by Shayna Goodman

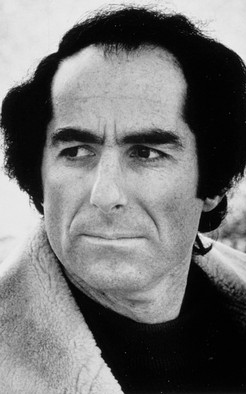

Why I Did Not “Like” Philip Roth’s New York Times Interview

Last week, while scanning through my Facebook newsfeed for its usual mix of engagement announcements, serious news and Buzzfeed lists, I noticed that several of my male Jewish friends had shared the recent interview Philip Roth gave to Daniel Sandstrom, the editor of the Swedish newspaper, Svenska Dagbladet, reprinted in the New York Times Book Review. “If even one of you reads this absurdly perfect Q&A with Philip Roth, my entire engagement with social media has been worthwhile,” someone posted. Other men “liked” it. No one mentioned the troubling and decidedly imperfect parts of the interview about misogyny.

Last week, while scanning through my Facebook newsfeed for its usual mix of engagement announcements, serious news and Buzzfeed lists, I noticed that several of my male Jewish friends had shared the recent interview Philip Roth gave to Daniel Sandstrom, the editor of the Swedish newspaper, Svenska Dagbladet, reprinted in the New York Times Book Review. “If even one of you reads this absurdly perfect Q&A with Philip Roth, my entire engagement with social media has been worthwhile,” someone posted. Other men “liked” it. No one mentioned the troubling and decidedly imperfect parts of the interview about misogyny.

“In some quarters it is almost a cliché to mention the word ‘misogyny’ in relation to your books. What, do you think, prompted this reaction initially, and what is your response to those who still try to label your work in that way?” Sandstrom asks. Roth responds: “It is my comic fate to be the writer these traducers have decided I am not. They practice a rather commonplace form of social control… In some quarters, ‘misogynist’ is now a word used almost as laxly as was ‘Communist’ by the McCarthyite right in the 1950s — and for very like the same purpose.” –for the same purpose? As Roth must be aware, the McCarthyite right was responsible for silencing, imprisoning and disenfranchising its victims. Surely Roth could not be comparing the intent of his feminist critics with McCarthyites. But as a friend of mine said, why should I be surprised by this response? To mention the word “misogyny” in relation to Roth is a cliché for a reason: because he refuses to acknowledge the possibility of problematic content in his work. It’s worth noting that Roth often gives flippant or provocative responses in interviews. But the idea that Roth views feminist criticism as erroneous and “ a rather commonplace form of social control” is surprising nonetheless.

I have enjoyed many of Roth’s novels. I have even appreciated the more controversial sections of his novels concerning stupid, sexually manipulative and emotionally unstable seductresses—the thought that these descriptions were offered from the point of view of a faulted protagonist eased my sense of guilt as a feminist reader. As Roth himself says in this interview:

“Whoever looks for the writer’s thinking in the words and thoughts of his characters is looking in the wrong direction… The thought of the novelist lies not in the remarks of his characters or even in their introspection but in the plight he has invented for his characters.”

But the plight that Roth has invented for his protagonists, over and over again, is the plight of “masculine power impaired” (as Roth himself explains it). “As I see it,” he explains in this interview, “my focus has never been on masculine power rampant and triumphant but rather on the antithesis: masculine power impaired.”

The concept of “masculine power impaired” is faulted from the beginning—from a feminist perspective, masculine power should be impaired. In his novels, Roth often writes about masculinity impaired by female sexuality; and this reveals something big and troubling about Roth’s attitudes towards women.

Impaired masculinity is a recurring theme in modern Jewish literature—the subject of college seminars and term papers. Scholars such as the historian, Daniel Boyarin have argued that historically, Jewish men have been the emotional victims of the collision of Western conceptions of masculinity with the prototype of the Jewish male scholar. What Roth makes clear in his creation of menacing seductresses, is that women have been as much to blame for Jewish emasculation as tall, athletic, gentile men. Often times in Roth’s novels, the protagonists’ unraveling is the result of an interaction with women such as the brainless model, Mary Jane Reed (“the Monkey”) in Portnoy’s Complaint or the curvaceous, reformed anti-Semitic Pole, Wanda Jane Posseski of Operation Shylock. These women lure the male protagonist, defenseless against his own lust, into further self-destruction and self-loathing.

Some readers of Roth argue that he is of another generation, that he is an 81-year-old man with antiquated views of gender relations, and the public discussion of his misogyny is at this point just as antiquated. But his novels, like any great works of art, have lasting popular appeal. Roth’s fiction portrays humanity (not only manhood) as impaired by ego and passion. And even today, young people continue to read and discuss his novels on social media. While Roth’s views might be antiquated, his books have not lost their resonance with contemporary audiences.

But even while we can appreciate Roth’s writing, we should not dismiss his sexism as harmless and antiquated. We should not make light of Roth’s evasion of Sandstrom’s question about misogyny and the ludicrousness of comparing feminist criticism with McCarthyism. These comments do not diminish the value of his work; but they do help us to contextualize his art within a specific cultural time and place in which sexism was met with greater tolerance.

Feminism does not seek to silence those who struggle with traditional gender roles and feelings of male inadequacy. These issues should be explored in Jewish literature in a way that does not blame and alienate women. Roth belongs to a generation of post-war writers known for their preoccupation with the male ego. This generation defined what we think of as American Jewish literature—but it should not be its lasting legacy.