Tag : Shayna Goodman

March 25, 2014 by Shayna Goodman

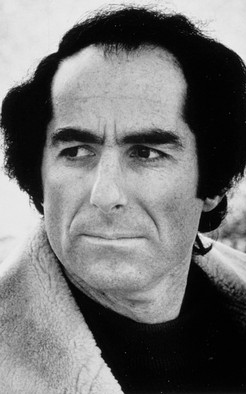

Why I Did Not “Like” Philip Roth’s New York Times Interview

Last week, while scanning through my Facebook newsfeed for its usual mix of engagement announcements, serious news and Buzzfeed lists, I noticed that several of my male Jewish friends had shared the recent interview Philip Roth gave to Daniel Sandstrom, the editor of the Swedish newspaper, Svenska Dagbladet, reprinted in the New York Times Book Review. “If even one of you reads this absurdly perfect Q&A with Philip Roth, my entire engagement with social media has been worthwhile,” someone posted. Other men “liked” it. No one mentioned the troubling and decidedly imperfect parts of the interview about misogyny.

Last week, while scanning through my Facebook newsfeed for its usual mix of engagement announcements, serious news and Buzzfeed lists, I noticed that several of my male Jewish friends had shared the recent interview Philip Roth gave to Daniel Sandstrom, the editor of the Swedish newspaper, Svenska Dagbladet, reprinted in the New York Times Book Review. “If even one of you reads this absurdly perfect Q&A with Philip Roth, my entire engagement with social media has been worthwhile,” someone posted. Other men “liked” it. No one mentioned the troubling and decidedly imperfect parts of the interview about misogyny.

“In some quarters it is almost a cliché to mention the word ‘misogyny’ in relation to your books. What, do you think, prompted this reaction initially, and what is your response to those who still try to label your work in that way?” Sandstrom asks. Roth responds: “It is my comic fate to be the writer these traducers have decided I am not. They practice a rather commonplace form of social control… In some quarters, ‘misogynist’ is now a word used almost as laxly as was ‘Communist’ by the McCarthyite right in the 1950s — and for very like the same purpose.” –for the same purpose? As Roth must be aware, the McCarthyite right was responsible for silencing, imprisoning and disenfranchising its victims. Surely Roth could not be comparing the intent of his feminist critics with McCarthyites. But as a friend of mine said, why should I be surprised by this response? To mention the word “misogyny” in relation to Roth is a cliché for a reason: because he refuses to acknowledge the possibility of problematic content in his work. It’s worth noting that Roth often gives flippant or provocative responses in interviews. But the idea that Roth views feminist criticism as erroneous and “ a rather commonplace form of social control” is surprising nonetheless.

I have enjoyed many of Roth’s novels. I have even appreciated the more controversial sections of his novels concerning stupid, sexually manipulative and emotionally unstable seductresses—the thought that these descriptions were offered from the point of view of a faulted protagonist eased my sense of guilt as a feminist reader. As Roth himself says in this interview:

“Whoever looks for the writer’s thinking in the words and thoughts of his characters is looking in the wrong direction… The thought of the novelist lies not in the remarks of his characters or even in their introspection but in the plight he has invented for his characters.”

- 5 Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...