Tag : mothers

July 27, 2020 by admin

Shopping: A Eulogy

Loehmann’s, long ago

RETAIL: AN INTRODUCTION

Picture, if you still can, the packed dressing room of a Loehmann’s, in the days before that deep-discount clothing emporium, its stores for decades a New York shopping icon, shuttered its doors. The lighting is grey, fluorescent, unflattering. But never mind, it signifies the business at hand: the sacred and profane ritual of communal shopping.

Hooks and clothing racks line the dressing-room walls, but the focal point of the space is a wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling mirror, reflecting dozens of pirouetting, preening bodies. Women. Women of all shapes, colors, sizes and ages, cellulite visible, in various states of undress: pulling their legs through pants, shimmying the fabric of dresses down over their hips. They are talking to each other (even to strangers) as they don their apparel: “Mom, that looks great on you!” “Too roomy, honey.” “Does it come in another color?”

This scene, once so common, marked by its fleshiness, its commingled breath, its total lack of privacy, and its awkwardness, is the quintessential pre-pandemic shopping memory. It’s as far from today’s click, order, then-snap-a-selfie process for purchasing clothes as one can imagine. Perhaps the intimacy of it all, even the overbearing qualities of that intimacy, may draw out a surprising yearning in those who recall it. Because now it’s not just Loehmann’s we mourn, but the fact that we cannot gather in that way, or any way, for a long time, or maybe ever.

Loehmann’s was one of the victims of the pre-Covid-19 “retail apocalypse” that was in full force even before the pandemic hit, a sign of our further march into late-stage capitalism, in which even the leisure of a quick in-person browse was becoming too leisurely for most time-strapped consumers. Thus for many of us, each chain that closes or is diminished— Lord & Taylor’s flagship store, Loehmann’s, Sears, J. Crew, Neiman Marcus — is not merely another famous brand name shuttering its doors, or retrenching. It’s a relic of another time, with memories that transcend clothes.

Stores-as-destinations, from upscale boutiques to a hip thrift store, provided communal spaces where women could be together, learn from each other and participate in an intimate treasure hunt. Spaces where our mothers and aunts and grandmas transmitted to us their concept of taste, of body image (for better and often for worse), of what kind of woman they wanted us to be.

So what will we do now?

Well, it’s complicated. Because the death of retail isn’t just the story of a lost way of life. And there are threads of hope in the fabric of this ruin: think of the hand-sewed masks or the way new companies are blasting “handmade in the USA” on ads across the internet. Think of all of us, as lockdown and distancing marched on, stepping back from consumerism as a form of cheap therapy.

Indeed, as we look at what clothes and shopping might be in the future, it’s not all loss and alienation. As those dozens of homemade, hand-sewn masks on Etsy show us, our current moment allows us a new intimacy with the people who make things for us—our friends or friends of friends with sewing machines and patterns or factory workers whose locations and incomes we are aware of—that could signal a new balance when the pandemic dust settles.

“The shutdown is forcing a rethinking of production and consumption within the fashion industry, and it’s unfortunate that it took this long for these structures to self-examine,” says Julianne Escobedo Shepherd, the editor-in-chief of Jezebel and a longtime fashion industry reporter. “For years, luxury fashion has forced designers to produce to an increasingly impossible schedule, siphoning creativity and creating a surplus that dictates the speed and urgency of more affordable fast fashion outlets to replicate it. It’s long been time for fashion to slow down. This schedule is simply unsustainable, from the higher-end fashion designers to the workers, often in inhumane sweatshop conditions, who produce cheap replicas.”

Shopping, like everything else we’re mourning in this strange suspended moment, may never be the same. Can we be appropriately mournful of what we’ve lost—the touch of fabric, the self-inspection in store mirrors—while looking to a future of consumption that is fairer and more thoughtful than that recent past?

MOTHERS AND DAUGHTERS

“The department stores, which have been failing slowly for a very long time, really don’t get over this,” Mark A. Cohen, the director of retail studies at Columbia University’s Business School, told the New York Times this spring, as the shock of pandemic settled in. “The genre is toast, and looking at the other side of this, there are very few who are likely to survive.”

Alexanders. Marshalls. A&S. Macy’s. B. Altman. The May Co. in Ohio, Donaldson’s in Minnesota and more. Just mentioning any of these names brings up stories for so many: often about mothers and daughters, or grandmothers, or girlfriends. Personally, each name has a new flavor for my New York-bred self: I recall the stately Lord & Taylor flagship, where my entire family used to go for the annual sale, or fancy Henri Bendel, an impossibly trendy outpost where my teenage friends and I begged salespeople for perfume samples. And then the thrift stores in Greenwich Village where generations of teens (including mine) tried on flared jeans and polyester shirts, experimenting with gender and social presentations. All these memories are so deeply tactile, marked by careful sorting, touching products, even if we didn’t buy.

Rites of passage and important occasions have long been marked (for those who could afford it) by the ritual of buying clothes together, with other women who would join together to get the bat mitzvah dress, the prom dress, the wedding dress. Nice new shoes for the beginning of the school year (will those ever happen again?) or a blazer for a first job interview. The shopping was often bookmarked with lunch. It was a tuna melt and tomato soup for me and my mom.

“My grandmother and I had a ritual of going to A&S department store in downtown Brooklyn, shopping together for an outfit and then heading over to Junior’s to split a sandwich and have cheesecake. We usually did this on Labor Day Weekend,” says Aileen Weintraub. A fancy lunch in the department store’s own restaurant was often an extra-special treat. Catchphrases might be coined on these trips: Alix Wall recalls her grandmother saying “it would be a crime to leave it in the store” when she came across a bargain at Alexander’s in Paramus, New Jersey.

Sometimes our memories were more mixed. Judy Bolton-Fasman associates Lord & Taylor with “revenge shopping,” a trip her mother took after a quarrel with her dad, spending money to strike back at perceived injustice and then hiding the results in the back of the closet. But still, she says, it was a way of learning about her mother’s “aspiration to a better life,” the store symbolizing “the epicenter of polite humanity.”

In a moving tribute to shuttering department stores, writer Andrea Atkins describes the trips she took with her mother to these palaces of consumerism. “In the department store, my mom inculcated in me her sense of taste, decorum, and style… her values, financial sense, restraint, and sometimes, determination,” she wrote at the website Next Tribe. “I learned what she yearned for.”

Sometimes the brand name or the store itself didn’t matter: it was the physicality of the experience itself. Boutiques and thrift stores, now also in deep danger, were about curatorial fashion, the store as an expression of identity and ingenuity.

Shoe stores for growing children had a tactile value, too: “I think often of shoe shopping with my mom as a kid and her pressing on the toe to see how much room to go I had,” says Courtney Stephens. “That feeling of being given space to expand into, in this very functional way.”

JEWS INTERTWINED WITH FASHION

None of these experiences are unique to Jews, or to women, or to Jewish women—there are certainly equivalent male rituals like the bar mitzvah suit and quinceanera dresses, communion outfits and garb for other non-Jewish rituals that make shopping trips sacred for many groups.

And yet history shows us that Jews and fashion in America have been intertwined on every level: from the women and girls trapped in the Triangle Shirtwaist fire, to the garment workers who organized in that tragedy’s aftermath, to the stereotype of the shopping-bag-laden so-called Jewish American Princess, deconstructed from time to time in Lilith’s pages.

“As early as 1890 almost 80 percent of New York’s garment industry was located below 14th Street, and more than 90 percent of these factories were owned by German Jews,” according to A History of Jews in America, condensed at MyJewishLearning.com. More numbers follow: “Immigrants were attracted by jobs and by Jewish employers who could provide a familiar milieu as well as the opportunity to observe the Sabbath. By 1897 approximately 60 percent of the New York Jewish labor force was employed in the apparel field, and 75 percent of the workers in the industry were Jewish.”

It goes on: “In 1880, 10 percent of the clothing factories in the United States were in New York City; by 1910 the total had risen to 47 percent, with Jews constituting 80 percent of the hat and cap makers, 75 percent of the furriers, 68 percent of the tailors, and 60 percent of the milliners.”

Some of the biggest names in the department store world were Jewish: from the venerable and frighteningly posh Bergdorf Goodman to A&S’s Abraham & Strauss, Gimbel’s, Filene’s and Kohl’s, to name just a few. Many of these dynasties began with peddlers, tradespeople or shopkeepers who vaulted into the “rag trade” big time.

But if women got a foothold on the power ladder as fashion buyers for these stores, and on their sales floors, the dynasties were largely male. The beloved television drama “Mad Men” even referenced this, by creating cult-favorite character Rachel Menken, the Jewish daughter of a department-store dynasty who wanted to take charge of the business and was met with skepticism and sexism by the goyishe men in the advertising industry, not to mention her own family.

And on the other end of these growing industries it was women who were at the sewing machines. In the early days of Jewish immigration to America, sweatshops crammed Jewish women, men and even children together on the Lower East Side and elsewhere. Jewish women counted heavily among the tragic, neglected 146 workers dead in the notorious Triangle Shirtwaist Fire in 1911, which drew national attention to inhuman conditions in sweatshops and factories.

In its wake, the famous Uprising of the 20,000—the New York Shirtwaist workers strike of 1909—became one of the flash points of Jewish feminism, socialist feminism and labor organizers in general. Led by Jewish communist firebrands Rose Schneiderman and Clara Lemlich, the successful strike changed the garment industry in America.

Yet it’s hard to ignore the fact that while some American women, Jewish women among them, moved from the sewing machine to positions in front of and behind the sales counter, the stitching labor itself didn’t disappear; the women wielding needles, doing piecework in factories, simply moved elsewhere. In the 1990s, the ascendant students-against-sweatshops movement drew Jewish students into activism. They called attention to the overseas labor practices of companies like Nike, and more, enabled by new “Free Trade” agreements. I spent a summer leafleting on 57th street, warning consumers that entering the Niketown store was tantamount to abetting oppression, even slavery.

We learned that the people suffering under these conditions were mostly women, sewing monotonously, locked in, discriminated against if they got pregnant, denied bathroom breaks—100 years after the Triangle Shirtwaist fire and the changes it wrought in U.S. fair-labor laws.

For me, it is hard to reconcile the very human love of fabric, of shopping, of seeking out communal space, with the exploitation behind it. My generation of feminists seized onto the words of second-wave critic Ellen Willis, reminding us that shopping, for women in a sexist world, can’t be criticized as mere empty consumerism. “When a woman spends a lot of money and time decorating her home or herself… it is not idle self-indulgence (let alone the result of psychic manipulation) but a healthy attempt to find outlets for her creative energies within her circumscribed role,” she wrote. “Consumerism as applied to women is blatantly sexist…. When we create a political alternative to sexism, racism, and capitalism, the consumer problem, if it is a problem, will take care of itself.”

ALIENATION AND COMMUNITY

Willis was well-versed in Marxist theory, which—and here I’ll be reductive—posits that the further we are swallowed into capitalism’s maw, the deeper our alienation: alienation from the products of our own labor, from our fellow workers, and ourselves, our essence. If the shopping trips that marked American middle-class life since WWII epitomized that alienation in a sense (we were alienated from the menial sweatshop work that went into making our clothes), we were also connected to each other through these rituals. As capitalism continued to accelerate, the problem continued to grow worse. At department stores, American-made clothes with the honorable UNITE! Union Label, which my mom had taught me to seek out on our shopping trips, grew harder to find.

“Fast fashion”—cheaper, more ubiquitous, more disposable—became the norm, and the old chains started to fail. For today’s shoppers, the move from the home-like spaces of department stores and boutiques to using computer keyboards and Paypal, and buying ever-cheaper “athleisure,” like stretchy leggings, to self-soothe takes us even further down that path, alienating us from physical joining together.

Once or twice, on shopping trips that had become rarer and were less and less pleasant, I found myself musing on the change. My recollection was of the department store as a space, as a sort of semi-private, semi-public commons. As a child, I used to sit on the floor happily under clothing racks while my mom looked for deals. As a teen and young adult, I found in department stores a place of refuge, with their expansive ladies’ rooms that contained couches and countertops for makeup application, their benches in the dressing rooms and scattered throughout the floor. Of course, finding such a refuge was contingent on race and class status, but if you could find it, it was heaven. During a bad period at an old job I used to slink off at lunchtime to the Macy’s shoe department, where I could stand amidst racks of discounted high heels I’d never wear and take a deep breath or call a friend or my mom for solace.

But those days are gone: even the department stores that remain are slick, expensive, with few benches and no nooks or crannies for hiding. Like other, homey spaces New York was already chasing out—dive bars and diners and gritty music venues—they were losing the battle.

Online shopping had arrived. “One of the major issues with online shopping is that it’s easier for anyone to procure clothing produced under inhumane conditions, without much knowledge about how the garments are made,” says Escobedo Shepherd. “Inexpensive, trendy clothing is a huge boon for people in lower income brackets who want and deserve to be as fashionable as their wealthier counterparts, but the whole system—from a high-end label’s eight or ten seasons per year on down—contributes to inequity across the board, not to mention is environmentally destructive.”

Understanding the exploitation behind fashion had already made my genuine nostalgia arrive with a chaser of queasiness. With climate change on the horizon and more and more reports of exploitation abroad, impulse shopping for me had been getting more and more fraught before Covid-19. (I was still doing it, just with more guilt.)

The devastating 2012 Dhaka factory fire, at a sweatshop in Bangladesh, reminded me so much of the Triangle Fire. It was followed a year later by another catastrophe with a toll: a factory collapse that killed even more workers. This marked the end of my flirtation with fast-fashion chains like H&M. I continued hunting for deals so good “you can’t afford not to buy,” to quote my grandmother and yours, at discount retailers like Marshalls and TJ Maxx, justifying the fact that these were trendy pieces from a few years back that would float around or be trashed if they weren’t re-sold.

Yet beyond that, I had made an even more stringent effort to change my own habits, beginning mostly to patronize three or four online shops that claimed to be eco-friendly, ethical and, ideally, made domestically (some even showing photographs of the dressmakers) allowing me to rely far less on sweatshops that oppress other women and more on clothing whose sources and resources I knew—or thought I did. Transparency and small-batch sewing are the new trends in fashion, and this may be a step forward, but maybe a step back if you think of Ellen Willis. It seems to be linked, at least on Instagram, with a mom-perfectionist lifestyle: an almost performative level of concern about the purity of the products you and your kids consume.

And yet the benefits of these small, direct-to-consumer companies go beyond the supply chain: for gender-noncomforming people, for those who were shamed for their size, for disabled folks, many of these shopping rituals I remember fondly carried pain and exclusion. Online boutiques and companies have been popping up to serve niche groups that wouldn’t necessarily have found a home in a department store.

Now with the pandemic, many of us are shopping for masks for our families. I’ve tried to buy American-made, organic cotton masks, or shopping directly from women artisans on Etsy, recommended by friends who are using their hands to create clothes for us. But no change comes without its cost: “There are more sustainable, popular, recycled/vintage platforms like Depop and Etsy that cut down a bit on this process, though there’s still mail waste (and warehouse and mail worker exploitation!) to consider,” says Escobedo Shepherd.

In the “someday” many of us dream about, will we recreate spaces to wander, to touch the garments we’re considering? Or will we continue down the road we’re on, away from in-person shopping? Will we wear outrageous clothing on the street [see sidebar] or will homespun become a trend again? I know that I will dearly miss the feel of fabric between my hands, the click of hangers as I push them aside to look for the diamond in the rough. But I don’t think I will ever be able to participate in those rituals again without wanting even more of a connection that I once had: not just a connection to the people I’m shopping with and for, but also a connection with and understanding of who made the items I’m touching.

- No Comments

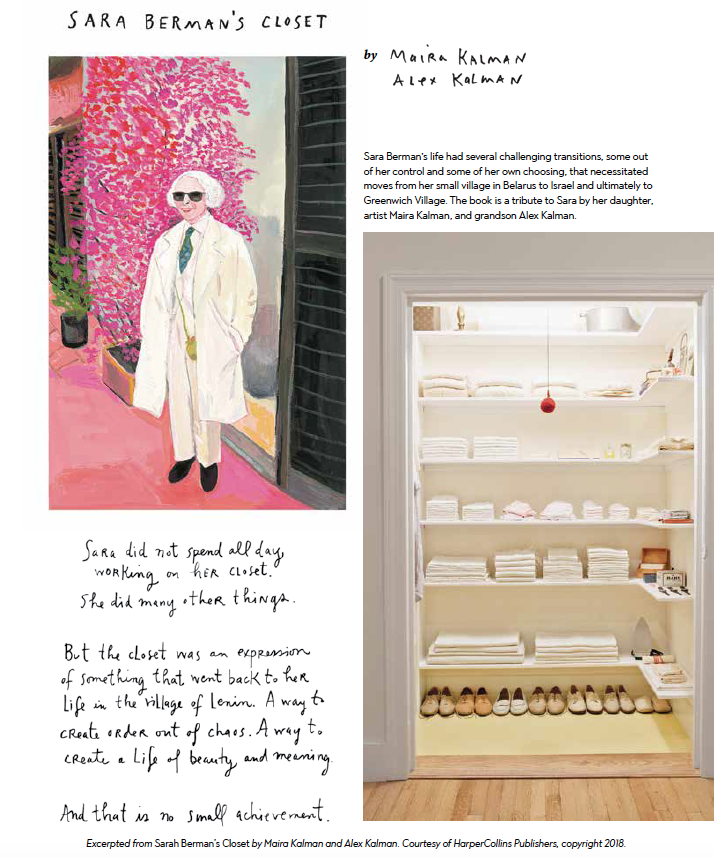

May 2, 2019 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

The Object of Your Affections: What’s a Baby Between Friends?

Two best friends undergo a bitter falling out and a tearful coming back together. But this is no ordinary rapprochement—because one of the women asks her friend to be the surrogate who carries her child. Author Falguni Kothari talks to Lilith’s fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the complex, delicate nature of such a relationship, and how it set the plot for her new novel in motion.

- No Comments

January 10, 2019 by admin

After Years of Silence, a Phone Call — and a Visit

I jumped awake when my phone rang, and my heart stopped when I realized that it was my mother calling. I couldn’t see her name or number on my screen, just the word “Blocked,” a remnant of a time that had ended only a couple of days earlier, a time when she and my father had removed themselves from my life.

My grandparents had warned me that she would be calling to make amends, so I was somewhat prepared to see “Blocked” pop up. But I honestly didn’t expect she would actually call. Over the past few years, neither of my parents had been my parents—so I assumed this would be yet another false hope. But she called.

One of the first things that my mother told me was that I “still sounded like a baby.” As a person who hasn’t had the luxury of being someone’s baby for a very long time, it infuriated me. But when she asked if she could come visit me in Colorado, I said yes. I told myself that I was only saying yes because I wanted to convince her to let me see the kids. I didn’t let myself entertain the idea that I wanted to see her, or that she truly was interested in knowing me again.

In the days leading up to her visit, I reflected on all that I had lost, all that she and my father took from me. I recalled the trauma of our separation which was caused by a variety of factors, but in part, my decision to embrace my Jewish heritage in the face of deep disapproval. I remembered all the nights that I woke up sobbing, missing my siblings with a ferocity that felt like dying. And it filled me with rage.

Something soul-destroying happened to me when I became estranged from both my parents. I felt like a person whose history, whose childhood didn’t even exist. I felt like someone who was born from nothing but air, not flesh and blood. I would look for childhood pictures and remember that they were all in a house that I and my grandparents were no longer welcome in. I would tell people that I had brothers and sisters, and it felt like a lie. The faces I saw in my mind were frozen in time, not the faces of the children my siblings had become, but the faces of small children waving as they sent their big sister off to school, not knowing that three years would pass by before they saw her again.

I would look around at the people who had become my family—my partner, my grandparents, my friends—and I wouldn’t see myself in any of them. Every time I saw my partner interact with his parents, it felt like ripping out a page from a storybook in an alternate universe, one where my parents could love me without reservations and with consistency.

I knew that my grandparents would do anything for me, but my grandfather wasn’t my biological grandfather. I didn’t see the genesis of myself when I looked at him, although I did see someone who loved me very much. And though my grandmother had saved my life more than once, with her petite frame, light skin, green eyes, and auburn hair, so unlike my own dark skin and eyes—sometimes she too felt like the opposite of me. I felt like that little baby bird going around asking people “Are you my mother?” But I wasn’t a cute character in a children’s book. I was someone whose parents had walked out—which I felt made me a subject of both fascination and pity.

I didn’t feel real. But then my mother walked through my apartment door. And I saw myself. My mother and I look exactly alike, an eerie phenomenon of duality that exists throughout her family. It always shocks people. It shocked my partner, who commented on how beautiful we both were, but how odd it was that we had the same face, the same hair.

I don’t need people to tell me that I’m my mother’s twin. Even when things were good, she was more of a sister than a mother. She had me at 22, and throughout my childhood I was her best friend and confidant. I always felt like it was my responsibility to protect her, but I didn’t know what I was protecting her from. I just knew that she was deeply sad and deeply upset about everything in her life, including me. It would be easy to say that the cruel way she chose to manifest her disappointment in me proved she didn’t love me. This is the story that makes the most sense when I review the evidence.

But as a writer, I am learning that the obvious story is almost never the story that needs to be told. I am learning that truth is almost never swallowed easily. I am learning that we can be most fulfilled by accepting the things that scare us.

In our time apart, it was surprisingly easy for my mother to become a monster in my mind. I had a lot of material to make her into this monster—hell, one time she even told me she was one. Other people who had also been hurt by her felt the same. I thought I had my mother figured out. And seeing her this way made easier to cope—after all, who could love a monster that couldn’t love them back?

I’ve always known that I looked exactly like my mother. But what always terrified me was the possibility that I might be exactly like my mother. The idea of that I had some evil lurking in my soul that would cause me to lose the people I love ate away at me. Maybe my parents were justified in abandoning me, maybe I wasn’t worthy of anyone’s love.

But when I saw my mother this weekend, when I talked with her, I did see myself. I saw someone who was deeply and irrevocably hurt by her own mother. I saw a black woman who struggled to be valued by her family, and by society. I saw someone who was desperately looking for someone to protect her, and going about it in all the wrong ways. I saw myself. And this time, I didn’t flinch. I’m not big on forgiveness, but in this moment, forgiving my mother felt like forgiving myself. Forgiving myself for being impacted by a world that doesn’t value women like me. Forgiving myself for “acting crazy” after I was violated by men and by my mother. I needed to understand her, so that I could understand the places I had been, and the places I hoped never to reach.

It was so easy to make my mother into a monster, and she became a vessel that held all of my pain.

But I saw that the pain she had inflicted on me had come from her own mother. And more than anything else, more than revenge, more than the last word, I just wanted peace. I wanted and needed to know what to do to end the cycle.

My mother seemed like a changed person. She apologized to me. She told me she loved me. She’s done that before, but I think I might choose to believe that this time is different. At the very least, it’s different on my end.

She told me that I could come visit my brothers and sisters. I’m looking forward to hugging them, to seeing the wonderful people they’ve grown into. I’m looking forward to grabbing a few of my baby pictures. I’m looking forward to feeling whole.

Nylah Burton is a writer from Washington D.C. She is currently based in Colorado.

- No Comments

January 10, 2019 by admin

Late Revelations: When Our Matriarchs Lose Their Filters

At the age of 90, my mother started speaking very differently about her mother. Her jaw tightened when she mentioned her. “All she cared about is money!” she would say. “She was competing with Rockefeller! She wanted to see how big the number in her bank account could get!” On the dinette table stood a matchbook- size photo of my grandmother’s pallid face in a babushka, her dark eyes huge and worried. She seemed, frankly, locked away, pleading to be released. The snapshot had been there, imploring, since my grandmother died 30 years ago. Now it vanished.

At the age of 90, my mother started speaking very differently about her mother. Her jaw tightened when she mentioned her. “All she cared about is money!” she would say. “She was competing with Rockefeller! She wanted to see how big the number in her bank account could get!” On the dinette table stood a matchbook- size photo of my grandmother’s pallid face in a babushka, her dark eyes huge and worried. She seemed, frankly, locked away, pleading to be released. The snapshot had been there, imploring, since my grandmother died 30 years ago. Now it vanished.

Can there be such a thing as selective dementia? My mother’s mind remained clear in all other matters. This was baffling.

Her mother, my grandmother, had been a widow who’d supported three young children by working as a seamstress in the Bronx. My mother was only two when her father died of tuberculosis. The family was poor. In my girlhood when I visited my elderly grandmother, half-finished dresses still lay piled on the table. Sometimes my grandmother was on her knees, a visitor on a chair before her, as my grandmother positioned a hem. Later, when she could no longer sew, she made 25 cents an hour stuffing records into record-jackets, alone in her apartment.

“She was a slave!” my mother often said bitterly of her mother, while I was growing up. “She worked from before dawn until midnight.”

“Well, what about Saturday?”

“Saturday she went to shul and then, in the afternoon, to Crotona Park.”

“Did she read, when she was in the park?”

“Are you kidding? She was exhausted. She didn’t read. She sat.”

This always surprised me, because I recalled my grandmother’s glass-front bookcase crammed with volumes, all in Yiddish or Hebrew. To be too tired to read! I couldn’t understand a life that didn’t have ample reading.

Mameleh my mother used to call her mother. We lived about eight blocks away. They would sit in our kitchen and drink tea. My mother once forbade me from accepting a quarter from her mother, who needed it. When I saw them, I saw their tenderness. They didn’t hug, but they often kissed on the cheek.

And so, in the beginning, and for a long time after, I dismissed my mother’s late-in-life negative view of her mother. I once asked a psychiatrist about it. “It sounds so warped to me, this brand new version of her mother. Do you think there’s anything to it?”

The psychiatrist frowned. “Well, most people don’t wait until they’re 90 to start resenting their parents,” she said, which I took to mean that if there was actually something to resent, my mother would have found it decades earlier.

So I dismissed this version as nonsensical. But as the years passed—eight, so far—my mother continued to speak of her mother in the same negative way, and I began to concede that there might be something to her version, especially as details emerged. “She didn’t care about me,” my mother told me. “I had my tonsils out when I was eleven years old, and she didn’t come.

There was another girl near me who’d also had her tonsils out. I heard her say to her parents, ‘Give my leftover ice cream to the orphan girl’. That’s how I seemed. An orphan! So they gave me the ice cream after she licked it.”

She also said, “When I was six I had bronchitis, and the hospital sent me to a Catholic hospital in Brighton Beach. I was there months. My mother came to visit only once, at Passover, and brought me a box of matzah. That was the last thing I needed! The other kids were already sticking pins in me for being a Jew! What did I need with matzahs then?”

She’d never told me these stories as a child or young adult. Only in middle-age did I get to hear them. And for many reasons I felt I was lucky to have a mother who’d lived so long.

Because my new understanding is that in advanced age, defenses thin. In old age my mother was giving me a portrait of her internal world as a very young girl. How else to understand a mother who is too busy to give attention to her toddler? She must be money-hungry! Insatiable. How else to understand a woman who doesn’t visit, but remains obsessed with her sewing machine? I am getting the version of her mother that my mother experienced when she was a child.

“I never could never find my love for her,” my mother told me one night, when I had ordered a glass of wine for her over supper. We were staying at the Marriott on my husband’s business points; my parents’ apartment had bedbugs, so we shared a bedroom for the first time in our lives. My mother didn’t drink alcohol, even at Passover. “It feels like floating!” my mother reported back, laying in the next bed over. “It’s a very nice feeling!” Then she confessed to me how she felt about her mother.

Hearing this, my own childhood finally made sense. For my mother had never enjoyed reading to me or, it seemed, paying me much attention. One of the few times she did read to me, The Cat in the Hat borrowed from the Francis Martin Library, she leapt up after six or seven pages, exclaiming, “You have no idea how it dries the throat! How much it hurts!” before she hurried out of the room to the sink.

Why did it pain her so much to read to me? I believe now I know. It sometimes hurts to give what you haven’t been given. She was as bored with me in my early childhood as her mother must have appeared to be with her. Happiness seemed a zero-sum game to us both, and if I was happy, I must be taking from her.

I felt quite mediocre, as a child. My accomplishments, when they began in my senior year of high school, came as a surprise to me, and always seemed a fluke. My intelligence, discovered so late due to a lack of early mirroring, seemed extraneous, a fun hat tied to a dull head. But now in my mother’s advanced old age, I feel that I have been given a precious lens.

Nor is it only with my own mother that I see this phenomenon of age exposing a person’s emotional core. My husband’s mother, who in fact does have dementia, often rocks in place, moaning yearningly, “Mama, Mama, Mama!” During her life of cogency she was a loquacious but emotionally aloof woman. Conversation, always filled with laughter and chatter, seemed a method to keep others at a distance. She appeared irritated by others’ needs. She was a woman with a voracious appetite, a secret eater, and her favorite thing was to be left alone to read, as my husband jokingly called them, “sagas of Hebrew passion.”

But in her mid 80s, when her mind gave way, she started saying “Mama.” Now it is almost all she says. I may be making too much of this, but I don’t think so. I think she is finally voicing the painful longing that hid behind her obdurate affect. She once told me that her mother advised her, “Nobody wants to hear about you.” Her tone at the time was impassive, her story told with a shrug. I couldn’t imagine what it felt like to hear that from one’s own mother. But now she is showing me.

How grateful I am for these late revelations. They give me pain, yes, but knowledge can be healing. If my mother had passed away before she started resenting her mother, what a loss for us both! Now, what has emerged is ambivalence, for I do believe she experienced for her mother both love and hatred. My mother suffered early deprivations that made her think that a poor woman supporting her family was in truth avaricious and cold, hoarding her assets. Consigned to the hospital ward, how lonely she must have felt, wanting the woman who apparently didn’t want her. Back home she was ignored, even neglected, while her mother bent over the sewing machine. A shard of my mother’s emotional truth flies down through the years and illuminates my own childhood. I understand now the strange absences that shaped me.

In my earliest years I recall being in a playpen, a crib, or strapped into a high chair, always at a distance from the besieged woman I craved. As an adult I was surprised to discover that “What did you learn at school today?” was considered a standard inquiry. A sense of inferiority—my own mother was uninterested in me—has haunted me, and effloresced in various kinds of mundane masochism that only midlife let me conquer.

But now, discovering my own mother’s longing has freed me to feel empathy. Here is the girl my mother was, waiting alone in her hospital bed for the woman who didn’t appear. That lonely little girl didn’t go away. She’s still there. My mother’s old age introduced me to her. I take my mother’s hand as she sits in the wheelchair. “I love when you visit,” she says. “Me too,” I answer, truthfully.

When I leave her, I am emptier and fulfilled, enlarged by the echoes of the women in my family, by my mother in the present and the past.

Bonnie Friedman is the author of the bestselling Writing Past Dark: Envy, Fear, Distraction, and Other Dilemmas in the Writer’s Life and, most recently, Surrendering Oz: A Life in Essays, which was longlisted for the PEN award in the Art of the Essay.

ART CREDIT: “A QUIET ROW OF WOMEN” BY ANDI ARNOVITZ

- No Comments

October 3, 2018 by admin

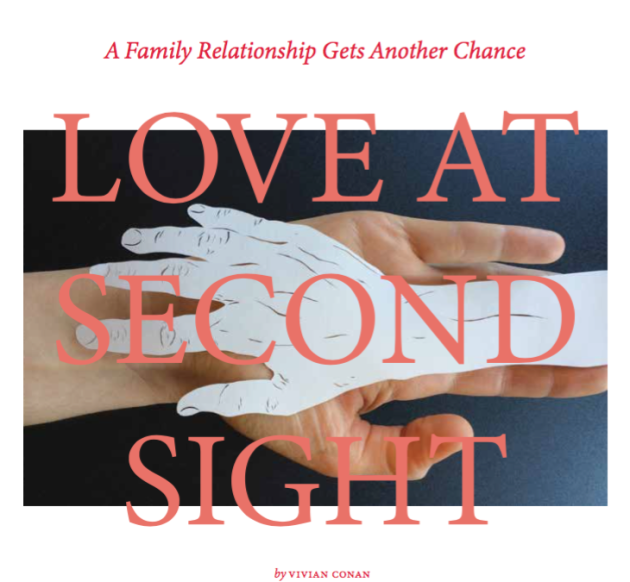

Love at Second Sight

When I was a child, my mother gave me orange slices to suck when I threw up, to take away the bad taste. She sat on the floor, pincushion in hand, to shorten the hemline of my junior-high graduation dress. Other times, she turned my world upside down by screaming, “Get out of my sight, you fucking bastard! Go shit in your hat! Your name is Mud!” She hit me with a wooden hanger sometimes because, “It hurts me when I hit with my hand.” She also tried, with varying degrees of success, to act as a buffer between my strict father and me. In this, I felt we were allies.

When I was a child, my mother gave me orange slices to suck when I threw up, to take away the bad taste. She sat on the floor, pincushion in hand, to shorten the hemline of my junior-high graduation dress. Other times, she turned my world upside down by screaming, “Get out of my sight, you fucking bastard! Go shit in your hat! Your name is Mud!” She hit me with a wooden hanger sometimes because, “It hurts me when I hit with my hand.” She also tried, with varying degrees of success, to act as a buffer between my strict father and me. In this, I felt we were allies.

Our relationship was complicated.

One afternoon when I was 15, I was shopping on Brooklyn’s Bay Parkway with my mother’s cousin Mildred. All at once, she clutched my arm and said, “Doesn’t that man look exactly like your mother’s first husband?”

Mildred had always been a little off. “My mother was never married before,” I said.

“You didn’t know?”

An hour later, my mother confirmed Mildred’s story with a simple, “Yes, I was.” My initial shock turned to joy at the implication. Only days before, I’d asked why she tolerated all my father’s raging and irrational rules. “I’m surviving,” she’d said, “I’m coping.” She spoke as if she had met her goal. She didn’t realize I was asking why she tolerated it for the whole family, not just herself.

“Who’s my real father?” I asked, “Daddy or your first husband?”

“Daddy. I didn’t have children in my first marriage.”

That ended my interest.

We didn’t discuss it again for 45 years.

When I was 30 and my mother was in her late 50s she retired from a career as an educator. Listening to the PTA president’s speech at her party, I gained a new respect for her. “When Mrs. Conan came to this school, our children could not read. Now our children read!” she said.

My mother soon started a new career, as an interviewer with the Social Security Administration. She also embarked on what would become a decades-long quest for personhood, reading self-help books and filling index cards with sayings like, “We expect from each other only what we are able to give of ourselves.” Over the years, I had felt alternately angry and cordial toward my mother, though never really close. Now I sensed she longed for a deeper relationship. While I understood what she was doing, I wasn’t ready for more intimacy. She didn’t push it.

Little changed until my mother’s early 80s, when she visited me for a sleepover in my summer bungalow. It was three years after my father’s death. As I was drying the dishes, she said, “On Yom Kippur, before you ask God for forgiveness, you’re supposed to ask the person you wronged. So I’m asking, do you forgive me for all the bad things I did when you were growing up?”

This took me by surprise. Our conversations usually consisted of news exchanges, telling each other about places we had been or errands we had run. I didn’t want a give-and-take beyond that.

“Yeah, I forgive you,” I said, dabbing a stray drop on a cup.

“That doesn’t sound like forgiveness.”

Her voice was one I’d never heard before. It was vulnerable. Looking up, I saw an earnest face that scared me. I wanted to bolt.

“I forgive you,” I repeated, meeting her eyes.

“That still doesn’t sound like forgiveness.”

Suddenly, I realized what a risk my mother was taking, and that she was in pain. I had the power to take it away or make it worse. I put down the towel, hugged her, and said, “I forgive you.”

She hugged me back, saying, “Now I know you mean it.”

I wasn’t sure how much I did mean it, though I was glad she thought I did, because I felt I ought to mean it. But in the months that followed, I felt lighter than I had in a long time. My mother had given me a gift. She had acknowledged that the things she’d said and done had really happened, and she knew that they were hurtful.

Until then, I had never wondered what made her the way she was. I’d been too busy surviving myself. Now I began to be curious about what had shaped her, and asked whether she would share her recollections. She was very willing to answer questions. In fact, she seemed to welcome them. Our exchanges, a few minutes here, a few there, added emotional depth to what I already knew.

My mother was the sixth of nine children born to the doting Greek-Jewish grandparents I called Nona and Papoo. I’d never imagined they might not have been that way as parents, being so preoccupied with paying the mortgage they couldn’t give much attention to any one child. My mother didn’t start school until she was seven, because Nona kept her home to care for her brother, four years younger. When she graduated from elementary school, Nona and Papoo came to the ceremony. Afterward, the three of them walked home together, the first time my mother was alone with both parents. She told me how proud she felt making her way down the block between them, for all the world to see.

Nona’s greatest wish for each of her daughters was a husband. My mother craved Nona’s approval, so, at 21, she married her college boyfriend. But Nona wasn’t pleased, because he didn’t have a job. The marriage lasted three years.

Two years later, my mother met my father. She was captivated because he spoke several languages, played chess, and listened to classical music, and because his attentions were a balm after her divorce. Nona was satisfied with my mother’s second match: he was a postal clerk. They were married in four months.

Things deteriorated quickly. When my mother bought an inexpensive dress without first asking my father, he took her name off the bank account. A sewing-machine operator in a factory, she had to turn over her salary to him, and he gave her an allowance for household expenses.

Then came World War II. My father left for Europe when I was two and my brother just days old. Within weeks, my mother got a job as a substitute teacher and opened her own bank account. When my father returned a year later, he resumed his role as the boss at home, but my mother kept her bank account and her career.

I asked why she had never divorced him. “I didn’t want to be unmarried,” she said.

In her late 80s, my mother requested my help managing her paperwork. Once a week, I drove from Manhattan to the Brooklyn house I grew up in. We sat at a bridge table in my brother’s old room and reviewed bills and bank statements, then went out to eat. She always insisted on paying, and on giving me a little extra for myself, because “It shouldn’t cost you anything to visit your mother.”

I looked forward to these visits. My mother felt our togetherness, too. “It’s love at second sight,” she said.

One day, in the course of a meandering conversation, she mentioned her first husband. I asked how the marriage had ended. “He left me for my best friend,” she said.

I visualized my mother as a young woman feeling the pain of abandonment and lost love. “How long did it take you to get over it?” I asked.

“I never got over it,” she said.

After dinner, as I began my drive back to Manhattan, I saw my mother in my rear-view mirror, waving from the top of the stoop. When I got to my apartment, there was her usual message on my answering machine. “Vivian, this is your mother. You just left. I hope you have a safe trip home. I had a wonderful time with you. And Vivian, I love you. Iloveyou, Iloveyou, Iloveyou. Bye-bye, Vivian.”

That night, I did an Internet search for Sam Langbert. After I determined he was still living—he wasn’t in the Social Security Death Index—I looked through directories and found a listing in Florida. I called my mother and told her I had an address for a man who might be the Sam Langbert she married. “Do you want it?” I asked.

“No,” she said, “but don’t throw it out.”

A week later, she called. “Viv, if you still have that address, I’ll take it.” She wrote a letter that began, “If you are the Sam Langbert whose mother lived on 18th Avenue in Brooklyn and whose father had a shoe-repair shop on 34th Street in Manhattan, near Macy’s, then I was your wife.”

Sam’s reply arrived in eight days. He wrote that he had thought of her often, she was a fine person, and he felt bad about what he had done. Her friend left him after a few years, and he had been married several times since. “So you see, I don’t have a very good track record as a husband.”

My mother answered, telling him she had been married 52 years, her daughter was a librarian, her son a psychologist, and she had three grandsons. She wrote that she had been a school principal.

“I wanted him to know I was successful,” she told me.

I asked how she felt having gotten in touch with him after all these years.

“I finally have closure,” she said, looking more peaceful than I had ever seen her.

Two years later, just before her 90th birthday, my mother was reminiscing about her childhood. “I have a picture of my mother in my bedroom,” she said. “And I look at her, and I thank her. I thank her for being my mother. I enjoy her more now, I think, than I did when she was alive.”

I was enjoying my own mother now, and glad she was alive to know it.

Vivian Conan has written for the New York Times and New York magazine. She has just completed her memoir, Losing the Atmosphere.

Art: “CONTACT” BY MAUDE WHITE, INSTA: @BYMAUDEWHITE

- 1 Comment

July 31, 2018 by Penny Jackson

I Couldn’t Divorce My Mother-in-Law

The Lilith blog presents original short fiction: “The Elephant in the Bush” by Penny Jackson

The Lilith blog presents original short fiction: “The Elephant in the Bush” by Penny Jackson

“Look,” my mother-in-law tells me. “There’s an elephant in the bushes.”

I turn to look where she is pointing. We are sitting on white deck chairs in a very suburban backyard in New Jersey.

“Do you see it?” She presses my hand. My mother-in-law, whose name is Ida, starts bobbing her head in the agitated way I know now so well.

“Of course,” I tell her, taking off my sunglasses and peering at the shrubbery.

“How funny. Not only an elephant. But a baby elephant!”

Ida is in stage five of Alzheimer’s disease. She is either a late five or early six. I’ve read the books her daughter has loaned me. The 36-Hour Day is the most popular book that is passed around from family member to family member.

- 1 Comment

June 12, 2018 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Isolated Mothers, Searching for Miracles

The reader knows by page one of Queen for a Day that Mimi Slavitt’s three-year-old son is autistic, but if anyone told her, she wouldn’t listen, because she doesn’t want to know—until at last Danny’s behavior becomes so strange even she can’t ignore it. After her son’s diagnosis, Mimi finds herself in a world nearly as isolating as her son’s. Searching for miracles, begging for the help of heartless bureaucracies while arranging every minute of every day for children who can never be left alone, she and her fellow mothers exist in a state of perpetual crisis, “normal” life always just out of reach. In chapters told from Mimi’s point of view and theirs, we meet these women, each a conflicted, complex character dreaming of the day she can just walk away.

Taking its title from the 1950s reality TV show in which the contestants, housewives living lives filled with pain and suffering, competed with each other for deluxe refrigerators and sets of stainless steel silverware, Queen for a Day portrays a group of imperfect women living under enormous pressure. Maxine Rosaler talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the true-life experiences that led her to write this book. (more…)

- No Comments

April 17, 2018 by admin

Silences Between Mothers & Daughters

WHEN MY MOTHER had her first episode of congestive heart failure, I was 46. The doctors prescribed various medicines and told her to exercise, and after a few days in the hospital the crisis seemed to be over. She took up swimming, which she didn’t like, and lived another 12 years.

I never knew how my mother felt about this experience, even though I was there with her through it all. It was some-thing to be handled, not discussed, and she seemed to adjust to her new condition without difficulty. I wonder now about the fear and anxiety she must have felt, and what it was like to be a divorced, aging woman, facing the prospect of living alone with a diseased heart. I wish I knew. But she was of a generation that didn’t talk directly about these things, and she was more interested in controlling her feelings than exploring them.

Still, I could have asked more questions. I could have gone beyond her proper, contained surface and encouraged her to open up. Having worked over a dozen years as a psychotherapist, I had the skill to do this, but I didn’t take the time. I told myself I was too busy. I had just moved to the West Coast, a half hour from her, and was transitioning into a new marriage and a new career as a publisher. My schedule was crowded with things to do and people to meet, and I was in a speeded-up state.

I settled into the role of the dutiful daughter, watching over my mother from a distance, making sure she had what she needed. Every so often I took her out for lunch or dropped by, and we spoke about family matters and the trips she sometimes took. I didn’t talk much about myself. Bruised by her rejection in the past, I was careful not to reveal any-thing about the disturbing issues I was facing in my new life.

Now that I am the age my mother was when she first became ill, I realize she must have sensed my emotional unavailability and known she couldn’t share intimate parts of herself with me. There was no space in our conversations for her sorrows and insecurities or her worries about the future, and in return, I didn’t seek her advice or solicit her wisdom. Perhaps she could see in my face that I was having difficulties, but we continued as though this wasn’t happening. Did words sometimes well up within her and get stuck in her throat, as they did for me?

I’m sorry my mother and I couldn’t speak openly during that time. We could have been of solace to each other. I look back at my middle-aged self and see how much I’ve learned since then about the importance of connection. With two middle-aged daughters of my own, I now know how it feels to be in my mother’s position. My relationships with them are more satisfying than ours had been and we speak with much more candor, but I too have experienced awkward silences and censored topics, wanting to say something but holding back, fearing that I’ll disrupt our connection or cause offense or somehow knock us off course. I’ve learned that it is some-times easier to listen to what they have to say than to reveal my thoughts or feelings. But there’s a price I pay when I hide in this way: I’m less known by them.

It took me a long time to realize that I silence myself with my daughters, but I’ve discovered I’m not unique in this way. My colleague Sandra Butler and I recently wrote a book about older mothers mothering middle-aged daughters, and in the process, we spoke in depth with dozens of women aged 65–85. To my surprise, most of them said they often feel unknown or unseen by their daughters.

They tell us about the reasons why this happens. Some fear their daughters’ anger, disapproval, or withdrawal, and say they are “walking on eggshells.” Others carefully circumvent the past so that old wounds are not reopened, or they’re ashamed of the mistakes they’ve made. We spoke with mothers who minimize their own success and accomplishments, fearing they might intimidate or overshadow daughters who are having difficulties, while others silence themselves because their daughters aren’t particularly interested in them, relating to them only as “Mom” or “Grandma.” And there are those who remain silent because they’re afraid of being seen as bossy and judgmental.

Mother-daughter relationships can be deeply satisfying and fulfilling, but often they are troubled because of the existence of their shared history. It’s hard for a daughter to ignore her mother’s pursed lips in the present moment when this reminds her of how her mother looked before punishing her as a child, and it’s hard for a mother to accept her daughter canceling a dinner together when it reminds her of the pain she felt when her offspring chose to live with their father and not with her after the divorce.

Mothers and daughters are deeply connected by a complex history. It’s assumed or at least hoped they will be able to talk to each other in an intimate way. It is all the more disturbing when they don’t.

Mothers often look back fondly to when their daughters were young and they felt they had fewer constraints on speech. As one told us, “I could say whatever I wanted in those days because I was her mother and she was dependent on me. I taught her Jewish values and the importance of family life, but unfortunately that didn’t stick. She hardly ever sees her relatives and doesn’t ask about them, and she works for a company that exploits its workers. I love her—I always will—and there’s a bond between us, but I have to be so much more careful about what I say to her now. Otherwise, I’m afraid I’ll lose her.”

At the heart of mothers’ concern is the fear of loss. As their lives begin to contract and their daughters move fully into their own with partners, children, careers, and community involvements, mothers sometimes feel left behind. This happens at a time when they’re more vulnerable, adjusting to the demands of their aging bodies and their changing circumstances. Contact with their daughters becomes increasingly precious and infused with meaning, and it matters more to them because they understand in a way they didn’t before that it won’t last forever. They don’t want to lose this most-important connection because of saying the wrong thing.

I’ve focused on mothers silencing themselves since it’s most familiar to me. But mothers are just half of a relation-ship’s equation, as I learned when my own fell ill, and daughters have a multitude of reasons for being silent. I, for one, carried a lot of resentment and distrust from the past, and that made me hold back on revealing myself to my mother.

Failure in communication is not inevitable because of shared history, however. Some relationships grow deeper as mothers reach the last decades of their lives and look within themselves and acknowledge their mistakes. No one is perfect, and when they are able to see the missteps they made through the years and apologize to their daughters, the door to forgiveness is opened. And then silence—the kind that feels like hiding or negating the self or avoiding saying the hard things—is no longer an issue.

I know about this because of talking with so many mothers, and I also experienced it myself. My mother softened as she aged and approached death, and began to express words of regrets. Once she told me she was sorry she hadn’t been a better mother, and another time said she knew mine had been a hard childhood. I didn’t need her to spell out the details. Her intention was enough; I began to trust her more and my love deepened, and I was able to apologize to her, too. And in so doing, I let go of being the stubborn, silent daughter I had been for years and forgave her and myself for all that had gone before. With that, we moved into a state of closeness we had never known.

Nan Fink Gefen is the publisher of Persimmon Tree: An Online Magazine of the Arts by Women over Sixty. Her most recent book is It Never Ends: Mothering Middle-Aged Daughters (She Writes Press, 2017) .

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...