by Yona Zeldis McDonough

“I Am No Victim”: Leah Lax on Living and Leaving Her Hasidic Life

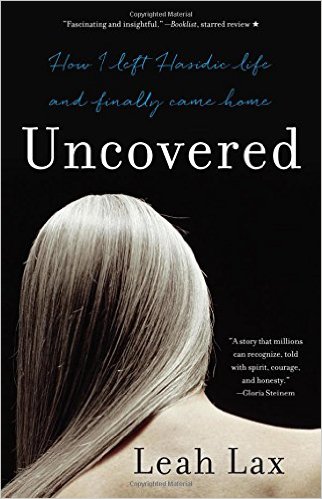

Leah Lax is familiar to Lilith readers for several of her essays in the magazine, most recently the economically told life history “One Woman’s Resume.” Raised in a Reform Jewish family in Dallas, close to her immigrant grandparents, who still ate schmaltz herring in their elegant nouveau-riche home; she says that growing up, she learned to crochet and ride a horse. In her teens she left this life—and her neglectful parents—to become a Lubavitcher Hasid, and soon after entered into an arranged marriage. Like the others in her community, she did not own a television, read secular books, surf the Net or go to movies or restaurants. Then after nearly 30 years—and seven children—she left that cloistered life behind. Her memoir, Uncovered: How I Left Hasidic Life and Finally Came Home, charts the years she gave over to strict observance of religious law, from hair covering to the order of putting on one’s shoe in the morning, from compulsive pre-Passover cleaning to relinquishing all questioning. It also reveals the secrets she harbored behind the observant façade, and the sprouting of a feminist consciousness as she came to know herself. She talks to fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about her life beneath the wig—and what it was like to emerge from it, uncovered, after so long.

Leah Lax is familiar to Lilith readers for several of her essays in the magazine, most recently the economically told life history “One Woman’s Resume.” Raised in a Reform Jewish family in Dallas, close to her immigrant grandparents, who still ate schmaltz herring in their elegant nouveau-riche home; she says that growing up, she learned to crochet and ride a horse. In her teens she left this life—and her neglectful parents—to become a Lubavitcher Hasid, and soon after entered into an arranged marriage. Like the others in her community, she did not own a television, read secular books, surf the Net or go to movies or restaurants. Then after nearly 30 years—and seven children—she left that cloistered life behind. Her memoir, Uncovered: How I Left Hasidic Life and Finally Came Home, charts the years she gave over to strict observance of religious law, from hair covering to the order of putting on one’s shoe in the morning, from compulsive pre-Passover cleaning to relinquishing all questioning. It also reveals the secrets she harbored behind the observant façade, and the sprouting of a feminist consciousness as she came to know herself. She talks to fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about her life beneath the wig—and what it was like to emerge from it, uncovered, after so long.

YZM: What drew you initially to Hasidic life?

LL: At first: their raw wordless melodies, the mysteries they said were hovering between the lines of our incredible texts, and the intimation that somehow this is me, too, since I was born a Jew, so that it seemed they were offering new self-discovery. I was 16—I think that alone explains a lot.

Then came Hasidic offers of the sublime, and assertions that they owned a huge Truth so old and vast it shut my small mouth, coupled with my weak will and my need to please.

If I dig, I always see more: the homoerotic quality of Hasidic life, and their promise that, if I followed the rules, I’d always feel I belonged, something I had always craved.

YZM: Was Hasidic life sustaining for a time?

LL: It was. I was barely 17 when I left my family, and received no subsequent financial support from them. Of course, I went straight to university on full scholarship and could have simply immersed myself there and grown up for a few years, but still, the Lubavitchers I had met gave me a sense of family, adult concern for my young life, structure, someone other than my damaged family to identify with, a place to go on weekends. They meant a lot.

YZM: When did that sense of belonging change?

LL: There wasn’t one specific point of change. In Writing a Woman’s Life, Carolyn Heilbrun explains that the conventional shape of a narrative too often doesn’t fit a woman’s story. We’re accustomed to a “hero” who is acted upon, makes a decision, and acts in response, and changes in the process. But when you give your life to others, when what you think and feel is pretty irrelevant before the booming voice of community, husband, Jewish law, you don’t make decisions and act, so you don’t change. Much. Instead, you swallow.

So how could I even write this memoir? When did Hasidic life change, when did I change? I could only recount key moments that sparked inner change and let you watch the non-action until you want to throttle her (me), until the cup finally spills over.

YZM: You tackle subjects that are usually taboo in the religious community: abortion, child abuse, homosexuality. Was it difficult to present such subjects on the page?

LL: Well, given that these were my personal experience, yes. There were times that I paced in my study, sobbing. I don’t recommend this process. To write memoir so that it seems real, I had to mentally re-experience events and allow real emotion to drive the narrative and naturally highlight the details that evoke memory and feeling.

But I think you may be asking if I was concerned about the response of the Hasidic community, about bridging taboo. I hear that some in the Lubavitch community are already buzzing, and gossiping, about my memoir. Word is out that Uncovered is complete fiction. There will be repercussions. I will have to deal with them.

YZM: Even after you began to question the life you were leading, you describe in the book that sometimes you still went to the mikvah. What did this mean to you?

LL: I was living for years under layers of disguise, under a wig and long clothes, under the rule of Law that overruled our hearts, under the pretense of piety, heterosexuality, marriage and devotion to my husband. Then I’d go to the mikvah and strip naked to immerse. It took years, but over time, that became my truest, most honest prayer, a body prayer, as if I got to also strip myself of all pretense for a brief time, giving God my most secret self.

YZM: How did you come to start writing?

LL: It was because of all the secrets. Not only those in my own life, there were secrets throughout the community. Eventually, I was bursting with them. I decided, if I couldn’t talk, I’d write, through my long sleepless nights. I wrote fiction, another veil to hide behind, and opened all those secrets into my stories. Then I’d print out, delete, and hide the pages under my bed.

YZM: You had some strong writing mentors, among them Rosellen Brown, who has written groundbreaking fiction like Tender Mercies, Civil Wars and The Autobiography of My Mother and Gloria Steinem. How did they nurture you?

LL: Rosellen was my breath of air, a place where those secrets on the page generated no electric charge, no threat. And she was willing to read them! In the interest of craft, she directed me to read women writers of prose and poetry and taste real honesty on the page. She gently challenged my notions, not of religion, but of voice, of self-expression. And that changed me.

I met Gloria Steinem much later, after I’d been living an honest life for years. I’d tried and failed to write my memoir. Then, in 2010, I went to a tiny writing retreat for women to stay for a month. There were seven of us, and I sat down to dinner next to Gloria. I looked at her and realized I’d been trying to write a feminist memoir when I didn’t have the language. I had missed that era. I had a month of late-night conversations with her, walks in the woods, devouring books she recommended. That experience reframed everything. I began the memoir again. It’s different, and I think better, because of her. I think she would agree that we have remained friends.

YZM: How did your children deal with the profound changes in your life?

LL: Some better than others. We talk. I am an insistent presence in their lives, and Bubbie now to nine grandchildren.

YZM: What about your ex-husband?

LL: He never vilified me, even when the community did so, never spoke badly about me to the children, and always made it clear that I was welcome in what is now his home. We forgave one another. I think we did well.

YZM: What do you feel your former life gave to you?

LL: A mature and knowledgeable sense of my Jewish heritage, a habit of tzedakah, a deep conviction about avoiding cruelty to animals, a strong sense of community. I’m left an educated Jew, too much so, really, given the reams of liturgy, text, law, and commentary I carry around in my head with nowhere to put it. But there it is. In the end, I was changed, formed there, which is why I couldn’t go back to using my given English name. I remain Leah.

YZM: What did it take from you?

LL: It took from me exactly what societies too often take from a woman, only more so: voice above all, conviction that I can and must make my own decisions, that my life, as it seeps away, is more precious than anything, even anyone, else, the moral obligation to fill that life to overflowing and use it for good from that standpoint, not from a standpoint of selflessness. It stole my uniqueness, for years. I could go on, but I state the obvious.

But I am no victim. Ultimately, I made the choice to live that life, me, just as I made the choice to leave it. What did Hasidic life take from me? Exactly what I gave away voluntarily, however innocent and stupid I was, however little I valued what I tossed, completely not thinking how difficult it would be to reclaim. Sounds to me like a lot of young people. Sounds to me like a lot of women’s whole lives. Too many.