by the agency that earlier had run the orphanage. We both attended Isidore Newman School, which had been founded to educate Jewish orphans. These shared experiences prompted our meeting, and we stayed in close contact throughout my years in college, law school, and into the start of my career as a government lawyer. She was a generous mentor and powerful role model for me, and we had both received life-changing social services and educational opportunities from two wonderful New Orleans institutions.

- 2 Comments

February 18, 2016 by Hanna R. Neier

“I Wasn’t Stopped by the Glass Ceiling. I Was Stopped by the Parenthood Ceiling.”

Sometimes, you think your life is going to go in a very particular direction. And then, it doesn’t.

Sometimes, you think your life is going to go in a very particular direction. And then, it doesn’t.

Judith S. Kaye, the first woman to serve as New York’s Chief Judge, died this January at the age of 77. Born in 1938 to Polish Jewish immigrants, she paved the way for women in the legal profession. But, ironically enough, she never actually planned on going into law. What she wanted to be was a writer.

Way back when, I too wanted to be a writer. And, like Judge Kaye, I am the daughter of Jewish immigrants who fostered in me the drive to succeed—to get a parnasa, a career, make a living. I spent my childhood writing stories, but shied away from the uncertain livelihood of a freelance writer. I wanted to soar to the top.

So I went to law school. I planned on using my writing skills to advocate for others and support myself, a real parnasa. I graduated law school and got a job doing just that.

I lasted six years.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...