The Lilith Blog

October 21, 2015 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

A Novel About How Blogs Have Changed Our Lives

There are approximately over 152 million blogs on the Internet and incredible as it may seem, more blogs are going up all the time. In fact, a new blog is created somewhere in the world every half a second, which, if you do the math, means that 172,800 blogs are added to the Internet every day. So is it any wonder that the art and science of blogging has worked its way into the pages of contemporary literature?

There are approximately over 152 million blogs on the Internet and incredible as it may seem, more blogs are going up all the time. In fact, a new blog is created somewhere in the world every half a second, which, if you do the math, means that 172,800 blogs are added to the Internet every day. So is it any wonder that the art and science of blogging has worked its way into the pages of contemporary literature?

The Good Neighbor (Griffin Books, October 2015), Amy Sue Nathan’s second and latest novel, introduces us to Izzy Lane, Jewish, recently divorced and still reeling from the break-up of her marriage. The newly single mom moves back to the Philadelphia home she grew up in, five-year-old Noah in tow. On a whim, she starts a blog and with the help of her close friends—and her elderly neighbor, Mrs. Feldman—begins to feel like she’s stepping closer to her new normal. Until her ex-husband shows up with his girlfriend. That’s when Izzy invents a boyfriend of her own.

Blogging about her “new guy” provides Izzy with a way to entertain herself Noah’s asleep. After all, what’s the harm, right? But then her blog soars in popularity and she’s given the opportunity to moonlight as an online dating expert. How can she turn it down? Soon everyone want to meet the mysterious “Mac,” someone online suspects Izzy’s a fraud, and a there’s a new, real-life guy who seems pretty interesting. Nathan’s sharp-eyed look at how the blog culture has changed our lives is a smart, stylish read; here’s an excerpt below.

- No Comments

October 20, 2015 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Ethel Rosenberg Reimagined in “The Hours Count”

Although it’s been more than 60 years since Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were executed, their horrifying story still has a powerful hold on the public imagination. As recently as August, 2015, the two sons of the couple wrote an Op-Ed piece in the New York Times that concluded with these words:

Although it’s been more than 60 years since Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were executed, their horrifying story still has a powerful hold on the public imagination. As recently as August, 2015, the two sons of the couple wrote an Op-Ed piece in the New York Times that concluded with these words:

Our mother was not a spy. The government held her life hostage to coerce our father to talk, and when that failed, it extracted false statements to secure her wrongful execution. The apparent rationale for such action—that national security demanded it during a time of international crisis—has disturbing implications in post-9/11 America. It is never too late to correct an egregious injustice. We call on the government to formally exonerate Ethel Rosenberg.

And now there is the publication of The Hours Count, a novel that focuses squarely on the last five years in the life of Ethel Rosenberg. Author Jillian Cantor hewed closely to the facts, but added several fictional characters, including a neighbor, Millie Stein, her Russian husband Ed and her son, David, who at age three is still not talking. Millie is the lens through which we are able to view Ethel in a wholly unexpected way: as wife, mother and friend. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough talked to Cantor about why she chose to write Ethel’s story and how she was able to blend the factual with the fictional.

YZM: What drew you to the subject of Ethel Rosenberg?

JC: I came across the last letter Ethel (and Julius) wrote to their sons in an anthology of women’s letters that I’d checked out of the library. One of the last things they wrote is for their sons to always remember that their parents were innocent. Before I read this, I hadn’t thought of Ethel as a mother (her sons were six and 10 when she was executed – very similar to the ages of my own sons) or even as potentially innocent. So I did a little research, and I began to believe that she might actually have been innocent. I wanted to reimagine her as a mother, as a woman who was unjustly taken from her family.

- No Comments

October 19, 2015 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

From the Lilith Slush Pile to a Sarah Silverman Film Deal

Ever since I discovered the work of Amy Koppelman winking up at me from Lilith’s slush pile I’ve kept her on our radar. We published her short fiction a few years ago. She’s a novelist of astonishing depth and power, with a dark and haunting voice that is both lyrical and fearless. The rest of the world seems now to agree, as the film based on her novel I Smile Back, starring—yes—Sarah Silverman in a dramatic role, opens commercially later this month after being received enthusiastically at Sundance.

Ever since I discovered the work of Amy Koppelman winking up at me from Lilith’s slush pile I’ve kept her on our radar. We published her short fiction a few years ago. She’s a novelist of astonishing depth and power, with a dark and haunting voice that is both lyrical and fearless. The rest of the world seems now to agree, as the film based on her novel I Smile Back, starring—yes—Sarah Silverman in a dramatic role, opens commercially later this month after being received enthusiastically at Sundance.

In her new novel, Hesitation Wounds, Koppleman introduces us to Dr. Susanna Seliger, a renowned psychiatrist who specializes in treatment-resistant depression. Skilled and compassionate, Susa is always ready to discuss treatment options, medication, and symptom management but draws the line at engaging with feelings. Her own damaged past is made present by one patient, Jim, whose struggles tear her open, revealing her latent guilt that she could have saved the people she’s lost, especially her adored, cool, talented graffiti-artist brother. Spectacularly original, gorgeously unsettling, Hesitation Wounds is a novel that will sink deep and remain—like a persistent scar or a dangerous glow-in-the-dark memory.

In her new novel, Hesitation Wounds, Koppleman introduces us to Dr. Susanna Seliger, a renowned psychiatrist who specializes in treatment-resistant depression. Skilled and compassionate, Susa is always ready to discuss treatment options, medication, and symptom management but draws the line at engaging with feelings. Her own damaged past is made present by one patient, Jim, whose struggles tear her open, revealing her latent guilt that she could have saved the people she’s lost, especially her adored, cool, talented graffiti-artist brother. Spectacularly original, gorgeously unsettling, Hesitation Wounds is a novel that will sink deep and remain—like a persistent scar or a dangerous glow-in-the-dark memory.

- No Comments

October 13, 2015 by Pamela Rafalow Grossman

“Very Semi-Serious”: New Yorker Cartoonists in a New Film

“Can I come back?” asks cartoonist Liana Finck of Bob Mankoff, longtime cartoonist for—and now cartoon editor of—The New Yorker.

“Can I come back?” asks cartoonist Liana Finck of Bob Mankoff, longtime cartoonist for—and now cartoon editor of—The New Yorker.

Finck has brought some of her work to Mankoff’s office at the magazine, and received thoughtful feedback but not the break-in acceptance she was hoping for. It’s a sweet and poignant moment in director Leah Wolchok’s documentary Very Semi-Serious, which chronicles New Yorker cartoonists past and present and the process by which Mankoff makes his selections. In Finck’s words are reflected a near-universal hope for success and an equally commonplace fear of rejection. The warm and thoughtful film is filled with such touching, relatable and, unsurprisingly, funny moments. It had its world premiere in April of 2015 at the Tribeca Film Festival (where it was announced that 33% of the festival’s feature filmmakers this year were women, the highest percentage in its 14-year history) and will be shown on HBO starting December 7th after a brief theatrical run.

Finck is a former Lilith intern whose work has been appearing regularly here since she was in high school—and she did keep trying with The New Yorker, eventually landing several cartoons there. On October 2, Finck and New Yorker cartoonists Mort Gerberg and Emily Flake, along with Mankoff, took part in a panel discussion after the film, moderated by widely adored New Yorker cartooning fixture Roz Chast, part of the annual New Yorker Festival. (Chast’s interview moments in the film are often laugh-out-loud hilarious—as when she explains that she prefers indoor settings to venturing out: “The temperature’s never right—it’s too hot, it’s too cold, it’s too sunny, it’s too rainy…there are branches!” And who knew she had a collection of vintage cans?) The fact that three of the five people onstage for the panel were women reflects the deliberate efforts The New Yorker has made, under editor David Remnick, to break out of the old-boys’-club mold.

- No Comments

October 12, 2015 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

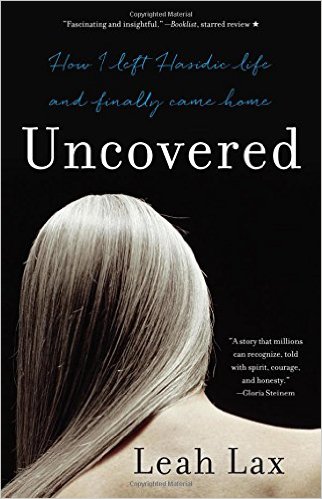

“I Am No Victim”: Leah Lax on Living and Leaving Her Hasidic Life

Leah Lax is familiar to Lilith readers for several of her essays in the magazine, most recently the economically told life history “One Woman’s Resume.” Raised in a Reform Jewish family in Dallas, close to her immigrant grandparents, who still ate schmaltz herring in their elegant nouveau-riche home; she says that growing up, she learned to crochet and ride a horse. In her teens she left this life—and her neglectful parents—to become a Lubavitcher Hasid, and soon after entered into an arranged marriage. Like the others in her community, she did not own a television, read secular books, surf the Net or go to movies or restaurants. Then after nearly 30 years—and seven children—she left that cloistered life behind. Her memoir, Uncovered: How I Left Hasidic Life and Finally Came Home, charts the years she gave over to strict observance of religious law, from hair covering to the order of putting on one’s shoe in the morning, from compulsive pre-Passover cleaning to relinquishing all questioning. It also reveals the secrets she harbored behind the observant façade, and the sprouting of a feminist consciousness as she came to know herself. She talks to fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about her life beneath the wig—and what it was like to emerge from it, uncovered, after so long.

Leah Lax is familiar to Lilith readers for several of her essays in the magazine, most recently the economically told life history “One Woman’s Resume.” Raised in a Reform Jewish family in Dallas, close to her immigrant grandparents, who still ate schmaltz herring in their elegant nouveau-riche home; she says that growing up, she learned to crochet and ride a horse. In her teens she left this life—and her neglectful parents—to become a Lubavitcher Hasid, and soon after entered into an arranged marriage. Like the others in her community, she did not own a television, read secular books, surf the Net or go to movies or restaurants. Then after nearly 30 years—and seven children—she left that cloistered life behind. Her memoir, Uncovered: How I Left Hasidic Life and Finally Came Home, charts the years she gave over to strict observance of religious law, from hair covering to the order of putting on one’s shoe in the morning, from compulsive pre-Passover cleaning to relinquishing all questioning. It also reveals the secrets she harbored behind the observant façade, and the sprouting of a feminist consciousness as she came to know herself. She talks to fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about her life beneath the wig—and what it was like to emerge from it, uncovered, after so long.

YZM: What drew you initially to Hasidic life?

LL: At first: their raw wordless melodies, the mysteries they said were hovering between the lines of our incredible texts, and the intimation that somehow this is me, too, since I was born a Jew, so that it seemed they were offering new self-discovery. I was 16—I think that alone explains a lot.

Then came Hasidic offers of the sublime, and assertions that they owned a huge Truth so old and vast it shut my small mouth, coupled with my weak will and my need to please.

If I dig, I always see more: the homoerotic quality of Hasidic life, and their promise that, if I followed the rules, I’d always feel I belonged, something I had always craved.

YZM: Was Hasidic life sustaining for a time?

LL: It was. I was barely 17 when I left my family, and received no subsequent financial support from them. Of course, I went straight to university on full scholarship and could have simply immersed myself there and grown up for a few years, but still, the Lubavitchers I had met gave me a sense of family, adult concern for my young life, structure, someone other than my damaged family to identify with, a place to go on weekends. They meant a lot.

- No Comments

October 7, 2015 by Eleanor J. Bader

Rape in the Middle East and Women-Led Organizing: Is Social Change on the Horizon for Syrian Refugees?

As desperate refugees continue to stream into Europe in response to the Syrian Civil War and ISIS brutality, it’s easy to become overwhelmed or grief-stricken. But Yifat Susskind, sees a modicum of progressive social change on the horizon for those most affected by the crisis.

© Maureen Drennan

Susskind, Executive Director of MADRE, a 32-year-old women’s human rights organization, is chatting with me in MADRE’s Manhattan office, moving between her personal history as an Israeli-born kibbutznik and the horrors facing women in war-torn areas the world over. Then, she matter-of-factly mentions something shocking. “So many women have been sexually abused by ISIS that it is possible to overturn the social norms that rape survivors in the region often experience,” she goes on. “The idea that rape is the woman’s fault falls apart when it is happening to everyone. As a result, women who have been raped are no longer seen as damaged goods, but are instead being hailed as returning prisoners of war who need to be reintegrated as heroes.”

It’s an amazing turn, but Susskind makes clear that this kind of shift is not anomalous, just little known. What’s more, it is not the only sea change being ignored by mainstream media. Indeed, she reports that there is a great deal of organizing going on in improbable places, much of it women-led.

To Wit: Over its three decade history, MADRE –“mother” in Spanish – has partnered with women’s groups in Colombia, Guatemala, Haiti, Iraq, Kenya, Nicaragua, Palestine and Syria. Their efforts are two-pronged: Raising money for organizations providing hands-on social services and advocating for policies that benefit women, girls and families affected by violence.

© Meena Lenn

In Colombia, this has meant pairing with Taller de Vida, a group that provides art therapy and trauma counseling to former child soldiers. In Guatemala, MADRE has worked with a women’s weaving collective to help preserve a traditional art form and raise money for low-income communities. In Kenya, they’ve joined with the Indigenous Information Network to teach women how to preserve food and collect rain water in areas suffering through drought and severe climate change. And in Iraq they’ve helped support a Women’s Peace Farm for female agricultural workers displaced by war. With the Organization for Women’s Freedom in Iraq [OWFI] they have created an underground railroad for girls and women fleeing ISIS-controlled areas and have raised funds to establish a safe house for them. In the West Bank their work has involved supporting Midwives for Peace to ensure better birth outcomes and improved maternal health in that sorely underserved area.

Since 1983 MADRE has raised about $31 million for these and other projects. Right now, Susskind says, they’re coordinating fundraising for the creation of a rape crisis center and shelter in Kurdistan, to serve women and girls fleeing sexual slavery as well as LGBTQ Iraqis who, she says, “are especially threatened in this super-reactionary climate.” Once the goal of $150,000 is reached–they are hoping for late fall–the center will open its doors. “Many of the women and girls who will use the shelter have nowhere else to go,” Susskind explains. “Their families have been killed and they need immediate medical and psychological help in order to heal.”

© MADRE

Still, while Susskind values direct service, she is pleased that the center will also promote political activism, including support for a campaign to overturn a prohibition on privately run shelters for survivors of domestic abuse. “Right now the Iraqi government does not allow women’s groups to run residences for battered women. Those that disobey are frequently raided by police. If they were allowed to operate openly, the raids would stop,” she says. In addition, under current law, an Iraqi woman needs her husband’s consent to obtain an ID card. Without this document, she is ineligible for food rations and housing. Not surprisingly, MADRE has joined with OWFI and other organizations to push for an end to this policy.

They’re up against mighty foes, both religious and secular, but organizing as women for women is incredibly powerful, Susskind says. “When we mobilize as mothers, it means we’re prioritizing the needs of the most vulnerable people. If we can get governments to focus on these groups, whether in terms of economics, war, or nuclear proliferation, we’ll be a lot closer to what we want to see in the world.”

Susskind herself is the mother of two boys and has been at MADRE since 1997 and executive director of the organization since 2011. “I was born in 1967 on a kibbutz near the Lebanese border,” she tells me. “My paternal grandparents founded the kibbutz in the 1930s and my dad was born in 1948, the year Israel was created. They were the quintessential Jewish family: Ashkenazi, secular and Zionist.”

Her American-born mother’s history stands in stark contrast. Nonetheless, here too Susskind was exposed to political ideas at an early age. She describes her Russian-born maternal grandmother as typical of early 20th-century Jewish immigrants: A socialist, atheist, union supporter who worked in the garment industry.

“My mother’s mother taught me about Jewish ethical practice,” she says. “It was from her that I learned that to be Jewish is to be part of an historical continuum. She taught me to honor the visionary people who came before me, whether they were abolitionist Quakers, pacifist World War I opponents, or Jewish trade unionists.”

In fact, Susskind sees her work at MADRE as ensuring the historical continuity of oppositional politics. “Right after I finished college I went to Jerusalem to organize support for ending the occupation,” she says. This introduced her to joint Israeli-Palestinian human rights groups as well as Women in Black. She did this work for six years and returned to the US in 1997.

Does the work ever get you down? I ask, wondering how she and her co-workers stay sane in the face of so many atrocities. Susskind takes a minute and smiles widely before continuing. “There is great joy in this work because it is fundamentally about making things better,” she says before pausing. “I’m not at all religious but the Jewish teaching that we are in partnership with creation resonates with me. So does a statement attributed to [Mishnah sage] Rabbi Tarfon: ‘It is not incumbent upon you to complete the work, but neither are you at liberty to desist from it.’”

After this brief nod to the Pirkae Avot, Susskind turns to the pile of papers on her desk. “The work will not be finished in my lifetime,” she shrugs, “but I will do as much as I can to promote peace and justice.”

- No Comments

September 24, 2015 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Jewish Thrifting

I’m on high alert even before I walk through the door, fully charged and primed for action. For the next couple of hours, I will ignore phone calls, texts and emails, morphing into the Bionic Woman, with no need to sit, eat, drink or use the restroom. I am about to embark on what for me is a quasi-scared endeavor: pawing through the schmattes in the National Council of Jewish Women’s thrift shop on East 84th Street in NYC. I love thrift shops of all denominations, but as a Jewish woman, I derive a certain extra bit of nachas from the thrift shops run, and frequented by and most essential of all, donated to by my foremothers, the women of my tribe.

I make these visits with some regularity and with the exception of socks, pantyhose and underwear, depend on them to purchase all of my clothing. I buy nothing new. Why should I? Sadie, Mollie, Esther and Bunny and their pals have already provided me with everything I ever wanted—and more. A long, black cashmere coat from Saks, an Ungaro jacket in maroon quilted velvet, a heavily encrusted purple silk skirt, all beading and sequins, from Ralph Lauren—these are only a few of my thrift shop finds.

There are practical reasons to switch to thrifting: it’s economical and allows me to afford clothes that I would otherwise only dream of. And I believe we have an almost moral imperative to buy secondhand: there is too much stuff in the world and we have an obligation to reuse it.

But even without these incentives, I would still be a Second Hand Rose, for reasons that are less quantifiable but every bit—at least to me—compelling. I feel strange kind of tenderness and pity for all the abandoned and discarded garments, and am endlessly curious about their former owners. Who bought those wide black pants trimmed in feathers and where did she go in them? That pleated navy jumpsuit with the gold trim? The powder blue suede miniskirt? Each has a story to tell and oh, what a story it must be. In my imagining those stories, it’s as if I have been able to resurrect not just the garments, but the women who wore them.

I should add here that I come from a venerable line of thrifters. My mother had the bug, and so did my grandmother, Tania. Well into her eighties, Tania worked as a volunteer at the thrift shop of a Jewish charity in Miami when Collins Avenue and Lincoln Road were still the province of elderly, Ashkenazi Jews who traded the harsh winters of the north and east—in my grandmother’s case, it had been Detroit—for the sunny climes of Southern Florida. My grandmother traveled an hour by bus to get to this thrift shop, and she was given advance pick of the donated merchandise, which is how I came to own the exquisite silk scarf with the lush pink and coral flowers splattered all over it. The name Hermès meant nothing to Tania, but she had a keen eye and the heavy silk, glorious pattern, and hand rolled edges spoke to her of quality. “I thought you would like it,” she said. “And if you didn’t, that was okay too—it only cost $2.50.”

But to get back to the National Council thrift shop, its cousin, the Chai Thrift in Brooklyn, and that wonderful synagogue thrift shop on Long Island, whose name and town elude me now, though I can still tell you what I found there. Here are my roots, here are my people. The ladies, like my grandmother, may now be gone. But what they gathered and cherished, their cunningly styled evening bags, fur coats, palazzo pants and cocktail dresses, represent a group portrait, a patient construction of self that continues to live on, at least for those of us with the eyes to discern it.

- No Comments

September 21, 2015 by Helene Meyers

Holy and Unholy Tweets

The upcoming week is a sacred one for both Jews and Muslims. Tuesday night ushers in Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement that is the climax of the 10 Days of Awe and is the holiest day of the Jewish year. Traditional Yom Kippur observances include a full day of fasting followed by communal break-the-fast meals. Many congregations run food drives to assuage the hunger in their communities that is neither voluntary nor holy.

Wednesday night ushers in Eid al-Adha, the 4-day Festival of Sacrifice that marks the willingness of Ibrahim to sacrifice Ishmael and God’s ultimate substitution of a sheep for the son that was a gift to Ibrahim (the Jewish version of this story is known as the Binding of Isaac). Eid al-Adha marks the end of the Haj, the pilgrimage to Mecca that observant Muslims are required to make at least once in their lifetime if they are able; observances of Eid al-Adha, also known as the Greater Eid, include communal meals, the exchange of gifts, and donations to the poor.

This close proximity of Jewish and Muslim holy days is a welcome counter to the close proximity of bigotry that has plagued Jews and Muslims during this past week. On Tuesday, in Irving, Texas, Ahmed Mohamed, an intellectually ambitious and adventurous ninth-grader, was taken into police custody for bringing to school a clock that he had made; the clock, a sign of his inventiveness and smarts, was mistaken for a device of terror. Despite official denials, Ahmed’s Muslim heritage and his name surely contributed to the decision to handcuff first and ask questions later. Displaying an ability to serve as educator-in-chief and to use social media for the common good, President Obama tweeted “Cool clock, Ahmed. Want to bring it to the White House? We should inspire more kids like you to like science. It’s what makes America great.”

On Wednesday, Ann Coulter, one of our chief provocateurs for the common bad, was nonplussed by the support for Israel expressed by several Republican candidates toward the end of the debate on September 16th. Shocking even those of us who are acutely aware of diverse forms of contemporary anti-Semitism, she tweeted “How many f—ing Jews do these people think there are in the United States?” Of course, the Jewish tradition of responding to insult with humor became general across the Twitterverse. Referring to the missing letters in “f—ing,” Yair Rosenberg usefully noted, “The best part of this tweet is how Ann Coulter censored the language to avoid offending people.” AJ Jacobs matched stats from the Kinsey Institute on sexual activity with Jewish demographic info to compute how many Jews have fornicated in the last month and how many were likely doing so while Coulter was tweeting.

Less funny was the unambiguous hatred that proliferated in replies to her tweet and with the hashtag #IStandwithAnn. These tweets ranged from “the Jewish community does not care about Americans” to resurrected charges of deicide to a hideous image titled “Swindlers List,” which featured a photo of Obama framed by a black star of David overlaid with the words “Rothchild’s Choice”; photos of Jewish male staffers (e.g., Rahm Emanuel, Larry Summers) are positioned at each point of the star. Coulter, like officials in Irving, Texas, went into denial mode. Notably, she tried to deflect any anti-Jewish meaning to her tweet by ascribing anti-Semitism to Hispanics and Mexican immigrants, a.k.a. “foreigners.”

My favorite answer to Coulter’s f—ing question came from Jennifer Weiner, who tweeted “You’re about to hear from all of them.” May 5776 be a year when all Jewish feminists are heard from, when we say “no” to anti-Semitism and Islamophobia, when we say “no” to those who use social media to play pernicious games of divide and conquer. May 5776 be a year when we say “yes” to the hard but necessary work of building and sustaining progressive alliances across ethnic, racial, and religious fault lines. May our 140 character messages and our longer-play writing help us to connect diverse religious and secular traditions that might make for a more peaceful world. Shanah Tovah and Eid Mubarak.

Helene Meyers is Professor of English and McManis University Chair at Southwestern University. You can follow her at @helene_meyers

- No Comments

September 16, 2015 by admin

End-of-Year/Start-of-Year Improvements

During these Days of Awe (and contemplation), here is some reading we hope will guide your introspection and prepare you for the new year.

- No Comments

September 10, 2015 by Pamela S. Nadell

Challenging Sexist Conversion Practices

Still from “A Tale of a Woman and a Robe”

Even before Jews around the world began reeling from the scandalous case of Barry Freundel, an Orthodox rabbi in Washington D.C. who frequently and secretly videotaped women immersing naked in the mikvah, the ritual bath next to his synagogue, a bold Orthodox independent filmmaker, Nurit Jacobs-Yinon, was trumpeting exposing in Israel another case of abuse of rabbinic power and the mikvah. Five years ago, she was stunned to see an ad seeking religious men to serve as a Beit Din, the court of three required to certify conversions at the mikvah. An Israeli feminist, Jacobs-Yinon knew little about what women faced as they went through conversion’s final step of ritual immersion. But with Israeli law making it impossible for immigrants, like those from the former Soviet Union, to marry unless they could prove Jewish descent on their mother’s side or undergo conversion, she realized the significance of this issue even for secular Israelis. An estimated 75 percent of converts are female, and typically those certifying their mikvah immersion are male.

What Jacobs-Yinon discovered about the violation of female converts’ dignity and modesty as the women, covered only by a robe, immersed before the men shocked and angered her. It led her to make “A Tale of a Woman and a Robe: Ritual Immersion of Female Converts” and to invitations to testify in the Knesset.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...