by Hanna R. Neier

How Does Treyf Taste? An Interview with Elissa Altman

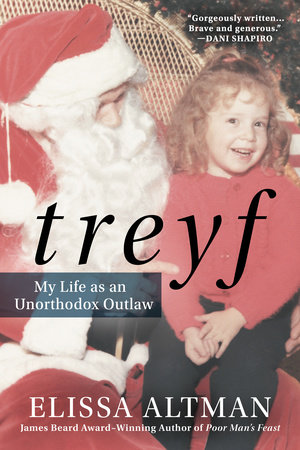

“Treyf… imperfect, intolerable… forbidden… A person can eat treyf; a person can be treyf.” The second memoir by award-winning author Elissa Altman (of Poor Man’s Feast fame), Treyf: My Life as an Unorthodox Outlaw (NAL/Penguin,) is a story of the struggle to find happiness, meaning and a sense of belonging in a world where traditions can both define and isolate us. In her latest work, Altman recalls in vivid detail her tumultuous coming of age and the ways in which food can express the most profound love while also being the catalyst for furious rebellion. From fried Spam [the “luncheon meat”] to her grandmother’s goulash, food marks the key moments of the author’s life in frank yet eloquent narrative.

“Treyf… imperfect, intolerable… forbidden… A person can eat treyf; a person can be treyf.” The second memoir by award-winning author Elissa Altman (of Poor Man’s Feast fame), Treyf: My Life as an Unorthodox Outlaw (NAL/Penguin,) is a story of the struggle to find happiness, meaning and a sense of belonging in a world where traditions can both define and isolate us. In her latest work, Altman recalls in vivid detail her tumultuous coming of age and the ways in which food can express the most profound love while also being the catalyst for furious rebellion. From fried Spam [the “luncheon meat”] to her grandmother’s goulash, food marks the key moments of the author’s life in frank yet eloquent narrative.

Here, Altman discusses with Hanna R. Neier the dual power of food and the need to connect to one’s past while still belonging to the present.

HRN: The desire to belong is a central theme in your memoir. Is treyf your path of transcendence?

EA: I can’t say that treyf itself—that which is forbidden either figuratively or Halachically—is my path of transcendence. I would very definitely say that the desire to belong is human and therefore universal. In Treyf, every person in the story finds themselves faced with the facts of paradox and contradiction; acceptance by one culture often results in rejection by another. Writing Treyf necessitated my examination of the role of cultural acceptance in my life and the lives of the people around me. I grew up in a home that was hobbled by the vagaries of assimilation and the guilt that often runs parallel to it. The relentless questioning of what it meant to be a Jewish American growing up just forty years after the systematic slaughter of millions (including my great grandmother, a poor beet farmer in the Ukraine) was like air and water in my young life. There was a profound amount of survivor’s guilt in my home—no one talked about it but it was omnipresent, almost like a birthright—and it manifested itself in our inability to fulfill our own individual spiritual needs and desires if they diverged from what we were trained to believe. My father didn’t practice his religion at all until he was much older and discovered that he could have his own relationship with it. My mother never practiced her religion either, and still doesn’t show any signs of needing or wanting to. I, on the other hand, have had a lifelong desire for spiritual connection. It’s just always been there for me, like the color of my eyes. At this point in my life, I finally understand where it is fulfilled: my path to transcendence has been found in the everyday kindnesses and compassions that we humans offer to each other, in the face of a very difficult, often brutally violent world.

HRN: Treyf, you write, tasted first of “spite, fury and betrayal.” Can you talk about that?

EA: In my young life, my father’s profound connection to treyf—to the literal, Halachic meaning of the word—always felt to me like a reaction and a response to his own father’s brutality, which was couched in the religious. My grandfather—an Orthodox cantor, and a kind and gentle man to the women in his life (myself included)—believed, as many old-school/fire-and-brimstone folks did and do, that religion was something to be beaten into a wayward child. My father was an incredibly intelligent man and apparently a highly curious little boy: he asked a lot of questions that my grandfather felt shouldn’t have been asked, and he paid the physical price for it. His response, once he was in the Navy away from home and free of the brutal clutches of his father, was to rebel. The surest, most profound way was to gorge himself with treyf. He became incredibly ill from it—from the eating of it and from the guilt that he succumbed to afterwards. I learned from him that food could be bitter, filled with fury, anger, and rage.

HRN: In contrast, you learned from your grandmother that “the food is the love.” Can you explain?

EA: My mother’s mother, Gaga, was the first person who cooked for me specifically. She cooked for all of us, to be clear, but she was the first person in my life who wanted to know, specifically, what I loved and what I didn’t, and she cooked for me accordingly. When she was in the kitchen—when it was just the two of us in the house—I felt connected to her by a cord of profound love, and what she produced was unmitigated sustenance and nurturing in its purest sense. It filled my belly, certainly, but it filled my heart and soul more.

HRN: Throughout your journey, you write that you crave the peace and happiness of your grandmother’s kitchen, and you seek to recreate it. Can you discuss how she influenced you?

EA: Gaga was a circumspect woman with a hot temper: she could go from 0 to 60 in three seconds. She lived her life with an enormous amount of regret and sadness. She was forced into marriage at 33 by the wagging tongues of her Brooklyn neighbors, but the greatest love of her life was her “lady friend” in Greenwich Village, whom she visited several times a week for most of her life. No one talked about it, but we all knew; my grandmother lived her life on the outside of convention, separate from it. Her peace was found in the kitchen, in the art and practice of cooking; it’s where time slowed. It was her safe place. And because she and I were so close (after my mother went back to work in the mid-1970s, it was often just the two of us in my apartment) it became my safe place, too. And it still is.

HRN: At the end of the book, you define yourself as a “modern American.” What does that mean to you?

EA: I defined myself as a “modern American” vis-a-vis the past. I asked: “Isn’t this what my family wanted me to be?” And on one hand, the answer to that question is yes. They wanted me to be safe, to live however I wanted to live, to have the kind of wealth that my forebears only dreamt of. But there is a flipside to that defining of myself. I grew up with piles of pictures of the people who went before me—many of them were born here, many lived in European cities like Vienna and Budapest, and many, like my great grandmother, were poor country farmers who were annihilated simply for being what they were: Jewish. The danger in being a so-called Modern American—whoever we are and whatever we look like—is that it’s all too easy to suffer from a profound disconnect. We live nice, tidy, neat little lives of acquisition, relative wealth and safety. That is the modern American dream. But forgetting where we came from is a luxury that we as humans can ill afford, whether we’re Jewish, Irish, Italian, Lebanese. As we move forward in our lives, we must remain connected to our pasts, to those who came before us. They are the angels on our shoulders.

Hanna R. Neier is a New York City-based writer whose work has appeared in numerous print and online publications including the Jerusalem Post and the Forward. After practicing law for six years as a litigation attorney, she is now a freelance writer focusing mainly on family and women’s issues.