Tag : feminism

February 23, 2021 by Ilana Kurshan

Esther in a New World

As part of his only recorded direct speech in the book of Esther, Mordechai exhorts his orphaned cousin Esther to appeal to King Ahaseurus, suggesting that Queen Esther’s raison d’etre was to rise to the occasion and deliver the Jewish people from danger. And yet, as a new anthology of essays suggests, Queen Esther has served many purposes over time — her inspiration and her legacy have been invoked and appropriated in contexts from colonial politics to the coronavirus vaccine clinical trials.

In Esther in America, edited by Rabbi Dr. Stuart W. Halpern (Maggid, $29.95), an array of scholars, rabbis and educators consider the various roles that Esther — and the scroll in which she appears — have played throughout American political and cultural history, making the case that this ancient Persian story of Jewish triumph over evil resonates with many aspects of the American experience.

The popular and prolific Puritan minister Cotton Mather frequently cited Queen Esther as a model of independent action and fidelity to her husband in his Ornaments for the Daughters of Zion, a conduct and virtue manual. American abolitionist women, including Angelina Grimke, Harriet Beecher Stowe and Sojourner Truth, identified the plight of the Jews in Persia with the suffering of the American slaves, casting Esther first in the role of the Black slave woman, valued for her sexual capital, and then in the role of the Southern Christian white woman, charged to speak out against injustice. In both contexts, Esther emerges at once obedient and independent, abused and empowered.

(more…)- No Comments

February 10, 2021 by Steph Black

A Reproductive Shabbat

On a Saturday afternoon many months ago, I leaned across the center console of my car and pushed open my passenger side door to welcome in a stranger. I only knew her first name and cell phone number, and that she was having an abortion later in pregnancy.

This was my Shabbat, bringing her back and forth between one of the five clinics that would perform the procedure she needed and the modest hotel a mile away.

(more…)- No Comments

February 3, 2021 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Forget Russia: a Q&A with L. Bordetsky-Williams

“Your problem is you have a Russian soul,” Anna’s mother tells her. In 1980, Anna is a naïve college senior studying abroad in Moscow at the height of the Cold War. She’s also a second-generation Russian Jew raised on a calamitous family history of abandonment, Czarist-era pogroms, and Soviet-style terror.

Novelist L. Bordetsky-Williams talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about how Anna’s experience both illuminates the dark corners of her family’s past and shines a light toward the future she is fashioning for herself.

YZM: You write about Russia with such affection and intimacy; what is your relationship to the country?

(more…)- No Comments

January 27, 2021 by Sarah M. Seltzer

My Anger at the Kavanaugh Hearings Inspired Me to Take Action

Two years ago, I was walking on the street during the Kavanaugh hearings and noticed that almost every woman I walked by was glued to her phone; their faces reflected my disgust and my fear for the future. The brutality of the hearings, the callous dismissal of Christine Blasey Ford’s accusations, the general smugness of Justice Kavanaugh and his elected supporters knocked me back in a visceral way. I finally snapped.

I needed to channel that frustration and anger into something productive, so I decided to combine that post-Kavanaugh fury with nearly 20 years of work in reproductive health and develop a program to improve access to birth control in rural and underserved communities.

I went down a rabbit hole of research on models for improving access to such care, and found that in rural communities around the world, mobile clinics are a proven means of delivering care directly to healthcare deserts.

Next, I needed the where.

In 2018, four states—Mississippi, Louisiana, South Dakota, and North Dakota—had “trigger laws,” meaning that if Roe v. Wade is overturned, abortion immediately becomes illegal. More states have since joined them in passing similar legislation. Among them, Mississippi has some of the poorest reproductive health and sexual health outcomes in the nation. In the Mississippi Delta, one of the most rural areas in the state, 62% of pregnancies are unintended and publicly funded clinics are unable to meet 60% of women’s needs for reproductive health care. I reached out to institutions and organizations to understand if what seemed like a good idea in my head—using mobile clinics to increase access to care effectively in birth control deserts like the Delta—would work in the reality of rural Mississippi. I quickly found a community of allies passionate about reproductive health care eager to help launch a new local program in an area where the existing infrastructure is unable to meet the overwhelming need for care.

Two days after Justice Kavanaugh was confirmed, I founded Plan A.

Patients living in rural areas are less likely to receive reproductive health care than their urban counterparts. The nation’s healthcare disparities are particularly stark for women of color. Residents of some small towns are forced to travel far distances for healthcare with few or no public transportation options; telehealth is often unavailable due to poor broadband access. Care is prohibitively expensive for the uninsured, or for those unable to afford their deductibles. The legacy of racial and economic injustice in the healthcare system creates additional barriers to care.

For all these reasons, for the past two years Plan A has focused on residents in the Mississippi Delta. Our conversations with local organizations and community members brought us from an idea into a fully formed organization rooted in the priorities and needs of the community we serve. We are opening our first mobile clinic early next year, expanding services beyond my original plan: the mobile clinic will now offer free birth control from condoms to long-acting reversible contraception, STD and HIV testing, PrEP HIV prevention, and primary-care screening blood pressure, diabetes, cholesterol, depression, and more to uninsured and underinsured residents. And we have plans to expand this program to other high-need areas in the future.

Political change and advocacy often feel like a devastating game of one step forward, two steps back.

Working on issues constantly on the precipice—healthcare, social justice, climate change, education—is emotionally and physically draining. When I founded Plan A, I was driven by what a friend called “divine feminine fury.” Unfortunately, that fury is constantly being replenished, although my anger is coupled with excitement for the impact Plan A’s clinic will have on improving access to care.

The Amy Coney Barrett hearings set off more shockwaves of fear and uncertainty for the future. While politicians litigate the right to reproductive health, women throughout the country face insurmountable barriers to getting birth control. As we rally behind radical change and lobby the new administration, programs like ours will provide essential services to people left out of the conversation. I’m inspired by the momentum created by tangible victories from movements and organizations like Plan A across the country that are improving lives despite the policies crafted to destroy them.

Caroline Weinberg, MD, MPH, is the founder of Plan A Health.

- No Comments

January 26, 2021 by Eleanor J. Bader

Honoring the Memory of a Special Young Woman— by Teaching Consent

When Erin Michele Levitas was 19, she was raped by someone she knew. As she processed and healed from what had happened, she made a decision: After college, she would attend law school and become an advocate for survivors of sexual assault.

(more…)- No Comments

January 26, 2021 by Sarah M. Seltzer

Camera Ready

For six decades, photographer Joan Roth has photographed Jewish women around the world, and made her mark as a street photographer, ethnographer, portraitist and photojournalist, capturing civil rights and feminist events, political rallies and the International Women’s Conferences in Nairobi and Beijing. Her photos are exhibited internationally in museums and galleries, published in two important books and showcased in magazines (including this one, where she is the longtime staff photographer). Her soulful photos tell stories alive to the moment.

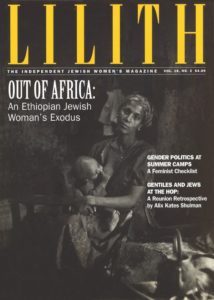

Some of her images are iconic: Bel Kaufman in front of a photo of her grandfather Sholom Aleichem who holds Bel as a child on his knee; the unmistakable Bella Abzug photographed from behind; an Ethiopian woman, Abeba Brehan, completely poised as she looks into the camera while nursing her child; the Belz Rebbetzin dancing in Israel with her daughter-in-law, their eyes closed as if in prayer.

And she has lifted up her subjects: A woman of extraordinary empathy, she was the first photographer to bring attention to New York City’s growing and diverse population of homeless women in the 1970s, capturing their plight with dignity. The work didn’t end with her revealing and compassionate images. Roth got to know the people who carried their lives in bulging shopping bags. She brought them coffee and clean clothes and took up their cause, advocating with city officials for their rights to safe shelter.

“Photography has enabled me to go beyond myself, to enter the lives of people I would not have been able to meet otherwise, to know people in a deep way,” she says in an interview. “They continue to enhance my life.”

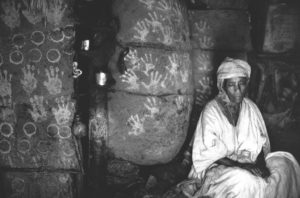

Sarah Afota, clairvoyant and healer. Casablanca, Morocco, 1991.

At 78, she’s still running with the pack of street photographers in the margins of protests, able to get herself to the front of the crowd or wherever she needs to be (she admits that her younger colleagues let her push ahead of them these days). She says she usually dresses in all black so that she’s unseen, but it’s hard not to notice the petite woman darting through crowds. In her signature big round black eyeglasses and her waves of silver hair, she’s an elfin presence. The very day after the November presidential election, during the pandemic, she was seen–mask on, Leica in hand, her press pass dangling around her neck—at a Count Every Vote demonstration.

As her granddaughter Shira Gorelick—herself a budding photographer, television writer and documentarian who has observed Roth in action—explains: “She appears so cute and sweet. And she’s also fierce. People don’t see it coming. She can channel all of that when she’s doing street work.”

Lately, she’s had a bit of back trouble, but when she’s taking pictures, she’s so totally immersed that she feels none of the pain.

“For my grandmother,” Gorelick says, “the camera is her sixth sense.”

Project Kesher activist Victorya and her “babushka” (grandmother) after blessing Sabbath candles for their first and only time together, Kamenets-Podolskiy, Ukraine, 2004

Irene Bell at the Lido Spa Hotel snack bar, Miami Beach, 2003

U.N. Fourth World Conference of Women, Beijing, 1995

After school busing, friendships developed, 1974

Sonia Sofia Mary Ellen Barbara and her personal treasures. NYC, 1974

This wasn’t the life Roth intended to have when she was growing up in suburban Detroit, and she’s grateful for all the twists that brought her to this moment.

The youngest of three siblings, she’s the daughter of a dentist born in Ukraine who immigrated to the U.S., and a mother who grew up in Detroit. A homemaker who invented things, including the first hair curler of its kind, made of rubber and then from cork (patented), Roth’s mother kept a kosher, observant home Roth’s father attended synagogue regularly, her mother less so. “She would just lift up the window and talk to God.” Some of that same intimate spirituality rests in her daughter Joan, too.

Roth, who attended public schools and Hebrew school, recalls, “I wanted to be something. But I didn’t know what.”

She thought about going into theater, and after a year of college she moved to New York to join her boyfriend, Jac Roth, with a hope of attending the New York Academy of Dramatic Arts. She lived at the Barbizon Hotel for Women until her parents insisted that she get married or return to Detroit. At 20, she chose marriage. Her new husband, a businessman, preferred that she be at home. She was happy, she says, and gave up on her theatrical aspirations.

They had two daughters, Melanie and Alison, a home on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, and a house in the Hamptons. Then Roth attended her first women’s conscience-raising group, and the unfolding of a new life began. She recalls group members asking her why she smiled all the time, and why she didn’t “do anything.”

“I think I wanted to do something for myself. My ex-husband didn’t like that. It wasn’t in our contract,” she says.

In the early 1970s, she began working for a commercial photographer. A MoMA exhibition of photographs by Diane Arbus, and the wide emotional range of Arbus’s images, changed her life. She sought out photographer Lisette Model, whose highly valued master class in New York City Arbus had attended. Roth showed up with what she describes as a “terrible portfolio,” but Model allowed her to join. She learned important lessons of street photography from Model, as well as lessons for life.

“Never think you are so good.” “Don’t take work for money; the work will be mediocre,” Model insisted. “It’s easier to do something than to try to do something.” And, to Roth herself, who was then in her late 20s: “Wake up before you miss the rest of your life.”

She also studied with photographer and master printer Sid Kaplan, who printed for Robert Frank, Cornell Capa and others, and worked in Kaplan’s darkroom. Now a close friend, Kaplan has been printing Roth’s photos for decades.

In 1971, she and Jac Roth divorced. To help support herself and her young daughters, she sometimes photographed weddings and bar mitzvahs, but most of her work grew out of her own pursuits, twinning photography and social justice.

“I used to be afraid to go anywhere myself,” she says. “The camera is an entrée into the world.”

Accompanying the Hasidic bride to the wedding canopy, Brooklyn, 1980s

Actress Maia Morgenstern, wearing a fake arm culled from possessions of the dead, in a play about the Vilna ghetto at the Romanian National Theater, 1993

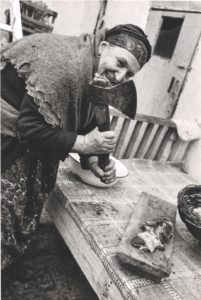

Zoli Kivono Simkevoah, the best caterer in Bukhara, 1991

Jewish women were the potters in Ethiopia, and open hands on handmade earthen storage bins symbolize blessings of the priests, 1984

Devorah, an Israeli from Chile, with timbrel, singing with women who sail down Lake Kinneret annually seeking the biblical Miriam’s Well

As she was beginning her photographic career, Roth moved her daughters from a private kindergarten (where they went to class with the daughters of Dustin Hoffman and Joel Grey) to the local public school. Then she teamed up with a close friend and others to integrate Public School 190. Her friend’s daughter is now making a film, “Bakery Days,” named for their meetings every morning at the L & H Bakery, where they planned their revolutionary work.

In the worlds she captures with her camera, Roth quickly becomes an insider. She doesn’t step out of the story. While she’s not in the picture, she’s grounded in the lives she is documenting.

The first time she met a woman with no housing was on the street across from her apartment building on the Upper East Side; before that, she’d never realized that there were women who had no homes. Sonia Sofia Mary Ellen Barbara, as she introduced herself, with her clothing held together with safety pins, was Jewish. Roth brought her food and money, and would speak to her and others who began congregating there—before the building installed spiked railings on the ledges so they couldn’t sit. With their consent, she took photographs. (Lisette Model was adamant about asking people for permission before taking their picture, a practice Roth follows.)

“I was shocked. I wanted to know who these women were, how they got here.” She admits, “I was afraid that I too might end up homeless.”

Roth probed, and learned that the city’s sole women’s shelter had only 47 beds. With a small grant, she investigated further and wrote a report on homeless women for the Manhattan Bowery Project, including her photographs. A few city officials became interested in the women’s plight, enlisting Roth as part of a new task force. Ultimately the city expanded its facilities and services for homeless women, and in 1977, Roth published some of her black-and-white photos of women who lived on the streets, along with their stories, in an article for Ms. titled, “If I’m not on my milk crate, you can find me in my phone booth.”

Her photos show the women in doorways or pushing carts filled with their belongings; a few are asleep and some smile at the photographer. A collection of those photographs appeared in Roth’s 1982 book, The Shopping Bag Ladies of New York and some, which open up these women’s worlds to viewers who had previously looked away, are in the permanent collections of the Brooklyn Museum and the Museum of the City of New-York.

Harriet Lyons, one of the original editors of Ms., who worked closely with Roth, explains, “Joan had a very personal connection to this population. She was definitely on the front lines, using her talents, which are prodigious as a photographer, to create awareness and support for women’s issues and expose discrimination and all the obstacles that women faced.”

Queen Mother Dr. Delois Blakely at the statue honoring her work to end homelessness, Socrates Sculpture Park, NYC, 2014.

Columbus Circle, NYC, November 7, 2020, spontaneous celebration after the U.S. presidential election was called for Joe Biden.

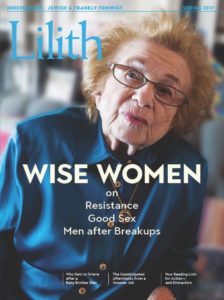

In 1978, Roth began her work for Lilith. Over the years, she has captured for Lilith’s pages Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg in her chambers, Israeli feminist pioneer Alice Shalvi, Yiddish theater grand dame Mina Bern, Dr. Ruth Westheimer, and many others who’ve appeared on Lilith’s covers.

After her divorce, Roth was drawn to Jewish life and observance again as she had been while growing up. When she discovered the Carlebach Shul, that became her spiritual home. Then, at a 1984 Shabbat dinner with friends from the congregation, someone mentioned having been on a mission to help the Jews of Ethiopia. In that moment, Roth says, she knew she would travel there, launching a 12-year odyssey in which she made more than 40 visits to document Jewish women around the world.

“Jewish women are so extraordinary. There’s no end to the extraordinariness,” she says.

She claims there’s some spark of mutual recognition when she meets another Jewish woman. The landscapes and faces in her Ethiopian photos look biblical, with one woman making an earthen jug, another dipping her pitcher into water to serve others, and an elder peeking into a synagogue, which she is not allowed to enter. A striking trio wrapped in layers of fabric hold umbrellas to protect them from the sun, a rare sign of modernity. As is Roth’s way, she later connected with many of these women in Israel, and some when they visited New York.

In the early 1980s, anthropologist Morrie Fred helped arrange a show of the Ethiopian photographs at Stockholm’s Museum of Ethnography, its first major exhibition on a Jewish subject. When Fred returned to Chicago as director of the Spertus Museum, he showed Roth’s Ethiopian work in a 1991 joint program with the DuSable Museum of African-American Art.

“The humanity of Joan, which comes through in her photographs and in the meticulous exhibition labels she wrote, is quite remarkable, and unique,” says Fred, who is now a retired professor of anthropology at the University of Chicago (and also one of Roth’s ever-expanding circle of friends who accompany her on adventures when visiting New York). The Ethiopian photos have been exhibited at The Jewish Museum in New York, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, and in Israel.

To flip through the pages of her 1995 book, Jewish Women: A World of Tradition and Change, is to be surrounded with the faces of women Roth befriended in Yemen, India, Morocco, Russia, Ukraine, Eastern Europe, Bukhara and Israel as well as Ethiopia. She captures emotion in an image and its description, like the longing of an Indian movie actor who struggles between her Jewishness and fame. The centerfold opens to a wide spread of candles, with women alone and in groups lighting, blessing, reflecting. This spectacular volume, which also inspired many exhibitions, is a tribute to Roth’s strength and vision.

Gloria Steinem has said that “Joan Roth has looked at the Jewish world as if women mattered—and therefore as if everyone mattered. Across all boundaries of geography and language, there is not only a common world of belief, but also a common world of women. We see into its intimacy through her eyes.”

Roth seems to fall in love with her subjects, even as she doesn’t like to call them subjects; she prefers to call them her teachers. They are her intimates, sisters in spirit. In Ethiopia and Yemen, she traveled without a translator. “The camera was a language between us.”

When I ask about her ability to gain the trust of the people she photographs, she says, “That’s what I do better than photography. It’s something innate,” she adds. “I really care about them. I don’t have a formula. I want to share their lives and share that with the world.”

Back in New York, friends introduced Roth to Leonard Sanders, and they married in 1998. Together, they tried to help a pair of homeless women, Maggie and Marcia, living in Central Park, and eventually helped Maggie (after Marcia left the Park with her boyfriend) move into an apartment they helped subsidize. Sanders died in 2011, after a long illness.

Roth has lived in the same apartment for more than 55 years. Her daughters, Melanie Roth Gorelick and Alison Zingale, describe life after their parents divorced and Joan pushed ahead with her photography, “giving up material interests to follow her art,” as Melanie recalls.

The family lived modestly, with the girls relying on scholarships for camp and other activities, and working after school as they got older. “Still, my mother didn’t give up on helping others,” Alison says.

Theirs was a childhood of attending women’s marches, and they’d be greeted on their way home from school by the homeless women on their block who’d ask after their mother. Years later, Maggie was a guest at Melanie’s wedding.

“I tell my children,” Melanie says, “that I didn’t get to be a doctor or lawyer. I had to be a soldier for social justice.” Melanie is now Senior Vice President of the Jewish Council for Public Affairs. Among her successes is launching anti-trafficking efforts in the Jewish community. Alison, a social worker, thinks of her mother as “a non-degreed social worker.” She says that their mother was a free spirit, always thinking out of the box. She once turned their kitchen into a darkroom, and when it went back to being a kitchen had a graffiti artist paint the walls. But kitchen or not, Joan rarely cooks, and the family relied on take-out and local diners. Many of the people in her photographs became their guests.

Shira, the oldest of Roth’s four grandchildren, sees her grandmother as mentor and friend. “She gave me a toolkit and vocabulary by which to speak about the world and about feminism,” she says. “I learned from her to follow my passion, go the extra mile and stay curious.

“She is fun and lively and engaged. She takes what needs to be taken seriously very seriously, like human dignity and issues of social justice—and can laugh at herself.”

Roth and her camera have become fixtures at certain kinds of Jewish events, such as those for the Jewish Women’s Archive, JOFA, Project Kesher, the Hadassah Brandeis Institute, “whether at galas, or doing a shoot for Lilith at a women’s march or feminist conference,” according to Lilith’s editor-in-chief, Susan Weidman Schneider.

“Her subjects always feel very special,” she continues. “From behind her camera she keeps up a steady stream of encouragement and compliments which never sound insincere. The subject believes them too: “You’re gorgeous.” “So wonderful.” “Really beautiful.”

These days, with the pandemic, Roth is at home more, spending time organizing her many thousands of photographs. Still, she can’t resist heading to a rally or protest or interesting gathering, always with her camera. Shira, who shares her grandmother’s adventurous spirit, says that they recently went to Chinatown together, a place Roth loves—she loves many things in her life with ferocity—for its busy streets, herb shops and alternative medicine practitioners.

Her advocacy continues as she helps her friend, Queen Mother Dr. Delois Blakely, a former nun known as Ambassador of Goodwill to Africa and named Community Mayor of Harlem, to avoid eviction from the home where she has lived with her disabled daughter since 1982. Queen Mother says Roth is “helping every step of the way” to fight predatory lending and mortgage fraud and help her keep her home.

“She fights injustice wherever she finds it,” says feminist philanthropist Sheri Sandler of Roth. “Her work and her life are so integrated.” Sandler, herself involved in the arts and social justice and the director of a family foundation focusing on girls’ and women’s issues, adds, “Joan is absolutely the most extraordinary friend.”

Not all of Roth’s efforts to help have been appreciated, and sometimes those she meets need more help than she is capable of providing. She says that occasionally people she encounters through her photography and advocacy get angry at her, and “the same door that opens can close.” A woman who appreciates complexities, she accepts how situations unfold.

Several people echoed Morrie Fred’s belief that Roth deserves a major museum retrospective. Confident in her work, she has often been too busy getting on with her next project to promote herself. Over the years, Jewish communal funds were granted to other photographers documenting Jewish communities, but not Roth. The lack of support disappointed her, but never stopped her.

As she explains, without bitterness, “I wasn’t a good fighter for myself in those days. I could fight for other women. I always believed in myself and I just kept going.

“I just always feel that God helps me and is there for me,” Roth says. “I hope that I’m right.”

She’s a person who hates to say goodbye to others; she doesn’t want her connections to the people she has met to end. Her timeless photographs allow her to visualize and remember all those who have landed in her big heart.

Sandee Brawarsky, an award-winning journalist and editor, is the culture editor of The Jewish Week and author of several books, most recently 212 Views of Central Park: Viewing New York City’s Jewel from Every Angle.

- No Comments

January 25, 2021 by Sarah M. Seltzer

Breaking the Taboo

I’ve been committing adultery.

Married Jewish Female with beloved but impotent husband seeks man to become friend with benefits. I am not young, beautiful, thin, or petite, but I’m still juicy and fun. Man sought is kind, literate, clean-smelling, on the chubby side, circumcised, drug- and disease-free, a nonsmoker, appalled by Trumpism, and utterly discreet. Forty-year-old virgin okay.

I never thought I’d post this personal ad. For one thing, where could it run where it wouldn’t attract responses from every creep, perv, and blackmailer within a hundred-mile radius? For another, what man with the least bit of sexual chemistry (who isn’t a creep or a perv) would want to get it on with a larger-than-life woman who, though she presents younger than her actual years, is undoubtedly of a certain age? Plus, my work life involves Jewish religious institutions, and the professional organizations to which I belong take a firm stand against violations of the Seventh Commandment.

Mine is not the only sexless marriage in the world, of course, nor does my husband deprive me of affection, support, and devotion. He’s as loving and sweet as he was the day we met, more than 35 years ago. He has made possible everything I’ve accomplished during the past two decades. We have a nice, paid-for home and adequate funds. I have work that I enjoy and that brings benefit to the community. I am fortunate and blessed. Not having sex is definitely a first-world problem, and it seems churlish to complain about it.

But I missed making love. I missed wrapping my legs around my husband’s big body as he thrust into me. I missed riding him, watching his face contort comically with pleasure. I missed the orgasms I didn’t have to produce for myself. Years past menopause, I had none of the dryness or lack of interest for which TV commercials offer solutions. In short, I was still ready to go.

It has been more than 12 years since we last had sex. My husband and I both understand that this isn’t about lack of desire, but lack of ability. He has experienced physical issues during these 12 years that, while not directly related to erectile dysfunction, probably introduced factors that helped it along. Treatment with testosterone and two different brands of boner pills was ineffective. Other interventions are painful, invasive, or both. He doesn’t want to experience them. I don’t want him to experience them.

Things were different when we were first together. We had sex again and again and again our first night together, which was also the night of our first date. Once, he was at my apartment erev Pesach, and we got horizontal 20 minutes before guests were due to arrive for seder. For many years, sex was a big part of how we expressed our love for each other.

And then it wasn’t.

Of course, there are other ways of achieving satisfaction as partners, but they aren’t happening much either. He doesn’t offer, and until recently, I wasn’t asking—in part because whatever he’s willing to do for me, I can do for myself. When all is said and done, I’m a cisgender heterosexual woman who likes good old, plain old, straight-up, train-into-the-tunnel intercourse. I’m not sheepish about it. The bod wants what it wants.

Certainly some of this angst over not having sex was unresolved rage about the aging process. I knew we wanted to grow old together, but I didn’t think old was going to happen so soon. My husband’s days now revolve around weather reports and TV reruns; he’s 66 going on 90. Meanwhile, I’ve aged too, but after double knee replacement and regular gym workouts, I’m able to transcend the aches and pains that come with advancing years, and, baruch ha-Shem, I haven’t been afflicted with any debilitating health issue. And my lady parts haven’t aged at all. I wish I’d dried up and lost interest in sex after menopause. Instead, I’m a horny 32-year-old trapped in the body of a chubby crone.

Jewish tradition doesn’t begin to address this problem. The Sages, in Tractate Ketubot 61b, state clearly that a husband is obligated to have sex with his wife and satisfy her regularly, as frequently as his occupation permits, but the Sages lived at a time when people routinely died before age 50; most husbands didn’t outlive their ability to stand and deliver. And while the Rabbis saw a husband’s failure to have sex with his wife as grounds for divorce, they certainly didn’t see it as an excuse for the wife to go outside the marriage. For them, a woman’s adultery was one of the really big aveirot, sins, up there with murder and idolatry, and punishable, at least in theory, by death.

At the same time, the rabbis of the early Common Era found ways to support the role of the biblical pilegesh, a woman who would serve as a man’s bed partner without the sanction of marriage. For example, there’s a much-adapted story in The Sages of the Talmud, in Tractate about an itinerant rabbi who is assigned a “bride for the night” in every town he visits. By the medieval period, most commentators were restricting access to the pilegesh to kings, putting her out of reach for your average Itzik, and almost all rabbis today declare taking (or being) a pilegesh to be forbidden or at least frowned upon.

In fact, while non-Orthodox rabbis have become more lenient in recent years concerning premarital sex, they have pretty much held the line on extramarital relations. Not until 2001 did the Reform movement’s Central Conference of American Rabbis issue a responsum acknowledging acceptance of premarital sexuality, and that same committee issued a concurrent statement asserting that adulterous relationships, whether conducted in secret or with a spouse’s consent, are sinful and forbidden. Attitudes may have become more gender-egalitarian in rabbis’ disapproval of adultery, but the prohibition against sex outside marriage looms large.

I might have let the status quo continue indefinitely if I hadn’t experienced a significant libido surge. Out of nowhere, I began to feel an urgent desire to have sex again that I couldn’t ignore. After trying to ignore it anyway, I opened a new email account and signed onto a couple of dating sites, posting a smiling photo, my real age, and a profile statement much like the personal ad above—the one I’d been rewriting in my head for about five years. As I clicked on the button to activate each account, I felt a distinct frisson of “Am I really doing this?”—mixed with a sense of inevitability.

Of course, the creeps and pervs popped up in droves. You wouldn’t believe the number of guys who asked if my husband would be interested in watching or participating. I fended them off and stuck to my criteria, adding more after I found out that men outnumber women by a wide margin on heterosexual dating sites. He had to be at least a little younger than I am and no more than two inches shorter. No one who had never been married. No evangelizing Christians. No country-and-western fans. He had to be willing to send me a photo showing his face.

Among the weenie-waggers and weirdos, a few interesting men appeared: the ones who said they not only liked my smile but enjoyed reading my profile. I got props for good grammar and syntax and for honesty. One guy said he was happy to see a woman’s profile that didn’t read like a tortured ransom note. The most likely prospects seemed to be the men who were in a similar situation to mine: married but not getting any. If a first exchange turned into a lively online conversation, I would let the guy know that he was chatting with a graying, overweight woman enrolled in Medicare. The usual response was “No problem.”

About a month after I started on the dating sites, I connected with someone who was local, but not too local, and sounded like a nice man. We had a video chat. We met in person for a beer and talked for a couple of hours. He held up his end of the conversation and was pleasantly pudgy, with a friendly face. Two days later, I spent the evening at his place; he was married but, for work reasons, lived apart from his wife most of the time. The moment he entered me, something that had been broken inside was put back together. Sleeping with this man is the most life-affirming sex I’ve ever had. It may be the most life-affirming thing I’ve ever done.

By the way, my husband knows all about this. Long before I hooked up with the Friend With Benefits, I told him that I needed to end the sex drought and was taking steps to do so. Through copious tears, I related how something just snapped, my sex urge was where it was when we first met, and I was going to go nuts if I didn’t find an outlet other than sex-for-one. I also assured him that he was my beshert: I loved him, would always love him, would never leave him.

And he understood. He had seen this coming and didn’t know why I’d waited so long. He felt terrible that he couldn’t perform and said there wasn’t any way I could hurt him that life hadn’t already dished out. He wanted me to be happy. “I don’t want details,” he said, “but do whatever you need to do.” His sacrifice out of love only makes me love him more.

So here I am, a mature woman working in religious life, having joyous, guilt-free extramarital sex. The relationship has been going on for several months, with no diminution of my enjoyment, my FWB’s ardor, or my husband’s tacit support. (Of course, it has to be kept secret from pretty much everyone except my husband.) After all these years, having sex is like a wonderful, unexpected gift: from my lover, from my husband, and, I can’t help but feel, from God. The reach of the Sages just doesn’t extend to my life and circumstances. If my husband understands, I think God does too.

There’s another benefit to this new world: it’s been enormously healing. For the first 30 years of my life, I was told, explicitly and implicitly, that I was fat and ugly. My husband has always loved my face and body, but I figured he was an outlier, someone with quirky physical taste in women, and I was still fat and ugly. Then, on the dating sites, I found out that my husband’s taste wasn’t so quirky. I tapped into a well of men who like women with brains and big hips. For the first time in my life, I can look at myself in the mirror and like my body, even with the saddlebags and the long ribbons of stretch marks, the knee-replacement scars and the effects of gravity on my breasts and thighs. That’s almost better than multiple orgasms.

I’m neither proud nor ashamed of looking for sex outside my marriage, of engaging in something so taboo. But it was difficult to undertake something that has such potential for harm, and I don’t recommend it to every woman who hungers for sex in a sexless marriage. Your spouse may not be as understanding as mine, and sneaking around is a drag. I’m not a parent; if you have kids, that might add an extra layer of secrecy and guilt. You may not be as lucky as I’ve been in avoiding potentially dangerous men and situations. Your fear of being exposed may outweigh the pleasure you receive. You may not be able to handle the emotional roller coaster that results from simultaneous intimate relationships with two people, especially if the FWB really is a friend and your spouse is your best friend—but not, in this case, one in whom you can confide.

That said, I’m not sorry I went this route. Chalk it up to self-care, which religious professionals are repeatedly told to make an important part of their lives. I missed having sex, and having it makes me happy. The only thing that would make me happier would be if my beshert got his mojo back. Then all of me could devote myself to all of him, and only him.

Art: Berthe Morisot, “Getting out of Bed,” 1885-1886

- No Comments

January 25, 2021 by Sarah M. Seltzer

Amy Coney Barrett and Me

As the world watched Amy Coney Barrett on display in the Senate judiciary hearings, I practically heard the sound of bewilderment erupting in viewers’ heads. It’s like the noise that your Waze makes when you make a wrong turn and then she has to adjust her entire plan. It’s that scratchy sound of reconfiguring.

The disconnect has to do with the realization that Coney Barrett has two sides. She is on the one hand a smart, competent career woman, and on the other hand also a voice for repressive patriarchal ideas.

But she is hardly alone. We don’t need to go all the way back to Phyllis Schlafly to find examples of WPPs—that is, Women who Protect the Patriarchy. We have plenty of examples of women like that today. I’m not just talking about the women on the public stage like Sarah Huckabee Sanders, Kimberly Guilfoyle, or KellyAnne Conway, women who have dedicated their public-facing careers to being mouthpieces for patriarchal power.

No, I am referring to a different dynamic. I am talking about women for whom the patriarchy is personal. Women who live it while defending it. An Orthodox Jewish woman, for instance, maybe the head of the brain surgery department at a hospital but accept that she doesn’t count in a minyan and her voice can never be heard in public. She may even be a brilliant musician while accepting the reality that she cannot sing in front of men, or an outstanding athlete who would never run in anything other than long sleeves and a skirt.

I know this stance well, because I lived it. I was expanding my horizons beyond what my female ancestors did—getting an education, working, earning money, speaking out—while at the same time finding my place in the women’s section behind the partition. Keeping my shoulders covered. Participating in ritual practices where I did not count and my voice could not be heard. My head was making that reconfiguring noise but it took me a while to notice the sound, or to figure out what it was saying to me.

It makes sense: pushing back against your community and everything you’ve ever known often comes at great personal cost. Women everywhere pick and choose our battles. Look at how liberal institutions—women included—have tried to sweep #MeToo incidents under the rug over time. All women are in some kind of negotiation with the patriarchy. None of us has fixed our worlds yet, so we all choose to shut out the noise.

The issue Coney Barrett’s hearings evoked, though, is that the stakes are greater when women who are protecting the patriarchy enter leadership. Then, the contradiction can take a sinister turn. Religious women can use their newly acquired power to keep other women in their place.

Coney Barrett especially reminded me of learned women like yoatzot halakha, women halakhic advisers, who are breaking barriers while using their platforms to protect patriarchal Jewish practices. Yoatzot have been among the first women allowed to take a role that for generations was the domain of male rabbis—advising religious women on ritual immersion and halakhic menstrual “purity.” No matter how you try to parse these laws or how many books are written about the “benefits” of these practices, there is no way to escape the fact that they are based on ideas that are terrible for women: that the purpose of our sexual lives is to procreate, that our menstruation makes us “impure,” that there is no such thing as non-sexual physical contact between men and women, that men cannot look at their wives without wanting sex, and that women’s most intimate body care is under the purview of rabbis. For generations, women have been showing their stained underwear to rabbis to rule about whether they could have sex with their husbands. The yoetzet position brought a welcome change: women with questions about their “purity” could at least show their underwear to a woman instead of a man.

On a closer look, though, you will often hear learned women insisting that they are not making actual rulings but merely acting as vehicles for men, the genuine voices of Jewish authority. Like Coney Barrett, they are exercising “judgment,” and “power” but only to support a sexist structure.

I grew up with female gatekeepers. The Rebbetzin in my post-high school seminary who taught us that head covering was a law brought down from Moses at Sinai. The teachers who monitored the lengths of our skirts, who reminded us that we were not “obligated” to pray mincha because we were just girls. The nice young teachers who, in twelfth grade, took us on an exclusive and exciting field trip to the local mikveh, to school us in getting ready for sex in marriage. As if ritual immersion is all you need to know about sex. And then years later, the local Rebbetzin who gave me “kallah classes” that traumatized me in ways I could not articulate.

It is hard to break away from the patriarchy, but even harder when you’ve been indoctrinated by women, women who appear warm, and speak about meaning, connection, tradition, and of course God. I call this Indoctrination with a Pretty Face.

But female gatekeepers can also indoctrinate with force. My mother aggressively groomed us—my three sisters and me—for a life of servitude as wife and mother, and as an object that was pleasing to men. It wasn’t just my clothing, my body, my face, and my food that were managed and monitored. It was also my words, my behavior, my demeanor. A girl who ate too much, who spoke too much, or who stayed seated at the Shabbat table instead of serving, was bad. A girl who challenged her father’s ideas, who ate before her father ate, or who dared get up from the table before the father declared it done, was worthy of disdain. Embarrassing.

All this was to prepare us for marriage. “Behind every successful man is a woman” were words that we lived by. And yet, even though we were taught that women’s open ambition was ugly, we were encouraged to get an education. The same way we were told we must get a driver’s license, as a kind of protection, but we were never expected to drive. Women’s driving was considered unnatural! My father mocked women drivers, including his daughters, and would never get into the passenger seat when a woman was driving. Nevertheless, my mother ensured that we got licenses, just as she wanted to make sure that we all got a Bachelor’s degree, and even a part-time job if we insisted. It was a back-up plan, not to be confused with a career. I mean, the idea of one of the daughters becoming an independent woman was almost as appalling as becoming fat.

Somewhere in the back of my brain, hearing all this, there were screechy sounds trying to get my attention, but they were blocked by messages that we had the secret to women’s success. Plus, once you pay attention to the screechy sound, once you start to question the premise of your way of life, well, the whole thing can come down like a house of cards.

That is what happened to me, though the process took 30 years.

For a very long time, the idea that this whole identity was in conflict with itself was too hard to unpack. So I took down little pieces, one at a time. Took off my hat. Started sharing roles at home. Pursued a doctorate. Made kiddush. Sat down while my husband vacuumed. Fought for agunot. Added Miriam to the Seder. Drove while my husband sat in the passenger seat.

But the thing is—and here is where it gets tricky—even while I was sorting it all out internally, externally I was still acting as a megaphone for the patriarchy. I taught religious high school girls, spitting out the same language that today I find intolerable, rhetoric about the beauty of women’s modesty, the wisdom of the halakhic system. Once when a friend of mine shared with me that she had stopped going to the mikveh, I reacted with horror. She still reminds me of that, just for fun.

One day in my sophomore year at Barnard, I was in a lecture hall listening to a class about gender and politics. In a discussion about the evolution of ideas about women and child care, I raised my hand and said, “But everyone knows that children need their mothers. Everyone knows that a child who grows up in daycare is going to be messed up.”

You can imagine the uproar. People who know me today probably don’t even believe the story. But I came from a very different place. I could have continued on my path. Perhaps had things been smoother for me, I would still be there. I think that it is very possible that I could have been an Orthodox version of Coney Barrett. One of my sisters is a yoetzet halakha. Another sister wanted to be a doctor, but did not go to medical school because she kept saying (as I did that day in Barnard) that a woman cannot be a doctor and a good mother. Sometimes I would say to her, ‘Just do it, just go to medical school.’ And she would yell back at me, ‘I don’t need any of your feminism!’ Our conversations never ended well.

Today, we are no longer on speaking terms. It was my choice. And yet my sister’s story is also my own. The messages she got are the same ones that I got. Marry early. Have lots of kids. Be a good mother. Dedicate yourself to everyone else. Oh, and do all that while being thin, pretty, perky, happy, smiling, and servile.

Had I not been unhappy with my life, I would have stayed in that world. I challenged what I was living with not because it didn’t make sense but because I was being emotionally and sexually abused. And even despite that, I tried to make it work for a long time.

It is not hard for me to imagine how a woman can be both a career-go-getter and also a defender of her religious patriarchy. In fact, these personality traits may even go together well. Religious women are often good students—smart, diligent, hard workers. And not even just religious girls. It takes a lot to manage the kinds of lives that working mothers of big families manage. It’s a lot of organizing and thinking ahead, attention to detail, multi-tasking, and problem-solving. To wit, in Israel, Haredi women are considered outstanding employees. They tend to be efficient and punctual, they get a lot done in a small space of time, they do not stand around drinking at happy hour, and they are reliable.

Maybe it’s no wonder women like Coney Barrett go far. In places where diligence is rewarded, religious women are well suited. You don’t always need to be creative to get ahead. You sometimes need to do what is expected. That quality fits in quite well with being an obedient religious woman. Her behavior at her confirmation hearings reinforced that impression—she hardly articulated any independent thought, and maintained a resolve that enabled her to get through the grueling process without getting her hands dirty or ever sharing a single personal belief.

At the end of the day, Coney Barrett was well-rewarded for her performance as the perfect patriarchal woman. She demonstrated a deep and powerful reason why women—even smart, thinking, self-driven women—sometimes become the great protectors of the patriarchy. And that has to do with what they get out of it. For them, the system works. Not only does it work, but it offers compelling rewards.

You know where to go and what to do all the time. And while a house full of kids is a LOT of work, it is also at times comforting in its busyness. Predictable trips to worship are vital for so many people—less because of prayer and more because of community. Coney Barrett may love her “People of Praise” group where her highest position as a woman might be “handmaiden” as opposed to “leader” because it gives her all the same kinds of benefits that women get in Orthodoxy—community, belonging, identity, friends, structure.

Succeeding in the patriarchy offers what Viktor Frankel argued may even be more powerful than love: purpose. Gender equality is a nice idea. But then there is what really drives us.

Not all of our choices are consistent. I hear accusations in feminist circles all the time. You cannot be both a feminist and a mother of lots of children. Or a feminist and financially dependent on a husband. Or a feminist who gets plastic surgery. Or a feminist and mother of soldiers. Or a feminist and a Zionist. Perhaps all of us, in some way, are gatekeepers for parts of the patriarchy. Maybe it’s unavoidable. After all, the patriarchy is the very water we swim in. But in that water, we still have choices. Coney Barrett made choices. My mother made choices. And I made choices.

Yet if our personal choices are private, once they become public stances, it is a whole different game. If Coney Barrett chooses to embrace patriarchal lifestyles—such as her participation in “People of Praise”—she has every right to be in that place. But once she is a Supreme Court Justice, then she is not just a woman in conflict. She has ironically broken a glass ceiling, but only to use her position to inflict some great harm on other women. If the Supreme Court knocks down Roe v. Wade or cancels birth control coverage, then Coney Barrett becomes a damaging agent of the patriarchy. It doesn’t matter that she happens to be a woman.

Photo: Kai Medina (MK170101 via Wikimedia Commons)

Dr. Elana Sztokman is an award-winning author, researcher, educator, and activist.

- No Comments

January 25, 2021 by Sarah M. Seltzer

From the Editor: How Are We, Really?

A former staffer in the Lilith office would always answer the perfunctory “How are you?” question with an enthusiastic, “I’m doing great, thanks. How are you?” These days, both the question and its cheery, upbeat rejoinder seem out of place. We’ve had to change how we say hello and goodbye.

“Sholem Aleichem” is the common greeting in Yiddish, with its reflexive response: “Aleichem Sholem.” I would hear this exchange as a child, both from elders via the Old Country and from younger folks paying their respects not as mimicry but with an understanding of how sweet the underlying sentiment is: “May peace be upon you; Upon you may there be peace.” I always loved the sureness with which this exchange was conducted. Identical in Hebrew, we traditionally chant the lines as an opening to Sabbath rituals. In Arabic the words are the same. The beseeching and its underlying wish are kindly, benign, sincere, maybe even a little banal. Fair enough. These days we would settle for such hopefulness with which to start any encounter.

But greetings like “How’s it going?”—or even “How are you?” which really demands no answer—feel off-limits to us now, as does that blithe “I’m doing great.” Now, we have to probe deeper. None of us can assume anymore that the person on the other end of any conversation is free from suffering, and I find myself beginning even a simple business email (maybe you do the same) asking for reassurance: “I hope this finds you well, as well as circumstances permit.” Our openings are fraught with the underlying assumption that all lives are under threat this very moment, not something most of us have had to consider during our lifetimes, and never for so long. Certainly after a terrible natural disaster, or 9/11, or—recently and horribly—attacks on synagogues, other houses of worship and peaceful demonstrations. But now the onslaught feels consistent, and long-lasting, with no certainty as to when, or even how, the pandemic will end.

Approaching the one-year anniversary of when the Covid-19 virus broke into our consciousness and our communities, I’ve been thinking about how my everyday exchanges signify a different kind of connectedness and concern than they did before. Even strangers now conclude a routine phone call with “Stay safe.” And we now attend to and value the labor of the grocery store clerk and the delivery person—to say nothing of health care workers and eldercare aides who make possible such limited safety as we are able to muster.

Traditionally, religious Jews respond to the pro-forma greeting “How are you?” with “Baruch HaShem,” thank God. Today, even for non-believers, this pious response may connect with how we’re feeling—and I don’t mean merely religion-by-rote, wherein this response can be as unthinking as saying “Bless you” by reflex when you hear a sneeze. (Of course, in our present circumstances, if anyone sneezed you’d run for cover and wash your hands.) What I mean is that I am perpetually conscious of feeling grateful. You too? Despite horrendous losses of life and of health, losses of jobs and prospects and plans for the future, we hear all around us “I feel lucky to have food to eat, or …a place to live, a friend to call….” Or for a book to read, a podcast for company, or a few minutes to spend with a kid talking about something other than the virus’s disruptions and dangers.

Along with recalibrating how we greet people, we’re redefining what constitutes happiness for us now. We’re grateful on this small scale at the same time as we recognize the poisonous behaviors from callow and careless officials who were entrusted with public health and safety and who instead cast aside science, good sense, empathy, responsibility and more to exacerbate our danger rather than ameliorating it.

So, how will our new greetings, with their concern for and gratitude toward others, translate on a larger scale? Dare we hope that even if our own prospects shrink we’ll nonetheless look for ways to help others grow theirs? You know that characteristically the poor give more generously to charity, as a percentage of income, than do the wealthy. Will those who have prospered begin to give more, both to meet daily needs and to drive our society towards justice? Will the gratitude for our own small and large blessings spill over into good deeds, so that we can be reasonably sure down the line of having good health and good government, more fairness and less bias, more food and less hunger, more safety and less peril? May it be so. And may peace be upon you. Sholem Aleichem.

Susan Weidman Schneider

Editor in Chief

- No Comments

January 25, 2021 by Sarah M. Seltzer

QAnon and its Dangerous Appeal to Women

After Joe Biden was declared the winner of the 2020 presidential election, I joined so many others in allowing myself to feel relief, and, yes, joy. The violence we feared coming on Election Day did not materialize, and it appears that American democracy, so far, survived Trump. But we’re in no way out of the woods: As of publication time, Trump refuses to concede, and is threatening to run again in 2024. After four weary years of threats to just about everything that defines civil society, we will be left facing many evil genies these years have uncorked.

Among the most malignant is QAnon.

Here, in part, is how Wikipedia defines this loose coalition in Fall 2020: QAnon is a far-right conspiracy theory alleging that a cabal of Satan-worshipping pedophiles is running a global child sex-trafficking ring and plotting against US President Donald Trump, who is fighting the cabal. QAnon also commonly asserts that Trump is planning a day of reckoning known as the “Storm”, when thousands of members of the cabal will be arrested. No part of the conspiracy claim is based in fact.

You heard a lot about QAnon during the last crazy months leading up to the election. It became a bigger story after a QAnon supporter, Marjorie Taylor Greene, a Republican, won a Congressional seat in a deep-red section of Georgia. Trump tweeted his congratulations to her, calling her a “future Republican star.” Around this time, we began reading about QAnon all over the media, and seeing photos of people at rallies sporting Q hats and other paraphernalia.

Some call QAnon a “conspiracy theory,” but that’s too simple a definition. QAnon is more like a collective delusion. The Global Network on Extremism and Technology, a think tank studying how terrorists use technology, based at Department of War Studies at King’s College London, defines QAnon as “a militant and anti-establishment ideology rooted in a quasi-apocalyptic desire to destroy the existing, corrupt world order and usher in a promised golden age.”

Up until the election, Q-followers shared one core belief: That Donald Trump will lead a holy war against Satan, aka “the deep state.” In other words, people and institutions associated with liberals: the Clintons and the rest of the Democratic establishment, Hollywood figures (a favorite target is Tom Hanks), mainstream media, and, yes, George Soros.

All of these people, Q-ers believe, are really a gigantic pedophile ring that kidnaps children and harvests their blood. Sound familiar? There’s an obvious subtext of anti-Semitism in these tropes. The Jew as devourer of Christian children, who controls the banks and the world. These images date from the Middle Ages. In the 20th century, they got incorporated into the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion” and then the Nazi propaganda machine.

It started at the fringes of the web early in Donald Trump’s malignant presidency, when the anonymous Q began posting cryptic messages—“drops.” From there Q content migrated into mainstream social media. Followers create deliberately misleading hashtags, such as the innocuous sounding #Savethechildren, thereby drawing in people who might think they’re on a UNICEF-sponsored site, but instead find themselves reading posts like “Better be careful all these kids disappearing and burgers costing next to nothing at all the $2 burger etc. Human meat, you may be eating kids, Say no to fast food burgers.”

Q also hooks in people via their “drops;” searching for and decoding drops for some becomes an addiction. People who’ve fallen down this rabbit hole liken it to getting trapped in a cult.

With so many arms and no clear hierarchy, QAnon is a protean monster, mutating and multiplying like cancer cells, and it is precisely its adaptability to today’s climate that makes it so scary. QAnon, like a sewer flowing through the Internet, collects and absorbs every piece of noxious substance that passes into it from the waste pipes of our culture.

QAnon is not just online. In 2019, the FBI was labeling it a domestic terrorism threat. On the night of Election Day in November, the police in Philadelphia arrested two men at a polling site in a Hummer filled with guns and QAnon literature. Some journalists who wrote about QAnon have gotten death threats. Social media giants Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram keep telling us that they are clamping down on Q content, but this is way easier said than done because of its very protean nature.

But the election is over, Trump was defeated, and QAnon has lost the anointed leader. Need we still worry about the phenomenon and its paranoia? Won’t it just now shrivel up and crawl under a rock? Not so fast. During the fraught week after the election, “Q” went missing. But then he—she?—reemerged, and Q-followers threw out new conspiracy theories onto the Internet. One in particular caught Trump’s attention: Dominion, a manufacturer of voting machines, deleted millions of Trump votes. Trump promptly retweeted it (in all-caps.)

We shouldn’t expect QAnon to go away, but to continue mutating and multiplying. Especially now, in the midst of the pandemic: Catastrophic times are when conspiracy theories thrive (think the Middle Ages, when people blamed the Black Death on the Jews). To that add the fact that for the last ten months, people are isolated at home, glued to their Facebook and Instagram accounts.

As people try to make sense of it all, they pick up the QAnon content hiding behind benign-seeming hashtags and posts. Last summer, Instagram followers, as they scrolled through the site’s panoply of images showing candy-sweet home and-child-oriented consumer products, were also reading that the web-based furniture company Wayfair was really a child trafficking ring. The crazy rumor soon was ripping through social media like a bat out of hell. The Q craze has spread all over the globe, according to Marc André Argentino, a doctoral student at Concordia University who researches QAnon. According to Argentino, QAnon has migrated via social media into more than 70 countries. It has been particularly embraced by the far right fringe in Germany, the New York Times reported in October. Moreover, here in the States, even with Trump gone, QAnon remains in the mainstream. In November, more than a dozen QAnon supporters, all Republicans, ran for Congress. Two— both of them women—won: Marjorie Taylor Greene and Lauren Boebert, from Colorado.

In fact, it turns out that QAnon especially appeals to women.

And this is why, in addition to being a Jewish issue, QAnon is an unrecognized feminist one as well.

Many of today’s far-right movements are testosterone-driven—think Proud Boys and Oath Keepers—replete with muscular imagery. QAnon, on the other hand, attracts women—especially mothers—associated with Trump’s “base”: White, Christian, and not college educated. Likely what happened is that women seized on those aspects of QAnon content that fed preexisting fears—pedophilia, for example—and made it their own. Within the broad anti-trafficking movement, there has always been a moralistic streak, and this movement seizes on that. Women are organizing anti-child trafficking rallies, and posting like mad using #Savethechildren and its countless hashtag variants (#childtrafficking, #DefundHollywood, etc.), where they rant about how Joe Biden is a pedophile, and claiming that the Etsy site sells child porn.

QAnon content has also been creeping into yoga and wellness sites, where you can now find posts in girly fonts about Covid 19 being fake news, and how vaccinations are really a government-led attempt to kill your children—all against backgrounds of pale soothing colors. Argentino, the Concordia University researcher, calls this phenomenon “pastel QAnon.”

“These influencers provide an aesthetic and branding to their entire pages, and they in turn apply this to QAnon content, softening the messages, videos and traditional imagery that would be associated with QAnon narratives,” Argentino wrote on Twitter in September. “This branding is the polar opposite of ‘raw’ QAnon.”

In 1930s Germany, women went crazy for Hitler, and the Nazi Party specifically targeted them through their propaganda machine. Six weeks after Hitler took power in 1933, an exhibit entitled “Die Frauen” opened in Berlin, and Hitler’s propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels gave a speech. “This is the beginning of a new German womanhood,” Goebbels said. “If the nation once again has mothers who proudly and freely choose motherhood, it cannot perish. If the woman is healthy, the people will be healthy. Woe to the nation that neglects its women and mothers. It condemns itself.” At this time of extreme anxiety throughout the world, when misinformation gets transmitted via social media in one second, it bears repeating that the Nazis used whatever media they had at the time to broadcast their vile message. They used children’s books, posters, movies, board games. How primitive such media seem today! Yet they managed to convince Germans of the necessity of a Final Solution to the Jewish “problem.”

Is there a parallel between the Nazi ideation and tactics then and QAnon today?

One big difference between the Nazis and QAnon is just how organized and sharply focused the Nazis were, and how they drew on the systemic anti-Semitism in Europe that dated back to late antiquity. QAnon, in contrast, is much murkier. But QAnon’s goals—a world violently purged of “Satan,” code for liberals, Jews, Hollywood and elites, bears resemblance to the Nazis, who started a war and designed death camps for Jews and other “undesirables” as part of their plan to establish a 1000-year Aryan Reich.

Is it too much of a stretch to make this comparison? We don’t know yet. What we do know is that QAnon has capitalized on how easily misinformation floods the Internet, available to anybody who clicks on a link, and on the other hand attached itself to a resurgent right wing with an anti Semitic flair.

How scared should we be?

Photos: Flicker, Becker1999

Alice Sparberg Alexiou, journalist and author of three books, is a contributing editor at Lilith.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...