Tag : Hollywood

April 20, 2020 by admin

A Networker— Before Networks

Before LinkedIn, before social networking, before the word “networking” was even coined, there was Salka Viertel.

The German emigre who arrived in California in 1928 not only fashioned her “room of one’s own” to become a successful screenwriter during Hollywood’s Golden Age, she famously made room in her life and home for an astonishing roster of fellow Mitteleuropean emigre artists. Mostly Jewish like Salka, they arrived in California as refugees from fascism.

She was the refuge.

On any Sunday afternoon at Salka’s home in Santa Monica, you might share

a home-baked apfel kuchen with Billy Wilder, Igor Stravinsky, Thomas Mann,

William Wyler, Marlene Dietrich, Bertolt Brecht, Charlie Chaplin, Harpo Marx,

Arnold Schoenberg and Christopher Isherwood, who for a time lived above

the garage.

Greta Garbo, although she was Salka’s devoted friend (and putative lover) and

insisted on including Salka as a screenwriter on most of her films, naturally did not make

an appearance at these gatherings.

The social networking at Salka’s was the matrix for friendships, collaborations,

and ventures that would give rise to the Hollywood of the twentieth century.

Salka did more than open her heart and hearth to the refugees. She helped many of them emigrate to America, gathering documents, convincing others to do the same, and supporting the European Film Fund that financed their survival. At the same time, she worked hard, writing screenplays, to support her family, including her estranged husband and three sons, her much younger (by 22 years) live-in lover, and her aged mother.

“But being Lady Bountiful had its costs,” writes her biographer Donna Rifkind. “Stretched between [her young lover] Gottfried, her children, and the legions that depended on her, Salka couldn’t possibly please them all.”

The extraordinary life of Salka Viertel, aptly titled The Sun and Her Stars: Salka Viertel and Hitler’s Exiles in the Golden Age of Hollywood, (Other Press, $30) is illuminated in this thoroughly researched and generous new biography by Rifkind, an award-winning reviewer whose work has been published frequently in The New York Times Book Review.

Her tone is admiring and affectionate, but also aggrieved. “A woman, finding good

fortune in a foreign land, comforted and fed and housed the survivors of an overseas

genocide. In her old age, when her fortune was gone, only a few family members and

friends remained to feed and comfort her, and to remember her after her death…what

does it say about our values that we have chosen to dismiss so large and estimable a

life as Salka Viertel’s?”

She has not only been dismissed. She has also been dissed. “When they have

bothered to mention her at all, writers about the era have described her variously as a gossipmonger, a moneygrubber, a vengeful lesbian, an incompetent fraud and a horrible witch. (That last from a letter Kurt Weill wrote to his wife Lotte Lenya…) Some of her famous friends, including Bertolt Brecht and Charlie Chaplin, did mention her positively in their memoirs, observes Rifkind; they noted “the excellent coffee and cake she served them.”

Rifkind attributes the neglect and malevolence to jealousy, but mainly

to the misogyny that was pervasive in Hollywood (and still is) compounded by

Salka’s strong, confident personality and the influence she wielded.

Salka, referred to in the book by her first name, was unique. But she was one of

many women working behind the scenes in Hollywood.

Irving Thalberg’s Metro (later MGM) studio was “teeming with women,” notes

Rifkind, “mostly unheralded.

“Women writers…were obedient and discreet. They had been raised to expect

much less than men did—less money, less credit, less respect.”

Meanwhile, women were highly valued for their sexuality, especially homosexuality: “Hollywood was happy to impersonate Berlin’s lesbian-chic culture as long as it brought a profit.”

Rifkind’s writing throughout is detailed and evocative, with unexpected

delights. About Salka’s arrival in America, she writes, “Though she did not know it

yet, she had been translated….” Rifkind is as adept at making vivid the`scents and

sounds of Salka’s beloved Santa Monica garden—the jasmine and eucalyptus and trills of mockingbirds—as she is at delineating the indignities of Salka’s old age. “Daily she was plagued by her poverty… fearing that she would not be able to pay her medical bills.”

She had moved to Switzerland to be near her son Peter and adored granddaughter, Christine, but was distraught at having to ask Peter (married to actress Deborah Kerr) for money. She hoped that a memoir might bring in some funds. It was rejected by several publishers, and she was advised to delete references to childbirth and menopause.

Salka was 79 in 1969, when The Kindness of Strangers was finally published. Rifkind

writes that its importance lies in how, “Through her experience as a woman,

an immigrant and a Jew, she charted Hollywood’s role on the twentieth-century world stage”…and “showed that women’s influence in the picture business was not limited to that of movie stars.”

Salka Viertel died in 1978 in Klosters. Donna Rifkind has brought her to life.

Judy Gerstel is a freelance journalist, formerly a critic and editor at the Detroit Free Press and Toronto Star.

- No Comments

May 21, 2019 by Sharrona Pearl

Mel Gibson’s ‘Rothchild’ Film Ditches the ‘S’ But Keeps the Anti-Semitism

As the endless reboots, remakes, and superhero movies show, no Hollywood exec is seriously asking if we need another movie about a given topic. Movies aren’t about need. They are about want. Desire. Wish fulfillment and fantasy. Movies are where we go to imagine other worlds, and be transported from ours.

So what does it say about our world that Hollywood has greenlit a major film that uses an almost identical name to Rothschild, a name almost synonymous with anti-Semitic tropes? Whose subject is a wealthy and corrupt family who will stop at nothing in pursuit of the almighty dollar? What does it say that the film stars one of the most notoriously anti-Semitic actors of our time—you know, who I mean? If you’re not aware, google Mel Gibson and his vile comments.

- No Comments

January 10, 2019 by admin

Tough Women in Tinseltown

“There’s a French saying, an actor is less than a man and an actress is more than a woman. Men weather better. But women owned Hollywood for 20 years, and we must not be bitter.” Bette Davis to Mel Gussow, March 1997.

So opens Nobody’s Girl Friday: The Women Who Ran Hollywood—a study that seeks to right an injustice of record. Historian J.E. Smyth, has dedicated her academic career to the intricate histories of American cinema, and found a dearth of knowledge in published accounts of the women working in lm during one of Hollywood’s most studied eras, from the 1920s to the 1960s. Contrary to one what might assume given the ever-darkening gender politics of our modern Tinseltown, Smyth argues that sexism didn’t overrule the studio era of the so-called Golden Age of Hollywood, when women worked in a variety of roles in the film industry. Their names were listed on rosters and phone books alongside their male peers and their knowledge valued at the tables of powerful executives. Nobody’s Girl Friday is a deep dive into a world both wholly familiar and totally alien. We know some of the names—actresses who have become synonymous with the era in which they worked, their monikers shorthand for movie magic. Smyth opens the door for readers to see the female editors, screenwriters, secretaries and stars as a cohesive group that built the modern lm industry.

Smyth’s writing comes to us at a time when Hollywood is at something of a crossroads. The digital age has transformed the distribution field, with more and more original content coming from somewhere outside that fabled block of studios in California. The bursting dam of 2017’s iteration of the #MeToo movement, beginning with Weinstein’s ousting from one of the largest film studios in the world, pushed the women of the industry into two categories: either possible victims (of one degree or another) or possible enablers.

The #MeToo movement, beginning with Weinstein’s ousting from one of the largest film studios, pushed the women of the industry into two categories: victims or enablers.

Nobody’s Girl Friday acknowledges from its outset that the Golden Era of Hollywood was time-limited—indeed, that quote by Bette Davis that opens the text speaks in past tense. There is an expectation that readers have familiarity with the various studios in operation at the time, some of their more famous executives, and the films they produced. Perhaps surprisingly to readers who associate Hollywood with Jewish creative work, Smyth does not portray the film industry as especially Jewish. The women she profiles at length are multifaceted—so much so that they could hardly be reduced to tokenization. Smyth cares deeply for her subject matter, and that attention to detail shines through in every page of what is, above all else, a study in adoration. In that sense, it feels less vitally important that the book be accessible as an entry-level text for the casual reader—something that could be flagged as a potential shortcoming.

The introduction in particular is a tough way to begin: readers are launched headlong into paragraphs listing names of hundreds of women working in Hollywood during the era, without contextualization. This attempt to atone for decades of erasure is admirable, but readers run the risk of scanning the page and seeing the roster fly by like credits at the end of a film. Her fleshed-out biographical chapters are far more engrossing.

Nobody’s Girl Friday is, on the whole, an excellent historical companion for those who have taken a few lm studies classes. Her points are well taken: the Golden Age of Hollywood was golden for more than a few reasons.

Justine Orlovsky-Schnitzler is a writer and Lilith contributor on the move, currently based in Arizona.

- No Comments

May 23, 2018 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

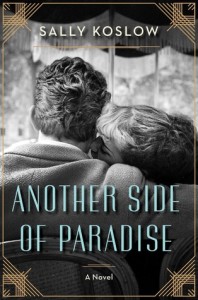

A Novel Imagines F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Lesser-Known (and Jewish) Love Affair

In 1937 Hollywood, gossip columnist Sheilah Graham’s star is on the rise—while literary wonder boy F. Scott Fitzgerald’s career is slowly drowning in booze. But the once-famous author, desperate to make money penning scripts for the silver screen, is charismatic enough to attract the gorgeous Miss Graham, a woman who exposes the secrets of others while carefully guarding her own. Like Fitzgerald’s hero Jay Gatsby, Graham has meticulously constructed a life far removed from the poverty of her childhood in London’s slums. And like Gatsby, the onetime guttersnipe learned early how to use her charms to become a hardworking success; she is feted and feared by both the movie studios and their luminaries.

A notorious drunk famously married to the doomed Zelda, Fitzgerald fell hard for his “Shielah” (he never learned to spell her name), who would stay with him and help revive his career until his tragic death three years later.

Working from Sheilah’s memoirs, interviews, and letters, Sally Koslow revisits their scandalous love affair and Graham’s dramatic transformation in London in her new novel, Another Side of Paradise, out this month from HarperCollins.

Koslow, the former editor-in-chief of McCall’s Magazine and author of four other novels, including acclaimed international bestseller The Late, Lamented Molly Marx, talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about how she came to uncover the secrets of Graham’s past—and why.

- 2 Comments

April 12, 2018 by admin

My Summer in Hollywood

“Truth even unto its innermost parts.”

—BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY MOTTO

I was a student at Brandeis University when Anita Hill gave her groundbreaking testimony to the Senate Judiciary Committee in the fall of 1991. This single courageous act sparked a national decades-long conversation on sexual harassment in the workplace, a conversation which, with allegations of abusive behavior by Harvey Weinstein and now countless others, has exploded in a seemingly end-less stream of #MeToo narratives.

Me, too.

My original career ambition was film-making. While at Brandeis, I started a film club on campus. I collected signatures, petitioning the administration to establish a film studies program. As the student liaison, I met with the provost, who shared a similar vision. He put the wheels in motion, and he also contacted a Brandeis alumnus, a director in Hollywood, who offered me an intern-ship for the summer as his assistant. I was over the moon!

Once in Los Angeles, though, I felt like an East Coast fish out of water. At 20, I was the youngest adult on set. I wanted to make a good impression, to be taken seriously, but there was not a lot for me to do. I spent a lot of time “gophering” and observing. As an unpaid intern, nobody seemed to mind, particularly not the famous lead actor; then in his mid-40s.

Each day, the actor would direct sexual comments at me. My surname was then Inspector. “Inspect-her? I don’t even know her!” was his favorite. It seemed that, to him, my role was to be his personal pre-performance-mojo-maker. I felt exposed, yet invis-ible. Humiliated, I lacked the words or self-possession to stop him. My only reprieve came when his wife was on set.

I had hopes that the director would intervene, but he didn’t. Maybe because he was getting the performance he needed, he turned a blind eye.

And then, one Friday, the director invited me to his home in Beverly Hills for a Saturday barbecue and a swim with his family, saying another cast member would be coming. I knew hardly anyone in L.A., and meeting the director’s family sounded appealing, so I took two city buses and then walked to his house.

When he opened the door, I was surprised to find I was the only one there. Everyone else had “other plans.” His wife and kids were on vacation. We chatted awkwardly for a short while then he nonchalantly suggested that we go into the pool. I felt slightly queasy. My intuition flashed a small red flag, but I told myself it is fine, this man is my father’s age, and he was from Brandeis, after all! And he has never acted inappropriately with me at the studio.

Saying no to the pool felt just as uncomfortable as saying yes.

In the water, the director lunged at me, put his hands around me, and tried to kiss me. I pulled away and said a firm no. He backed away sheepishly. I was stunned, confused, and crushed. I don’t remember getting out of the pool, or any further conversations, or leaving his house. I don’t remember if I he drove me home or if I took the bus. I just remember, vividly, my shock and sense of betrayal.

Monday, back on set, we both pretended that nothing had happened. I continued to endure the lead actor’s taunting. I finished the internship, flew back East, and decided never to work in the industry again.

The following year, I confided in the teaching assistant in my Women’s Studies class, a graduate student who was kind and with whom I felt safe. She encouraged me to report the pool incident to the provost. I thought she was crazy. Who would believe me? Who would find fault with this “distinguished alum.” I knew that he’d misused his power, violated an unspoken trust, but I also felt ashamed, and blamed myself. Was it my naiveté that let this happen? Was it my hope to ingratiate that let the boundaries slide? Embarrassment eclipsed my anger, and it was years before I spoke about the episode again. Even a friend to whom I spoke about this experience years later asked, “What were you wearing? Did you have a bathing suit?”

Almost 20 years later, in 2009, the Film, TV, and Interactive Media Program became a reality at Brandeis.

I never did become a filmmaker, though when I was a senior facing graduation, the pressure of finding gainful employment caused me to waver in my decision to avoid the film world. I contacted the director, and he offered me a job at the Hollywood studio, a position much coveted by my film-aspiring peers at Brandeis. Perhaps I should have accepted the job and learned to navigate the precarious waters of Hollywood. But fearing its reputed quid-pro-quo culture (who slept with whom to get where they were), I never called him back. Instead, I spent the next two years shuffling together part-time work in a bookstore, a restaurant and a glass blower’s shop, feeling befuddled about my future.

Much of my youthful energy, and many college credits, had been spent on my filmmaking aspirations. As I crossed the threshold into the “real world,” I felt the typical soup of emotions—anticipation, trepidation, enthusiasm—but also defeat, knowing that my goal had gone off the rails before I even got it moving.

Decades passed before that long-ago internship experience resurfaced. It was 2012 when some midlife self-reflection unearthed from memory my summer in Hollywood. Anita Hill had joined the Brandeis faculty in 1998, and I sought closure by writing to her, giving my own “testimony” of sorts. Professor Hill graciously replied, saying that her basement is filled with thousands of such letters and that she keeps them all filed neatly. She asked me if she could share my letter with her students, to help “validate their own feelings and give them hope.”

Monday, back on set, we both pretended that nothing had happened. I finished the internship, flew back East, and decided never to work in the industry again.

I thought then that I’d found the resolution I was looking for. But a couple of months ago, reading the scores of accounts by women and men about the widespread tolerance of the culture of harassment and abuse of power in Hollywood and beyond, I began reflecting again. In those other women’s stories I could see the complexity of my own experience. Like many of them, I had internalized the warped cultural message that it was my own fault. In their honesty, I am now finding my own truth.

I eventually did find a new passion, a career in homeopathic medicine. I took comfort in the “earthy-crunchy” nature of homeopathy, diametrically opposed to the glitzy, superficial culture of Hollywood. Surely a profession as altruistic as natural remedy healing would be immune to the behavior I found in Hollywood. (Unfortunately, my naiveté accompanied me to my new career, and I soon found out that sexual harassment does indeed cross the boundaries of humanitarianism. But that’s another story.)

Until now, I have wanted to give the director, my Brandeis kinsman, the benefit of the doubt. Perhaps his family had made last minute plans. Perhaps I was the only one. Some people to whom I’ve recently revealed my experience have suggested I should feel fortunate “Well, at least he backed off, he didn’t rape you.” True, he was not the monster that Harvey Weinstein turned out to be. However, the stories of the “Weinstein entrapment”—Come to my house, my office, my hotel room, for a surprising one-man show—sound eerily familiar.

Hearing these other stories has forced me to re-examine the details of what happened during my Hollywood summer, and how I felt. And to decide whether to say anything more about it. A quick Google search revealed that the director has gone on to have a notable, influential, and very lucrative career. My desire for truth, justice, and protection of others has seesawed with my fear of repercussions. So I still feel vulnerable.

Writing this account has felt like diving to touch the bottom of a dark pool of water, only to find the bottom so deep that I lose my breath on the way up. One thing is clear, the message that I gleaned as a young woman: The men, who are in power, are not interested in my brains, my creativity, my acumen; I am valued for what I can provide sexually. My summer internship left me feeling low and cheap, not the person I knew myself to be. And for that reason, I did not go back to Hollywood.

My daughter is now a college freshman. During Thanksgiving break, I told her about my experience, and we watched a recording of Anita Hill’s 1991 testimony. With the passion of a first-year student, my daughter exclaimed that no one should have to choose between livelihood and safety! I concurred. I explained to her that unpaid interns are particularly vulnerable, that while a handful of states have now passed laws to protect interns under state law, federal law, unfortunately, does not protect them. Human rights laws like Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 give only employees protection from workplace discrimination and harassment, not unpaid interns. She was outraged, and rightly so. She asked me if I thought that anything would have been done back then if I had reported back to the university provost. Given the times, it’s hard to say. Universities had no institutional system of reporting and recording harassment. Though the incident did not happen on campus, and the director did not work for the university, an incident such as mine could still be recorded, so that, if prior or later reports were ever made, a pattern would be revealed.

I also recently spoke to the former provost, the one who had arranged my internship, and (finally) told him what had happened back then. He was “very, very sorry to hear that [my] experience in Hollywood was not what it should have been. Very sorry.” Understanding his dismay, and concern about my well-being, I affirmed to him that he himself had had no way of knowing and, of course, had only tried to help me realize my aspiration. The experience had nothing to do with him. I felt the need to reassure him that I was ok, and that my life had turned out just fine.

Amy I. Rozen works as a classical homeopath and registered nurse at The Remedy Center in Morristown, N.J.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...