Tag : israel

January 26, 2021 by admin

Social Justice Strategies •

Longtime activists Rabbis Susan Talve of St. Louis, Missouri, and Ariel Stone, of Portland,

Oregon, talk about strategies for social justice work, which, they emphasize, is a

marathon, a movement, and not a sprint. Citing Moses, who led the people of Israel out of Egypt, Talve says movements are messy and full of challenges. Take measures to be safe, bring a buddy, be an ally, show up and hold space for others, consider your different roles as individual clergy and as a congregational leader. The two rabbis’ conversation, held in anticipation of the aftermath of the 2020 U.S. election and the social justice work they anticipate will be needed, was recorded by T’ruah, the Rabbinic Call for Human Rights.

facebook.com/TruahRabbis/videos/418564815955307

- No Comments

December 15, 2020 by Polina Kroik

The Sufgania That Made Me Feel At Home In a Place That Rarely Felt Like One

In pre-pandemic years, when Hanukkah drew close, I’d find myself wandering the streets of New York in search of the perfect sufgania. I’d walk down to Breads Bakery in Union Square and order one of each kind, jelly-filled, plain, chocolate covered, then furtively bite into them on the way to the subway. The next day I’d travel all the way to the Lower East Side and get half a dozen, neatly arranged in a white cardboard box. This time I’d patiently wait until I got home, and slowly consume one in my overheated kitchen, hoping perhaps that the familiar setting would also infuse the fried pastry with a taste of the past.

- No Comments

October 23, 2020 by admin

Informed Engagement •

Encounter, a nonprofit educational organization, seeks to grow the Jewish community’s capacity to contribute to a durable resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in which all parties live with respect, recognition, and rights. It invites Jewish leaders to expand their view of this conflict and to be a positive force for communal change. You can access a library of articles, videos, podcasts and other media by staff and past participants that encourage a deeper understanding of the conflict from a range of perspectives.

- No Comments

July 27, 2020 by admin

A Mirage of Hope for Israelis and Palestinians

NAOMI ZEVELOFF covers religion, politics, and conflict, and is the former Middle East correspondent of the Forward.

In March, as coronavirus began to spread through Israel and the Palestinian Territories, I went to Jerusalem’s Old City to cover a story for Public Radio International’s The World about how people of faith were coping with restrictions on holy sites. On a timeworn stone path, I met Fathi Jabari, a Palestinian shopkeeper. He told me that he was struck by the fact that the virus makes no distinctions between people—Muslims, Christians, or Jews. “This coronavirus makes the world as a small village.”

It was an oddly hopeful message, in what was an oddly hopeful time. Among Israelis and Palestinians, I sensed a quiet acknowledgment that—at least when it comes to health—their fate is tied together. Israeli doctors trained with Palestinian ones, and some leaders even talked about cooperation.

As Israel has lifted its coronavirus lockdown, that talk has sadly diminished. Israel is pushing to annex large parts of the West Bank, where Palestinians want a state. Violence is percolating again. Recently, the Israeli army killed a Palestinian man who tried to run over Israeli soldiers in his car. The next day, Israeli police shot an unarmed autistic Palestinian man—an echo of the George Floyd killing—not far from Jabari’s store. Jabari had been right: the coronavirus turned the world into a small village. But it wasn’t enough to keep the village from fraying apart.

- No Comments

July 27, 2020 by admin

Women in the Shadow of Corona •

Times of crisis may deepen existing gender inequality and disproportionately affect women as compared to men. Data from the Israel National Insurance Institute (parallel to the U.S. Social Security Administration) illustrates that their status in the labor market is considered lower than men’s—women earn less, work more in part-time jobs and in sectors that lack job security—and they are the first to lose their jobs. At the same time they carry an increased burden of caring for children, adults and other dependents when state care and educational institutions are closed. “The Covid-19 Crisis,” a report from the Israel Women’s Network, tells how some international organizations have issued warnings along with policy guidelines on including gender perspectives in crisis management. “The crisis has two sides: a potential to erode hard-won achievements to women’s rights, but also an opportunity to use gender equality as an engine for strengthening the entire society.” iwn.org.il

- No Comments

July 27, 2020 by admin

Operation Moses Plus 30 •

Film director and producer Orly Malessa immigrated to Israel as a child with her family and about 8,000 other Jews from Ethiopia in the 1984 rescue known as “Operation Moses.” Thirty years later she searched through a huge archive of amazing photos taken by Beit Hatfutsot photographer Dan Bacher and used social media to locate individuals in the photos to interview them. She filmed them telling their reflections on making their way to a new country including joyful milestones as well as painful losses.

bh.org.il/event/operation-moses-30-years

- No Comments

July 27, 2020 by admin

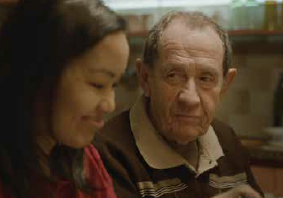

See New Israeli Film Shorts •

The Gesher Multicultural Film Fund is the leading fund supporting independent short films produced in Israel as well as the best graduation films made in Israeli film schools. During these stay-at-home times, they are sharing a wide selection of short films by emerging filmmakers they have supported over the years. “The Caregiver” a film by Ruti Pri-Bar, is about an Indian male caregiver whose employer— an elderly Israeli man— replaces him with a woman. “The Youngest,” by Rachel Elizur, is about an ultra-Orthodox widow unwilling to let her daughter accept a marital match. “Offspring,” directed by Shirly Sasson-Ezer and Dana KeidarLevin is about a woman struggling to get pregnant who is dragged to a circumcision by her superstitious Bukharan grandmother. tportmarket.com/partners/gesher-vod

- No Comments

April 20, 2020 by admin

Israel’s Women on the Margins

With Israel’s political woes blanketing the news these days, it’s hard to remember

how multi-layered and complex a country it is. Its modern society was created by socialist pioneers, who struggled, somewhat successfully, to create economic and gender-egalitarian new communities. After statehood, Israel took in Jews from Arab lands and tried to integrate them, less successfully, into that developing society. More recently, Israel’s latest challenge has been absorbing hundreds of thousands of Russian immigrants with minimal, if any ties to Judaism or Jewish life. Three new academic books written and compiled by feminist Israeli academics address these particular facets of the challenges and shortcomings of the Jewish state.

When the State Winks: The Performance of Jewish Conversion in Israel, by Michal Kravel-Tovi. (Columbia University Press, $65) is a detailed ethnography. Anthropologist Michal Kravel-Tovi focuses on how and why Israel’s state bureaucracy is involved in managing the religious conversion of immigrants (mostly young women) from the former Soviet Union (FSU), mostly women because under traditional Jewish law the religion of the mother determines her child’s religion.

Kravel-Tovi engaged in three years of research from 2004–2007, during which she sat in on conversion classes, rabbinic conversion court proceedings, and ritual immersions in a mikveh. She interviewed teachers, rabbis, judges, and women who were in the process of converting through Israel’s state-sponsored Orthodox system.

Kravel-Tovi begins by describing how and why Jewish conversion has become part of what she terms “Zionist biopolitical policy” in Israel—using conversion of former FSU women to increase Israel’s Jewish population. Her focus is how the conversion candidates and the state agents—the conversion educators rabbinic court judge—handle the contradictory forces of Israel’s conversion policy. All parties, she argues, are concerned with issues of role-play, sincerity, and suspicion, demonstrating how all parties collaborate to put on believable conversion “performances.” The final chapter features the personal narratives of the conversion candidates, who must present personal statements to the rabbinic court that lend sincerity to their conversion process.

Many of the female potential converts have paradoxical Israeli-Jewish identities. While not considered Jewish according to Orthodox halacha, many grew up in Israel believing they were Jewish (and came to Israel under the Law of Return because of Jewish family connections). Invited to immigrate by the State of Israel, but then excluded from full membership in Israeli Jewish civic and religious life, most of the former FSU women find themselves in a painful no-woman’s-land labeled the harsh exclusionary Hebrew term goya (non-Jew/gentile) in Israeli society until they convert. One senior rabbi in the rabbinic conversion court compared these non-Jewish women in Israel to landmines: “…The foreign women will marry and have children, loyal citizens of Israel. It is a commandment to clear away such mines.”

In Concrete Boxes: Mizrahi Women on Israel’s Periphery (Wayne State University Press, $36) feminist anthropologist Pnina Motzafi-Haller of Ben Gurion University documents the lives of five Mizrahi women from the economically struggling development town of Yerucham, in Israel’s Negev. An activist who lived in the U.S. for almost two decades before returning to Israel, Motzafi-Haller published the Hebrew version of this book in 2012, as she wanted it to be read and discussed within Israel. The book was adapted into a play produced by the Dimona Theater, which traveled with the production around Israel for two years, dramatizing for an even wider audience the issues in Mizrahi women’s lives.

The five women featured in the book all have different approaches for dealing with the “concrete boxes” that have trapped them in Yerucham. Nurit is a single mother on welfare whose former husband was addicted to drugs; she worked many jobs to support her family. Nurit maintains dignity and finds meaning in her life through family events such as her son’s bar mitzvah. Efrat, another mother, becomes increasingly religiously observant as a way to deal with her life’s challenges. Her increased religiosity opens up opportunities for economic mobility and respectability, including a better job in a middle-class community, more than a secular education provides.

Rachel is considered a successful Yerucham resident despite her challenging background—coming from a poor family, married as a teen before finishing high school, having four children and then divorcing her abusive husband. She moves between middle-class and working-class settings, often as a representative of her community, but she is limited in her ability to juggle the different cultural nuances each group demands. Esti, “the rebel,” goes against communal norms by refusing to marry, have children or keep a job. While choosing a non-traditional path for a Mizrahi woman is freeing for her, it also leads to isolation and economic hardship. Gila, the author’s neighbor in Sde Boker grew up in Yerucham, but was able to leave her birthplace and create a middle-class, educated, professional life after leaving.

Sylvie Fogiel-Bijaoui and Rachel Sharaby have edited Dynamics of Gender Borders: Women in Israel’s Cooperative Settlements (Walter de Gruyter GmbH, & Hebrew University Magnes Press, $115)

Israel’s signature collective settlements, kibbutzim and moshavim, were based on ideals of gender equality and that of a new, egalitarian, socialist society in a new land. Kibbutzim were characterized by the communal features of formerly private domestic spaces—children’s houses, and communal kitchens, dining rooms and laundry. Moshavim were socialist agricultural communities that combined elements of individual and collective living, based on family farms. Yet, as the studies in this edited collection, show despite innovations in child-rearing practices, religious life, and labor, for women in these utopian communities, gender equality was still elusive.

The first section of the book collects women’s experiences in the pre-State period, including unique research on kibbutz mothers who wrote in secret diaries of their pain at being separated from their children raised collectively in children’s houses, pain they had to hide for fear of being seen as opposed to gender equality and the new society they were building. Another chapter explores mothers on moshavim who felt compelled to break gender constraints and fight against fascism by enlisting in British forces in the Middle East during World War II. They write of their pride in serving, but also of the sacrifice to their families and communities. On religious kibbutzim, women grew frustrated as rabbis debated whether they were allowed to wear shorts or pants while doing agricultural work, exemplifying the conflict between traditional constraints and the new, collectivist kibbutz.

In the book’s second section, we get a closer view of the period after the founding of the State. Various factors—the declining status of the labor settlement movement; the waves of immigrants from Asia, North Africa and Europe that presented many absorption challenges to Israel and the collective settlements; and Israel’s integration into the global neo-liberal economy and the processes of privatization—led to valuing individualism in the kibbutzim and moshavim. Changes arrived, but not gender equality. Articles describe how Mizrahi women immigrants integrated into moshavim, how economic and labor changes to kibbutzim and moshavim in modern times affected women, and how second-generation kibbutz mothers, rebelling against their experiences as children, pushed to make kibbutzim more family-oriented, by pressing for such “radical” changes as family meals and family sleeping arrangements.

All these books deal with people who have been on the margins of Israeli society. Together, they paint a devastating but important picture of the ways reality in Israel has failed to live up to ideals.

Susan Sapiro is a researcher and writer for nonprofits, and a book critic.

- No Comments

April 20, 2020 by admin

Displacement, Migration, Personal and Geopolitical •

In her solo show “Strangeness,” multi-media artist and actress Raida Adon explores human migration via a 33-minute video of the same name presenting simultaneous narratives of a group’s progress on foot interspersed with scenes of the artist herself in surreal situations. Exploring the emotions within the struggle to find a home, she restructures polarized stories reflecting her own complex identity as both an Israeli and a Palestinian. Born in November 1972 in Acre, Israel, to a Jewish father and a Muslim mother, Adon in her work examines her own complex biography, conflicted nations, and the relationship between two interrelated societies. Adon drew inspiration for Strangeness from footage of Palestinians in the aftermath of the 1948 War of Independence, and from pictures of the deportation of the Jews from Jaffa in 1917 by the Ottoman Empire, intertwining these collective experiences in a commentary on time and history. Complementing the film, are 12 drawings by the artist used to prepare for the video work, as well as a suitcase Adon constructed to look like her childhood home. At the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

www.imj.org.il/en/exhibitions/raida-adonstrangeness

- No Comments

March 10, 2020 by admin

What Purim in Israel Taught me About Inequality

When I was growing up in Israel I never looked forward to Purim. Pestering my overworked mother for a costume was bad enough, but the ritual I dreaded most was the mishloah manot—an exchange of baskets of candy and dried fruit. Wrapped in tinted cellophane and displayed on the teacher’s desk, these baskets let everyone know just how rich or poor we were. When the teacher redistributed the packets, everyone hoped to get the treasure troves that the well-to-do Ashkenazi kids brought. As for the rest of us, the immigrants and the Mizrahis, we braced ourselves for the grunts of disappointed and muttered insults with which our offerings would be received.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...