Tag : prayer

December 16, 2020 by admin

This Hanukkah, Illuminating the Power of Feminists

Four years ago, I sat in a communal Shavuot learning program. I recall thinking to myself, what is the Torah that the Jewish people need right now? The answer became crystal clear: it is feminism.

The next year, I decided to experiment and organize an event called Feminism All Night. The vision was inspired by the Jewish holiday of Shavuot and brought feminist thinkers together to teach and learn communally about feminism. The success was overwhelming, with over 100+ attendees and over 12 sessions that had us staying until 4 AM.

Since then, I have been cultivating this project by designing immersive feminist communal learning experiences centered on Jewish holidays. We hosted Feminism All Day for the holiday of Sukkot and expanded our events from Oakland to various cities, including Boston and Tel Aviv. Our community has grown to over 1500 people!

This year we decided to bring our vision of feminist Jewish learning to Chanukah. On the 7th Night of Chanukah on Rosh Chodesh Tevet is the traditional celebration of Chag haBanot (Eid al-Banat in Arabic), a North African Jewish Festival of the Daughters. The holiday elevates women’s power–the strength, wisdom and resilience of women throughout the ages. Women, young and elderly, would gather for a celebration together to delight in sweets, sing prayers, dance, and give gifts to each other, particularly gold coins and jewelry.

The holiday is associated with legendary and midrashic traditions or literary and historical traditions, about bold, wise, courageous and determined women who saved their people with their resourcefulness, wisdom, courageous hearts and heroism, and changed historical circumstances in antiquity.

Chag haBanot elevates the heroism and resourcefulness of brave, bold and wise women, such as Queen Esther, Judith daughter of Merari, or Hannah [sometimes Miriam], daughter of Matityahu. In times of danger to their people, they gathered courage, devotion, strength and resourcefulness, and acted in extraordinary ways that are recorded in the chronicles and told by the women on The Festival of the Daughters.

Feminism All Night is committed to creating space for feminist learning and particularly uplifting Mizrahi traditions in the Jewish world. Our programming has centered Mizrahi feminist educators from the beginning. We love celebrating the sacred traditions and teachings of Mizrahi communities and bringing them forth to the wider community.

This year, on December 16th and 17th, we are hosting Illumination: A Chanukah Celebration of Devotional Arts and Embodied Prayer. Illumination is a collaboration between Hadar Cohen and Taya Mâ Shere. It is a partnership with Kohenet Hebrew Priestess Institute and is supported by Moishe House. The festival includes prayer, workshops and celebration. In honor of this celebration, we are featuring North African Jewish feminists–artists, teachers and spiritual leaders–on our Facebook and Instagram pages. Our programs are open to people of all genders and faiths and we invite you to join us–register here!

Some of our featured feminists include:

Sivan Tahel, a Moroccan activist and leader who was a lead organizer of Feminism All Night in Tel Aviv, January 2020, centered on Mizrahi Identity.

“Feminism is the mother of all struggles and everything connects to it. Feminism for me is solidarity, support networks of women, empowerment that is expressed in action, advancing other women and caring for their well-being, emotionally and financially. It is the ability to hear and listen to various strands of feminism, while respecting and embracing the diversity within the group of women. Feminism is the expansion of the feminist struggle with reference to power structures, ethnicity and status.”

Nellie Alimi, a Tunisian and Algerian French artist who is working to preserve the North African rituals and traditions that she grew up with. Her family celebrated Eid Al Banat, and she will be sharing more about her familial lineage celebration at our Artistic Showcase.

“Feminism for me, is about elevating other women, showing a different type of leadership, embracing our own selves, not trying to fit into the white male model, speaking out truth, educating the world about strong women leaders and their challenges.”

Daniela Labi, a Libyan feminist artist and community organizer. Daniela was one of the lead organizers for Feminism All Day 2019 in the Bay Area.

“To me, feminism means celebrating the true feminine power that lies within all of us. Feminism is the act of re-calibrating society so that we honor this power, lift it up, and use it to return to true alignment with g!d, the earth, and the universe. My mother was born and raised in Tripoli, Libya. She fled with her family in 1967, during the Six Day War, just months before she would’ve entered her last year of high school. For years, my ancestors lived in the deserts of Libya, and I feel the divine responsibility to capture their stories so that they are not lost to eurocentrism and whiteness.”

Hadar Cohen is a multimedia artist, educator and healer. She is the founder of Feminism All Night. To learn more about her work visit hadarcohen.me.

- No Comments

January 16, 2020 by admin

Prayer, Illuminated

I’ve never been a morning person, but not long after moving into an apartment with large windows facing the rising sun, my life changed. I would instinctively wake up to watch the colors gradually brightening from midnight blue to the dawn’s splashes of pinks and purples across the horizon. As the metallic magenta ball rose in the sky, I would sing Modeh Ani, the morning prayer of thanks. As my living room became awash with golden light, I would pray with more fervor than ever before, knowing my day is a gift, one I took for granted a little less today.

In the first tractate of the Talmud, the volume of Berachot, “Blessings,” that debates the hows, whys, and whens of prayer, the Rabbis discuss the where of prayer, instructing people that no matter where they are, they are to “direct their heart” towards the Holy of Holies in the Temple in Jerusalem. Even when physically incapable of facing that direction in body, the “orientation of the heart,” kivun libo, is paramount. I considered this when reading the introduction by Marcia Falk to her gorgeous collection of illuminated poems and blessings, Inner East (Oak & Acorn Press, available at https://www.marciafalk.com/innereast.html). In her introduction, Falk describes how her lifelong dream of pairing her visual art with her already popular poetry and prayer collections (The Book of Blessings, 1996, previously reviewed in Lilith, was endorsed when she recalled the time-honored tradition of placing a Mizrach sign (“East” in Hebrew) on the east wall of synagogues in Western countries, to indicate the direction of Jerusalem. A heart-orientation reminder, if you will.

It reminded me of my morning sunrises, and how a visual reminder of the awe-inspiring nature of the Divine enhances my prayers with every cue. In the introduction, Falk notes that the words zericha, “sunrise,” and mizrach, “east,” share root letters. The mizrach pnimi, the “inner east,” is the place where the self rises, from where it radiates.

Although the book is technically divided into two sections—Poems “The Earth and Its Fullness” (a direct quotation from Psalms) and Blessings “Of World and Time,”—the truth is every poem reads like a blessing or prayer, and every blessing is a poem.

“We Know Her,” a resounding prayer to the “her” that is Spirit, the Divine, God, or Goddess, reads like a mystic’s spiritual wanderings, encountering the Divine in every step in nature.

We breathe her as she lifts to the sky

the scents of the newly furrowed field,

and feel her touching our forehead

in our fevered dreams.

Poems of earth, clouds, wind and community meet prayers that echo the traditional liturgy of old, with language that is shaped just as beautifully as the accompanying visual landscapes.

It’s this beauty of language and encapsulation of meaning that has made Falk’s original Book of Blessings a reference point for me in those sacred morning moments, during uninspired evenings, or before preparing to lead a prayer service. (Two years ago, on its re-release, I listened to Falk at Romemu in New York City laugh and breezily discuss her prayer practice, God as feminine, and the importance of keeping services short (shock! horror!). That earlier book’s evolution into Inner East blossomed from a decisive turn—after the original Book of Blessings publication, coinciding with the author’s fiftieth birthday—to return to visual art, pairing her two lifelong passions of writing and painting.

The morning blessing, accompanying a glorious sunrise painting and Hebrew words closely aligned to a traditional liturgical prayer, Nishmat, “the breath,” is simple, divine, every word carefully balanced.

The breath of my life

will bless,

the cells of my being

sing,

in gratitude,

reawakening.

For those already in love with Falk’s artistry through carefully chosen words, in both Hebrew and English, that build on and expand the framework of traditional prayer with inclusive, egalitarian language, vivid descriptions, and evocative descriptions of nature, it is a treat to witness these delicious phrases alongside gorgeously crafted paintings, reproduced in full color in a prayerbook that merits upgrading to coffee table status. Transforming the art of prayer into vivid images of color is a reminder that no matter where we are, all it takes is a small cue for us to guide ourselves to our own Mizrach, to our Inner East.

RISHE GRONER loves to pray. Her writing can be found on www.thegene-sis.com and on Instagram @thegenesisters.

- No Comments

November 4, 2019 by admin

Graphic Medicine•

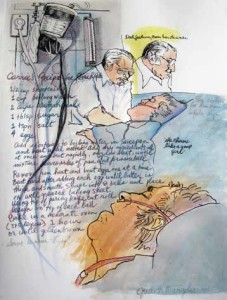

The endpapers of this small book list prayers: “Prayer for the ransoming of time; Prayer to be cared for; Prayer to accept care; Prayer to accept not being in control; Prayer for making deals; Prayer for a reunion; Prayer for help in the struggle with faith; Prayer on beginning whatever will happen next; Prayer to create prayer when I never prayed before…”  During the year after her mother’s death, artist and essayist Judith Cohen Margolis rented a studio where she painted from sketches and photos she’d taken during the course of her mother’s long illness. This activity became her way of mourning, of “saying Kaddish.” Eventually, ten years later, she created a small meditative book for herself. She called it “Life Support: Invitation to Prayer,” now the title of a new volume intended to inspire or comfort others on the journey of attending loved ones’ dying. From Pennsylvania State University Press.

During the year after her mother’s death, artist and essayist Judith Cohen Margolis rented a studio where she painted from sketches and photos she’d taken during the course of her mother’s long illness. This activity became her way of mourning, of “saying Kaddish.” Eventually, ten years later, she created a small meditative book for herself. She called it “Life Support: Invitation to Prayer,” now the title of a new volume intended to inspire or comfort others on the journey of attending loved ones’ dying. From Pennsylvania State University Press.

- No Comments

July 15, 2014 by admin

A Woman’s Tashlich

It’s been 18 years since Marcia Falk, renowned Jewish feminist scholar and poet, brought us her groundbreaking The Book of Blessings: New Jewish Prayers for Daily Life, the Sabbath, and the New Moon Festival, a prayer book that not only uncoupled liturgy from patriarchal themes and imagery, but that gave women —and continues to give women —contemplative, gender-corrective ways to connect to the sacred.

It’s been 18 years since Marcia Falk, renowned Jewish feminist scholar and poet, brought us her groundbreaking The Book of Blessings: New Jewish Prayers for Daily Life, the Sabbath, and the New Moon Festival, a prayer book that not only uncoupled liturgy from patriarchal themes and imagery, but that gave women —and continues to give women —contemplative, gender-corrective ways to connect to the sacred.

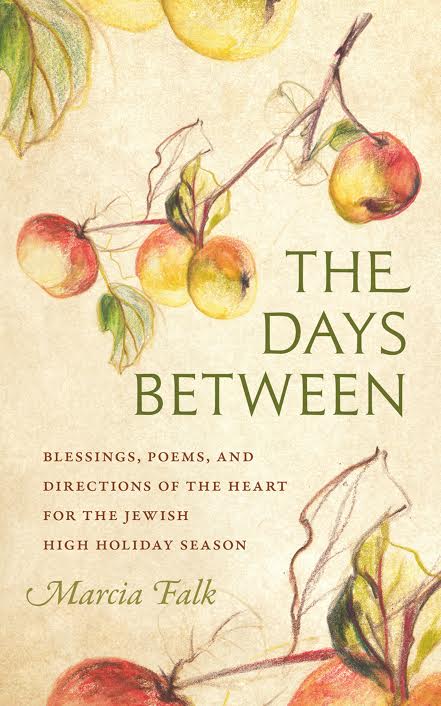

In Falk’s new book, The Days Between: Blessings, Poems, and Directions of the Heart for the Jewish High Holiday Season (Brandeis University Press), she takes us further down the same spiritual path, reminding us that it is good to experience “the turning of the Jewish year” in nature, and that it is holy to immerse ourselves mindfully in endings and beginnings, in solitude and in relationships. “What kind of life will we live in the time we have?,” Falk asks. “Where in our life will we find purpose and meaning?”

Falk underscores that the period between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur (Aseret Y’mey T’shuvah) is intended to be a continuous devotional span; “ten days of meeting oneself face-to-face, opening the heart to change.” The word “between” in the book’s title palpates one of women’s special strengths: connection. Alas, we humans cannot stop time —we can’t make our six-year-old stay six forever, or bring a beloved deceased person back to life —but we can strive to be “fully aware of our connectedness to everything in our world,” and in that way live ourselves into “wholeness, serenity, and fulfillment.”

I asked Marcia if she would take a walk with me, for tashlich, along a river’s edge, using five poems from The Days Between as guideposts. (Tashlich is the ceremony in which Jews throw crumbs into the water to symbolize casting away our sins. In The Days Between Falk calls her new ritual Nashlich, which is gender-inclusive, “we will cast,” rather than Tashlich, “You [God, masculine] will cast.”) In the pages that follow here, she does this, helping me journey spiritually through her translations of poems by the well-known Hebrew poets Zelda and Leah Goldberg, and by the less well-known Yiddish poet Malka Heifetz Tussman. We begin our walk with Falk’s own poem, which revisions Micah 7:19, the biblical verse that opens the traditional tashlich. As we recite and then discuss the poems, they become cast as a prayer cycle. (I have distilled our conversation.)

Each of the poems, says Falk, “uses the archetypal sym- bol of water as revelatory, transformative, and redemptive.” Each “explores time, change, and mortality in the context of intimate relationships; and in each, water is given a voice. Zelda’s sea sings, Goldberg’s river hums, Tussman’s creek babbles.”

Reader: Take a walk with us. Put some crumbs in your pocket for tashlich, and find a serene place alongside water…water that eddies or babbles, water that cascades or crashes, water that hardly ripples. Enter “the between,” give voice to a conversation with your life, move forward along the meridian of deepening t’shuvah.

Hey, you! Come along, too.

CASTING AWAY

We cast into the depths of the sea our sins, and failures, and regrets.

Reflections of our imperfect selves flow away.

What can we bear,

with what can we bear to part?

We upturn the darkness, bring what is buried to light.

What hurts still lodge,

what wounds have yet to heal?

We empty our hands,

release the remnants of shame,

let go fear and despair

that have dug their home in us.

Open hands, opening heart —

The year flows out, the year flows in.

—Marcia Falk

MARCIA FALK: The High Holiday language is full of power and terror, and the verse from Micah that we recite for the traditional tashlich ritual is vivid, almost violent, asking God to hurl all our sins into the depths of the sea. I have a different image of the new year, of life and change. A wave comes to shore and then pulls back, there’s ebb and flow. Is it only our “sins” that we need to let go into the sea?

SUSAN SCHNUR: In the third stanza of Casting Away, you ask, “What can we bear?” Help me understand this.

FALK: For example, can I bear to live with the knowledge that I was mean to my child? Can I accept the “mean” parts of myself? Can I forgive myself?

SCHNUR: And then the poem asks, “With what can we bear to part?”

FALK: Yes. What can we let go of? I’m in the process of clearing out 20 years of clutter from my house, and I’m overwhelmed. I have to look at each thing: Can I part with this? Can I part with that? It can be hard to let go, to stop looking backwards. This is the time of year when we want to be able to walk into the new, but the old holds us hostage. Can we “release the remnants of shame,” let go the despair that has “dug [its] home in us”? The holiday is about perfecting ourselves —but not everything can be changed. Can we accept ourselves?

SCHNUR: Okay, here’s what I want to personally ponder in the palimpsest of this poem: This year, can I live less reactively in life’s ebb and flow?

FACING THE SEA

When I set free

the golden fish,

the sea laughed

and held me close

to his open heart,

to his streaming heart.

Then we sang together,

he and I:

My soul will not die.

Can decay rule a living stream?

So he sang

of his clamoring soul

and I sang

of my soul in pain.

—Zelda

FALK: Now we come to “Facing the Sea,” in which the speaker finds this Other —the sea —that is so unlike her. The speaker is quietly suffering, but the sea is noisy, laughing, bubbling over. Nature is completely alive, always alive —this noisy sea, embrac- ing us, holding us close.

SCHNUR: “My soul will not die”—they sing together about their shared immortality, that dying never conquers life. But the speaker remains so alone. The “Other” can only comfort us up to a point. Is that right?

FALK: The speaker lets something go —“the golden fish,” what- ever that is —and she is embraced. Then the speaker and the sea sing together, but their voices are very different. This poem, for me, is about being in pain and trying to find comfort.

SCHNUR: Here’s what I think I need to think about here: Can I learn to accept someone else’s imperfect love? Can I sing with the universe?

THE BLADE OF GRASS SINGS TO THE RIVER

Even for the little ones like me,

one among the throng,

for the children of poverty

on disappointment’s shore,

the river hums its song,

lovingly hums its song.

The sun’s soft caress

touches it now and then.

My image, too, is reflected

in waters that flow green,

and in the river’s depths

each one of us is deep.

My ever-deepening image

streaming away to the sea

is swallowed up, erased

on the edge of vanishing.

And with the river’s voice,

with the river’s psalm,

the speechless soul

will sing praises of the world.

—Leah Goldberg

FALK: This poem and the next are from a sequence by Leah Goldberg called “Poems of the River.” In the first poem here, a tiny blade of grass sings to the river. We all feel, at some time in our lives, that we’re “on disappointment’s shore,” that we are insig- nificant, “children of poverty”—a very touching phrase for me. But nature can comfort us —“the sun’s soft caress.” The river, in fact, takes our “images” —our faces, our selves —and deepens them.

When our mind quiets down, we get to sing “with the river’s voice, with the river’s psalm,” and we finally feel ourselves part of everything. Water here is wholeness, vitality, moving, streaming away to the sea.

So many of us experience ourselves as small—“even for the little ones like me” is such a poignant image. Why does the little blade of grass want to assure us that the river hums for us, too, lovingly? The blade of grass itself becomes our comforter.

SCHNUR: I love the rushing compassion of this poem. I want to say, “Yes, yes. Don’t leave without me!” This poem makes me want to think about the spiritual challenge of trust. Can I trust that everything will be okay?

THE TREE SINGS TO THE RIVER

He who carried off my golden autumn,

who with the leaf-fall swept my blood away,

he who will see my spring return

to him, at the turning of the year —

my brother the river, forever lost,

new each day, and changed, and the same,

my brother the stream, between his two banks

streaming like me, between autumn and spring.

For I am the bud and I am the fruit,

I am my future and I am my past,

I am the solitary tree trunk,

and you—my time and my song.

—Leah Goldberg

FALK: Ah! Here we find a less quiet voice, the self-possessed voice of the tree describing its relationship to the river. We don’t normally think of “blood” [in the second line] when we think of trees; we associate that with animal life, and when the animal is drained of blood it dies. The image is shocking, even suggestive of domination and submission: the river carries away the tree’s life-blood, yet the tree returns to the river again and again. Or, another way to look at it: perhaps the voice is defiant; it will not die, it will return, year after year.

There’s movement, a shifting of perspective. In the second stanza, the tree and the river are kin: the river streams, like the tree, between seasons. But in the last stanza the tree lets the river know that he, the tree, is solitary, whole in himself: “I am the bud and I am the fruit, I am my future and I am my past.”

Then, at the end, there’s a powerful reversal. The tree no longer addresses the river in the third person—as “he,” as “my brother”—but says, “you—my time and my song.” We aren’t solitary after all. There’s always “the other,” we exist in time, vis-à-vis the other. What is my voice if I’m just talking into the emptiness? I don’t have a voice unless I’m speaking to you.

SCHNUR: This poem breaks my heart. The tree is learning how to move from Martin Buber’s “I-It” relationship —separate, detached, full of defensive bravado—into an “I-Thou” relationship—of mutuality, of reciprocity, of touching interdependence. This challenge hits home for me: Can I learn to be more empathic and more yielding in my relationships?

from TODAY IS FOREVER

I stroll often in a nearby park —

old trees wildly overgrown,

bushes and flowers blooming all four seasons,

a creek babbling childishly over pebbles,

a small bridge with rough-hewn railings–

this is my little park.

It’s mild and gentle

in the breath-song of the park

and good to catch some gossip

from the flutterers and fliers.

Leaning on the railing of the bridge,

seeing myself in clear water,

I ask, Little stream,

will you tumble and flow here forever?

The creek babbles back, laughing,

Today is forever:

Forever is right now.

I smile, a sparkful of believing, a sighful of not-believing:

Today is forever.

Forever is right now…

—Malka Heifetz Tussman

FALK: This last poem is a little touch of mameloshn [Yiddish] in the middle of my book. Once again, water gives us its wisdom. The speaker talks to a stream, sweetly, as though to a child: “Little stream, tell me. Will you be here forever?” Human beings want to know! Are we going to live or die? What’s coming next?

And the creek laughs: Why are you asking such a question? This is what there is! “Today is forever.” The poor creek to have such a foolish disciple!

SCHNUR: Yes, how can we humans think about ourselves with- out thinking about the fact that we will die?

FALK: In every nature poem, there’s a dark thread. I like this poignancy; so much of Jewish liturgy doesn’t acknowledge it. I’m talking about sadness. There’s awe, fear, trembling, God is big, we’re small, all of that. The Kaddish: we exalt You, we enlarge Your name. How does that help one feel better? You’re sorrow- ing, you’re grieving, and what does the liturgy give you back? A big silence. Not much comfort. These poems by Jewish women offer us more.

SCHNUR: This poem asks the biggest question perhaps. Here go my last breadcrumbs into the water. How can we acknowledge life’s sadness? Can we do so and smile?

Sections in blue are excerpted from “The Days Between: Blessing, Poems, and Directions of the Heart for the Jewish High Holiday Season,” © 2014 by Marcia Lee Falk.

- No Comments

December 8, 2008 by admin

The Shekhinah Sh’ma: Six Little Words to Shake the World

Susan Schnur: Ariadne, so this Shekhinah Sh’ma popped into your mind full-blown?

Ariadne lieber: Yes. I was praying, and I often pray feeling half-alienated. Here’s the traditional Sh’ma: “Hear, O Israel: the Lord our God, the Lord is One. Blessed be His glorious kingdom forever and ever.” Ichhh…. The words “Lord,” “His,” “glorious kingdom” — I don’t relate to lords and kingdoms. Spiritually, this isn’t what I need to say. For goodness sake, it’s the 21st century.

Schnur: Your doctoral dissertation was on the motif of joy in biblical prophecies, and you’re a spiritual intuitive. This makes you an interesting pray-er. Can you walk us through these six little words?

Lieber: Well, the first two words are unchanged — “Sh’ma Yisrael” — but I certainly don’t think of translating them as “Hear, O Israel,” which is the traditional rendering. That has an administrative sound to me and feels patronizing and anti-me. “Listen, Israel” is much stronger, more open, it’s not somebody trying to tell you — trying to tell the one who’s praying — what to do. It’s a process; listening is deep. It’s active. “Listen” means “Stop for a moment. Become absorbed in this.” The pray-er will come up with something. “Listen” — I’m getting my own attention here.

Schnur: Paying attention is a spiritual act. It’s like that magnificent Denise Levertov poem about marriage. One partner says to the other, “You have my attention” — what an exquisite thing to say to the one you love. “You have my attention: which is a tenderness, beyond what I may say.” I’ve done wedding ceremonies where I adapt this poem into nuptial vows.

Lieber: “Listen, Israel” is also someone else talking to the ancient Israelites, myself among them. It’s the eternal me, the big me. It’s Everyjew. It’s Frankie’s “the we of me” from Member of the Wedding.

Schnur: And Walt Whitman’s “I contain multitudes….”

Lieber: Right. Embracing everything. “Sh’ma Yisrael” is an invitation: “Okay, I’m listening, I’m excited. What do you have to say?”

Schnur: Well, the next two words: “Ha-Shekhinah b’kirbainu” — that God’s presence or indwelling is in our inmost being, is among us.

Lieber: Yes. The Shekhinah is a female naming of God, it’s the term for divine immanence; that is, the God within us, circulating all around us, the God in everything. It’s not the God over us, it’s not that Lord God on a throne.

Schnur: The Shekhinah dwells with us.

Lieber: I don’t like the word “God.” It’s a dry word. It’s cold. It doesn’t do anything for me. It has a masculine sound in my ear. Gott. Sort of military. A choppy, cut sound. To be honest, it repels me. Shekhinah takes me further, to a different place. Shekhinah is a spirit, not an image. It’s a feeling of divinity all around you. A presence you can’t deny, an indwelling. In Chinese, it’s your Qi [pronounced “chee”]. And I like “the” Shekhinah — it’s an honorific that includes us.

Schnur: How are you with “the Lord our God” — “Adonai Elohainu” — in the original Sh’ma?

Lieber: It’s so distant. It’s out there. Where is this guy? Who cares? There’s nothing personal about “the Lord our God.” It doesn’t locate godliness. Somebody outside of us — a male, maybe Moses — is ordering us (“Hear, O Israel!”) to hear that the Lord is our God. Ughh. It’s unilateral, uni-directional. My “Listen, Israel” is very internal, it’s preparing us for something beautiful, something whispered and inclusive and complete, something so holy.

Schnur: It’s a mean and frightening world out there, a mutilated world. It’s imperative that humanity locates the divine within itself.

Lieber: Within Herself. Now we come to the fourth word, the fulcrum word: “b’kirbainu” — within us, among us, in our midst, in our inmost being. Wow. We’re expressing this to each other. “Hey, it’s within us!” It’s a revelation. No one told us this before, that it’s within us. At Sinai, they made a mistake. They really wanted to see a God. I think the word “b’kirbainu” came to me from the prophet Zephaniah: “God is in the midst of thee” is the standard translation [Zephaniah 3:17].

Schnur: But Zephaniah goes on to call God the “Mighty One who will save.”

Lieber: Whoa. That does not at all take us where we want to go! We need Oneness, not a One that’s Other, who “saves us” from outside of us, who is a separate entity. We’re part of the One. I don’t want a God who’s making something out there, who “forms light and darkness” — a God outside. I am part of God. I don’t care if God is male or female, or male and female, what I care about is that I am part of God.

Schnur: I need to go back to the uni-directional God for a moment, to the God who has a unilateral relationship with us. What if our relationship with that God were really reciprocal — if that God gets changed by our commitment, by our listening? If listening makes us equal? I need to quote the whole Levertov poem, to re-title it “Sh’ma”:

You have my

attention: which is

a tenderness, beyond

what I may say. And I have

your constancy to

something beyond myself.

The force

of your commitment charges us — we live

in the sweep of it, taking courage

one from the other.

Lieber: Oh, the idea of God taking courage from us is just amazing. There is no God without us; God needs us. When I was working on my dissertation, I found that the biblical God didn’t always know what God was supposed to do. In the book of Exodus, God needs Moses’ help to find His/Her position. We’re still watching the process of God’s growth and development, of God’s maturation. It hasn’t ended. My Sh’ma certainly doesn’t declare that God is complete.

Schnur: But the last word there — “Ahat” — certainly feels summative.

Lieber: Yes, this is the word that started the Shekhinah Sh’ma for me. It’s the feminine form of the word “one.” “The Shekhinah is One.” And what’s wonderful about it, as compared to the masculine form of the word, is that it starts with the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet and ends with the last letter of the alphabet. When I first realized this, while sitting in the library, I was beaming. I’m still beaming!

Schnur: It makes you happy.

Lieber: In the library, I was like a holy fool, a meshugeneh, talking to myself and the holy Hebrew letters. We are the beginning and the end. No matter what you do, it comes back to a beginning and an end. “Ahat” ties up the package, the doxology. And this alpha-to-omega word, in the feminine, happens to mean “one.” And we run all over the place shouting these words: We teach them to our children, and bind them upon our arms and heads, and write them on our doorposts. We put them everywhere so we don’t forget.

Schnur: “Listen, Israel, the Shekhinah is in our inmost being [is among us], the Shekhinah is One.”

Lieber: Yes. I don’t want the traditional Sh’ma, the traditional declaration of faith, posted everywhere. It takes our freedom away; it’s belittling. It severs us from ourselves. Women don’t want a big God up over us. The Shekhinah Sh’ma meets women where they already naturally are: in dialogue, in reciprocity, in inclusive and eternal oneness. This Sh’ma affirms what’s already ours: the prayer within.

Schnur: The inside/outside/everything/the earth/all of it.

Lieber: The “aleph” to “tof ” — the A to Z. The One.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...