The Lilith Blog

August 9, 2016 by Elizabeth Mandel

When They Mess Up Your Daughter’s Ice Cream Order

A friend of mine—let’s call her Naomi––was in the local ice-cream store with her six-year-old daughter—Claire, for the purpose of this narrative. Claire, in her polite six-year-old voice, asked the woman behind the counter for chocolate-chip-cookie-dough topping on her cone.

A friend of mine—let’s call her Naomi––was in the local ice-cream store with her six-year-old daughter—Claire, for the purpose of this narrative. Claire, in her polite six-year-old voice, asked the woman behind the counter for chocolate-chip-cookie-dough topping on her cone.

Here’s what happened next.

The server, hearing “chocolate chip,” proceeded to dole out a generous spoonful of chocolate chips on top of the scoop. Naomi turned to Claire. “You wanted chocolate chip cookie dough, honey, not chocolate chips, right?” Claire: “Yes, but it’s OK. Chocolate chips on top are fine.” The server overheard, smiled, apologized for the error, and said she was happy to remake Claire’s cone. The little girl again said it was OK, it didn’t matter, she was fine with chocolate chips. She insisted on eating the cone as it was.

This isn’t a story about ice cream, of course.

- No Comments

August 8, 2016 by Rachel Hall

I Don’t Want My Daughter to Have My Holocaust Nightmares

Flickr.com, Philip Jones.

My mother claims she didn’t know about my reoccurring nightmares. I can’t imagine that I didn’t tell her, as I told her everything then. Has she forgotten? Or did I keep these dreams to myself because she’d already lived through that particular fear? I don’t know if I was aware of protecting her, or the need to do so. It’s possible that the dreams dissipated into my Midwestern morning routine—unloading the dishwasher, breakfast at our round kitchen table, the hilly trek to school where I was always the only Jewish child in my class. That is, until the next time.

In the dreams, I’m being chased, though at first it’s not clear by whom. As I run, I’m scanning for a hiding place, somewhere I won’t be detected by the men and their barking dogs. Sometimes this dream takes place in the outdoors, in woods not unlike those in my backyard—with its old hickory trees and oaks, low brush and vines that bottom out at a thin, patchy tributary to Hinkson Creek. In my waking life, I like to walk along the creek, watching water bugs skim the surface and thinking up story ideas. But in the dreams, the trees I love are too thin to hide behind, the lowest branches too high for me to reach.

- 1 Comment

August 5, 2016 by Marlena Maduro Baraf

Yellow Rose of Texas: 100 Birthday Candles in Panama

Panama City from the rooftops of the old quarter.

The D.J. at the end of the room has been instructed to open with “The Yellow Rose of Texas” and to play tía Adelaide’s old favorites. I look up. You can’t avoid looking up. The ceiling is as tall as a palm tree. We are in Casco Antiguo, the old, colonial quarter of Panama City where buildings date back as early as the 1600’s. My American husband and I took an Uber so as not to drive the narrow brick roads in the dark. The venue for the party is a bank built in 1904 that had been involved in the financing of the Panama Canal. Family have helped Adelaide with the preparations. Her sister-in-law, Connie, 92, brought Adelaide weeks before to taste the food and to approve the flowers.

When she called me in New York several months ago, tía Adelaide had said, “I invited all the people I care about. Will you come?” She’d insisted on a party on her 99th the year before, “in case I don’t make it to three digits.” I’d flown in for that too. It’s not every day that a family member becomes a centenarian.

Since Adelaide arrived in Panama in 1935, the Jewish community has changed dramatically. Our group—Kol Shearith Israel—is the smallest, descendants of Spanish-Portuguese Jews who arrived in Panama in the 1850s. There are now three Jewish congregations and six synagogues with a total of 15,000 members, the majority families of Sephardic Jews who emigrated from Arab countries—and from Israel after World War II. In recent years there have been waves of immigrants from Latin American nations in periods of trouble: Colombia, Argentina, and now Venezuela.

- 2 Comments

August 3, 2016 by admin

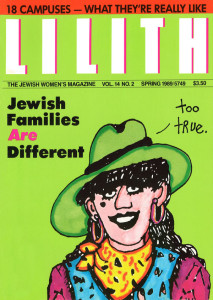

We’ve Got Issues—And We Want to Share Them

Lilith magazine, turning 40 this fall, is moving to a lovely new office in two weeks. Please help us find an appropriate home for some of our cherished back issues. (Alas, we can’t take them all with us.)

Do you teach a class that would enjoy having a print copy of a classic back issue? Are you part of a Lilith salon, writers group or rosh hodesh group that would appreciate these vintage issues?

We’ll gladly send boxed magazines of whatever issue you choose (or tell us to choose) in minimum quantities of 30 each. Please help us by sharing this offer widely.

You can choose from these (click on the links to see the full table of contents of each issue):

Winter 1976-77: Why did Golda Meir leave us a legacy of Zionism without feminism? The politics behind the Conservative movement’s endless debate over ordaining women rabbis. Cynthia Ozick argues brilliantly for women’s rights in Judaism. A vindication! Time to explore how I.B. Singer’s adored work is soaked through with misogyny.

Spring 1989: Family systems: Pioneer therapist Olga Silverstein on life, love and Jewish identity; Harriet Lerner on sisters pressed to achieve. The hit drama “Shayna Maidel” and its fractured families. Campus life for Jewish women: our insider’s guide. Gender, politics and power in Jerusalem through the eyes of E.M. Broner, Bella Abzug and more.

Spring 1989: Family systems: Pioneer therapist Olga Silverstein on life, love and Jewish identity; Harriet Lerner on sisters pressed to achieve. The hit drama “Shayna Maidel” and its fractured families. Campus life for Jewish women: our insider’s guide. Gender, politics and power in Jerusalem through the eyes of E.M. Broner, Bella Abzug and more.

Winter 2002-03: Jewish daughters and their African-American nannies tell stories of love and intimacy. Being the Catholic mother in a Jewish family. Praying for protection: sexual abuse by a Jewish father. The matronymic metamorphosis: what to name your child, and the importance of a mother’s surname.

- 1 Comment

July 26, 2016 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Wendy Brandmark on How Cities Have Become Characters in Her Fiction

Wendy Brandmark lives in London, but still thinks of herself a New Yorker.

Her first collection of short stories, He Runs the Moon: Tales from the Cities, charts the stories of thieves and outsiders, lost children and refugees. “My Red Mustang,” included in this collection, appeared first in Lilith’s fall 2012 issue. Brandmark talks to Lilith fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about her winding journey, both on and off the page.

YZM: You’ve lived in New York, in Boston, where you were an undergraduate, in Denver, where you did an MA in creative writing, and now London. Have these different cities informed your fiction?

WB: I have always lived in cities and in the case of both New York and Denver, the city itself has an identity, a character in my fiction. I grew up in New York, in the Bronx, and I think my memories of childhood, while not necessarily unhappy, have a kind of darkness and anxiety that colors my New York fiction. It is also the city I associate most with my Jewish origins and the immigrant experience in America, both of which feature in my writing.

I lived for two years in Denver in the 1970s and never returned. For me it was an alien uncomfortable city, an odd mixture of bland and raunchy, violent and gothic. This discomfort inspired stories about outcasts and thieves, dislocation and alienation. It seems remarkable to me that some 40 years later I’m still writing Denver stories. I think there is something about my experience of the city that gives me the freedom to explore characters on the edge. I’m waiting for there to be an end to the Denver stories, but this hasn’t happened yet.

- No Comments

July 22, 2016 by Sara Nuss-Galles

Sunday in Humboldt Park

It was a mid-September Sunday in 1950s pre-air conditioning Chicago. Most days, my siblings and I zigzagged between school, our third-floor apartment, and our parents’ convenience store a block south on Western Avenue. Seven days a week my parents toiled in the “Milk Depot,” selling glass gallons of milk so rich there was a layer of cream on top. In addition to the walk-in cooler’s array of dairy products, the shelves sagged with canned goods, loose cookies at 29 cents a pound, fresh bread and rolls, and $2.19 cartons of cigarettes. The loss leader milk and cigarettes often drew customers for a regular priced item or two, but the trade mostly came after the nearby A&P Supermarket closed.

I attended Casimir Pulaski School, several blocks away, and walked there in rain, shine, snow, and ice, annually garnering perfect attendance awards. In warm weather, the classrooms and halls teemed with the eau de toilette of kids—kids, like me, who ran and played every minute of recess and lunch hour. Back in class, sweated up and raring for freedom, I daydreamed about being transported to the park.

- No Comments

July 18, 2016 by Helene Cohen Bludman

Marching With My Rabbi for #BlackLivesMatter

My daughter Laurie and I arrived at the designated meeting point and found a crowd of at least several hundred strong. About 30 members of my synagogue—Beth David in Gladwyne, PA—were there too. The mood was calm and friendly.

My daughter Laurie and I arrived at the designated meeting point and found a crowd of at least several hundred strong. About 30 members of my synagogue—Beth David in Gladwyne, PA—were there too. The mood was calm and friendly.

The march began and we fell into the sea of humanity walking as one: young and old, skin color of all hues, men in kippot walking alongside men in clerical collars, children on scooters, several people in wheelchairs. White people and black people holding signs with the same message.

“This is awesome,” I breathed to my daughter as we stepped along.

“It sure is,” said a voice next to me. The voice belonged to an African American woman walking with a friend.

I reached out my hand and she clasped it.

“My name is Helene, and this is my daughter Laurie,” I said.

- 6 Comments

July 7, 2016 by admin

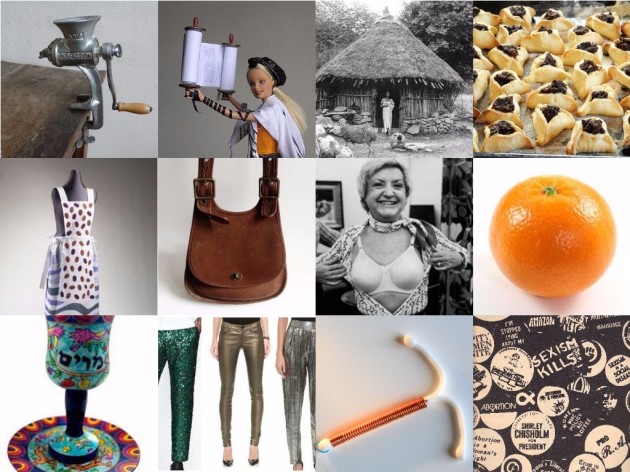

Tell Us! What Is a Jewish Feminist Object?

Maybe it’s lurking in your basement—or your subconscious. A baby carrier with tzitzit? Your IUD? Your Tia Malka’s cooking spoon? Tefillin Barbie? The pants you wore to your bat mitzvah?

Maybe it’s lurking in your basement—or your subconscious. A baby carrier with tzitzit? Your IUD? Your Tia Malka’s cooking spoon? Tefillin Barbie? The pants you wore to your bat mitzvah?

From the totally transgressive to the completely obvious, we want them all, in the full range of our identities—ethnic, racial, cultural, sexual, geographic, religious, tragical, comical.

Don’t hold back! Baby Jewish feminists need your wisdom. Send nominations to 40objects@Lilith.org with your name and the why behind the object(s). We’re standing by to select 40 for Lilith’s fall issue—kicking off the magazine’s 40th anniversary year.

For some samples of Lilith writing on objects and material culture (stuff we’ve loved in the past), see these articles:

- 1 Comment

July 6, 2016 by Eleanor J. Bader

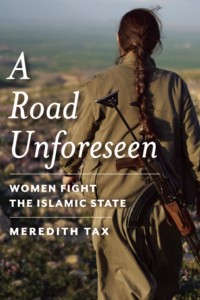

Writer-Activist Meredith Tax Gives Voice to the Women Fighting ISIS

Meredith Tax

Lord of the Rings author J.R.R. Tolkien wrote that “courage is found in unlikely places.” This truism, of course, has been repeatedly proven, as places steeped in poverty, neglect, hunger, and even war have produced unexpected exemplars of valor and fortitude.

Writer-activist Meredith Tax’s latest book, A Road Unforeseen: Women Fight the Islamic State—due out in late August from Bellevue Literary Press—zeroes in on a contemporary example of unanticipated moxie: The successful, if little-known, resistance to Muslim fundamentalism that has developed along the Syrian-Turkish border. In a newly-liberated region called Rojava, the towns of Afrin, Cizire and Kobane are currently under the control of a secular, multiethnic confederation of Arabs, Armenians, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Chechans, Kurds and Turkmen.

Writer-activist Meredith Tax’s latest book, A Road Unforeseen: Women Fight the Islamic State—due out in late August from Bellevue Literary Press—zeroes in on a contemporary example of unanticipated moxie: The successful, if little-known, resistance to Muslim fundamentalism that has developed along the Syrian-Turkish border. In a newly-liberated region called Rojava, the towns of Afrin, Cizire and Kobane are currently under the control of a secular, multiethnic confederation of Arabs, Armenians, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Chechans, Kurds and Turkmen.

Women, Tax reports, make up 40 percent of all organizations in Rojava, including those involved in local administration and decision-making. What’s more, every committee and oversight agency is led by one man and one woman, a conscious effort to promote female leadership and confront patriarchal cultural norms head-on.

Tax sat down with Lilith in late June to discuss activism, social change and women’s empowerment.

EJB: When did you become a feminist?

MT: I grew up in Milwaukee and my family was really sexist. As a kid in grade school I was told that a girl should not be too smart; my parents made it clear that no one would want to marry me if I did not tone it down. I was confused and didn’t understand why a boy wouldn’t want to be with someone who could help him with his homework! In sixth grade I started a petition to demand that girls be allowed to run for class president. As I got older I became more and more disgusted by the limited social possibilities for a girl like me. Reading saved me. Even before I left for college I’d read novels by Louisa May Alcott and plays by George Bernard Shaw that introduced me to feminism. I’d also read about the suffrage movement. Later, I went to Brandeis but even there, among a lot of smart women, our options were limited. After we graduated we could be teachers, social workers, or get a low-level job in publishing. I didn’t want that. I wanted to be a writer.

EJB: And you did! How did you make that happen?

- 1 Comment

June 29, 2016 by Rebecca Halff

Policing Girls’ Bodies Part Two: Legs

I wouldn’t mind reclaiming my high school nickname: Legs. It’s kind of cute. “Hey Legs!” my favorite school administrator would shout when she saw me roaming the halls, having absconded from class. I would look down at my knees feeling all the traits implied by that sassy little nickname: daring, provocative, cute, outrageous. I would grin at her and pull down my skirt a couple inches, as if to say, “Thanks for the heads up.” At Ramaz, the modern Orthodox day school I attended, my knees were absolutely unwelcome. She was saving me from a potential “tzniut (modesty) violation” by a serious dress code enforcer down the hall.

I wouldn’t mind reclaiming my high school nickname: Legs. It’s kind of cute. “Hey Legs!” my favorite school administrator would shout when she saw me roaming the halls, having absconded from class. I would look down at my knees feeling all the traits implied by that sassy little nickname: daring, provocative, cute, outrageous. I would grin at her and pull down my skirt a couple inches, as if to say, “Thanks for the heads up.” At Ramaz, the modern Orthodox day school I attended, my knees were absolutely unwelcome. She was saving me from a potential “tzniut (modesty) violation” by a serious dress code enforcer down the hall.

After davening every morning, one rabbi or another would deliver our morning announcements, which on a typical day went something like this: “There’s cereal in the lunchroom for those who want breakfast. There’s a winter clothing drive going on, so bring coats and scarves to the office. And…girls! Because of recent complaints about dress code, we feel the need to restate the requirements for sleeve and skirt length. The test for shirts is as follows: when you raise your arms above your head, your shirt should not rise to expose your midriff. As for skirts—how many times do we need to say this?!—your skirts should not be above-the-knee, nor should they be to-the-knee. They should cover your knees! If your skirt does not cover your knees, you will be sent to the office.” More than once (hence the nickname), I had been sent to the office, where a huge, shapeless, black garbage bag of a skirt awaited girls convicted of dress code violations.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...