by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Isolated Mothers, Searching for Miracles

The reader knows by page one of Queen for a Day that Mimi Slavitt’s three-year-old son is autistic, but if anyone told her, she wouldn’t listen, because she doesn’t want to know—until at last Danny’s behavior becomes so strange even she can’t ignore it. After her son’s diagnosis, Mimi finds herself in a world nearly as isolating as her son’s. Searching for miracles, begging for the help of heartless bureaucracies while arranging every minute of every day for children who can never be left alone, she and her fellow mothers exist in a state of perpetual crisis, “normal” life always just out of reach. In chapters told from Mimi’s point of view and theirs, we meet these women, each a conflicted, complex character dreaming of the day she can just walk away.

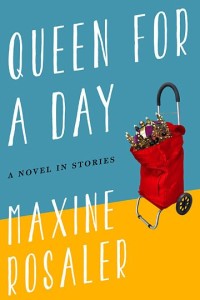

Taking its title from the 1950s reality TV show in which the contestants, housewives living lives filled with pain and suffering, competed with each other for deluxe refrigerators and sets of stainless steel silverware, Queen for a Day portrays a group of imperfect women living under enormous pressure. Maxine Rosaler talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the true-life experiences that led her to write this book.

YZM: These stories feel deeply personal; how closely are they based on your actual experience?

MR: All the stories were initially inspired by my life and my experiences and by the lives and experiences of mothers I have known. For some of the stories, in order to flesh out a character and make sure I got certain details right, I interviewed other women—some friends of mine, some not; some mothers, some not. The character who most closely resembles the real person on whom she is based is Mimi, who is, obviously, based on myself. However as much as Mimi resembles me, she is not me. She, too, turned into a character I was writing about. And Danny is very much like my son Benjy.

YZM: How long did it take to write this very personal book?

MR: I wrote the first draft of the story, “Sleepwalking Boy,” which is the first story in Queen for a Day, 20 years ago. Soon after that, I started mapping out the collection. I came up with ideas for a bunch of interconnected stories, and these ideas changed over time, as I met other mothers, and had new experiences and decided to approach a story from different angle. Aside from telling the story of the evolution of Mimi’s grief, one of my goals was to portray a range of different kinds of mothers, women who were interesting characters in and of themselves, who existed as real people, apart from their roles as the mothers of handicapped children.

I also wanted to create as complete a portrait as possible of the strange world these women had been forced to inhabit. Some of these stories were so difficult for me to write, it took me 15 years to get them where I wanted them to be.

And then, after writing at such a leisurely pace (completing two other collections of stories during that time as well), when Delphinium accepted my manuscript for publication, I suddenly found myself in a mad rush to turn the collection into a “novel in stories.” So for nine months, with very few exceptions, I did nothing but work on molding the collection into a cohesive whole.

YZM: Do you, like Mimi, feel the Jewish community is more accepting of children like Danny?

MR: That was my initial expectation. And I think to a certain extent it is probably true. I have a number of close friends in the Orthodox world—most of them are part of the small Haredi enclave a few blocks away from where I live, and I know how committed they are to each other, as a community. I admire and envy them for that. However, my son’s real-life experience at the yeshiva did not turn out to be what I had hoped it would be, because, for one thing, they were not able to address his very unusual combination of needs. For another, like Mimi in “The Story of Annie Sullivan,” I couldn’t afford to keep him there; so we never got far enough to test my theory out. Also, the religious aspects of Judasim never appealed to Benjy. Although, like Danny, he really did like learning Hebrew. So, also like Mimi, my initial dream of finding a readymade community for my son did not come true.

YZM: What do you hope the reader will learn, both about autistic children and their parents, from reading your book?

MR: For one thing, the next time they see a mother walking down the street with an autistic child—or any disabled child, I would like people to realize that the woman and her child exist as individuals, apart from their identification with a particular disability. The individuality of these children, and their mothers, is as varied as the individuality of everybody else. While they might have more than their fair share of sorrows, they also have their own joys as well. And while their triumphs would not seem to be triumphs at all to the outside world, they experience these triumphs with the full dollop of joy that any mother feels when her child succeeds in something—most likely for these mothers, who put such tremendous efforts into getting children to take a step with a walker, for example, or to learn the difference between “I” and “you,” or to look them in the eye, their sense of triumph is in certain respects even greater.

YZM: What’s next on your literary horizon?

MR: I was working on a literary thriller [before] Joe Olshan called me a year ago to tell me that Delphinium was going to publish what I eventually called Queen for a Day. I was having a lot of fun writing that, and I’m looking forward to going back to it.