Tag : Eleanor J. Bader

November 5, 2019 by admin

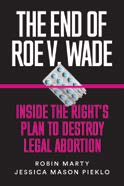

The Right’s Plan to Destroy Legal Abortion

Forty-six years after the US Supreme Court ruled that state bans on first trimester abortion violated the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of privacy, a well-organized and well-funded anti-choice movement remains hellbent on ending access to both surgical and medical (mifepristone followed by misoprostol) procedures.

Forty-six years after the US Supreme Court ruled that state bans on first trimester abortion violated the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of privacy, a well-organized and well-funded anti-choice movement remains hellbent on ending access to both surgical and medical (mifepristone followed by misoprostol) procedures.

This isn’t new.

- No Comments

May 16, 2018 by Eleanor J. Bader

Leslie Cagan’s Half-Century of Activism

When Brooklyn for Peace named community organizer Leslie Cagan one of three Pathfinder for Peace award winners in late 2017, it was both in recognition of, and in gratitude for, Cagan’s more than 50 years of social justice activism. Whether pushing for action on climate change, peace, LGBTQ equality, feminism, reproductive choice, or fighting racism, Cagan’s voice, presence, and expertise have long been visible.

Cagan has worn a lot of hats over the years. Among them, she was the interim board chair at the Pacifica radio network in the late 1990s; was National Coordinator of United for Peace and Justice from 2002-2009; and either coordinated or played a leadership role in some of the largest demonstrations in American history—for nuclear disarmament in 1982; for LGBTQ rights in 1987; against the war in Iraq in 2003; and for climate action in 2014.

Opening comments from Leslie Cagan, a leader in the Peoples Climate Movement NY – Peoples Climate Movement 2018 Kick-off event is a city-wide organizing meeting on learning how you can get more involved in climate campaigns. Followed by brief updates on the exciting work of several campaigns and breaking groups focused on how we can strengthen and expand climate action in New York City and NY State, as well as nationally. (Photo by Erik McGregor)

She is presently involved with the Peoples Climate Movement (PCM)—NYC, as well as PCM nationally, and is part of an effort challenging the corporate saturation and over-policing of the Heritage of Pride parade held annually in NYC to commemorate the 1969 Stonewall rebellion.

Cagan recently spoke to Eleanor J. Bader about her history, ongoing work, and the personal challenges of caring for life partner Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz, who has advanced Parkinson’s Disease.

Eleanor J. Bader: Let’s start with your personal history. When did you become involved in progressive political activism?

Leslie Cagan: I grew up in the Bronx, in a Jewish, leftist community. My parents were hardcore activists. I have an older brother and a younger sister and family outings growing up would often involve going to a demonstration. My grandmother was active in the textile workers union so I guess you can say that politics has always been in my blood. Their example was important and impacted all of us. Both of my siblings are activists. (more…)

- 2 Comments

April 12, 2018 by admin

Jewish Lesbian Feminist Goes Undercover to Report on the Alt-Right

When award-winning journalist Donna Minkowitz attended a conference sponsored by the innocuously-named American Renaissance organization last summer, she knew she would be rubbing elbows with leaders of the alt-right.

Minkowitz, a self-described “secular, Jewish, lesbian feminist and leftist,” told Eleanor J. Bader about covering the event for Political Research Associates, an independently-funded social justice think tank based in Somerville, Massachusetts. She also spoke about her earlier interactions with conservative organizations.

Eleanor J. Bader: You began reporting on the right-wing back in the 1990s. How and why did you get started on this beat?

Donna Minkowitz: I was the Village Voice’s reporter on LGBT issues, and when the anti-gay Christian right started to become active again in the 1990s, I found myself becoming increasingly terrified… I decided to cover it for Out Magazine. I was in my late 20s at the time and went completely undercover—I wore conservative, feminine dresses and a very femme-y wig. It was a really intense few days.

EJB: Did this year’s AmRen conference have a particular theme?

DM: The main message was that white people are smarter and better than everyone else and if only these “inferior” people of color were not around to drag them down, they could achieve the great things they imagine. AmRen says it welcomes Jews, but anti-Semitism was at the conference—it was hiding in plain sight. Eli Mosley, the head of the virulently anti-Semitic Identity Evropa, was at the conference and he and other attendees continually tweeted anti-Semitic messages; there were also loads of anti-Semitic books for sale, including The Turner Diaries, which advocates Jewish extermination…

EJB: Were you surprised by anything that you saw or heard?

DM: I was pretty stunned by how Handmaid’s Tale-ish their plans for women in the “white ethnostate” were.

- No Comments

April 8, 2014 by admin

The Midwife’s Narrative

According to midwife-turned-memoirist Ellen Cohen, when people hear the word midwife they typically assume that it refers to someone who assists women giving birth at home. But while this is certainly true for some in the profession, Cohen’s engaging account of the three decades she spent delivering babies, providing general gynecological care, and educating patients about abortion, contraception and sexuality aims to set the record straight.

“More than 95 percent of midwife deliveries in this country take place in hospitals,” she writes. It’s a setting Cohen knows well. During her tenure, she worked in both public and private facilities and estimates that she delivered at least 1400 babies, the offspring of the homeless, the HIV-positive, the indigent, the mentally ill and, of course, the perfectly healthy.

One of the most riveting stories she tells in Laboring: Stories of a New York City Hospital Midwife (self published; available at Amazon, $15.95) involves Mia, a woman diagnosed with schizophrenia who refused to believe that the intense pain she was feeling had anything to do with parturition. “I’m not pregnant,” she screamed. “Get your hands away from my pussy…No, I don’t use drugs…Just my Thorazine and my crack.”

Mia had been taken to the hospital by Emergency Medical Services after she was discovered in a mid-Manhattan subway station. She was terrified. “Mothers feel intense pressure from the baby’s head and a burning sensation in the perineum during the moments just before birth,” Cohen explains. “Mia must have been feeling that; she jumped over the raised side rails and out of bed, as if that would help her escape the pain, and ran out of the room into the large open area near the nurse’s station. After a split second of shocked disbelief, I ran right behind her. Mia leaned against the wall with the next contraction as the baby’s head emerged.” Cohen encouraged her to crouch down, and an incredulous Mia delivered a healthy baby, subsequently placed with the same relative who was caring for Mia’s first-born daughter.

Cohen admits that patients like Mia, while relatively rare, take their toll on staff. Likewise, the unanticipated stillbirths, birth defects, and other complications have a jarring impact on midwives and other medical personnel, underscoring the dangers inherent in pregnancy, no matter how sophisticated the technology or how good the prenatal care.

The story of Tonia is a case in point. Thrilled to be having a girl, Tonia was a young, healthy non-smoker who did not drink or use drugs. Everything was going perfectly, the baby kicking and growing normally. Then, out of nowhere, Tonia developed pre-eclampsia, a serious pregnancy complication that caused the baby to be born 12 weeks early. The infant later died, and Cohen’s description is heart-rending.

That said, all is not grim, and Laboring includes dozens of joyful anecdotes. At the same time, Cohen reports encounters with arrogant, sexist physicians and pig-headed bureaucrats. She also chronicles several just-in-the-nick-of-time actions by helpful maintenance people — the usually unheralded workers who keep health centers running smoothly. What’s more, while the book does not directly tackle deficits in the healthcare system, it addresses — and condemns — the high rate of Caesarian deliveries in the United States.

Cohen notes that midwives are trained to let nature take its course, and the profession favors a “high touch, low tech” approach over a “high-tech, no touch” medical model for women about to give birth. “Pregnancy,” Cohen concludes, “is not a disease. Midwives trust birth rather than trying to control it. Science supports this approach.”

And if it takes longer than one might like? Cohen acknowledges that labor follows neither formula nor game plan. “We do not view the normal mainly as preparation for the interesting complication,” she writes. “The ordinary miracle of life is interesting enough.”

Eleanor J. Bader is a writer and teacher whose work appears on Truthout.org, RHRealityCheck.org, Theasy.com and in The Brooklyn Rail and other progressive feminist magazines and blogs.

- No Comments

April 8, 2014 by admin

Human Rights Plays Rooted in Dark French Books

Award-winning playwright Catherine Filloux credits her grandmother and her high school with kick-starting her interest in human rights and feminism. And the duality has led her to write more than 20 internationally produced plays and libretti.

Filloux recalls that when she was very young her paternal grandmother, living in France, would read aloud to her during visits. “Although I grew up in San Diego, French was my first language, and my grandmother used to read these dark French books to me,” Filloux begins. “I remember one, Francois Le Bossu, Francis the Hunchback, by Comtesse De Segur. It was very old, published in 1930, and was about a disabled boy. It asked the reader to empathize. There was a lot of dialogue in the book, with characters speaking in turn, as if in a play.”

Later, as a high school student in the late 1970s, Filloux began studying the Holocaust. “For me, the Holocaust stands as a catastrophic watershed moment that we’ll never put behind us,” she continues. “My paternal grandparents, who were not Jewish, lived in Occupied France and participated in the Resistance. They took in a Jewish boy who lived with them for years; my uncle, my father’s brother, was also active. When we studied this history in school we learned the phrase ‘never again,’ but what do these words mean when genocides continue to happen in other parts of the world? That’s the big question, and it refuses to go away.”

In fact, it forms the crux of Filloux’s 2005 play Lemkin’s House, pictured here. The drama is about Raphael Lemkin, [1900–1959] the Polish-Jewish attorney credited with coining the term genocide and with drafting the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, first presented to the United Nations in 1948. “I learned about Lemkin from Samantha Powers’ 2002 book, A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide. Lemkin became like a soul mate for me,” Filloux explains. “Early on, before Hitler became powerful, Lemkin went to his family and told them, ‘We have to leave. Something terrible is going to happen here.’ They refused, thinking they’d be fine in their village.” The upshot was that Lemkin lost 49 family members — everyone except one brother.

Despite these compelling facts, Filloux was not interested in writing Lemkin’s biography. Instead, she says that she began by imagining Lemkin’s death, and opens the play with him in limbo. “It’s a surreal look at his situation,” she says. “He has survivor’s guilt and is haunted by both his mother and the genocides in Bosnia and other places. Among other things, the play is about forgiving himself for leaving his family behind.”

Filloux’s other plays tackle cultural dislocation, immigration, honor killing, mourning, rape, and political activism. “Eyes of the Heart” addresses the plight of 150 Cambodian women, imprisoned by the Khmer Rouge, who became psychosomatically blind in response to the horrors they’d witnessed; “Dog and Wolf” focuses on the mass killings in Bosnia. “Memory can be revolutionary,” Filloux says. “By remembering you can plant seeds for change. Acknowledging vast suffering — remembering, retelling and re-acknowledging — asks an audience to empathize, to somehow get involved.”

That said, Filloux is adamant that her plays are not overtly political. “They’re character-driven stories,” she says, and while humor sometimes peeks out, she emphasizes that she writes about topics that demand attention.

Why plays instead of journalism or narrative accounts? “I’m drawn to the collaborative aspect, to the physical embodiment of characters onstage so that the writing lives in a community, through the audience.”

Catherine Filloux (catherinefilloux.com) will be leading an international playwright retreat in Italy August 1–August 10, 2014, for the La MaMa Umbria International. “Selma ‘65” will receive its world premiere from September 25th to October 12th, 2014, at La MaMa in New York City.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...