by Merle Hoffman

Abortion Foremother

I came of age in New York City in the 1960s, and I became a child of one of the greatest social revolutions in history, at a time when it became politically possible for women to legally gain and exercise reproductive choice — the power of life and death.

My career started inadvertently while I was still at college, working part-time for a family physician. At the end of each day, I would go into Dr. Gold’s office and he’d talk: about his impoverished Jewish upbringing on the Lower East Side, the anti-Semitism he experienced, and his medical residency at Bellevue Hospital.

He graphically described to me victims of self-abortion: they were so common, he said, that the night shift came to be called the “midnight express.” Women would start the process by inserting foreign devices into their cervixes at home; when they started to bleed, they came to the emergency room, where physicians would perform a procedure called dilation and curettage, scraping tissue from the uterus — essentially an abortion.

At about the same time, I got one of my first whiffs of feminist activism at Queens College, when Florynce Kennedy came to speak. “If men could get pregnant, abortion would be a sacrament,” she said. It was thrilling to hear that kind of unbound language from a podium.

In July 1970, New York State legalized abortion, and Dr. Gold opened Flushing Women’s Medical Center [later called Choices], one of the first legal abortion clinics in the country. He asked me to join him in running it. I was 25; I didn’t have to think twice.

In the two and a half years between New York’s legalization of abortion and January 1973, when the Supreme Court’s Roe decision legalized the procedure everywhere, 350,000 women came to New York for abortions, including 19,000 Floridians; 30,000 each from Michigan, Ohio and Illinois; and thousands more from Canada. By the end of 1971, 61% of the abortions performed in New York were on out-of-state residents. New York City became the abortion capital of the nation.

Legal abortion split the world open to the realities of women’s lives, laid bare in my counseling rooms. They had made the choice to abort, but they still couldn’t believe it was safe and legal.

“I won’t be butchered?” they asked. “I won’t die?” They were sure they’d be punished. “Can I really do this thing and go on with my life?”

Their general ignorance regarding women’s bodies, health and sexuality was also astounding. “Can I get pregnant again after this abortion?” “Will I still have sexual feelings?” Our Bodies, Ourselves had not yet been published; many patients had never had a gynecological exam.

Women described their medical care to me: doctors who told them it was unnecessary to refit their diaphragms after their last childbirth; doctors who refused to insert the I.U.D. when patients asked for them. Women came with pills that were too strong or too weak.

The women came with shame, anxiety, and tangles of questions. “I didn’t have an orgasm, how can I be pregnant?”

The trail of pregnancies caused by doctors’ misinformation or carelessness was endless. I began to call this phenomenon iatrogenic pregnancy.

Most women were examined by a man before they had intercourse with a man. Being a woman meant you were immediately pathologized. Menstruation, sex, pregnancy, abortion — everything had to be explained by doctors.

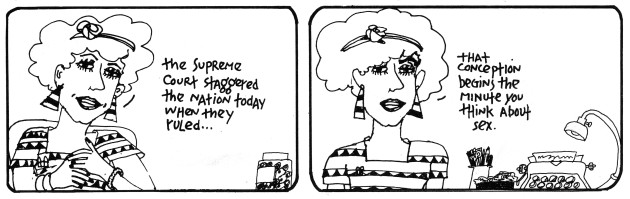

Nicole Hollander

—-

Abortion clinics were poised to be platforms for change, for a woman-centered approach to medical care. Acknowledging patients as a class with rights was a vehicle for combating the victimization of female patients by a generally male

medical establishment.

The most radical aspect of abortion — then legal in just a few states — was the potential for women to turn this situation on its head.

Because this was the first time many of our patients had been in a medical space with someone totally focused on them, they spilled out so much of themselves: their relationships with their parents, distress over boyfriends, fears about their future. We helped them articulate to a stranger something they had never verbalized: why they did not want to be pregnant. To us, they admitted that they did not want to be mothers; they wanted, needed, to have an abortion.

Frustrated by the role of physicians as surrogate fathers and deities, I wrote a Patients’ Bill of Rights and put it on graphic posters showing God (à la the Sistine Chapel) shooting thunderbolts from the sky at patients who responded by holding up placards: “A patient has the right to question her doctor.” “A patient has the right not to be intimidated by the props of medical power — fancy offices, big desks, white coats.” “A patient has the right to ask what tests are being performed. Why? What do they cost?” I called my philosophy Patient Power.

Needless to say, it created a scandal. Doctors tore them off the walls.

—–

I saw so much vulnerability: legs spread wide apart; the physician crouched between white, black, thin, heavy, but always trembling, thighs: the tube sucking the fetal life from their bodies, the last thrust and pull of the catheter, then the gurgle that signaled the end of the abortion. Over and over I witnessed women’s relief that their lives had been given back to them. It was a kind of born-again experience.

But I also spent hours counseling husbands, lovers, sisters, and mothers full of fury. “Let her really feel the pain so she knows never to do this again.” But for the boy or man, there was no censure, never was.

I learned that the reality of abortion resides in “if only.” “I would keep this pregnancy if only — If only I wasn’t 14, I was married, my husband had a job, I didn’t give birth to a baby six months ago, I didn’t just get accepted to college, my boyfriend wasn’t on drugs, I wasn’t on drugs. If only….”

But women found a kind of redemption at the clinic: counselors and staff who did not devalue, but supported, them, who demystified, neutralized, accepted. And, of course, redemption in the form of rescue from an unwanted pregnancy.

Our Reproductive Selves

The articles in this special section:Abortion Foremother

by Merle Hoffman

Ambivalence: When the Abortion on the Table Is Your Own

by Deborah Eisenbach-Budner with Rabbi Susan Schnur

A Ritual for Abortion

by Deborah Eisenbach-Budner with Rabbi Susan Schnur

Don’t Say “VAGINA”

By Sarah Erdreich

The 10 Most Ridiculous New Anti-Abortion Laws (the 11th probably coming to your neighborhood soon)

Generation Midwife

Jessica Angelson talks to Susan Schnur

Please wait...

Please wait...