by admin

Abortion Foremother

I came of age in New York City in the 1960s, and I became a child of one of the greatest social revolutions in history, at a time when it became politically possible for women to legally gain and exercise reproductive choice — the power of life and death.

My career started inadvertently while I was still at college, working part-time for a family physician. At the end of each day, I would go into Dr. Gold’s office and he’d talk: about his impoverished Jewish upbringing on the Lower East Side, the anti-Semitism he experienced, and his medical residency at Bellevue Hospital.

He graphically described to me victims of self-abortion: they were so common, he said, that the night shift came to be called the “midnight express.” Women would start the process by inserting foreign devices into their cervixes at home; when they started to bleed, they came to the emergency room, where physicians would perform a procedure called dilation and curettage, scraping tissue from the uterus — essentially an abortion.

At about the same time, I got one of my first whiffs of feminist activism at Queens College, when Florynce Kennedy came to speak. “If men could get pregnant, abortion would be a sacrament,” she said. It was thrilling to hear that kind of unbound language from a podium.

In July 1970, New York State legalized abortion, and Dr. Gold opened Flushing Women’s Medical Center [later called Choices], one of the first legal abortion clinics in the country. He asked me to join him in running it. I was 25; I didn’t have to think twice.

In the two and a half years between New York’s legalization of abortion and January 1973, when the Supreme Court’s Roe decision legalized the procedure everywhere, 350,000 women came to New York for abortions, including 19,000 Floridians; 30,000 each from Michigan, Ohio and Illinois; and thousands more from Canada. By the end of 1971, 61% of the abortions performed in New York were on out-of-state residents. New York City became the abortion capital of the nation.

Legal abortion split the world open to the realities of women’s lives, laid bare in my counseling rooms. They had made the choice to abort, but they still couldn’t believe it was safe and legal.

“I won’t be butchered?” they asked. “I won’t die?” They were sure they’d be punished. “Can I really do this thing and go on with my life?”

Their general ignorance regarding women’s bodies, health and sexuality was also astounding. “Can I get pregnant again after this abortion?” “Will I still have sexual feelings?” Our Bodies, Ourselves had not yet been published; many patients had never had a gynecological exam.

Women described their medical care to me: doctors who told them it was unnecessary to refit their diaphragms after their last childbirth; doctors who refused to insert the I.U.D. when patients asked for them. Women came with pills that were too strong or too weak.

The women came with shame, anxiety, and tangles of questions. “I didn’t have an orgasm, how can I be pregnant?”

The trail of pregnancies caused by doctors’ misinformation or carelessness was endless. I began to call this phenomenon iatrogenic pregnancy.

Most women were examined by a man before they had intercourse with a man. Being a woman meant you were immediately pathologized. Menstruation, sex, pregnancy, abortion — everything had to be explained by doctors.

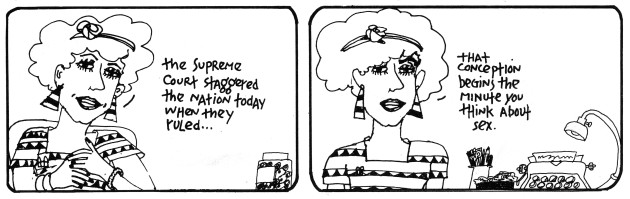

Nicole Hollander

—-

Abortion clinics were poised to be platforms for change, for a woman-centered approach to medical care. Acknowledging patients as a class with rights was a vehicle for combating the victimization of female patients by a generally male

medical establishment.

The most radical aspect of abortion — then legal in just a few states — was the potential for women to turn this situation on its head.

Because this was the first time many of our patients had been in a medical space with someone totally focused on them, they spilled out so much of themselves: their relationships with their parents, distress over boyfriends, fears about their future. We helped them articulate to a stranger something they had never verbalized: why they did not want to be pregnant. To us, they admitted that they did not want to be mothers; they wanted, needed, to have an abortion.

Frustrated by the role of physicians as surrogate fathers and deities, I wrote a Patients’ Bill of Rights and put it on graphic posters showing God (à la the Sistine Chapel) shooting thunderbolts from the sky at patients who responded by holding up placards: “A patient has the right to question her doctor.” “A patient has the right not to be intimidated by the props of medical power — fancy offices, big desks, white coats.” “A patient has the right to ask what tests are being performed. Why? What do they cost?” I called my philosophy Patient Power.

Needless to say, it created a scandal. Doctors tore them off the walls.

—–

I saw so much vulnerability: legs spread wide apart; the physician crouched between white, black, thin, heavy, but always trembling, thighs: the tube sucking the fetal life from their bodies, the last thrust and pull of the catheter, then the gurgle that signaled the end of the abortion. Over and over I witnessed women’s relief that their lives had been given back to them. It was a kind of born-again experience.

But I also spent hours counseling husbands, lovers, sisters, and mothers full of fury. “Let her really feel the pain so she knows never to do this again.” But for the boy or man, there was no censure, never was.

I learned that the reality of abortion resides in “if only.” “I would keep this pregnancy if only — If only I wasn’t 14, I was married, my husband had a job, I didn’t give birth to a baby six months ago, I didn’t just get accepted to college, my boyfriend wasn’t on drugs, I wasn’t on drugs. If only….”

But women found a kind of redemption at the clinic: counselors and staff who did not devalue, but supported, them, who demystified, neutralized, accepted. And, of course, redemption in the form of rescue from an unwanted pregnancy.

As time passed, I could see that the movement for women’s rights had enjoyed a brief period of public popularity in the early seventies that led to the legalization of abortion, but before women really had the chance to move into their power, the public discussion began to move toward the construction of simplistic, judgmental narratives designed to put women back in their place.

Two sides emerged, as if they were mutually exclusive: the “right to life” or the “right to choose.” Each woman’s acceptance of her right was threatened by a Greek chorus screaming “murderer” at her for exercising her power. Most women couldn’t help but internalize these narrow ways of seeing the issue.

Ironically, the New Right and Moral Majority were also in touch with the fact that abortion empowers women. They understood that to keep women in the traditional roles of wife and mother — and thus prevent wholesale societal upheaval — they had to remove a woman’s power to choose.

A study was conducted that revealed a powerful contradiction: the majority of women who came to Choices for abortions did not consider themselves to be pro-choice. They had never imagined themselves in a position where they would decide to have an abortion, an act they considered morally reprehensible even as they waited their turns to be called into the operating rooms. I often asked women who had had abortions if they’d sign petitions, come to rallies, or participate in meetings. Most shook their heads. After their abortions, they just wanted to leave it all behind.

Yet, despite this, they referred their friends and family and came back to the clinic when they needed counseling or care. They demonstrated a quiet solidarity through the necessity of making reproductive decisions. Abortion created “reluctant epiphanies” — the realization that it was not politics but necessity that drives women’s choices.

—-

When I found out that I was unintentionally pregnant myself, I wrote in my diary, “For one night I am a mother.” The next morning I dressed carefully in a red-and-white suit. What does one wear to an abortion? There are no traditional costumes like those for funerals or weddings. There is no ritual from one generation of women to another. There are only functional considerations; you wear something that comes on and off quickly and easily.

The steps of the familiar process played out in surreal reversal. Now I was joined to the common experience of my sex. But as I lay on the table I had stood beside to support so many others, I felt irrevocably alone. Strange how I thought of the fetus as female, as if that shared gender gave me a connection.

—-

By the mid-eighties, abortion defenders found themselves firmly in the midst of a backlash. “Pro-choice” came to mean pro-murder. There was a growing tendency to liken abortion to the Holocaust, to compare the private moral decisions of individual women to the wholesale slaughter of Jews. An abortion clinic in Westchester was labeled “Auschwitz on the Hudson,” and anti-abortion protesters raised placards with Nazi insignias in front of clinics. This analogy between Jews and fetuses was an effective way to humanize fetuses, casting them as victims deserving of civil rights.

But for whom, exactly, were they fighting? Few but the most religiously fanatical would wage a hot war in the name of a group of cells. This war was being fought against women, not for fetuses.

In 1985 alone, there were approximately 150 attacks against abortion clinics. One of our clinic counselors returned home one evening to find her cat decapitated. Patients were called in the middle of the night with recordings of a childish voice crying, “Mommy, Mommy, why did you kill me?”

In June 1990, Brooklyn’s Bishop Thomas Daily recited the Hail Mary more than 150 times in front of Choices, with 1000 demonstrators. But on the day of their protest, none of our scheduled 100 abortions was canceled. In that era, while Daily was gathering his followers to pray the rosary outside my clinic, I was helping run a sort of underground railroad. Women from states with restrictive abortion laws were traveling to New York to have their procedures. I lowered the fees for out-of-state clients and welcomed them with care and compassion.

Choices grew to see over 500 patients for abortions per week. With my staff of 115, I was basically running a midsize hospital. At our height we performed almost 20,000 abortions per year, over 100 per day, making us one of the largest abortion facilities in the U.S. Nearly 97% of the abortions were done in the first trimester at a cost of $300.

—-

I was generous with salaries, including my own. I was the only woman owner of a licensed abortion facility in New York, yet my feminist peers often made me feel as though I was doing something wrong. Many felt that a real activist should

be struggling financially, or at least working for a nonprofit. How, they wondered, could I be a radical feminist and a successful entrepreneur?

Male abortion doctors faced less opprobrium; the fact that they were making money off abortions did not tarnish them the way it tarnished me. I was a woman, a feminist, a writer, a publisher and an activist, and I was making a hell of a lot of money. Something wasn’t right.

—-

An influx of Russian and other émigrés started coming to the clinic in the 1980s. Abortion was the major form of birth control in the Soviet Union, and many of the women had had 10 or 20 before coming to Choices. At one point, a 35-year-old Russian woman came to Choices for her 36th abortion. Most Russian gynecologists promoted the idea that the pill caused cancer and they preached the virtues of repeat abortions.

The lack of choice in Russia resulted in an alarming number of abortions performed both legally and illegally. It was impossible to get an accurate number, but it was estimated that between five and 18 million abortions were performed annually there as compared to 1.6 million in the U.S. Acting out my ultimate rescue fantasy, I travelled to Moscow to work on setting up the first feminist medical center — what I called Choices East.

A Hindu Indian woman, 18 weeks pregnant, came into Choices with her husband and two young sons, seeking an abortion. She’d had amniocentesis to insure that there were no fetal abnormalities, and found there was nothing wrong with her fetus. Why, then, was she here? “It’s a girl,” she told me. “I can’t have a girl. Girls are liabilities.”

I thought of the fetus within her and the primal birth defect it carried. I felt rage that it was my gender that was the least wanted, and despair over the reality that within this act was a denigration, denial, and devaluation of the female self.

The history of abortion is the history of power relations between states and their female populations. When Stalin made abortion illegal, the agenda was to populate Russia with soldiers to counteract Hitler’s rising militarism. Meanwhile, Aryan women in Nazi Germany who were thought to have aborted their fetuses could be punished with the death penalty while those deemed “hereditarily ill” were permitted to have abortions.

Romania offered abortion on request until the decline in fertility instigated a change in policy in 1966; abortion laws enforced by military dictatorships in Chile mandate that women can be jailed for up to five years if they are caught. In China, abortion is an important tool for limiting population growth. In the U.S., the legality of abortion is a wedge issue that flip-flops according to the party in power.

The battlefields are different, but the war is always the same. For women in sexist, authoritarian societies, however, there is often only the harsh reality that sex rarely comes without anxiety, and that the price one often pays for it is high and dangerous.

—-

When Mother Teresa, speaking about abortion, said, “We have created a mentality of violence — massive, propagandized movements that have brought about more than a million and a half unborn deaths every year,” Elie Wiesel didn’t agree with her. He said that the violence he was concerned about was the violence of the abortion debate itself.

I interviewed Wiesel for my magazine On the Issues and said to him, “I personally have been compared to Hitler and been called a great murderer.”

He answered, “It is blasphemy to reduce the Holocaust, a tragedy of monumental proportions, to abortion, which is a human tragedy. We need to give the human proportion back to the abortion issue, and when we do, we may be able to have much more understanding for the woman who chooses it.”

—-

Dr. David Gunn became the first abortion provider killed in the war against abortion, in 1993. After that, there was a sequence of murders, including that of my friend Dr. George Tiller; for many years I referred women to his clinic for therapeutic late-term abortions. Since 1977, almost 200 abortion clinics have been bombed.

Choices had been harassed with many bomb threats, and I received death threats on a regular basis. I hired guards and upgraded my alarm and security systems. We had regular clinic escorts who would courageously come out every Saturday wearing orange Choices vests, but nothing could change the fact that it would take only one act of violence to destroy our fragile sense of security.

Patients would come in crying after hearing the exhortations from anti-abortion “sidewalk counselors” in front of Choices, and, indeed, a great part of many patients’ counseling sessions was spent dealing with these psychological assaults.

At an abortion providers conference in Washington, D.C., I remember finally being handed a button that read, “I’m Pro-Choice and I shoot back.” Some years earlier, buttons read, “I’m Pro-Choice and I vote.”

When doctors first began to perform abortions they were viewed as progressives, or mavericks. Now they were living in a constant state of P.T.S.D. In order to minimize my vulnerability, I purchased a 20-gauge, pump-action Mossberg shotgun.

A journalist from the Daily News got wind of my purchase and wrote, under the headline Make Her Day, “If you’ve noticed the Right-to-Life crowds thinning in front of Choices Women’s Medical Center in Queens, maybe it’s because the abortion clinic’s president, Merle Hoffman, just purchased a shotgun.”

—-

There was also an avalanche of economic and political attacks. Choices’ new landlord made it clear that he had no intention of having an “abortion center” continue to be a tenant in his building. He threatened to “bulldoze” my space if I remained one extra day after the expiration of my lease.

With so little warning, I was forced to liquidate my entire savings to cover the costs of speeding up construction on our new site. We moved, but the building was sold to a new owner who was anti-abortion — and committed to making my life miserable. His harassment was so severe that I had to call Attorney General Janet Reno’s office, which provided armed federal marshals to guard my space during the last few months of construction.

Over the course of two years, the landlord left Choices without heat and air-conditioning, and unfinished roof work resulted in multiple floods. I had to delay paychecks, lay off staff and suspend all advertising, resulting in a drastic reduction in my patient population. In order to meet payroll and get supplies, I had to stop paying taxes.

I was going from one lawyer to another as I tried to stave off bankruptcy, keep the builders working, the clinic open, the patients safe, and my own sanity intact.

—-

We spoke with every patient individually prior to her abortion, but it became increasingly clear that abortion could not be extricated from other issues women brought to the clinic — violence at home, abusive relationships, incest, danger on the streets, harassment in the workplace, and economic assaults.

In response to this, we added the Choices Mental Health Center to our clinic. I’d once helped teach women how to scream at the Brooklyn Martial Arts Center. But as Sally Kempton said, “It’s hard to fight an enemy who has outposts in your head.” Part of the work of our Mental Health Center was to help women feel their power and resist the enemy within as well as without.

—-

“Welcome to my world.” My words were published in the New York Post on October 12, 2001, just a little over a month after the 9/11 terrorist attack on the World Trade Center. It was a controversial statement, but it was the truth. I was used to checking my mail for white powder [anthrax] every day. I’d been looking under my car for signs of foul play, my heart beating quickly in anticipation of an explosion, for a decade by then.

I’d been avoiding windows for fear of bullets since Barnett Slepian was gunned down at his kitchen window in front of his wife and children in 1998. I tensed my body every time I walked from my car to Choices.

Saying, “I had an abortion” aloud hasn’t gotten any easier since I opened an abortion clinic in 1971— 42 years ago. It is ever a tragedy, a necessary evil, something to be kept private and about which to feel ashamed.

The future of abortion still comes down to that fundamental question: When will we have abortion without apology?

Adapted by Susan Schnur from Intimate Wars: The Life and Times of the Woman Who Brought Abortion from the Back Alley to the Boardroom (The Feminist Press, 2012)