by Chanel Dubofsky

“I Wanted to Be Pat Boone’s Daughter.”

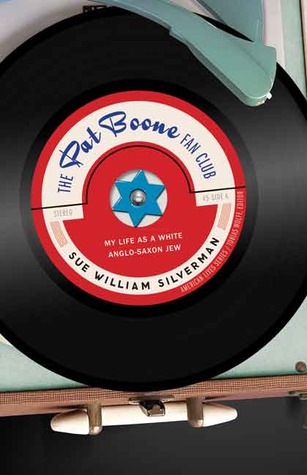

When Sue William Silverman and I met to discuss her new memoir, The Pat Boone Fan Club: My Life as a White Anglo Saxon Jew, she played “Exodus” for me on her iPhone. (Boone actually wrote the lyrics for the theme song for the movie Exodus, which lyrics he titled “This Land Is Mine.”)

Me: It sounds really…generic.

Sue William Silverman: Everything about Pat Boone is generic. That’s why I loved him, I could make him into anyone I wanted him to be.

Silverman’s memoir is a story of among other things, evolving identity, of wishing your reality wasn’t yours in the most profound way, of doing whatever it takes to escape it and become yourself.

Lilith: The Pat Boone Fan Club opens with a quote from James Baldwin:

“Identity would seem to be the garment with which one covers the nakedness of the self: in which case, it is best that the garment be loose, a little like the robes of the desert, through which one’s nakedness can always be felt, and, sometimes, discerned. This trust in one’s nakedness is all that gives one the power to change one’s robes.”

Can you comment on why you include this?

Sue Silverman: To me, this quote conveys the complexity of identity, which is what I explore in the book. How, when, and why do we change our identity? What parts of ourselves do we reveal?

For me, growing up in a troubled, incestuous family, I lost a sense of my true self, including a sense of my Judaism. Throughout the book, I tumble through various identities: I tried to pass as Christian; I tried being a kibbutznik, picking apricots in Israel; as a hippie, I tramped cross-country in a VW camper; I vacationed in Yugoslavia with a boyfriend who, it turned out, was anti-Semitic; I married – and divorced – two Christian men.

More than anything – and this is the heart of the book – I wanted to be Pat Boone’s daughter. I wanted that very Christian, squeaky-clean 1960s pop star to adopt me. Why? Because my father sexually molested me growing up.

But why Pat Boone? For hours, as a young girl, I gazed at photos of him and his beaming, golden family in fan magazines. If Pat Boone could raise four daughters, couldn’t he raise me, too? In my child-mind, he was the ideal of what a father should be: someone nurturing, caring, safe.

So the identity I most wanted was that of Pat Boone’s fifth daughter!

In short, I was a bobby soxer, a hippie, a wanna-be Christian girl, a rebel. It’s one of the paradoxes of the book that I was all of those things, yet none of them was my core self.

If your family is troubled, the natural tendency is to seek identity and comfort elsewhere. In this way, I hope that others will relate to my story. Obviously, everyone is going to have a different ideal image upon which they can project their hopes and desires. For years, mine happened to look like Pat Boone!

Lilith: This book is about young women, sexuality, being the “right” kind of girl, female identity, reclamation of power, etc. Of course, that’s essential and innate to your story, but what do you think about the idea that this is a feminist book?

SS: I am a feminist, and I love that you see The Pat Boone Fan Club as a feminist book! Girls, maybe particularly baby boomers (and previous generations), were offered few positive and empowering roles growing up. There were the “good” chaste girls, or there were the so-called “bad” girls, meaning they had pre-marital sex.

The harm of growing up with rigid stereotypes is what I particularly try to convey in the section, ironically entitled, “The Endless Possibilities of Youth.” It wasn’t until my generation reached college, when we became hippies and overthrew the old paradigm, that we began to rid ourselves of those preconceptions.

I also feel my story reflects that of girls raised in families who were told, to their detriment, to keep secrets. I don’t just mean girls who were sexually molested. Girls traditionally have generally had little or no voice. Now, by writing, by speaking my truth, I’ve tried to break through those negative messages with which we were raised.

I wrote two previous memoirs: one about growing up in my incestuous family, the other about a subsequent sexual addiction resulting from the incest. Writing those books was also part and parcel of my own growing awareness of feminism. I learned that women can speak out, that our voices must be heard, even if that makes the male power structure uncomfortable!

I feel very fortunate that I have a voice and that I can speak for other women who, scared, remain silent. I receive many e-mails from women thanking me, in effect, for telling their story, too.

Lilith: How has writing this book had an impact on the Jewish identity you have now?

SS: Ultimately, it’s made me feel more Jewish – not in the religious sense, I’m not observant – but in the sense of embracing my heritage. I am Jewish. In the end, I didn’t become Christian, and Pat Boone (big surprise) didn’t adopt me.

What I discovered by writing this book is that, for years, yes, I felt conflicted about my Jewish identity. I’d lost my way. But now, by writing about the past, by speaking out, I feel closer to my tribe. When I was a girl and a young woman, I felt abandoned by my Jewish family who couldn’t keep me safe and, by extension, I felt abandoned by the larger community. As a wounded girl, I didn’t know how to ask for help, and so felt isolated. But now I give talks to Jewish organizations and feel more embraced…and heard.

Lilith: Have you read Nathan Englander’s story, “What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank“? There’s a conversation in there about, if the Holocaust came again, who would hide them. It made me think a lot about your relationship with Pat Boone and how at the end of the book, you confront him about his politics. He’s made whole in a way, real.

SS: First let me say that I’m glad you think I make Pat Boone seem real, whole. At the heart of the book are three actual positive encounters I had with him, one, as a New Jersey teenager when I attended his TV show, “The Pat Boone Chevy Show,” in Manhattan. Back then, I was so blown away by his presence that, when I got his autograph after the show, I was too overwhelmed to speak. Yet, in my child fantasies of him, I always felt safer with him than with my family.

Then, in 2003, he happened to be giving a concert close to where I live. I attended. Uninvited, I barged backstage afterward to tell him what he meant to me growing up. I told him about my father and about how he, Pat Boone, offered hope. He sympathetically listened to me – even though he obviously had no idea who I was!

Subsequently, he invited me to meet with him again to have a “real” conversation. I did. (After a Christmas concert of his, of all things!) I was wearing a jacket with an embroidered flower on it and, pointing to it, and referring to my childhood, he said that I “reminded him of a flower growing up through concrete.” He had seen me! He heard my voice – unlike my real father! Ironically, this was all I really needed from him. I was now able to move forward and discover my own true self…who is, yes, a Jewish self.

Additionally, I describe how Pat Boone wrote the lyrics to the song “Exodus.” As part of his religion, ironically, he calls himself an “adopted Jew” because, he says, “everything we hold sacred as Christians has come out of biblical Judaism.” So if there were another Holocaust, I’m quite certain Pat Boone would hide Jews. That said, sure, I wish his American politics were as liberal as mine. But there’s nothing I can do about that.

Lilith: The Pat Boone Fan Club really pushes the reader to engage with the idea and practice of being an imposter, of needing and trying (and sometimes succeeding) to successfully pass. It feels like a very Jewish narrative in some ways.

SS: The idea of being an imposter is interesting. I have Jewish friends who have had nose bobs, or tried in other ways to look more Christian. I also have relatives who Americanized their last names in the belief they’d be more successful in their careers.

Of course there were – and are – tangible reasons for this. I grew up in a time when some colleges still had quotas on the number of Jews they would accept. Likewise, housing subdivisions once had restrictive covenants to keep Jews out – as well as African Americans, and Latinos, and anyone else considered “other.” Anti-Semitism has always existed, so there are always incentives to pass.

As much as I myself once wanted to pass…I now just as much don’t want to. One thing I most admire about Jewish values is how, as a group, we stand against injustice and discrimination. Jews played a crucial role in the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, and many different Jewish organizations focus on all sorts of civil and human rights problems, worldwide. I feel it’s in our DNA to do so, whether the human rights violations are overseas, or happening to little Jewish girls, in unsafe families, right here at home.