Tag : tashlich

April 2, 2019 by admin

Fiction: What Forgiveness Might Look Like

Art: Ofri Cnaani

Dana and her husband, Jonathan, stand next to each other on a footbridge, separated by a loaf of stale bread and a gulf of regret. Below them, a few dozen members of their congregation lace the shoreline of Rock Creek. Save for Dana and Jonathan they are either families with children or gray-haired empty nesters.

The first year they were married, Jonathan had pulled her along to the tashlich service, the symbolic casting away of sins at the start of the Jewish new year. The ceremony, in which bits of bread are thrown into a body of water, didn’t move Dana the way it moved Jonathan. As far as she could see, they were both good people without much to apologize for. She wasn’t too stressed about her name being inscribed for another year into the Book of Life, whatever that meant. Jonathan had said it was a nice excuse to take a break from the busyness of life, to experience a sense of renewal. Dana had said it was an elaborate way to feed ducks.

But now she is five years into her marriage and wonders if redemption is possible. What forgiveness might look like.

Their synagogue dues have been paid for by Jonathan’s parents, Howard and Barbara. If only Dana and Jonathan lived closer, Barbara had lamented, they could come to Temple Beth El for services. But since the annual fee at B’nai Israel included tickets for the High Holidays, the in-laws reasoned, the membership almost paid for itself. Plus it had a nursery school, Howard had said with a gleaming smile.

What Howard and Barbara never considered was that it wouldn’t have occurred to Dana to worry about attending services on the High Holidays. Her parents had separated during the year leading up to her bat mitzvah, and while they had shielded her from their feuds over child support and visitation times, they did not spare her the spectacle of their arguments over the guest list or the budget for her party. Her father accused her mother of thinking she was planning a wedding, while her mother retorted that she couldn’t do everything on a shoestring, and solved the problem by slashing most of her father’s guest list. To the extent that the day had felt joyful, it was because the whole ordeal was over. After that her parents let their synagogue membership lapse. That it was no longer needed seemed to be the one thing they could agree on. Dana didn’t attend services again until she met Jonathan.

And now here she is on a bridge, cradling day-old bread. Cantor Joan, a slender woman wearing a flowing lavender dress, white prayer shawl, and beaded kippah made of silver wire, smiles as she leads a niggun. The notes of the wordless chant seem to lift her body. She does not look like someone who has come to the water to unburden her soul, Dana thinks. She looks like someone who loves her job. As the song concludes, Cantor Joan opens her prayer book. In the open space of nature, with no walls or ceiling, and with the sound of cars passing on the parkway above the water, she shouts to make herself heard.

“Micah said, ‘God will take us back in love. God will cast— tashlich—our sins into the depths of the sea,’” she calls. “Micah is telling us that we can separate ourselves from our past sins.” She pauses and surveys the crowd. “Just as the water carries away these crumbs, our mistakes can be carried away too.” She closes her prayer book and throws some bread into the water, then turns out her dress pockets to shake them over the water’s edge.

Dana clutches the crusty oblong loaf, which protrudes from the white paper bag. She feels a tug as Jonathan breaks off a piece. He holds it in both hands. He is crying.

“I don’t know where to start,” he says.

“We probably should have brought more bread,” she says.

JUST WEEKS BEFORE, THEY HAD BEEN STANDING in their kitchen prepping dinner when Dana said, “I called the clinic today. There’s been a cancellation. They can see us this Friday.” Dana was chopping vegetables and didn’t look up when she said this.

“Have you been calling them every day?” Jonathan asked, peering from behind the open refrigerator door.

“Well it’s not like we have time to waste.” Dana pushed a pile of carrots to one side with the back of the knife blade and set to work on a red pepper. Jonathan came to one side and picked up a couple of carrot spears.

“I’m sorry, Babe, but I have a meeting Friday.”

Dana wondered why he had to chew so loudly. “You didn’t even ask me what time.”

“Okay, what time?” Jonathan took another bite of carrot.

Dana put the knife on the cutting board and turned to look at her husband. “Unbelievable,” she said.

“Well who knew getting pregnant could be so inconvenient? Can’t we just go the old-fashioned route?” Jonathan shimmied his hips from side to side and licked his remaining carrot stick. Dana was unsure whether he was trying to be sexy or if he was making a joke about how people look when they are trying to be sexy. Either way she was not impressed.

“We’ve been going the old-fashioned route for over a year. We could’ve had a baby by now.”

“My parents said it took them two years to conceive me.” Jonathan slid the carrot into his mouth and reached for a bit of pepper. His temples pulsed as he chewed.

“You’ve talked to your parents about this?”

“My mom says that women who are too health conscious sometimes don’t ovulate.”

“She’s just pissed because I actually have some control over what I put in my mouth. And what comes out of it for that matter. She’s probably blabbed to her whole book club that I can’t get pregnant.”

“Why do you care what some old ladies are talking about at their book club?”

“You’re right. I don’t care about that. I care that you talk more to your parents about our problems than to me. You’re not a child. Your parents don’t need to be involved in every aspect of your life.”

“I just think you should relax.”

“Who gave you that advice—your mom or your dad?”

“How about we open up a bottle of red? I bought a nice Cab on the way home.”

Dana wiped her hands on a dishtowel and shouldered past her husband. “I’m going to work out. The appointment’s at 2:30 on Friday. Make it work.”

At the gym, Dana set the treadmill to a faster setting than usual. The whirring of the machine coupled with the pounding of her feet on the belt didn’t quite soothe her, but it brought some satisfaction. Her phone lay in the cupholder, and she saw it light up. A text from Jonathan.

“Remind me and I’ll c if I can move my meeting”

This, Dana thought, was what passed in Jonathan’s mind as an apology. She tossed the phone back in the cupholder, turned up the incline of the treadmill. Her phone flashed again.

“Have you called insurance to make sure fertility covered”

Dana typed, “maybe you should have your parents call the insurance company,” but didn’t hit send. She tossed her phone back into the cup holder, with the screen turned away from herself.

That’s when she noticed Marco from her spin class. When they met she had enjoyed his flirtatious asides—his funny facial expressions evoking the instructor’s overplucked eyebrows, the way he would wink at her and sing along every time a Madonna song came on. He had suggested they exchange numbers so they could coordinate their workouts. Dana had assumed he was gay.

He wasn’t.

She found out when she complimented his new workout clothes, green-trimmed mesh shorts cut high on the side with a tank top that showed off his arms. Dana had reached out to pinch the piping along the hemline. Marco caught her hand and gave it a squeeze. Dana pulled away and hopped onto her bike. When the class ended he asked if she wanted to grab a bite to eat. She told him she had to get up early for a work meeting.

Now she decided to ask him for a drink. Marco didn’t seem at all surprised by her invitation. He said he knew a place a block away with a great deal on margaritas.

They found two seats at the end of the bar. They laughed easily over small things, inventing nicknames for the other spin class regulars. When Dana realized they had drained the pitcher Marco had ordered, she hopped off her barstool, said she should be getting home. Marco stepped down from his seat too, leaving only inches between them. “Let me guess—early meeting?” he smiled, his eyes on her mouth. His teeth were perfect.

“Well, not too early,” she said, rolling onto the balls of her feet to kiss him.

NOW, DANA STARES DOWN AT THE WATER. “I never meant for it to happen,” she says.

It’s warm for September. A hint of sewage wafts upward, turning Dana’s stomach. She takes a bit of bread and holds it in her mouth. Focuses on the sensation of it moistening and softening upon her tongue. A bicyclist coasts across the bridge; the wooden boards rattle under Dana’s feet.

Cantor Joan and the congregants begin to drift away. A little girl in red leather shoes and oversized hair bow toddles to the water. She leans forward to grab a stick that is peeking above the surface. The front of her dress dips into the creek. Muddy water drips down her shins, soaking her lace-trimmed ankle socks. Her father, unruffled, rolls up the sleeves of his crisp buttondown shirt and scoops her up from behind. Dana expects him to be annoyed, but he bends his neck to kiss the top of his daughter’s head. He is tall and slender like a heron, or a stork. He holds his child like a prize.

Jonathan watches the father pick his way up the embankment, then sends a morsel of bread sailing over the metal railing.

“I’m sorry,” he says.

“Why are you sorry?” Dana asks.

“I’m sorry I dragged my feet on fertility treatment. I’m sorry I questioned the cost.”

Dana swallows. “That doesn’t justify what I did.” She holds some bread over the water and lets it drop.

“True. You’ve ripped my guts out, Dana.”

Dana’s eyes fill with tears. She knows that if she blinks they will stream down her cheeks. But it doesn’t seem fair to cry.

“Who is it,” Jonathan asks, “that guy from the gym? Matteo?”

“Marco.”

“Marco. Jesus. I feel like such an idiot.” Jonathan takes a deep, jagged breath in, lets it seep out through his lips. “Can you at least tell me it’s over?”

Dana tears off another piece of bread and considers how to answer this question. Marco had been better at flirting than he was at fucking. Once inside his apartment that night, his clumsy fingers fumbled across her skin like furry caterpillars. He pushed his tongue so far into her mouth it felt like he was licking her molars. They shared his bed with a pile of unfolded laundry, which smelled like it had been forgotten in the washer for a day or two before being transferred to the dryer. A bit of trash crinkled under her shoulder blade as Marco moved on top of her. By the time he finished and heaved his body down onto the mattress beside Dana, one leg strewn across her pelvis like a fallen tree limb, she was sober enough to notice the row of half empty glasses lining the windowsill above the bed. The old metal blinds were open; the light from the street gave the room an orange glow. She reached under her back and pulled out the foil wrapper of an energy bar. Within moments, Marco was snoring. Dana pushed his leg aside and collected her clothes into a bundle against her chest. Deciding the shower was probably even filthier than the bed, she dressed in the hallway before slipping out for home.

After that, Dana stopped going to spin class. Changed her gym schedule to avoid running into Marco. He texted once, “where u been?” Jonathan read it over her shoulder, asked who Marco was. “Just a friend from the gym,” she said, and deleted his contact information from her phone.

Then her breasts were sore. Her period was late. She peed on a stick.

“It’s over with him,” she says. “It’s been over for weeks.”

IT HAD BEEN DANA WHO CANCELLED the clinic appointment. After her failed experiment with Marco, she needed time to think. She told Jonathan that he was right, that they should be patient. But then she avoided him. Stayed late at work. Went to bed early. After just a couple of weeks, going to bed early became less about staying away from Jonathan and more about giving her body something it craved. Rather than flailing in the darkness, she slumbered. Would wake feeling like she had been flattened by a steam roller, so would hoist the blankets to her chin and descend back into her dreams.

When she was awake it was difficult to mask the changes in her appetite. Vegetables held no appeal now. She kept pretzels and Wheat Thins at arms’ reach. She discovered that avoiding an empty stomach was the best way to keep from throwing up, so she stashed almonds in her nightstand. Carried a little container of grapes in her purse to pull out one by one on the Metro.

She sensed that Jonathan noticed a change in her. Felt his eyes resting on her as she trailed back to their bedroom at 8 o’clock. But he said nothing. She wanted him to confront her. Scream at her. Instead he looked at her with a searching sadness that told her he was worried about her. He would reach out to touch her elbow, her shoulder. She pulled away.

“YOU’RE PREGNANT.” HIGH ABOVE, a breeze rustles the tulip-poplar leaves. Dana drops another bit of bread into the creek, watches it bob in the water before the current pulls it under the bridge and out of sight.

“I don’t know how to wash this away,”she says.

“Would you want to wash it away? Even if you could?”

“I want a baby, but I don’t know if I want this baby. I want your baby.”

“Are you sure about that?”

“Of course I’m sure. I love you, Jonathan.”

FINDING OUT SHE WAS PREGNANT WAS nothing like she had imagined it would be. No rush of joy, no Jonathan scooping her into an embrace as they hugged and laughed in their narrow bathroom. Instead she sat on the toilet, pants around her ankles, watching the absorbent material inside the pregnancy test wick her urine upward, immediately turning both lines blue. She didn’t have to look back at the package instructions to know what it meant. She felt her heart—the organ, not the symbol of love—open and empty as the blood blossomed up through her neck and filled her ears, flooding her mind with fear.

“I KEPT TELLING MYSELF YOU’D GET pregnant when the time was right. But in the back of my mind I was afraid the problem was me. Looks like I was right,” Jonathan says. He puts his elbows on the railing, cradles his forehead in his palms. His shoulders rise and fall with quiet sobs. Clipped to his soft curls is the black suede kippah he wore at their wedding. Their names and anniversary date are embossed in silver on the inside. The same date is engraved inside their wedding rings. Dana tucks the bread under her arm and looks down at her ring, twists it with the fingers from her opposite hand. Whether it’s the heat or the pregnancy, it doesn’t want to turn. She slides the rest of the loaf from the bag and flings it over the railing. It lands with a thud in the shallows.

“I’ve ruined everything,” she says, and turns to go.

“That’s it?” Jonathan looks over his shoulder at her, his voice rising. “You’re giving up just like that?”

“Aren’t you?” she says, turning back around.

“You’re my family, Dana. Baby or no baby.” This word—family— makes Dana realize she hasn’t felt like a part of one for a long time.

“I don’t know how you’ll ever be able to forgive me,” she says. “Or how I’ll ever forgive myself. It would take an ocean to wash this mess away.” She crumples the empty bread bag into a ball.

“I don’t know either,” he says, wiping his nose with the back of his hand. “But I think I want to try. If you do.” He moves toward her and tucks her hair behind her ear. “Do you want to try? To be a family?”

Dana looks at the water. With the exception of the soggy loaf of bread, it is beautiful. She reaches for Jonathan’s hand and allows her own tears to fall. “Yes,” she says. “I do.”

Briana Maley’s fiction has been published in Chaleur Magazine, Literary Mama and The Passed Note. She lives in Takoma Park, Maryland.

- No Comments

July 15, 2014 by admin

A Woman’s Tashlich

It’s been 18 years since Marcia Falk, renowned Jewish feminist scholar and poet, brought us her groundbreaking The Book of Blessings: New Jewish Prayers for Daily Life, the Sabbath, and the New Moon Festival, a prayer book that not only uncoupled liturgy from patriarchal themes and imagery, but that gave women —and continues to give women —contemplative, gender-corrective ways to connect to the sacred.

It’s been 18 years since Marcia Falk, renowned Jewish feminist scholar and poet, brought us her groundbreaking The Book of Blessings: New Jewish Prayers for Daily Life, the Sabbath, and the New Moon Festival, a prayer book that not only uncoupled liturgy from patriarchal themes and imagery, but that gave women —and continues to give women —contemplative, gender-corrective ways to connect to the sacred.

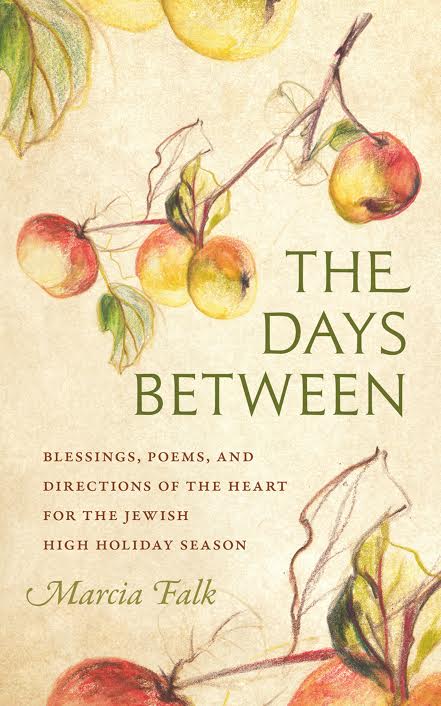

In Falk’s new book, The Days Between: Blessings, Poems, and Directions of the Heart for the Jewish High Holiday Season (Brandeis University Press), she takes us further down the same spiritual path, reminding us that it is good to experience “the turning of the Jewish year” in nature, and that it is holy to immerse ourselves mindfully in endings and beginnings, in solitude and in relationships. “What kind of life will we live in the time we have?,” Falk asks. “Where in our life will we find purpose and meaning?”

Falk underscores that the period between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur (Aseret Y’mey T’shuvah) is intended to be a continuous devotional span; “ten days of meeting oneself face-to-face, opening the heart to change.” The word “between” in the book’s title palpates one of women’s special strengths: connection. Alas, we humans cannot stop time —we can’t make our six-year-old stay six forever, or bring a beloved deceased person back to life —but we can strive to be “fully aware of our connectedness to everything in our world,” and in that way live ourselves into “wholeness, serenity, and fulfillment.”

I asked Marcia if she would take a walk with me, for tashlich, along a river’s edge, using five poems from The Days Between as guideposts. (Tashlich is the ceremony in which Jews throw crumbs into the water to symbolize casting away our sins. In The Days Between Falk calls her new ritual Nashlich, which is gender-inclusive, “we will cast,” rather than Tashlich, “You [God, masculine] will cast.”) In the pages that follow here, she does this, helping me journey spiritually through her translations of poems by the well-known Hebrew poets Zelda and Leah Goldberg, and by the less well-known Yiddish poet Malka Heifetz Tussman. We begin our walk with Falk’s own poem, which revisions Micah 7:19, the biblical verse that opens the traditional tashlich. As we recite and then discuss the poems, they become cast as a prayer cycle. (I have distilled our conversation.)

Each of the poems, says Falk, “uses the archetypal sym- bol of water as revelatory, transformative, and redemptive.” Each “explores time, change, and mortality in the context of intimate relationships; and in each, water is given a voice. Zelda’s sea sings, Goldberg’s river hums, Tussman’s creek babbles.”

Reader: Take a walk with us. Put some crumbs in your pocket for tashlich, and find a serene place alongside water…water that eddies or babbles, water that cascades or crashes, water that hardly ripples. Enter “the between,” give voice to a conversation with your life, move forward along the meridian of deepening t’shuvah.

Hey, you! Come along, too.

CASTING AWAY

We cast into the depths of the sea our sins, and failures, and regrets.

Reflections of our imperfect selves flow away.

What can we bear,

with what can we bear to part?

We upturn the darkness, bring what is buried to light.

What hurts still lodge,

what wounds have yet to heal?

We empty our hands,

release the remnants of shame,

let go fear and despair

that have dug their home in us.

Open hands, opening heart —

The year flows out, the year flows in.

—Marcia Falk

MARCIA FALK: The High Holiday language is full of power and terror, and the verse from Micah that we recite for the traditional tashlich ritual is vivid, almost violent, asking God to hurl all our sins into the depths of the sea. I have a different image of the new year, of life and change. A wave comes to shore and then pulls back, there’s ebb and flow. Is it only our “sins” that we need to let go into the sea?

SUSAN SCHNUR: In the third stanza of Casting Away, you ask, “What can we bear?” Help me understand this.

FALK: For example, can I bear to live with the knowledge that I was mean to my child? Can I accept the “mean” parts of myself? Can I forgive myself?

SCHNUR: And then the poem asks, “With what can we bear to part?”

FALK: Yes. What can we let go of? I’m in the process of clearing out 20 years of clutter from my house, and I’m overwhelmed. I have to look at each thing: Can I part with this? Can I part with that? It can be hard to let go, to stop looking backwards. This is the time of year when we want to be able to walk into the new, but the old holds us hostage. Can we “release the remnants of shame,” let go the despair that has “dug [its] home in us”? The holiday is about perfecting ourselves —but not everything can be changed. Can we accept ourselves?

SCHNUR: Okay, here’s what I want to personally ponder in the palimpsest of this poem: This year, can I live less reactively in life’s ebb and flow?

FACING THE SEA

When I set free

the golden fish,

the sea laughed

and held me close

to his open heart,

to his streaming heart.

Then we sang together,

he and I:

My soul will not die.

Can decay rule a living stream?

So he sang

of his clamoring soul

and I sang

of my soul in pain.

—Zelda

FALK: Now we come to “Facing the Sea,” in which the speaker finds this Other —the sea —that is so unlike her. The speaker is quietly suffering, but the sea is noisy, laughing, bubbling over. Nature is completely alive, always alive —this noisy sea, embrac- ing us, holding us close.

SCHNUR: “My soul will not die”—they sing together about their shared immortality, that dying never conquers life. But the speaker remains so alone. The “Other” can only comfort us up to a point. Is that right?

FALK: The speaker lets something go —“the golden fish,” what- ever that is —and she is embraced. Then the speaker and the sea sing together, but their voices are very different. This poem, for me, is about being in pain and trying to find comfort.

SCHNUR: Here’s what I think I need to think about here: Can I learn to accept someone else’s imperfect love? Can I sing with the universe?

THE BLADE OF GRASS SINGS TO THE RIVER

Even for the little ones like me,

one among the throng,

for the children of poverty

on disappointment’s shore,

the river hums its song,

lovingly hums its song.

The sun’s soft caress

touches it now and then.

My image, too, is reflected

in waters that flow green,

and in the river’s depths

each one of us is deep.

My ever-deepening image

streaming away to the sea

is swallowed up, erased

on the edge of vanishing.

And with the river’s voice,

with the river’s psalm,

the speechless soul

will sing praises of the world.

—Leah Goldberg

FALK: This poem and the next are from a sequence by Leah Goldberg called “Poems of the River.” In the first poem here, a tiny blade of grass sings to the river. We all feel, at some time in our lives, that we’re “on disappointment’s shore,” that we are insig- nificant, “children of poverty”—a very touching phrase for me. But nature can comfort us —“the sun’s soft caress.” The river, in fact, takes our “images” —our faces, our selves —and deepens them.

When our mind quiets down, we get to sing “with the river’s voice, with the river’s psalm,” and we finally feel ourselves part of everything. Water here is wholeness, vitality, moving, streaming away to the sea.

So many of us experience ourselves as small—“even for the little ones like me” is such a poignant image. Why does the little blade of grass want to assure us that the river hums for us, too, lovingly? The blade of grass itself becomes our comforter.

SCHNUR: I love the rushing compassion of this poem. I want to say, “Yes, yes. Don’t leave without me!” This poem makes me want to think about the spiritual challenge of trust. Can I trust that everything will be okay?

THE TREE SINGS TO THE RIVER

He who carried off my golden autumn,

who with the leaf-fall swept my blood away,

he who will see my spring return

to him, at the turning of the year —

my brother the river, forever lost,

new each day, and changed, and the same,

my brother the stream, between his two banks

streaming like me, between autumn and spring.

For I am the bud and I am the fruit,

I am my future and I am my past,

I am the solitary tree trunk,

and you—my time and my song.

—Leah Goldberg

FALK: Ah! Here we find a less quiet voice, the self-possessed voice of the tree describing its relationship to the river. We don’t normally think of “blood” [in the second line] when we think of trees; we associate that with animal life, and when the animal is drained of blood it dies. The image is shocking, even suggestive of domination and submission: the river carries away the tree’s life-blood, yet the tree returns to the river again and again. Or, another way to look at it: perhaps the voice is defiant; it will not die, it will return, year after year.

There’s movement, a shifting of perspective. In the second stanza, the tree and the river are kin: the river streams, like the tree, between seasons. But in the last stanza the tree lets the river know that he, the tree, is solitary, whole in himself: “I am the bud and I am the fruit, I am my future and I am my past.”

Then, at the end, there’s a powerful reversal. The tree no longer addresses the river in the third person—as “he,” as “my brother”—but says, “you—my time and my song.” We aren’t solitary after all. There’s always “the other,” we exist in time, vis-à-vis the other. What is my voice if I’m just talking into the emptiness? I don’t have a voice unless I’m speaking to you.

SCHNUR: This poem breaks my heart. The tree is learning how to move from Martin Buber’s “I-It” relationship —separate, detached, full of defensive bravado—into an “I-Thou” relationship—of mutuality, of reciprocity, of touching interdependence. This challenge hits home for me: Can I learn to be more empathic and more yielding in my relationships?

from TODAY IS FOREVER

I stroll often in a nearby park —

old trees wildly overgrown,

bushes and flowers blooming all four seasons,

a creek babbling childishly over pebbles,

a small bridge with rough-hewn railings–

this is my little park.

It’s mild and gentle

in the breath-song of the park

and good to catch some gossip

from the flutterers and fliers.

Leaning on the railing of the bridge,

seeing myself in clear water,

I ask, Little stream,

will you tumble and flow here forever?

The creek babbles back, laughing,

Today is forever:

Forever is right now.

I smile, a sparkful of believing, a sighful of not-believing:

Today is forever.

Forever is right now…

—Malka Heifetz Tussman

FALK: This last poem is a little touch of mameloshn [Yiddish] in the middle of my book. Once again, water gives us its wisdom. The speaker talks to a stream, sweetly, as though to a child: “Little stream, tell me. Will you be here forever?” Human beings want to know! Are we going to live or die? What’s coming next?

And the creek laughs: Why are you asking such a question? This is what there is! “Today is forever.” The poor creek to have such a foolish disciple!

SCHNUR: Yes, how can we humans think about ourselves with- out thinking about the fact that we will die?

FALK: In every nature poem, there’s a dark thread. I like this poignancy; so much of Jewish liturgy doesn’t acknowledge it. I’m talking about sadness. There’s awe, fear, trembling, God is big, we’re small, all of that. The Kaddish: we exalt You, we enlarge Your name. How does that help one feel better? You’re sorrow- ing, you’re grieving, and what does the liturgy give you back? A big silence. Not much comfort. These poems by Jewish women offer us more.

SCHNUR: This poem asks the biggest question perhaps. Here go my last breadcrumbs into the water. How can we acknowledge life’s sadness? Can we do so and smile?

Sections in blue are excerpted from “The Days Between: Blessing, Poems, and Directions of the Heart for the Jewish High Holiday Season,” © 2014 by Marcia Lee Falk.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...