Tag : Susan Schnur

October 7, 2014 by admin

Say Yes to the Dress

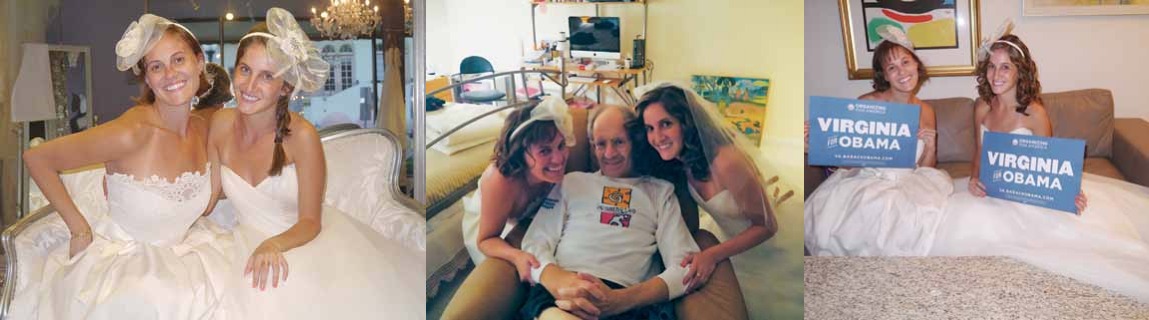

- Shira Sternberg (short dress and short hair), and her sister, Tava Sternberg (long dress and long

hair) and their father, Rolf Sternberg.

On october 5, 2011, I got a text from my father. He was at home in Shaftsbury, Vermont: “Please call me when you can.”

I knew it wasn’t good. He’d had three 911 “episodes” in the previous four months — lightheadedness, fainting, stuff that just felt foreboding — and I’d been, well…kind of waiting.

I was in a work meeting in D.C., and immediately stepped out.

“Hi, Daddy,” I whispered tentatively.

“Shira,” he said, instead of the usual “SHIRA!!!” — letting the whole world know that talking to one of his daughters was the greatest part of his day, week, month, year, life. He was crying and could barely speak. “I had some tests done, they are still waiting for the results, but they think I have c…, ca…, can….. “ He couldn’t say the word.

For him, it was the worst possible diagnosis, since he’d taken care of my mother for 16 years (since I was four, and my sister Tava was an infant), helping her endure treatment after treatment for breast cancer, and he’d developed a scrupulous anticancer “religion” to protect himself from anything that might resemble her fate. He ran a precise distance every day; he never drank, never smoked; he eschewed all red meat and most dairy; and he followed a ritualized daily diet, which everyone who knew him made good-natured fun of: his dinners, for example, were steamed broccoli and mashed potatoes — the latter consisting of a potato mashed with itself.

He and my mother, both lawyers, had become very knowledgeable and active in the cancer prevention world; she helped found the National Breast Cancer Coalition with Fran Visco.

“I’ll be on the first flight home,” I said. My sister Tava, in graduate school for dietetics in Boston, also headed home. At least we’d all be together. By March 2012, I had relocated to Boston, and Tava and I spent every weekend in Vermont. That May I ran my first marathon. On some level, illness, death, and the genetically transmitted BRCA gene had made our family into one organism: we each did what we could to stay healthy.

My father had always taken issue with some mainstream (Western) medical practices, and he decided to participate in a holistic cancer-treatment program in Longboat Key, Florida. I visited him there in April and saw that his health was deteriorating. He didn’t acknowledge that he was dying, but he was. Of esophageal cancer.

In June, he came back to Vermont, saying that he loved New England summers (that’s true) and that he needed to oversee some house renovations — a new bathroom for me, and a roof that was supposed to last 50 (instead of the usual 20) years. In retrospect, it’s clear that Dad was just “prepping” the house for us; he didn’t want to leave his daughters with a place full of problems. In mid-July, he went back to Florida.

It was mid-September — I was at a friend’s wedding in D.C. — when I got a frantic call from Tava. Dad had a doctor’s appointment the next day, and according to a close family friend, “it would be best if [I] were there for it.” I called Dad, but he poo-pooed the urgency. Then he cried. I left the wedding and went straight to the airport.

The next morning I told Tava that now was the time to take the semester off from school; Dad didn’t have much longer. She was with us for a full week in Longboat Key before she mustered up the courage to tell Dad that she’d un-enrolled for the entire semester.

“What?” he said, in disbelief, looking up at us with sweet, childish eyes. “I took the whole semester off, Daddy,” she repeated.

“Well,” he said with resolve, “I better get well really fast.”

Mid-October ushered in one killer day after another. October 13 was the first day that Dad no longer had the strength to leave the house. On October 15, I turned 30 (Mom had died when I was 20). On October 16, I got the results of my own BRCA gene testing. Like Mom, I was positive. (Tava has since tested negative.) The gene is known to increase one’s risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer, though there is no data on how much regular exercise and a healthy lifestyle can shift those numbers. I told Dad the results of my test, and he advised me not to undergo preventive mastectomies. Overall, it felt like there was just too much grief and fear to process, and that our hearts and heads couldn’t work fast enough.

On October 17, my sister and I took our daily, hallowed car trip to Whole Foods. Though Dad wasn’t eating, he had hourly requests for new weird items: bacon, tapioca pudding, Thai soup. The trips were important for us; Dad wouldn’t let us talk about the fact that he was dying in his presence.

“It’s my job to get better” is all that he would say — he couldn’t tolerate knowing that he, like Mom, was doing something that only a bad parent does: die prematurely. He remained firmly in denial. In the car, Tava and I had truthful moments of planning for Dad’s death and memorial service, and our sisterly sharing buoyed up how lonely this all was, making us close.

As usual, we passed La Mariée, the local bridal shop — a place we’d passed dozens of times — but this time, for some reason, I burst into wracking sobs.

“Dad won’t know the man who becomes my husband,” I wailed.

“Get it together,” Tava said. “Shira, you have to get it together.”

“But I was supposed to have a baby before I turned 30; it decreases your risk of getting cancer. I’m 30, Tava, I’m 30!”

“Well, it didn’t happen,” Tava said. “You’ll meet someone, Shira. You’ll have children.”

“I’ll just do it,” I said, sobbing. “I found this person, we’re going to get married. Here’s the plan. I have a guy….”

“Shira,” Tava said, “you said he’s not into you.”

“It doesn’t have to be reciprocal! Everyone’s dead! Mom, Nona, Omi, Opa…. You don’t understand! Dad has to meet my husband, Tava, he has to be at my wedding, he has to be a grandfather to my children!”

Tava had pulled off the road, but she suddenly re-entered traffic and started briskly driving home.

“Wouldn’t it be fun to try on wedding dresses?” she said brightly.

I looked at her. Had my sister gone mad?

Suddenly something clicked.

“Let’s just buy them!,” I said, no longer crying.

“But how will we explain it to Dad?”

“I’ll say, ‘We have this idea, Daddy. For a really nice family thing to do. A photo shoot. It’s going to be really special….’”

“He’ll ask how much the dresses cost,” I said. We both started laughing.

“I’ll say, ‘Don’t worry, Dad. They’re on sale.’”

The talk went as we’d expected, and, in a sense, even better.

“I get it,” Dad said with a sigh. And then, heartbreakingly, “Okay.” It was the only time that he, even skirtingly, acknowledged to us that he was dying.

“So how much are they?” he asked.

“It’s a good deal, Dad.”

“Okay,” he said. “But promise me you’ll both get married under a tree.”

Earlier that year my co-worker had gotten married under a tree — it was just herself, her husband and their dog. A robot took the pictures. Dad loved that. He hated extravagant spending, but he loved celebration. He and my mother had had a small outdoor wedding at Bennington College. Mom made her own dress, and the only thing they served was dessert and champagne.

A wedding under a tree sounded good to both Tava and me. And it solved all the problems — who would walk us down the aisle, who would be there for family photos.

“You got it,” we said.

The following day my uncle agreed to stay with Dad so that Tava and I could go shopping. (My aunt had heroically left her work, home, and kids for weeks to be with Dad in Florida, and she was juggling everything electronically; my uncle was spelling her for a few days.) Tava tried on four dresses and I tried on two, but we spent over four hours in the store, playing with hats and poses, props and gloves. Kara — the manager of the store and our new dear friend — took photos, promising to discount the dresses and to come to the house to curl our hair and do makeup. It was epic, one of the most fun times that either Tava or I have had in our lives.

“Are you marrying each other?” a prying customer asked. “Actually,” we answered in unison, “neither one of us is getting married.”

One week later, we realized that we couldn’t wait for the seamstress — Wendy, another new fast friend — to take our dresses in, even though Kara had marked them “priority.” Dad’s health was declining rapidly, so we put on our unaltered dresses, Kara did our hair and makeup, and we set about trying to coax Dad on to the beach for a photo shoot — under a tree.

“I can’t do the beach. I’m not well enough,” he insisted. “I’m saving energy to get better.” It didn’t matter. Kara took two photos of all of us in the house, and we got the proof we wanted: Dad was at our weddings.

Shira, Rolf and Tava Sternberg.

I wore my dress to Barack Obama’s 2012 Inaugural Ball and to my house renovation party in Boston. And I have a priceless dress that I intend to wear not only at my wedding, but for the rest of my life.

Neither the dresses, nor the lives, are the ones that my sister and I would have chosen.

But they’re ours. So, yes. We said yes.

Shira Sternberg now lives in Tel Aviv, where she has developed a jewelry/fashion start-up with her sister Tava. Their business was inspired by their father, who used to give each of them a piece of jewelry every Valentine’s Day. Shira previously worked in politics.

- 6 Comments

July 15, 2014 by admin

A Woman’s Tashlich

It’s been 18 years since Marcia Falk, renowned Jewish feminist scholar and poet, brought us her groundbreaking The Book of Blessings: New Jewish Prayers for Daily Life, the Sabbath, and the New Moon Festival, a prayer book that not only uncoupled liturgy from patriarchal themes and imagery, but that gave women —and continues to give women —contemplative, gender-corrective ways to connect to the sacred.

It’s been 18 years since Marcia Falk, renowned Jewish feminist scholar and poet, brought us her groundbreaking The Book of Blessings: New Jewish Prayers for Daily Life, the Sabbath, and the New Moon Festival, a prayer book that not only uncoupled liturgy from patriarchal themes and imagery, but that gave women —and continues to give women —contemplative, gender-corrective ways to connect to the sacred.

In Falk’s new book, The Days Between: Blessings, Poems, and Directions of the Heart for the Jewish High Holiday Season (Brandeis University Press), she takes us further down the same spiritual path, reminding us that it is good to experience “the turning of the Jewish year” in nature, and that it is holy to immerse ourselves mindfully in endings and beginnings, in solitude and in relationships. “What kind of life will we live in the time we have?,” Falk asks. “Where in our life will we find purpose and meaning?”

Falk underscores that the period between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur (Aseret Y’mey T’shuvah) is intended to be a continuous devotional span; “ten days of meeting oneself face-to-face, opening the heart to change.” The word “between” in the book’s title palpates one of women’s special strengths: connection. Alas, we humans cannot stop time —we can’t make our six-year-old stay six forever, or bring a beloved deceased person back to life —but we can strive to be “fully aware of our connectedness to everything in our world,” and in that way live ourselves into “wholeness, serenity, and fulfillment.”

I asked Marcia if she would take a walk with me, for tashlich, along a river’s edge, using five poems from The Days Between as guideposts. (Tashlich is the ceremony in which Jews throw crumbs into the water to symbolize casting away our sins. In The Days Between Falk calls her new ritual Nashlich, which is gender-inclusive, “we will cast,” rather than Tashlich, “You [God, masculine] will cast.”) In the pages that follow here, she does this, helping me journey spiritually through her translations of poems by the well-known Hebrew poets Zelda and Leah Goldberg, and by the less well-known Yiddish poet Malka Heifetz Tussman. We begin our walk with Falk’s own poem, which revisions Micah 7:19, the biblical verse that opens the traditional tashlich. As we recite and then discuss the poems, they become cast as a prayer cycle. (I have distilled our conversation.)

Each of the poems, says Falk, “uses the archetypal sym- bol of water as revelatory, transformative, and redemptive.” Each “explores time, change, and mortality in the context of intimate relationships; and in each, water is given a voice. Zelda’s sea sings, Goldberg’s river hums, Tussman’s creek babbles.”

Reader: Take a walk with us. Put some crumbs in your pocket for tashlich, and find a serene place alongside water…water that eddies or babbles, water that cascades or crashes, water that hardly ripples. Enter “the between,” give voice to a conversation with your life, move forward along the meridian of deepening t’shuvah.

Hey, you! Come along, too.

CASTING AWAY

We cast into the depths of the sea our sins, and failures, and regrets.

Reflections of our imperfect selves flow away.

What can we bear,

with what can we bear to part?

We upturn the darkness, bring what is buried to light.

What hurts still lodge,

what wounds have yet to heal?

We empty our hands,

release the remnants of shame,

let go fear and despair

that have dug their home in us.

Open hands, opening heart —

The year flows out, the year flows in.

—Marcia Falk

MARCIA FALK: The High Holiday language is full of power and terror, and the verse from Micah that we recite for the traditional tashlich ritual is vivid, almost violent, asking God to hurl all our sins into the depths of the sea. I have a different image of the new year, of life and change. A wave comes to shore and then pulls back, there’s ebb and flow. Is it only our “sins” that we need to let go into the sea?

SUSAN SCHNUR: In the third stanza of Casting Away, you ask, “What can we bear?” Help me understand this.

FALK: For example, can I bear to live with the knowledge that I was mean to my child? Can I accept the “mean” parts of myself? Can I forgive myself?

SCHNUR: And then the poem asks, “With what can we bear to part?”

FALK: Yes. What can we let go of? I’m in the process of clearing out 20 years of clutter from my house, and I’m overwhelmed. I have to look at each thing: Can I part with this? Can I part with that? It can be hard to let go, to stop looking backwards. This is the time of year when we want to be able to walk into the new, but the old holds us hostage. Can we “release the remnants of shame,” let go the despair that has “dug [its] home in us”? The holiday is about perfecting ourselves —but not everything can be changed. Can we accept ourselves?

SCHNUR: Okay, here’s what I want to personally ponder in the palimpsest of this poem: This year, can I live less reactively in life’s ebb and flow?

FACING THE SEA

When I set free

the golden fish,

the sea laughed

and held me close

to his open heart,

to his streaming heart.

Then we sang together,

he and I:

My soul will not die.

Can decay rule a living stream?

So he sang

of his clamoring soul

and I sang

of my soul in pain.

—Zelda

FALK: Now we come to “Facing the Sea,” in which the speaker finds this Other —the sea —that is so unlike her. The speaker is quietly suffering, but the sea is noisy, laughing, bubbling over. Nature is completely alive, always alive —this noisy sea, embrac- ing us, holding us close.

SCHNUR: “My soul will not die”—they sing together about their shared immortality, that dying never conquers life. But the speaker remains so alone. The “Other” can only comfort us up to a point. Is that right?

FALK: The speaker lets something go —“the golden fish,” what- ever that is —and she is embraced. Then the speaker and the sea sing together, but their voices are very different. This poem, for me, is about being in pain and trying to find comfort.

SCHNUR: Here’s what I think I need to think about here: Can I learn to accept someone else’s imperfect love? Can I sing with the universe?

THE BLADE OF GRASS SINGS TO THE RIVER

Even for the little ones like me,

one among the throng,

for the children of poverty

on disappointment’s shore,

the river hums its song,

lovingly hums its song.

The sun’s soft caress

touches it now and then.

My image, too, is reflected

in waters that flow green,

and in the river’s depths

each one of us is deep.

My ever-deepening image

streaming away to the sea

is swallowed up, erased

on the edge of vanishing.

And with the river’s voice,

with the river’s psalm,

the speechless soul

will sing praises of the world.

—Leah Goldberg

FALK: This poem and the next are from a sequence by Leah Goldberg called “Poems of the River.” In the first poem here, a tiny blade of grass sings to the river. We all feel, at some time in our lives, that we’re “on disappointment’s shore,” that we are insig- nificant, “children of poverty”—a very touching phrase for me. But nature can comfort us —“the sun’s soft caress.” The river, in fact, takes our “images” —our faces, our selves —and deepens them.

When our mind quiets down, we get to sing “with the river’s voice, with the river’s psalm,” and we finally feel ourselves part of everything. Water here is wholeness, vitality, moving, streaming away to the sea.

So many of us experience ourselves as small—“even for the little ones like me” is such a poignant image. Why does the little blade of grass want to assure us that the river hums for us, too, lovingly? The blade of grass itself becomes our comforter.

SCHNUR: I love the rushing compassion of this poem. I want to say, “Yes, yes. Don’t leave without me!” This poem makes me want to think about the spiritual challenge of trust. Can I trust that everything will be okay?

THE TREE SINGS TO THE RIVER

He who carried off my golden autumn,

who with the leaf-fall swept my blood away,

he who will see my spring return

to him, at the turning of the year —

my brother the river, forever lost,

new each day, and changed, and the same,

my brother the stream, between his two banks

streaming like me, between autumn and spring.

For I am the bud and I am the fruit,

I am my future and I am my past,

I am the solitary tree trunk,

and you—my time and my song.

—Leah Goldberg

FALK: Ah! Here we find a less quiet voice, the self-possessed voice of the tree describing its relationship to the river. We don’t normally think of “blood” [in the second line] when we think of trees; we associate that with animal life, and when the animal is drained of blood it dies. The image is shocking, even suggestive of domination and submission: the river carries away the tree’s life-blood, yet the tree returns to the river again and again. Or, another way to look at it: perhaps the voice is defiant; it will not die, it will return, year after year.

There’s movement, a shifting of perspective. In the second stanza, the tree and the river are kin: the river streams, like the tree, between seasons. But in the last stanza the tree lets the river know that he, the tree, is solitary, whole in himself: “I am the bud and I am the fruit, I am my future and I am my past.”

Then, at the end, there’s a powerful reversal. The tree no longer addresses the river in the third person—as “he,” as “my brother”—but says, “you—my time and my song.” We aren’t solitary after all. There’s always “the other,” we exist in time, vis-à-vis the other. What is my voice if I’m just talking into the emptiness? I don’t have a voice unless I’m speaking to you.

SCHNUR: This poem breaks my heart. The tree is learning how to move from Martin Buber’s “I-It” relationship —separate, detached, full of defensive bravado—into an “I-Thou” relationship—of mutuality, of reciprocity, of touching interdependence. This challenge hits home for me: Can I learn to be more empathic and more yielding in my relationships?

from TODAY IS FOREVER

I stroll often in a nearby park —

old trees wildly overgrown,

bushes and flowers blooming all four seasons,

a creek babbling childishly over pebbles,

a small bridge with rough-hewn railings–

this is my little park.

It’s mild and gentle

in the breath-song of the park

and good to catch some gossip

from the flutterers and fliers.

Leaning on the railing of the bridge,

seeing myself in clear water,

I ask, Little stream,

will you tumble and flow here forever?

The creek babbles back, laughing,

Today is forever:

Forever is right now.

I smile, a sparkful of believing, a sighful of not-believing:

Today is forever.

Forever is right now…

—Malka Heifetz Tussman

FALK: This last poem is a little touch of mameloshn [Yiddish] in the middle of my book. Once again, water gives us its wisdom. The speaker talks to a stream, sweetly, as though to a child: “Little stream, tell me. Will you be here forever?” Human beings want to know! Are we going to live or die? What’s coming next?

And the creek laughs: Why are you asking such a question? This is what there is! “Today is forever.” The poor creek to have such a foolish disciple!

SCHNUR: Yes, how can we humans think about ourselves with- out thinking about the fact that we will die?

FALK: In every nature poem, there’s a dark thread. I like this poignancy; so much of Jewish liturgy doesn’t acknowledge it. I’m talking about sadness. There’s awe, fear, trembling, God is big, we’re small, all of that. The Kaddish: we exalt You, we enlarge Your name. How does that help one feel better? You’re sorrow- ing, you’re grieving, and what does the liturgy give you back? A big silence. Not much comfort. These poems by Jewish women offer us more.

SCHNUR: This poem asks the biggest question perhaps. Here go my last breadcrumbs into the water. How can we acknowledge life’s sadness? Can we do so and smile?

Sections in blue are excerpted from “The Days Between: Blessing, Poems, and Directions of the Heart for the Jewish High Holiday Season,” © 2014 by Marcia Lee Falk.

- No Comments

April 3, 2014 by admin

Reading “Dear Abby” in Massachusetts

Five years ago, when a new Jewish geriatric campus opened in Dedham, Massachusetts, I grabbed a friend and we started a “Dear Abby” group. I don’t remember how we got the idea. Since the beginning, we’ve met with the same 10 frail women, most in their 90s, every other Wednesday, 10:30 to noon. I call them “my ladies.” We just lost our first at 102. To prepare, I bake brownies, cookies, nothing fancy — I love to bake — and Dori cuts and pastes “Dear Abby,” and that’s the end of it.

“Dear Abby,” Dori reads. “When my neighbor walks her dog, it always does its business on my property….” I might ask my ladies, “When you were growing up, did you have a dog?” After another column, I might say: “Did you know anyone who had a gay child?” “Anyone in your family get divorced?” The dirtier the better. When the man has an affair, or there’s a little adultery: “If you saw your girlfriend’s husband, would you tell?”

My ladies are extremely opinionated. Extremely. It’s not “I think.” It’s “I know.” They criticize one another, bickering back and forth, and are very caring, very protective. Sometimes it’s “Real-Life Dear Abby”: A woman in the group who’s 100, her son got divorced and she’s still close to her daughter-in-law, which infuriates her son. “What would you do, Vivian?” I ask. When Dori was going on vacation with her family, her college-aged son wanted to invite his girlfriend. “Should I get another room?” “Is it appropriate?” My ladies always have what to say. Is their advice good? Not really.

“Dear Abby, when my husband and I eat out, he insists on…” My ladies are reminded that they miss things. Like Chinese restaurants. So twice a year, at Hanukah and in the summer, we bring them take-out. You’d think we were bringing gold.

“Dear Abby, my brother-in-law is an alcoholic…” One lady pipes up, “I used to like a cocktail once in a while.” Another lady: “Well, you can drink here, you know.” “Yeah, I’m sure you could have a drink if you wanted it.” “I don’t want to drink alone.” “Jayne, you always come in the morning. What if you come in the afternoon without the cookies?” They all got doctors’ notes, we came with a cooler, and we had wine, crackers, and cheese. Boy, they drank!

The “Dear Abby” part is kind of inconsequential. It’s the questions you ask after, you have to pull out from them. “Did you allow this when you had a teenager?” I do a lot of gatekeeping. “You have to wait your turn.” Some of them can go on forever. “That’s a great story, Diane, but let’s hear from Ruthie now.” A “Dear Abby” group would be a great way to integrate a new resident.

I love to hear my ladies talk about their children; you can tell what kinds of mothers they were. Some are boastful, sometimes their kids come; their kids are older than me. We do a lot of screaming now. Over the years, it’s changed. “I lost my hearing aid!” “What? What?” We read “Dear Abby” more slowly. They need shouting.

My husband had cancer for six years, and when he recovered — my ladies prayed for him for so long! — I made him come with me. He said, “I love you very much, Jayne, but you talk like they’re really with it. Half of them are sleeping.” “Yeah, but they wake up. They’ve gotten old.” So you wake them up and you say, “What do you think?” A neat little lady, drop-dead gorgeous, she’s failing, not doing well, she falls asleep and I say, “Hey Margie, get up.” We celebrate their birthdays; we bring little trinkets from the Dollar Store.

It doesn’t matter what you talk about, what matters is conversation. I just know this has made a huge difference in my ladies’ lives. I’ve done substantial volunteer work in my life, but this is one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever engaged in.

My workplace has wanted me to up my hours, but there are certain pieces of my life that I am not willing to give up, like my ladies. I will never give up the ladies. It’s weird how special this has become to me.

Jayne Lampert volunteers at Newbridge on the Charles, a part of Hebrew SeniorLife, and is the Director of Annual Giving at a social service agency in Massachusetts.

- No Comments

December 8, 2008 by admin

The Shekhinah Sh’ma: Six Little Words to Shake the World

Susan Schnur: Ariadne, so this Shekhinah Sh’ma popped into your mind full-blown?

Ariadne lieber: Yes. I was praying, and I often pray feeling half-alienated. Here’s the traditional Sh’ma: “Hear, O Israel: the Lord our God, the Lord is One. Blessed be His glorious kingdom forever and ever.” Ichhh…. The words “Lord,” “His,” “glorious kingdom” — I don’t relate to lords and kingdoms. Spiritually, this isn’t what I need to say. For goodness sake, it’s the 21st century.

Schnur: Your doctoral dissertation was on the motif of joy in biblical prophecies, and you’re a spiritual intuitive. This makes you an interesting pray-er. Can you walk us through these six little words?

Lieber: Well, the first two words are unchanged — “Sh’ma Yisrael” — but I certainly don’t think of translating them as “Hear, O Israel,” which is the traditional rendering. That has an administrative sound to me and feels patronizing and anti-me. “Listen, Israel” is much stronger, more open, it’s not somebody trying to tell you — trying to tell the one who’s praying — what to do. It’s a process; listening is deep. It’s active. “Listen” means “Stop for a moment. Become absorbed in this.” The pray-er will come up with something. “Listen” — I’m getting my own attention here.

Schnur: Paying attention is a spiritual act. It’s like that magnificent Denise Levertov poem about marriage. One partner says to the other, “You have my attention” — what an exquisite thing to say to the one you love. “You have my attention: which is a tenderness, beyond what I may say.” I’ve done wedding ceremonies where I adapt this poem into nuptial vows.

Lieber: “Listen, Israel” is also someone else talking to the ancient Israelites, myself among them. It’s the eternal me, the big me. It’s Everyjew. It’s Frankie’s “the we of me” from Member of the Wedding.

Schnur: And Walt Whitman’s “I contain multitudes….”

Lieber: Right. Embracing everything. “Sh’ma Yisrael” is an invitation: “Okay, I’m listening, I’m excited. What do you have to say?”

Schnur: Well, the next two words: “Ha-Shekhinah b’kirbainu” — that God’s presence or indwelling is in our inmost being, is among us.

Lieber: Yes. The Shekhinah is a female naming of God, it’s the term for divine immanence; that is, the God within us, circulating all around us, the God in everything. It’s not the God over us, it’s not that Lord God on a throne.

Schnur: The Shekhinah dwells with us.

Lieber: I don’t like the word “God.” It’s a dry word. It’s cold. It doesn’t do anything for me. It has a masculine sound in my ear. Gott. Sort of military. A choppy, cut sound. To be honest, it repels me. Shekhinah takes me further, to a different place. Shekhinah is a spirit, not an image. It’s a feeling of divinity all around you. A presence you can’t deny, an indwelling. In Chinese, it’s your Qi [pronounced “chee”]. And I like “the” Shekhinah — it’s an honorific that includes us.

Schnur: How are you with “the Lord our God” — “Adonai Elohainu” — in the original Sh’ma?

Lieber: It’s so distant. It’s out there. Where is this guy? Who cares? There’s nothing personal about “the Lord our God.” It doesn’t locate godliness. Somebody outside of us — a male, maybe Moses — is ordering us (“Hear, O Israel!”) to hear that the Lord is our God. Ughh. It’s unilateral, uni-directional. My “Listen, Israel” is very internal, it’s preparing us for something beautiful, something whispered and inclusive and complete, something so holy.

Schnur: It’s a mean and frightening world out there, a mutilated world. It’s imperative that humanity locates the divine within itself.

Lieber: Within Herself. Now we come to the fourth word, the fulcrum word: “b’kirbainu” — within us, among us, in our midst, in our inmost being. Wow. We’re expressing this to each other. “Hey, it’s within us!” It’s a revelation. No one told us this before, that it’s within us. At Sinai, they made a mistake. They really wanted to see a God. I think the word “b’kirbainu” came to me from the prophet Zephaniah: “God is in the midst of thee” is the standard translation [Zephaniah 3:17].

Schnur: But Zephaniah goes on to call God the “Mighty One who will save.”

Lieber: Whoa. That does not at all take us where we want to go! We need Oneness, not a One that’s Other, who “saves us” from outside of us, who is a separate entity. We’re part of the One. I don’t want a God who’s making something out there, who “forms light and darkness” — a God outside. I am part of God. I don’t care if God is male or female, or male and female, what I care about is that I am part of God.

Schnur: I need to go back to the uni-directional God for a moment, to the God who has a unilateral relationship with us. What if our relationship with that God were really reciprocal — if that God gets changed by our commitment, by our listening? If listening makes us equal? I need to quote the whole Levertov poem, to re-title it “Sh’ma”:

You have my

attention: which is

a tenderness, beyond

what I may say. And I have

your constancy to

something beyond myself.

The force

of your commitment charges us — we live

in the sweep of it, taking courage

one from the other.

Lieber: Oh, the idea of God taking courage from us is just amazing. There is no God without us; God needs us. When I was working on my dissertation, I found that the biblical God didn’t always know what God was supposed to do. In the book of Exodus, God needs Moses’ help to find His/Her position. We’re still watching the process of God’s growth and development, of God’s maturation. It hasn’t ended. My Sh’ma certainly doesn’t declare that God is complete.

Schnur: But the last word there — “Ahat” — certainly feels summative.

Lieber: Yes, this is the word that started the Shekhinah Sh’ma for me. It’s the feminine form of the word “one.” “The Shekhinah is One.” And what’s wonderful about it, as compared to the masculine form of the word, is that it starts with the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet and ends with the last letter of the alphabet. When I first realized this, while sitting in the library, I was beaming. I’m still beaming!

Schnur: It makes you happy.

Lieber: In the library, I was like a holy fool, a meshugeneh, talking to myself and the holy Hebrew letters. We are the beginning and the end. No matter what you do, it comes back to a beginning and an end. “Ahat” ties up the package, the doxology. And this alpha-to-omega word, in the feminine, happens to mean “one.” And we run all over the place shouting these words: We teach them to our children, and bind them upon our arms and heads, and write them on our doorposts. We put them everywhere so we don’t forget.

Schnur: “Listen, Israel, the Shekhinah is in our inmost being [is among us], the Shekhinah is One.”

Lieber: Yes. I don’t want the traditional Sh’ma, the traditional declaration of faith, posted everywhere. It takes our freedom away; it’s belittling. It severs us from ourselves. Women don’t want a big God up over us. The Shekhinah Sh’ma meets women where they already naturally are: in dialogue, in reciprocity, in inclusive and eternal oneness. This Sh’ma affirms what’s already ours: the prayer within.

Schnur: The inside/outside/everything/the earth/all of it.

Lieber: The “aleph” to “tof ” — the A to Z. The One.

- No Comments

March 15, 1998 by admin

The Womantasch Triangle

The figures of Vashti and Esther, clearly in origin full-moon prespring relatives of the ancient mythological life cycle goddesses, come down to us, in the Book of Esther and in rabbinic midrash, so disfigured and devalued that it is hard to know how to begin resurrecting them.

But let’s start with Harvard psychologist Carol Gilligan, whose research shows us that females’ self-esteem is highest before puberty, but then we turn into women, males enter our consciousness, and it all goes to hell.

FIRST VASHTI

In the Book of Esther, Vashti is that pre-pubescent Gilliganesque girl—self-confident and self-determining (who does what’s right for herself and says “no” to the boys), but she is punished for her assertiveness, and she therefore “grows up,” as it were, into Esther, a female who submits much more graciously to patriarchal domination. The rabbis take an almost erotic delight in hating Vashti and they kill her off (Lilith redux); the midrash lasciviously describes Vashti’s head “brought before the King on a platter.” Ahasuerus is neatly freed up to start all over again with the new, young trophy wife named Esther.

So where does Vashti, the dead girl, go? The Book of Esther has at its thematic core the same ancient fertility myths in which one goddess or another serves metaphorically to explain winter’s death and spring’s resurrection. If Vashti were, for example, Demeter’s daughter Persephone (instead of being Esther’s disowned ‘daughter’), she would go down to Hades and then eventually rejoin her mother on Earth. If she were the young Inanna, she would remove herself from ordinary life (the Megillah’s harem is a distorted echo of this), and descend into the Underworld, where she would sacrificially rot on a peg, be transformed, and return to Earth a larger, wiser, more creative goddess—no longer patroness of fertility alone, but also of death and resurrection, the new ruler of the now-conjoined Earth, Sky and Underworld. From the Underworld, one returns bearing gifts—not shalach memos, mind you, but gifts only acquirable down under. Wisdom, Letting Go, Awe and Gratitude.

Inanna’s “rotting” is an initiation into understanding the inexorable cycle of life—that each one of us is born, ages and dies, only to be born again from the earth in some new form—maybe as humus, maybe through our children. Death is a pan of life. Vashti, in parallel fashion, makes a sacrifice in Hell (in this case, the palace) too: she says “NO”—understanding full well that she will suffer terrible consequences. But unlike Inanna, the wisdom Vashti derives from her self-determination is confiscated by the text and never conveyed to her ‘daughters.’ Vashti’s resurrection is that she exits, stage left, only to be replaced in the next act by a freshly minted queen with a new name and no memory.

Let’s imagine, say, that Vashti had been a part of the ancient Greek women’s ritual of the Thesmophoria. She would not, then, have resurfaced solely as a “head on a platter” at the King’s supper club; rather, she would have encountered an “older sister” in the Underworld, someone who came before her and is wiser, and who inducts her into wisdom. But the Megillah keeps its significant women isolated from one another, erasing any suggestion that there might be significant female interaction. (In Esther’s case, of course, the text goes so far as to make her an orphan.) Hardly anything, as we know, is as scary to patriarchal men as two women alone in a room together. Vide: Lilith and Eve, Sarah and Hagar.

DANCING NUDE

Queen Vashti is summoned by the King to dance nude, in a clear bastardization of fertility myths. Queen Inanna, for example, to jump-start spring’s fertility, herself summons King Dumuzi, ordering him to “plow my vulva!”

Vashti’s King, on the other hand (not, like Dumuzi, epithetically called “caresser of the navel, caresser of the soft thighs”) functions on a stage with no mythological overtones, and the text Vashti finds herself in—a repudiation of Inanna’s—seems to take particular sadistic pleasure from disempowering and humiliating her. Vashti’s agency is reduced to her ability to say “NO” when the King orders her, a Playboy bunny, to strip before a mob of drunks at his house party.

What’s in it for Vashti? She dies—the assertive girl-child dies, the one who is not afraid to be assertive, not afraid to displease the males. The Megillah kills off not only Vashti, but the whole cycle—death, rotting, rebirth, the whole awakening, empowering experience. It’s a deliberate theft, a humiliation. She doesn’t get to re-emerge as a woman. There ain ‘t no journey at all!

To borrow a phrase from the writer Deena Metzger, “In a sacred universe, she [Vashti] is holy; in a secular universe, she [Vashti] is a whore.”

MOTHER AND DAUGHTER

The Demeter-Persephone myth expresses an interesting cultural compromise: the emotional centrality of mother daughter bonds (hence Persephone gets to spend a part of each year with Demeter) and the inevitable severing of that bond when the girl grows up. (Persephone, raped by Hades, eats a seed—ahh, shades of the hamantasch!—and must stay with Hades, Lord of the Underworld, during the other part of the year.)

In the Megillah. however, Vashti is, of course, punished, and is not allowed—ever—to bring her laundry home to Mama Esther’s house. Esther’s early debutante world coarsely compartmentalizes women, too. Like cattle in a cattle chute, each girl arrives from Harem A, spends one night with King Ahasuerus (chapter 2:14) and then returns, via chute, to Harem B.

Keeping mothers and daughters apart finds resonance in the story of Zeus and Metis. The pregnant Metis gets tricked by Zeus into becoming small, at which point Zeus swallows her. When the baby, Athena, grows to adulthood, she emerges from her father’s head—with no sense that she had ever had a mother who might have taught her anything, or, in any way, ‘birthed’ her. In this way, women’s stories, too, get ‘swallowed’ by patriarchal ones like the Megillah. Vashti is ‘swallowed’ up by the story—to keep Esther from picking up any bad habits.

JUST SAY YES

Who among us, as a teenager, hasn’t had Vashti’s experience of saying “NO” to a boy and getting punished for it? Really, though, what if Vashti had said “YES”—follow that storyline out. Poor Vashti was double bound; it’s lose/lose.

And a final Vashti question: What if the text had let her grow up? When Vashti die.s, we girl readers die with her, every goddamn Purim—warned not to take good care of ourselves. Frozen in Vashti-land, banished. What if we let Vashti talk, follow her story? What if we imagine what she might have gone on to do besides getting transmogrified into Esther? What if we let her become herself!

In a sacred universe, she would not be treated like an object by abusive men, she would not be forbidden access to her sister, mother, daughter, be forbidden to take her trans formative journey. In a sacred universe, she would be holy.

THEN ESTHER

Purim’s origins, scholars generally agree, derive from an ancient full-moon pre-spring Persian holiday; Esther is descended from the Babylonian Ishtar (who derives from Inanna) and Mordechai from the Babylonian Marduk. (These gods are allied against the Elamite goddess, Vashti, and the god Humman, that is, Haman.) Ishtar, a universal life cycle goddess, also rules the morning star and evening star, so Esther’s Hebrew name, Hadassah, means “myrtle,” which has star-shaped flowers, and leaves which are vulvate or boat-shaped, again that fertility symbol that goes back over 30,000 years to engravings on cave walls.

Ishtar was a virgin-warrior, and Esther can be seen as a translation of that—compared to Vashti, she’s a virgin, and she’s a warrior for her people. Ishtar is also the moon goddess, her story described in the moon’s phases (for example, an absent moon depicts Ishtar losing her clothes on the way to the Underworld). In the Megillah, the Queen’s being ordered to appear in the King’s “underworld” nude is a corruption of this.

In the process of mythological assimilation, Ishtar and Isis, over time, take on each other’s traits. Esther’s capacity to overturn the Jews’ fate (the death warrant fatwa put on Jewish heads by Haman) derives from Isis’s famous capacity to keep death away from her faithful followers. And Isis’s well-known boast, “I will overcome Fate,” which she proceeds to do, is echoed in Esther’s valiant statement (“If I perish, I perish,” chapter 4:16) which the Queen utters when she appears before Ahasuerus without his royal permission. Esther, like Isis, overcomes fate, because the King, against the odds, stretches out to her his golden scepter, thereby allowing her to live. For many women, this part of the Megillah tells a deeply moving Jewish story about female courage.

But unlike the goddess Ishtar, who has power in her own right just like a male god, the less ancient Esther (like the Virgin Mary, who can intercede with God but who isn’t God) can only intercede with the King, but has no power for herself.

SEPARATED AT BIRTH

Gerda Lerner, in The Creation of Patriarchy, argues that, over time the “Great Goddess, whose powers are all-encompassing (mother, warrior, creator, protector), loses her unified dominion, and becomes split off into separate goddesses.” Vashti and Esther are heiresses to this split.

Of course, the split becomes a male projection. Men seek the erotic from one source (Vashti, the whore, the mistress), and nurturance from another (Esther preparing banquets at the stove mother, wife, madonna). Women live with this split, and we thus lose the ability to connect our own sexuality, our own bodies, to the sacred, to the universe.

For women today, the real loss is not as much the suppression of female rites, as it is the deprivation of consciousness. In other words, it is the rare woman these days, in hating her body, who even thinks to make a connection between her body and the Earth’s body, her breasts, vulva, thighs and the Earth’s, her seasons and cycles and the Earth’s. This is a big loss, both in terms of our self-esteem and sense of well-being, and in relation to women’s sense of spiritual connection.

Inanna’s sacred erotic experience which brings on April’s showers and May’s flowers devolves, in the Book of Esther, into Vashti as whore. Queen Esther becomes adored by the rabbis, but Vashti gets split off as a dirty body, coarse nature.

If you have any doubts about the propagandistic effectiveness of Vashti’s utter demonization in rabbinic misogynist texts, here’s an experiment. This Purim at synagogue, count how many girls dress up as Vashti (zero; just a guess). Ask the little Esthers why they aren’t dressed up as little Vashtis. Write down their answers. Ask what Vashti did to make her so “bad.” (My daughter’s friends generally reply that Vashti “said NO to the King.” We discuss whether it is bad to say ‘NO’ to males. Does that mean you should say ‘YES’ to males? Etc.) Invite all the little Esthers to your next Rosh Hodesh event, and help them burn all their old misguided answers in a big black cauldron. Call the event “We’re All Witches” (all right, “We’re All Sisters” will do).

ESTHER’S ANOREXIA

As anyone who has been on the idealized (vs. the devalued) side of the madonna/whore split knows, it’s no picnic being Esther, either. The male rabbis love her (ostensibly because she saved her people), but then the rabbis piggyback other virtues on to the courageous lass just to confuse us: Esther’s tiptoeing wifely style, her dependence on the King, her title of ‘prophetess’ (which is very odd. given that the Megillah is a highly secular book).

Most creepy of all, though, is the rabbis’ lewd, peeping Tom’ish interest in exactly how Esther is beautiful. In the midrash, they literally quantify and rank her beauty vis-a-vis other Jewish women, and descriptions of the exact quality of Esther’s sexual appeal take up many pages. The rabbis sound remarkably like tho.se classic fathers of anorexic girls who feel compelled to comment to their daughters, “You’ve gained weight at college,” or “Your roommate’s a knockout.” These contemporary Esthers, as we all know, get their sad revenge.

EARLY SPRING: HEALING THE SPLITS, CIRCLING BACK

they are journeysVashti and Esther, of course, are in coalition, not opposition. The journeys of females—Isis, Demeter, Inanna—are not journeys to find answers, they are journeys to gather something together, to make things whole. Even the Shekhina, the female aspect of the Jewish God, gathers up lost souls. Isis gathers up the parts of Osiris. Demeter searches for her daughter. Our themes, as contemporary women, are the same: to restore something that has been . separated, to reconnect body and soul, to reunite Vashti and Esther, to integrate and reclaim the feminine that has been lost or abandoned in human history.

Esther must circle back to carry Vashti across the threshold into telling her story. And it is not just the girl’s story that must be retold and reheard, it is also our mothers’ stories— Vashti, Esther, and their mothers’ stories, Ishtar, Demeter, and all the rest.

To be nourished with only male images of what’s female and what’s divine and what’s Jewish is to be badly malnourished.

So let us reclaim the womantasch, and tell the whole Megillah.

- 1 Comment

Please wait...

Please wait...