Tag : review

November 13, 2019 by Amy Stone

Our Reviewer’s Picks at the Other Israel Film Festival

Women directors are no longer a big deal, so take note of these four women-

made films worth seeing no matter who made them. Check the OIFF website for

additional films and events.

Breaking Bread (Director Beth Hawk; JCC Sunday, Nov 17, 4:30 pm) At last, food as the bridge to understanding in a film

festival that’s hungry for hope. Dr. Nof Atamna-Ismaeel was first Muslim Arab to

win Israel’s Master Chef competition. The microbiologist from an Arab town in

northern Israel is using her food festival for social change.

Border of Pain (Director Ruth Walk; international premiere JCC Wednesday,

Nov. 20, 6:15 pm) Food and medicine, two ways

to break down walls. The sturdy, head-covered Gaza and West Bank women

determined to get permission to enter Israel for life-saving hospital care. The

Israeli doctors and volunteers who are part of an elaborate health care

bureaucracy knitting together Israel and Palestinian Authority ministries. And the

amazing Dalia Bassa, health coordinator for Israel’s civil administration. Blonde

hair, pink shirt, driving from border crossings to hospitals, her cell phone never

stops ringing.

- No Comments

April 2, 2019 by admin

Women’s Anger—Derided, Feared and Threatening

Recently, at a gathering populated mostly by women, I made the mistake of telling someone I had just met that I wouldn’t describe myself as angry about the state of things. “I’m scared,” I told her, “and confused, and hypervigilant, but I don’t think angry is the right word.”

I wouldn’t blame her if she didn’t want to keep talking to me after that, because if you’re a feminist to say you’re not angry with how the world is right now is kind of a deranged statement.

I recognize my own anger, or at least I thought I did. It’s churning, relentless, repetitive, powered by the memory of whatever emboldened it in the first place. Yet what I’ve been feeling most often these days is a dullness, like I’m dragging myself around, uselessly. The word that comes to mind to describe this feeling, and its associated behavior, is “lazy,” but since finishing Rage Becomes Her (Simon & Schuster, $27) by Soraya Chemaly—one of a spate of new books that address women’s anger and frustration—I’m doing some reconsidering.

Rage Becomes Her is more than an invitation to interrogate our own anger— it’s an imperative to do so. In chapters that examine the reality of what it’s like to be female, readers are delivered a litany of sexism and injustice to be angry about and offered the chance to decide how they feel about it. Does it provoke anger? If so, what does that anger look like?

“We make our rage small,” writes Chemaly. Women’s anger is so derided, so feared, so threatening, that women have learned to trim and squash and manicure it until it’s all but imperceptible. She recalls, when she was a child, watching her mother, a seemingly perfect maternal figure and wife, hurl her wedding china off the veranda. This was how anger was illustrated in Chemaly’s childhood—by this singular incident. There was never an explicit discussion about her mother’s anger, or what Chemaly’s own relationship to anger should or could be.

Women’s anger takes forms that are molded by how we’ve been punished for expressing it. Because our anger is so often dismissed, as when we’re “gaslit” and told we’re being hysterical, it can turn into anxiety and depression, shame, and physical pain.

“Rumination,” Chemaly reveals, “is how many women and girls learn to deal with their anger.” For me (a ruminator—ask me about all the things I won’t let go of), it’s facts like these that make Rage Becomes Her unique and worthy of mention in the crowded field of recent writing on anger. It’s not just a book about why we should be angry, but about the shape of anger, its texture. It wants us to understand rage and what it can be, so we can better connect with our own.

Towards the end of the book, in a chapter entitled “A Rage of Your Own,” Chemaly writes that, “As women, we are even more judgmental about other women’s violation of rules about anger than men are.” When I worked in Jewish organizations (populated mostly by women), I was often the only person in the room bringing up certain issues—heteronormativity in Jewish spaces, for example. It wasn’t just the frustration of having to remind people constantly that not everyone was or should be the same, but the concern that I was being judged for my outspokenness, that the clock on being tolerated, let alone heard, was running out. Carrying all of this at once was exhausting, and I became angry at myself for daring to feel exhausted, instead of being eternally patient (not a healthy expectation).

Women do evaluate one another on our anger. Are we too angry? Are we rocking the proverbial boat for no reason? (No.) Are we putting whatever we’ve already gained in jeopardy with our anger? How should anger look so that we don’t do this? Are we angry enough? Is that even possible? (No.)

After finishing Rage Becomes Her, I thought again about that awkward encounter at the party. The conclusion I’ve come to, of course, is that I am angry. It feels sludgy and plodding, but it’s more familiar than I realized. I fell into this very well-designed, strategic trap of thinking too much about what something should look like, instead of letting myself come around to what I know is true. Chemaly’s book reminds us of the importance of excavation and reimagination of our anger, and that with its power, change is inevitable.

Chanel Dubofsky writes fiction and nonfiction in Brooklyn, NY.

- No Comments

April 2, 2019 by admin

The Matron Saint of Israeli Feminism

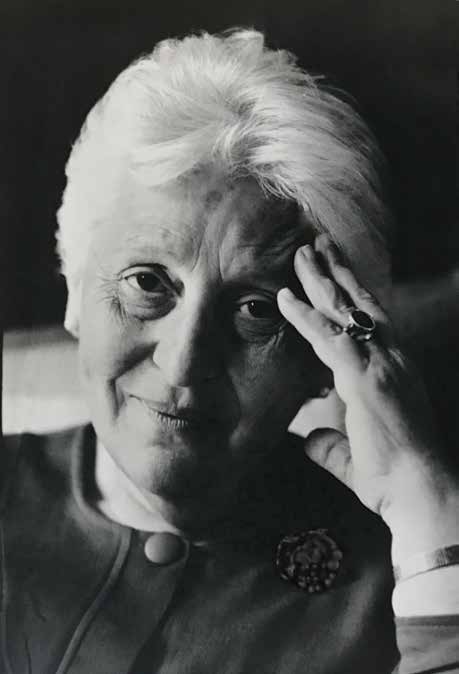

Photo: Joan Roth

Reading Alice Shalvi: Never a Native was like discovering a kindred spirit. From the moment I first picked it up, I carted the heavy hardbound volume around with me everywhere, stealing glances at the cover photograph of kindly, white-haired Alice smiling pensively back at me—in synagogue, where I read her book behind the mehitza; in the classroom, where I tore through a few more pages while my Talmud students learned in hevruta; and in the theater where I’d taken my children to see a play, my cell phone flashlight illuminating the page. “Ah yes, I know where you are, I have been there too,” Shalvi seemed to be saying to me wherever I toted her around.

Shalvi, whose memoir (Halban Press, $18.99) was published just before her 92nd birthday, knew the synagogues and study houses and theaters of Jerusalem intimately, though she too, as she avows, was never a native. Alice Margulies was born in 1926 in Essen, Germany, and fled to London with her parents and older brother eight years later. Shalvi had already taught herself to read in her native German by age four, and she quickly taught herself English as well so she could devour the novels of Lewis Carroll, Louisa May Alcott, E. Nesbit, and Arthur Ransome. In her primary school she was frequently asked by her teachers to entertain the class by reading aloud while the other pupils learned to sew, a skill she consequently never acquired. (And here I flipped to the front cover and smiled back at Alice, because I shared her predicament—I never learned to sew or drive or acquire any practical life skills because I was always the designated reader in the family.)

During the war, Shalvi’s family moved to a village in Buckinghamshire. When she was not performing in school plays, singing in the choir, or reading books from the lending library, she rode around the corn fields on a bicycle, learned to play tennis and cricket, and discovered British Romantic poetry: “One spring day, turning a bend, I found myself, unprepared, confronting a vast bank of daffodils. I had never before seen such an abundance of what appeared like wild flowers thronging an open space.” Years later, in Jerusalem, teaching Wordsworth’s poem about stumbling upon a field of daffodils, she was astonished to discover that her students had never heard of a daffodil. Five years ago, when substituting for my husband in the English department at Bar Ilan University, I taught this same poem and had the same experience. Like Shalvi, “only then was I made aware of the absence of this quintessentially English flower from the abundant flora of the holy land.”

Shalvi and a friend bribed a teacher with cigarettes to teach them Latin so that they could take the entry exams for Oxford and Cambridge. She was accepted to Newnham, then one of two women’s colleges at Cambridge, where she and her fellow students were expected to live cloistered lives: sex was considered “obscene, indecent, smutty,” and women had to sign out if they left the college after 8pm. Reading about Alice’s adventures in Cambridge, I am grateful that I attended this university over a half a century later, though I identified with many of her experiences: I too hung a photograph of the Kotel on my dorm room wall; I too suffered from an inadequate number of toilets (mine was across two courtyards, though fortunately my baths were not limited to a shallow five inches of water, the depth designated by a black line on the tub); I too attended Friday night dinners at the Jewish Society on Thompson’s Lane, where at the Sabbath meal (by my time, alas, this license had been revoked). As the only religious Jew in my English program, I had many experiences similar to Alice, who relates that she tried to explain the concept of simile to her classmates by citing the prayer in which the children of Israel’s relationship to God is compared to “clay in the hands of a potter”; she was dismayed to discover that few of her classmates had ever heard of this prayer. At Cambridge I also found that many of my frames of reference were foreign to my classmates, which rendered my experience there all the more lonely.

After Aliyah…

It was at Cambridge that Shalvi first became aware of the horrors of the Holocaust and the fate of her father’s brother’s family, all of whom were shot to death in their native Poland. “Worst of all and hardest to come to grips with, even today, was my growing awareness of a startling paradox: while the extermination of European Jewry was in progress, I was enjoying what were undoubtedly the happiest years of my adolescence, safe and secure amidst the natural beauties of rural England.” A Zionist from her early childhood, when she’d danced the hora around her family’s kitchen table, Shalvi resolved to move to Palestine: “I made the fateful decision to go there as a social worker, rehabilitate people like these youngsters, and assist them in becoming useful, committed citizens, fellow builders of a new Jewish state that, together, we would help bring into existence.” She went on her first visit to Palestine during Christmas vacation of 1947, less than a month after the U.N. vote on the partition plan but before the British withdrawal. The euphoria was evident, particularly in Tel Aviv, where “houses were shooting up, sparkling white in the bright Mediterranean sunshine that heightened the blue of the ocean with an intensity never seen in England. I’d not expected the sun to be so blinding, the sky so cerulean, the sea so calm.”

After studying social work at the London School of Economics (L.S.E.), Shalvi made aliyah, settling in Jerusalem in November 1949. She recalls a period when everyone walked around confused, unsure whether the street they were on was called Queen Melisanda or Heleni Ha-Malka. In neighborhoods like Talbiye, Katamon, and Baka—where I live now, with all modern conveniences— the streets had no names, the houses had had only plot numbers, and no one had telephones at home. In her first year in the country, she was seduced by her landlord who forced her to sleep with him when his pregnant wife was out of the house; “today,” she writes, “we’d call it rape.” Shalvi describes several men she dated as a young single woman in Jerusalem, though she never explains how she overcame the sense of unattractiveness that haunted her as a child: “My bust was too small, my hips too broad. Even had my mirror not reflected the reality… many wounding comments on my appearance… combined to instil in me both an overwhelming sense of my own inadequacy and a comparable need to compensate. Such compensation might be accomplished by academic achievement.” Surely her academic achievement was responsible for some of her confidence, but it is still hard to understand where she mustered the courage to pursue and then propose marriage to the handsome young American banker named Moshe whom she fell in love with when she first sighted him at a party for the Hebrew University. The couple set off to Paris on their honeymoon, where they bought baguettes and cheap plates and cutlery so that they could eat in their hotel room, since Moshe kept strictly kosher. “It was our first experience of keeping house together. We made abundant and blissful use of the big brass bed. We were inordinately happy. The week in Paris proved an auspicious beginning to over 60 years of compatibility and compassionate companionship.” Moshe took pride in Shalvi’s professional accomplishments and always encouraged her to excel, never feeling threatened by her achievements. He was, in every sense, just as feminist as she.

Shalvi became pregnant soon after their marriage, and she went on to have six children in 15 years: “My conception of a happy family was undoubtedly inspired by the numerous books I read that portrayed the adventures of siblings engaged in a series of fascinating activities… I envied these fictional families and perhaps unconsciously longed to replicate them in my own adulthood.” Her first pregnancy in 1951 was during a period of rationing, when pregnant women were allocated two fresh eggs a week, but she felt happy and healthy. On a visit to London she bought a book about natural childbirth and taught herself its precepts, shocking the doctors when she refused medication during labor: “It seems I was Israel’s pioneer of natural childbirth,” she muses. Her labor pangs began during an English department study session at her apartment, where members of the faculty were gathered to read Blake, and throughout her children’s early years, she and her husband remained intensely engaged in their respective professions.

Shalvi’s reflections on working motherhood are brave, candid, and—surely not just for me—deeply inspiring. She acknowledges that she was not present for her children nearly as much as they needed or wanted her to be, but she is proud of the people her children became: “I was not a source of the loving individual attention every child desires and needs. Frustrated, they sought other sources of attention and affection—friends, lovers, and eventually spouses. Today my children reproach me for my neglect but I take a certain degree of (cold) comfort in the fact that they’ve learnt from their own negative experience and that they, in contrast to me, are not only model parents but equally dedicated grandparents.” How refreshing that Shalvi can write so openly about her inadequacies as a mother, while also appreciating decisions that leave us feeling most uneasy can prove surprisingly salutary.

In one of the more private and painful moments in this memoir, Shalvi reflects on an illegal abortion she underwent in 1950s Jerusalem. She became pregnant while her older children had mumps, and her doctor informed her she had to terminate the pregnancy because infection with mumps could result in brain damage in the embryo. Shalvi reluctantly and ambivalently consented. She continues to be plagued by what she underwent in the back room of the doctor’s house: “I never told Moshe about the abortion. I fact, I told nobody. I have never spoken of it. Yet similarly, I have never forgotten it. Though I gave birth with my customary ease to three additional blessedly healthy, carefully planned, children, the thought of that unborn child still plagues me. Was it a girl or a boy? Fair-haired like Micha or dark like Ditza? As placid as Hephziba or wild, like Benzi? And would it indeed have been in some way abnormal, or might it, despite our fears, have proved no less healthy than its siblings? The questions can never be answered; the regret and guilt never fully assuaged.” Decades later Shalvi would go on to fight for increased awareness of women’s medical and psychological needs.

Gender Inequality, First-Hand

Shalvi learned her compassion and her concern for others from her own life experiences. When she birthed her first son, her roommate in the maternity ward of the Anglican school where Hadassah Hospital was then housed was a gaunt Kurdish woman who had just given birth to her seventh child, and had no visitors. The woman lay there miserable as all the members of the English department took their turns visiting and congratulating Alice on the birth of her firstborn: “I learned a great deal through this pathetic woman and her experience, of the overriding importance in some cultures of bearing sons, of the lowly status of females…of the contempt in which new immigrants from the Arab countries were held by the European veterans.” Shalvi went on to become instrumental in founding a “Women’s Kitchen” in a poor neighborhood in Katamon, a clubhouse for women immigrants from Arab lands.

Though she had made aliyah with a degree in social work, Shalvi was unable to find work in her field. Instead she landed a job teaching in the English department at Hebrew University; among her students were the young Yehuda Amichai, Dan Pagis, and Dahlia Ravikovitch, who became some of Israel’s most famous and celebrated poets. Nearly two decades later, when her youngest child was a toddler, she accepted an offer to found the English Department at Ben Gurion University. Four years later, the position of university dean became vacant. “Few of the men (needless to say they were all men) whose names were mentioned [as candidates] had what I considered the necessary qualifications.” And so Shalvi submitted her candidacy. Here, as throughout this memoir, Shalvi does not come across as arrogant or brash. On the contrary, she had a realistic sense of her own abilities and a supportive husband always at her back, and she was undaunted by the possibility of failure. “But you’re a woman!” she was told by the humanities dean. “You should be ashamed of yourself,” said the incumbent she hoped to replace. She was accused of “blatant lobbying” and “shameless self-promotion,” and she did not get the job. But for Shalvi, each failure, like each success, was a learning opportunity. “My humiliating experience led to a profound change in my perception of gender equality in Israel.”

Shalvi went on to devote herself tirelessly to advancing the status of women in all sectors of Israeli society throughout the 1980s and 1990s. She served on the Namir Commission to propose legislation and administrative changes designed to improve the social, economic, and political status of women. She worked with religious feminists to campaign on behalf of agunot, women whose husbands were missing, and mesuravot get, women refused divorce. She was instrumental in founding the Israel Women’s Network, a non-partisan organization to advance women’s status. She organized an international conference of women writers in 1986 to raise the self-esteem of Israeli women authors, hosting such luminaries as Grace Paley and Marilyn French. She persuaded the head of television at the Israel Broadcasting Authority to begin designing programs for women, of which there were none. She spoke on panels with Palestinian women, searching for common ground. She was involved in a six-month in-depth investigation of human trafficking and forced prostitution. She helped raise awareness about women’s health issues, founding an information hotline that referred women to sensitive and sympathetic doctors. Just recently, when I called the national hotline of my health clinic and listened to the menu of dialing option, I was told for the first time that I could press “5” if I wanted to speak to a doctor or nurse about pregnancy or childbirth; I have no doubt that Alice Shalvi is responsible, albeit indirectly, for this development.

Educational Excellence for Religious Girls

And yet in spite of all her work on the national level, in Jerusalem Shalvi is perhaps best known for her tenure as principal of Pelech, a high school founded in the 1960s for ultra-Orthodox girls. From its earliest days, Talmud was part of the compulsory curriculum at Pelech; a rarity for girls’ schools at the time. (The name of the school means spindle, and is spoken derogatorily by a misogynist sage in the Talmud who contends that “Women’s wisdom is solely in the spindle.”) Shalvi first became involved in Pelech as a parent—her eldest daughter Ditza, who was unhappy in her Orthodox high school, asked her parents to transfer to the Pelech High School for Haredi Girls, as it was then known. Uneasy with the idea of sending her daughter to such a religious school, Alice climbed up Mount Zion—where the school was then housed—to check it out. She engaged one of the students in conversation, and discovered that this ultra-Orthodox girl was working on a paper on Christian symbols in the novels of Graham Green. “Christian? Graham Green? At a haredi school? This openness was beyond belief. After that I had no objections to Ditza transferring to Pelech.”

In 1974, when Ditza was still enrolled, the founders of the school announced their intention to close it down—they were uncomfortable with the “infiltration” of modern Orthodox families. One day shortly thereafter, during a visit from the Ministry of Education, the principal was asked whom the ministry should be in future contact with on matters regarding the school. Without a moment’s pause, the principal told him to be in touch with Professor Shalvi—and thus to her total surprise, Shalvi became the school’s new principal. Though the school was already catering to a more enlightened demographic, Shalvi found that her religious progressivism was often at odds with the school’s ethos; in her new role, she had to put away her elegant pantsuits and instead wear long skirts, though she was never able to bring herself to cover her hair, as many traditional Orthodox women do. When she tried to advocate for replicating the American bat mitzvah program she had witnessed on a recent trip, one of the male Jewish studies teachers caustically replied, “In an orchestra, when the violinist plays the notes composed for the violin and the trumpeter plays the notes composed for the trumpets, there is harmony. But when the violins play the trumpets’ notes and the trumpets play the notes of the violinists there is discord.” Chastened, Shalvi writes that she “learned never again to express my heretical views on the inferior status of women within the confines of Pelech.”

Even so, Shalvi continued to push the envelope in her role as principal—she hired an American woman with an expertise in Talmud to teach a course on women and Jewish law, and she brought in a commanding officer from the Israel Defense Forces to speak to her students about women’s service in the military. Ultimately, her heresy became too much for the school officials to bear, and she felt she had no choice but to resign so that the school would not lose its accreditation. Still, Shalvi remains inordinately proud of “my girls,” as she refers to her Pelech graduates, one of whom is now her own rabbi. “Surveying how feminism has affected Israeli society, one is compelled to admit that the greatest revolution has occurred in Modern Orthodoxy,” she contends. “Not only have the women themselves ‘come a long way’; they have carried their communities in their wake.”

Shalvi, who was the subject of Paula Weiman-Kelman’s documentary “Rites of Passage,” which aired recently on ABC, was tireless and tenacious in her professional and public roles. In 1990, when she was settling down for what she thought would be a quiet retirement, she was asked to head the Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies, which offered rabbinical training and advanced degrees in Jewish studies. Shalvi agreed and became rector and then president, a decision she later regretted: “The double burden was too heavy for one person to bear, and as I soon learned, I was totally ignorant as to the complexities of the Conservative movement in the U.S.” Even so, she acknowledges that she has “nothing but happy memories” of her days at Schechter, where she founded Nashim, an academic journal of Jewish feminist studies, and she helped create the Center for Women in Jewish Law.

Reading this memoir, I was struck by the enormous debt of gratitude that I, as a woman in Jerusalem, owe to Shalvi’s trailblazing. When Shalvi pushed for a bat mitzvah program at Pelech, such an idea was unheard of; there is no question that my daughters and their contemporaries will have bat mitzvah ceremonies. When I was pregnant, I had my pick of Lamaze classes to attend (though it was still difficult, in the early 2000s, to find a woman obstetrician/gynecologist). When I wanted to study Talmud on a high level, there was a host of institutions to choose from—some for women only, and some co-educational. And when I wrote a book about my experiences studying Talmud as a woman, the opening chapter was first published in Nashim, the journal Shalvi founded.

Feminism among religious women in Jerusalem is a funny thing; just recently, I offered a copy of Lilith magazine to a religiously observant friend my age who swims with me at the pool in the mornings after dropping off her children at school. “A feminist magazine?” she looked at me quizzically. “Sorry, that’s not for me. I’m no feminist,” she said, before heading out to teach history at the university. I wanted to call after her, “You’re not a feminist? How did you get to where you are, if not for the feminists? Why do you think you have childcare for your toddler? Why are you able to work as a mother? How did you get your maternity leave? What kind of historian are you?” But I knew my protests would fall on deaf ears. Her response is a reminder that we still have a long way to go. Alice Shalvi, having completed the memoir she began two decades ago, has taught herself to meditate and seems finally to have found tranquility: “No words are needed. No words suffice. Just as two lovers sit side by side in silence, each absorbing each other’s presence, so I sit absorbing and at the same time surrendering myself to the Divine Spirit.” There is more work to be done, but the mantle has been passed to my generation, and to my children. We are so fortunate to have Shalvi as our model, our mentor, our guiding light.

Ilana Kurshan’s own memoir, If All the Seas Were Ink, won the 2018 Sami Rohr Prize in Jewish Literature.

- No Comments

July 15, 2014 by admin

Behaviors from Generation to Generation

Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek famously criticized the way fat-free chocolate and decaf coffee have allowed us to rid ourselves of our guilt in today’s consumerist culture. Israeli author Orly Castel-Bloom extends this dystopian vision in her new novel Textile (The Feminist Press, $18.95; translation by Dalya Bilu), where housing developments are built with no ecosystem, homes are established in brand-new apartments with no past, family members try to forget their ties to each other, and even the body undoes the effects of time.

Castel-Bloom weaves together a multivalent and sprawling text, set mostly in a lavish but hygienic Tel Aviv suburb and the isolation of upstate New York. The narrative focuses on a wealthy suburban family of four, who revolve around each other without real intimacy or responsibility.

At the heart is Mandy, Amanda Gruber, a judgmental mother figure absorbed in her own efforts to look younger and anesthetize herself while her son serves as a sniper in the Israeli army. Meanwhile, her genius husband, a somewhat famous scientist in Israel, is absorbed in efforts to invent a special suit to protect the body from terrorism. The outlier, and inheritor of the family pajama factory, is young Lirit, who just broke up with her boyfriend and is beginning to fill her mother’s shoes.

With a keen eye for class and gender politics, Textile moves from one character to another and still feels like a quick read. The author often takes us back three generations to trace the way languages and behaviors get passed down l’dor v’dor, from generation to generation. The text itself is multilingual, with bits of French and even Yiddish thrown in, and always in transition, reflective of the “third millennium” of history and critical of it. Everyone is an exile in some sense, trying on new tongues and wardrobes, trying to adapt to a new environment.

Not only is the book international but it also feels slightly futuristic, in the way that the lifestyles of the elite always seem some- how at the cutting edge of civilization and closer to its end. The only control group in the experiment is Mandy’s inherited business, the Nighty-Night pajama factory, which serves the ultra-Orthodox community and stays unchanged, according to her mother’s dying wish.

Though the opening inscription from Leviticus warns us of the law of Shatnez, not to wear a garment of cloth made of two kinds of material, Textile explores what happens when worlds are forced to collide, how we try to protect ourselves and our bodies from life.

“History is a load. A burden,” an Israeli-expat masseuse tells the famous Israeli scientist on his first night in Ithaca, New York. And yet, “It’s no good being the first in a certain place. It gives rise to anxiety,” the scientist declares later in the middle of a nervous breakdown.

Caught in contradiction and paradox, dissatisfied and desperate for happiness, and painfully incapable of communicating with each other, these characters shop or work or read or get plastic surgery instead. Underneath it are relentless pangs of guilt and shame and past trauma, triggered by layers of the very history and relationships they can’t bear.

Though Castel-Bloom, author also of Human Parts and Dolly City, has something of a reputation in Israel for daring and macabre themes, this book is both readable and relatable, a testament too to Bilu’s seamless translation. Textile is a sharp and engaging study of individual psychologies in an age of anxiety and consumerism, and Castel-Bloom is a masterful storyteller for these interesting times.

- No Comments

July 15, 2014 by admin

From Russia, with Narrative

I read Panic in a Suitcase, the debut novel by Yelena Akhtiorskaya, by the ocean. At Brighton Beach, in fact—the fertile backdrop for this chaotic family saga. Reading the story on the shores of the Atlantic, it was easy to imagine the sundry oddball siblings stalking across the streets and into the bodegas and bakeries of Brooklyn’s “little Odessa by the sea.”

The remarkable corporeality of this vision emerges thanks to the surprising and vivid detail in Akhtiorskaya’s writing. In this novel of hectic depths, a Russian Jewish family of dissatisfied misfits emigrates from Ukraine to Brooklyn. The characters are characters indeed, trying to make a home for themselves on Coney Island Avenue, “a street where cars had many lanes but still bunched together and tiny people on the tiny strips of sidewalk seemed to be crossing a desert.“

In the Nasmertov family, every generation is unsettled in its own way. There’s the linchpin, the distracted Pasha—a spacey poet of indeterminate success who can’t decide whether to remain in Ukraine or finally join his family in Brooklyn. His sister Marina, who is fired from her job cleaning houses when she gives pepperoni pizza to the son of her Orthodox employers. Pasha’s father (who had no temper to lose) and mother (“Prisoners in labor camps hadn’t exerted themselves at an equivalent level of intensity for such hopeless durations”). And his niece Frida —poor Frida: “Impressive applied to Frida meant that she wear a dress and sit at the table. No one expected smiles, precocious conversation, grace.” The Nasmertovs are never quite at home in Russian-speaking Brooklyn, yet are far removed from their family and friends in Ukraine, and perhaps farthest of all from the Manhattan right above them.

In Lena Finkle’s Magic Barrel, a gorgeous graphic novel by the celebrated artist and author Anya Ulinich, the path from Russia to New York (and back, and forth) fades a bit more into the background of the winding story. Here we have one central protagonist —a warm, smart, wounded woman who emerges from years of cold or abusive relationships with two children and a lifetime’s worth of sexual confusion.

She embarks on a quest to find love (or is that sexual fulfillment? intimacy? stability?) while juggling single parenthood and a precarious yet successful enough career as a novelist. “I became a tourist in the country of men,” she writes, “or at least in the New York metropolitan area of men. I was like people who, when they felt like a road trip, shut their eyes, pointed to a random spot on a map, and drove…”

Lena’s insecurities and narcissism are deeply sympathetic. She berates herself—“What is it with you immigrants? Why are you so afraid of yourselves? … For all your proclaimed affection for Dostoevsky, you’re an excellent immigrant child, Finkle, a.k.a. a smart drone!” Lena traces her life in relationships, marks time by counting men, and avoids her work by browsing on OkCupid.

The imperfect, floundering characters in these two novels are deeply relatable. They leave you with the distinct impression that each person, each family, is no more or less unhinged and absurd than any other. In the midst of these distinctive migrations, it is the emotional familiarity of these characters that makes each one so compelling.

- No Comments

July 15, 2014 by admin

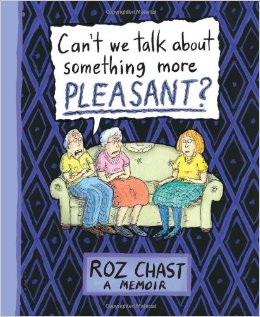

Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?

Roz Chast’s new memoir.

Calling Roz Chast’s new book a tearjerker would be silly.

The graphic memoir will evoke noises from you that a normal crying person would not make: low moans, ragged breathing.

It took me a second to realize that the Sounds of Grief were coming out of me—I was the person enjoying this fantastically quick-witted, sweet, insanely and perceptively funny new book by her favorite cartoonist. But they were.

Roz Chast’s cartoons have been an (the?) off-the-wall mainstay of The New Yorker for decades. They feature nervously drawn, quavering people, stupidly smiling horses, and inanimate objects with delightful expressions on their faces. They are often set in living rooms and sometimes include a lumpy couch, an armchair, wallpaper, and a really stupid painting of boats on the wall.

On the cover of this book, the author sits with her two aged parents on a lumpy couch that is familiar to us from her cartoons. The argyle-patterned wallpaper is of a deathly hue: dark purple on black. All three of them look deeply uncomfortable.

The title, “Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?” is what Chast’s parents would say to her whenever she tried to talk to them about “end of life plans.”

George and Elizabeth Chast were born in 1912, 10 days apart. They grew up two blocks from each other in East Harlem, and were in the same fifth grade class. Elizabeth had been an assistant principal, domineering and “built like a peasant,” who referred to her terrible temper, chillariously, as “a blast from Chast.” George was a high school teacher. He was slight, kind, an explorer of word origins, a careful chewer of food, and suspiciously inept when it came to using toasters and other gadgets.

He loved bananas; she hated bananas. They argued often about fruit and other things. But they referred to each other—this was both sweet and a little horrifying—as soul mates. They did everything together.

In one of the first pages in the book we read the story of how, one day in 1940, a light bulb burned out in their apartment. George had a phobia of light bulbs and also of step stools, so Elizabeth stood on the stool and replaced the bulb. She was six and a half months pregnant. Soon after that, the pregnancy developed terrible complications, and she gave birth, prematurely, to a “perfectly formed, but blue” baby who died one day after it was born. The complications had nothing to do with the changing of the light bulb, but still the connection between baby death and changing light bulbs became an unspoken part of family lore. The story does not come up again, but it sets the tone of the book, which is a tragedy told in anecdotes.

Baby Roz came along 14 years after that first baby. An only child, she always felt like an intruder in her parents’ “tight little unit.” In the family photographs included in this book, she is not smiling.

In 2001, after avoiding Brooklyn for 10 years, she has a sudden, intense urge to visit her parents, who are nearing 90, in their old home.

The first thing she notices is that everything in the apartment is coated in grime. Her parents are frailer than she thought, and less able to manage. Uneasily, she wonders: what next.

Two days later, the twin towers fall.

Her parents quickly go back to arguing about bananas. But their decline is underway.

In a series of keen, lucid observations of tiny, insane details, Chast describes her father’s senile dementia and her mother’s harrowing digestive ailments, the weirdly cheerful “Place” she convinces them to go live in (she hangs decorative corn cobs on their door, because “when in Rome”), their fear and crankiness, the responsibilities that land on her, the chilling truths about “stuff ” known only to people who have had to clean out their parents’ houses. This is the story of George and Elizabeth’s drawn-out, confusing, stressful, sad, expensive deaths.

The narrative is modular. Each page could easily stand on its own as a full-page cartoon —the type Chast publishes, when we are lucky, in The New Yorker. Each page, on its own, is completely funny— funnier than sad.

How does Chast string together the “minutiae” of cartoons and anecdotes and old photographs? Did she put a lot of work into switching from “cartoonist”’ to “graphic novelist”? Did she change her voice to accommodate the seriousness of the subject matter?

If she did wrench this story out of herself—if she did strain herself to make a million tiny and difficult adjustments to her craft—we can’t tell. The story flows so easily. The large-scale tragedy grows out of the surprising and human details as naturally as it does in Shakespeare. When you read Romeo and Juliet, you don’t say: wow, how does he focus simultaneously on the big and the small, the sad and the funny? Somehow, deceptively, while you are reading, everything is obvious to you: the story could not have been told any other way, and it is the only story that could have been told. Roz Chast makes telling the sad truth in funny pictures seem effortless—makes it seem obvious.

- No Comments

July 15, 2014 by admin

Much More Than An Israeli “Private Benjamin”

Zero Motivation film

“Zero Motivation” is a new and delightfully poignant Israeli film that zings myths of women’s equal participation in the Israeli army, with frank humor and staple guns to battle the military’s bureaucracy and sexism.

Inspired by her own experiences with other women relegated to boring assignments in administrative offices for their mandatory two-year army service, writer/director Talya Lavie’s debut premiered at the 2014 Tribeca Film Festival in New York City, where it garnered two awards. “We believe a new, powerful, voice has emerged,” crowed the jury for the competitive Best Narrative Feature award. The jury for the second annual Nora Ephron Prize for a female director or screenwriter, which included Delia Ephron, offered similar acclaim, stating that “Zero Motivation” was “definitely the most hilarious film we saw at the festival…the winning film is a fresh, original, and heartfelt comedy.” But this isn’t just an Israeli version of “Private Benjamin”; this film is far more darkly pointed and complex.

The film follows one year in the life of soldier-secretaries in the human resources office at a desert base in the south of Israel in 2004, a year marked by rapid changes in technology and gender relations. The narrative unfolds in three chapters. The first expands on Lavie’s 2005 20-minute film-school thesis, “The Substitute” (available online with an English transcript), focusing on the naïve schemes of Daffi (Nelly Tagar), who hails from a northern town, to find a replacement so she can transfer to Tel Aviv. Part 2, “The Virgin,” focuses on Daffi’s best friend, Zohar (Dana Ivgy, a renowned young film star), for whom “anything is better than the kibbutz”—even a forlorn desert outpost. As the titular virgin, Zohar is enticed by the unfamiliar presence of men she wasn’t raised with, and begins to take sexual risks. When she is briefly liberated from paperwork, her first assignment on guard duty becomes a vengefully comedic moment that involves humiliating male nudity at the point of a gun. By Part 3 Daffi has become “The Officer,” to the frustration of their ambitious, perpetually thwarted supervisor Rama (Shani Klein), who wants to make her pioneer soldier mother proud, despite the rebellious women serving under her and the condescending men over her.

Lavie deftly balances comedy with deadly serious issues. She sensitively portrays an array of women from diverse social strata, including an immigrant from Russia and one from Ethiopia. Focusing the lens tightly on young female soldiers, she reveals the ways in which these women are at once fully developed adults and game-playing teenagers. Mean girl cliques, eating disorders, text-messaging miscommunications, boyfriend troubles and suicide loom larger than any external enemy. Opening first in Israel, Canada, and Australia, Zeitgeist Films will put this must-see for Jewish feminists in theaters across the U.S. later this year. Don’t miss it.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...