Tag : Chanel Dubofsky

January 26, 2021 by Sarah M. Seltzer

Truths from Private Spaces

As an undergraduate Jewish studies major, I stuffed my brain and bookshelves with the literature of Jewish feminism: Nice Jewish Girls: A Lesbian Anthology, On Being a Jewish Feminist, Joining the Sisterhood: Young Jewish Women Write Their Lives, Yentl’s Revenge: The New Next Wave of Jewish Feminism, Like Bread on the Seder Plate: Jewish Lesbians and the Transformation of Tradition. These books lit up my curiosity, my politics, and my indignation. Now, Monologues from the Makom: Intertwined Narratives of Sexuality, Gender, Body Image, and Jewish Identity (Ben Yehuda Press, $14.95) confronts the taboos of sexuality and women in the observant Jewish community through first-person poetry and prose. It deserves a space among the classics.

Monologues is composed of truths that until now, have been spoken about in dorm rooms, synagogue bathrooms, camp bunks, and on Shabbat afternoon walks, but have never been rounded up and presented to the world. While religious expectations—modest dress, not touching the opposite sex until marriage, observing the laws of ritual purity, dominate the text, the reality is that all women will recognize themselves in these pages.

You don’t have to have spent years in a Modern Orthodox Jewish day school to know that consent is a rusty, if not completely unknown, and even threatening concept to many. You don’t need to have experienced pregnancy or sexual assault. What we do collectively understand (even if we don’t quite know it) by virtue of walking around in our gendered bodies, is shame, and the work inside this anthology succeeds in facing it, cracking it open, and looking at its insides, all in the name of undercutting its power and letting the air out of tightly held secrets, and ultimately, assuring readers that they are most definitely not alone.

“My community preaches acceptance and love and that women have no place in Simchat Torah.” writes Jennifer Brenis in her poem, “Synonyms.” In the piece, Brenis articulates another experience that women know well: gaslighting. What we say happened didn’t happen, we’re overly sensitive, paranoid, fragile. What’s close and dear to us is used as ammunition. The authors in Monologues have spent their lives in Jewish communities; they build and sustain and fight for them, they have followed the rules. Yet all around them are voices telling them that while they’re allegedly vital to these communities, they’re not completely part of them, and the experiences they’ve had in them aren’t real, and what happens to them is their own fault. The anonymous writer of “Shame” wonders if her sexual assault would have happened her skirt hadn’t been short, and if perhaps “Orthodoxy is right and I should not be intimate with members of the opposite sex because this is what happens.”

Girls are taught to be good—don’t be (too) sexual, too aggressive, too loud, too

smart. If you’re Jewish, don’t talk about anything that could be seen as damaging, disloyal to the community, even when it’s the truth. It’s an exhausting order, not just tired, but stodgy and irrelevant. Between the pages of Monologues are testaments to the fact that telling the truth is radical, and so is Judaism. These writers know that telling the truth not only restores power to the truth teller, but has the potential to bring new energy to structures that could use some redemption.

Chanel Dubofsky is a writer based in Brooklyn, NY.

- No Comments

October 15, 2020 by Chanel Dubofsky

Connecting Jewish Tradition with Black Fugitive Legacies

This autumn, the parking lot of the Halcyon Arts Lab in Washington DC hosted a special sukkah built by visual artist Jessica Valoris. Though its materials—recycled cardboard, paper, bamboo and plant materials—are all things you might expect to find in your average sukkah. this one is anything but; it’s a structure that confronts the past and present, invites us to engage with possibilities of the future. Lilith spoke with Valoris about creating, Black fugitivity, spirituality, and more.

- No Comments

March 20, 2014 by Chanel Dubofsky

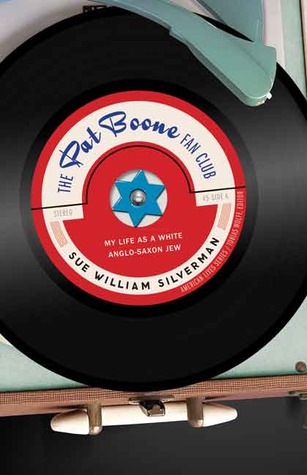

“I Wanted to Be Pat Boone’s Daughter.”

When Sue William Silverman and I met to discuss her new memoir, The Pat Boone Fan Club: My Life as a White Anglo Saxon Jew, she played “Exodus” for me on her iPhone. (Boone actually wrote the lyrics for the theme song for the movie Exodus, which lyrics he titled “This Land Is Mine.”)

Me: It sounds really…generic.

Sue William Silverman: Everything about Pat Boone is generic. That’s why I loved him, I could make him into anyone I wanted him to be.

Silverman’s memoir is a story of among other things, evolving identity, of wishing your reality wasn’t yours in the most profound way, of doing whatever it takes to escape it and become yourself.

Lilith: The Pat Boone Fan Club opens with a quote from James Baldwin:

“Identity would seem to be the garment with which one covers the nakedness of the self: in which case, it is best that the garment be loose, a little like the robes of the desert, through which one’s nakedness can always be felt, and, sometimes, discerned. This trust in one’s nakedness is all that gives one the power to change one’s robes.”

Can you comment on why you include this?

Sue Silverman: To me, this quote conveys the complexity of identity, which is what I explore in the book. How, when, and why do we change our identity? What parts of ourselves do we reveal?

For me, growing up in a troubled, incestuous family, I lost a sense of my true self, including a sense of my Judaism. Throughout the book, I tumble through various identities: I tried to pass as Christian; I tried being a kibbutznik, picking apricots in Israel; as a hippie, I tramped cross-country in a VW camper; I vacationed in Yugoslavia with a boyfriend who, it turned out, was anti-Semitic; I married – and divorced – two Christian men.

More than anything – and this is the heart of the book – I wanted to be Pat Boone’s daughter. I wanted that very Christian, squeaky-clean 1960s pop star to adopt me. Why? Because my father sexually molested me growing up.

But why Pat Boone? For hours, as a young girl, I gazed at photos of him and his beaming, golden family in fan magazines. If Pat Boone could raise four daughters, couldn’t he raise me, too? In my child-mind, he was the ideal of what a father should be: someone nurturing, caring, safe.

So the identity I most wanted was that of Pat Boone’s fifth daughter!

- 2 Comments

June 16, 2010 by admin

The Marriage Train

I’m not exaggerating when I say that if I had tried to get engaged or married while in college, I would have been in some serious trouble with my mother. I can hear her rant (albeit a made-up rant, but nevertheless, the sound of her voice is a stunning likeness) about how we had all worked too hard to get me there for me to blow it on anything other than more hard work, no distractions as crazy as marriage. She knew something about marriage; she was in one for sixteen years that ended unhappily, and she had given up admission to a prestigious nursing program to get married. I was supposed to do other things, and finishing college was only the tip of the iceberg.

The impetus for this post is the recent deluge of marriages I’ve noticed among Jews under the age of 23. My confusion is mostly based on the fact that the folks who are making the mad dash for the chuppah aren’t Orthodox or even Modern Orthodox, where the expectation of marrying and starting a family young is seen as an immediate priority.

I’m struggling to understand why this is happening, and why the Jewish community is so hell-bent on establishing it as a norm. It creates a strange and terrible kind of peer pressure, resulting in panic amongst the not married or partnered, and even resulting in those in committed relationships marrying before they’re ready (if anyone is ever really ready).

Marrying so young places an entirely different lens over the concept of matrimony-it’s no longer about taking years to find the right person and begin a life with them. Rather, it’s about starting out together, and hoping, believing even, that you will be able to overcome the hurdles that are inevitable when two people grow and change together. It seems particularly retro if you’re me, and along with your friends in their early 30’s, are either skeptical at best of the institution of marriage, or just starting to think about the idea.

It’s hard to explain to the newly minted college graduates around you that no, this behavior isn’t normal for most people their age. A marriage license and/or an engagement ring isn’t a requirement to receive a college diploma, although it seems like it might as well be. You can still be a member of a Jewish community without a ketubah on the wall of your apartment and with the last name you were born with. It should go without saying that all this is true, but it’s hard to believe when it seems like everyone else is doing getting married and/or engaged. Who will the role models be for young, single, serious Jews who don’t fit into or buy into this paradigm, especially young women? Only time can really tell us if young folks can resist the peer pressure to hurry and create a family (even if it’s not what’s right for them–now or ever) or if they will seek out other communities who can ultimately be more patient.

-Chanel Dubofsky

- 3 Comments

June 9, 2010 by admin

A Voyeur's Garb

I admit it–I’m an Orthodox voyeur (fetishist, you might call it). As in, I am guilty of a certain degree of exoticization of the Orthodox community. For a while, I was convinced that in spite of my relatively non-observant upbringing, I could become part of it (see “Pants Embargo, 2003-2005”). I was wholly unsuccessful at it- I didn’t become more religious, I just didn’t wear pants- although I think on the outside, people bought it. At least, they were quick to comment as soon as the jeans made a reappearance.

Some vestiges have remained, in the form of what I can describe as situations in which I feel like an anthropologist in communities that I am theoretically supposed to be a part of. Example most recent: the JOFA conference (Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance). I love this space, every time it comes around, I rearrange things so I can go. It’s a strange place for me to find comfort and inspiration, because I often also feel insanely frustrated by what I perceive as collusion with a system that consistently, actively and aggressively subjugates and invisibilizes women.

I’ve been listening to the recordings of the sessions I didn’t attend while at the conference, and thinking about the creation of space as I do it. I thought a lot about what to wear this year. Ultimately, I wore a skirt, which in hindsight, I shouldn’t have done. I felt like I was in costume, undercover, but also, fake. With the exception of a few people I knew, everyone who saw me that day thought I was an Orthodox woman. In the past, I would have been okay with that, even grateful for the association, but no longer, because it’s not who I am, or who I ever was.

Ultimately, the genius of the JOFA project, whether purposeful or not, is the opportunity for ingathering of all different types of Jewish feminists, the welcoming of the lenses and the narratives. In doing so, we (okay, me) have to confront what we find most disturbing, meaningful and joyful about Judaism, as well as put our heads together to change it. It requires patience and commitment, but it also requires an unpacking of assumption-about Orthodoxy, Jewish women, Jewish communities, and ultimately, what it means to be Jewish ourselves.

-Chanel Dubofsky

- 1 Comment

June 1, 2010 by admin

Reconceiving Jews

Last night, just for fun, I googled “childfree Jewish community.” (To be clear – the term “childless” implies that one wants children but does not have them for some reason, whereas “childfree” alludes to someone who’s happily without children and aspires to stay that way). What I found were feature articles written years ago, an assortment of alarmist opinions from rabbis and other Jewish communal figures on the declining Jewish birthrate, and one recent piece from Frum Satire called “I Don’t Want to Have Kids.”

As another Jewish woman who’s committed to living a childfree life, I was so excited to see this post, especially since it was written by a woman who’s committed to a halachic life. It’s hard to put yourself out there when you know you’re going to get skewered by your own community.

I destroyed my own bliss by reading the comments on Tova’s piece. It’s not like I haven’t heard most of them before-you’re selfish, you’ll figure it out when you’re older, you don’t know what you want yet, you have issues that you’re refusing to deal with. What wasn’t said was that in addition to being angry and frustrated, people are confounded by Tova (and me and every other woman who doesn’t want to be a mother). Who is a Jewish woman if not a nurturer, a creator? What does a Jewish woman look like if she’s not building a family or aspiring to build a family?

I’ve always known I didn’t want to parent, but I admitted it rather early. Now I’m 31 and my friends are on their second babies. I’m watching my avowed childfree life proceed as planned. In the secular world, people are confused and skeptical about my feelings, but in the Jewish world, it’s a different kind of message-a questioning. What are my priorities? How will I be a member of a Jewish community as an adult if I don’t have children? Don’t I feel a responsibility to the Jewish community to create more Jews?

The blogger and author Emily Gould said in a recent interview in New York Magazine, “I do think that people who write honestly about their lives are doing people who won’t or can’t a favor, to put it bluntly.” Part of writing honestly about your life is admitting that you don’t have answers, that everything you think and feel is complicated. This is especially true for women, since we’ve been socialized to not trust our instincts and therefore to dismiss our own emotions, lest we become consumed by them and be labeled hysterical. For me, there aren’t clear answers to the questions about what it means to be in a community that I consider to be mine when I feel at odds with it about so many things. There are only more questions.

–Chanel Dubofsky

- No Comments

May 26, 2010 by admin

Intention

This evening, as I was leaving the building I will be working in for one more day, I ran into Sam, a lovely man whom I don’t see often enough. As we talked, I told him that I’d be leaving the organization, he asked me what I’d be doing next. “I don’t know yet,” I said, “but I’ll be okay.” He looked at me closely for a long moment. “Of course you’ll be okay.”

I’m thinking about that talk with Sam, because he has a remarkable and seemingly unassailable faith in the order of things, but also because of the comfort I was able to take from it. My genetic family has not been a source of support for me, so I’ve found safety and community in other places, odd places.

The process of doing this while working for Hillel has been frustrating, joyful and confusing, a lot like how you might feel about family. We create identity through family-we decide who we are and who we are not, based on the structures and expectations around us. We decide whether or not we want to be part of the family, and what we need to do to make it a place we want to be in.

The point of all this rumination is to say that as long as I’m invested in Jewish communities, they will be the places where I’ll feel the most injured, the most vulnerable, and the most resourceful. As I’ve discussed in earlier posts, the boundaries that Jewish communities create define who is allowed in and who is out. It has to, that’s how you create community, not everyone can be a part of it. Ironically, though, while I attack these boundaries as exclusive and damaging, they have grown me, they’ve constructed my spiritual and moral backbone. Feeling injured has galvanized me, but the same isn’t true for everyone. While it’s led me to activism, it pushes others out the door.

My students over the years have been a feisty, creative, cynical, deeply thoughtful bunch of characters. I want them to exist and flourish inside of a community that they build, that welcomes them because of who they are instead of who they are not.

-Chanel Dubofsky

- No Comments

May 10, 2010 by admin

Looking Up

I spend a lot of time riding the bus. I prefer it to the subway, because you can see the city, and because it’s easier to read on the bus-it’s slower. So I am unhurried in getting to my destinations in the city, but impatient about the snail’s pace of making change in the world and in my communities. As one of my favorite students, as well as Walt Whitman, is fond of saying, “I am large, I contain multitudes.”

Doing any kind of social change work requires a certain level of optimism. It’s often hard to find reasons for it, and even hard to maintain those reasons when things get worse, or when it never stays good for very long. Optimism is not innate to my personality, but it has become essential to my activist life.

Two years ago, I attended a three day long training for Jewish educators with Keshet, a Boston based organization that works for the inclusion of LGBTQ Jews is all aspects of Jewish life. It was truly a restorative experience for me, to see folks from so many different Jewish organizations being challenged and given impactful tools to challenge others. The fact that I was encouraged to attend the training by Hillel was a source of great relief and pride for the organization I have worked for for years.

There are a lot of reasons to feel positive about change in the Jewish community: The ordination of gay and lesbian rabbis, the establishment of robust Jewish feminist spaces, the creation of new ritual, the funding and nurturing of organizations that work for real inclusion. The question remains as to the depth of the change we will be able to make, and what the cost of addressing change on a level of pure lip service will be. It’s not simply a matter of giving folks permission, of tolerance (oh, how I hate that word), it’s about changing a culture. We have to bring what is considered marginal into the mainstream, to take this as seriously as the charge to learn Torah, defend Israel and grow ourselves as a people.

The potential for change, when we are empowered to ask honest and provocative questions about the present and future state of our

communties, is truly stupendous. We have to be optimistic enough to believe that such a thing is possible.

–Chanel Dubofsky

- 2 Comments

May 3, 2010 by admin

With and Without (Part II)

It occurs to me sometimes that I spend a lot of energy pushing on doors that seem like they’ll never open. The doors, of course, lead to inclusive, feminist, actively anti racist, socio-economically diverse, queer positive Jewish communities

In my previous post, I spoke about feeling marginalized from Jewish communities because of a pressure to form a certain kind of family and to behave according to expectations prescribed to Jewish women. Here, I’d like to offer my own prescription for making change, not only to this specific paradigm, but also to challenge our larger “communal” values.

1. Challenge/Expand the definition of “family”

It’s not our fault as Jews that we’ve absorbed the idea of the nuclear family- we live in a society where that is the norm, but just because it’s something we’ve inherited doesn’t mean we can’t redefine it. Family does not simply mean a wife/mother, a husband/father and their biological child-it’s any combination of people who love and support each other. If we adopt this larger definition of family, if we actively discuss it, point it out to our children, create programming around it, make different kinds of families visible, then we no longer have to marginalize people who don’t fit into it or do not choose it.

2. Stop treating heterosexuality as the norm and the expectation.

It goes without saying that Jewish communities prize the heterosexual couple/ relationship over all others, and that we demand that queer Jewish folks fit into this model in order to be accepted. We have to teach about ally-ship the same way we teach Jewish text, mitzvot, history. Part of being a good and active ally is not assuming that everyone around you is straight, or talking about how straight you are, or how everyone must want what you want and be who you are. This is precisely the kind of behavior that makes it difficult to be our authentic selves in Jewish communities, and pushes us

away.

3. Publicly acknowledge people for accomplishments that have nothing to do with marriage/children

In Jewish communities, we value academic and artistic accomplishments–to the point where we invisibility those who lack access to the networks and institutions that provide these opportunities–but only to a certain degree. Continuity, in a traditional sense, is most explicitly valued. What if we created Jewish ritual and/or publicly acknowledged moments and accomplishments that have nothing to do with marriage or procreation? What if we named and placed value on our own moments of growth?

4. Understand that sexism hurts everyone.

Sexism impacts men as well as women, not to mention folks all along the gender spectrum. Placing oppressive gender roles upon women causes men to suffer as well. Based on what we’re socialized to believe about women, we expecte to see them as maternal, as primary care givers of children, even if they are partnered. On the other hand, we are leery of men who are kindergarten teachers and baby sitters, however, because they are stepping into a traditionally feminine role, rendering them “abnormal” and “dangerous.”

This is not different in Jewish communities, where we also mistrust, confine and punish men, in ways that are both glaring and insipid. We can break the cycle once again by opening the definition of what it means to be male and female in Jewish life, as well as exploring what lies between the gender binary. We cannot simply make overtures towards inclusivity, we must own it.

To some degree, Jewish communities can do all of the above. I believe this because I’ve seen communal change on many levels, and because I know people who are committed to making change and working for justice. I also believe that this is within me, both of these things, the rabble rouser and the person who wants to remain connected to Judaism. The potential of Jewish communities to be just and authentic is more than is being realized, and because this is true, we must pursue, claim and demonstrate new values. We know we can do better. We have no choice.

–Chanel Dubofsky

- No Comments

April 26, 2010 by admin

With and Without (Part 1)

At the heart of it all is a story that these days, I rarely tell. Most of the time, when I offer the stories of my past lives, they’re about my mother and grandmother, the resourceful, opinionated women who raised me. It was from them that I learned self determination and independence–feminism, actually, although I didn’t know the word for it until high school.

My mother’s life as a single woman was desperately difficult. She and my father divorced when I was seven, the same year she was diagnosed with the breast cancer that would kill her twelve years later. She was the lone provider in my house, and worried about money more than I will probably ever be able to comprehend. Looking back, I’m surprised she could sleep at night, knowing how much anxiety plagued her. She searched for safety and security, both within herself and within the world which she saw as consistently cruel and unstable.

I often wonder what she would think of my life now–31 years old, college educated, reasonably traveled, living in a big city, unmarried, yelling about gender politics, grappling with this concept of inevitability that seems to be everywhere around me. I was socialized to be outspoken, to have opinions, to believe I could do anything, but I was also expected to get married and have children. Once I told my grandmother that I wasn’t interested in either husbands or babies, and she said, “Oh, I didn’t want those things either, but then, you do it. You’ll change your mind.” It’s this idea–that as women, we will capitulate, whether it’s because we’ll realize that we want it, or because at some point, it will be impossible to avoid it, but either way, we will accept marriage and child rearing into our lives because that’s what happens. There are simply no other choices. It happens to everyone.

For me, honoring my mother means living a fuller life than she was able to. That means owning the privilege I have to be honest with myself, that I like being alone. It feeds my soul, it feels genuine to me. It’s hard for the Jewish community to hear that–because we remain entrenched in a sexist world where women don’t know what’s best for them, where they must be attached to a man to be see, because we as a Jewish people need women to perpetuate ourselves, because on a purely practical level, being alone is complicated and scary.

The pressure to couple and reproduce comes from everyone I know–my friends on J-Date, my friends who ask me about my relationships, my family members who make jokes about me being over thirty (!) and single, people to whom I speak about feminism, readers of my blog, my friends outside the Jewish community (I have some), media, etc. At the same time as I dismiss questions about wanting to meet someone, inquiries into my sexuality, the obvious ratios of single men to single women at parties or meals, it hurts. What this persistent questioning and marketing whether it comes from inside the Jewish community or out, says is “You are not enough, no matter what you think.”

It hurts me the most when it comes from inside the Jewish community. As long as I remain single, comfortable and true to myself, I will never be a full member of many Jewish communities. No matter how fervently I love Judaism and Jewish communities, the truth is that if I do not produce Jewish children, I will always be thought of as on the margins.

“The Jewish community,” as if there were such a monolith, has a responsibility to listen, and to hear, it’s not just theoretical, it’s in the daily liturgy-three times. We might listen, but what truths will we really hear? Only those that make us feel good? Only those that we consider to be valid or real? When will we listen to each other and value what we hear? When will we welcome our whole selves and our realities in, instead of insisting that we change to accomodate comfort?

As women, admitting to ourselves what we want and don’t want is like dropping a raw egg from a height and watching it break, the yolk spreading everywhere, messy, unwieldy, impossible to tidy. Telling our own truths has the power to level our daily lives and the lives of those around us, but no matter what, we have to tell them, live them, and work to build communities that value them. In the words

of Muriel Rukeyeser, “What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life? The world would split open.”

–Chanel Dubofsky

- 1 Comment

Please wait...

Please wait...