by Sara Nuss-Galles

Sunday in Humboldt Park

It was a mid-September Sunday in 1950s pre-air conditioning Chicago. Most days, my siblings and I zigzagged between school, our third-floor apartment, and our parents’ convenience store a block south on Western Avenue. Seven days a week my parents toiled in the “Milk Depot,” selling glass gallons of milk so rich there was a layer of cream on top. In addition to the walk-in cooler’s array of dairy products, the shelves sagged with canned goods, loose cookies at 29 cents a pound, fresh bread and rolls, and $2.19 cartons of cigarettes. The loss leader milk and cigarettes often drew customers for a regular priced item or two, but the trade mostly came after the nearby A&P Supermarket closed.

I attended Casimir Pulaski School, several blocks away, and walked there in rain, shine, snow, and ice, annually garnering perfect attendance awards. In warm weather, the classrooms and halls teemed with the eau de toilette of kids—kids, like me, who ran and played every minute of recess and lunch hour. Back in class, sweated up and raring for freedom, I daydreamed about being transported to the park.

On Sundays, our parents often closed the Milk Depot for a while. Store hours weren’t posted on the door so when business was slow, they walked home for an overdue rest. They re-opened for the evening when local Polish housewives ran in for a missing item for dinner, or kaiser rolls and cold cuts for Monday’s lunch pails. It was a meager business, but between their fluent Polish and halting, recent-arrival English, my parents eked out a living.

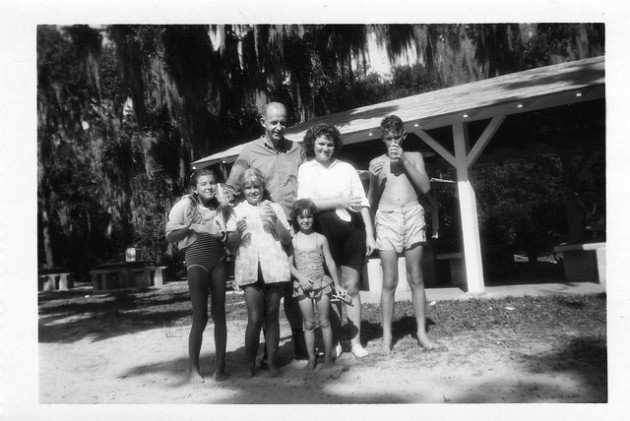

That Sunday was not unusually hot, but I was determined to go to Humboldt Park, where Jewish-Polish immigrant families gathered. Unlike my parents, their friends were usually free to escape their cramped apartments for fresh air and camaraderie on Sundays. After a week of grueling hours at menial jobs, some people played cards, but most just talked, relieved to speak their Yiddish mother tongue. Meanwhile, we kids darted through the park like uncaged birds.

My parents had scarcely come home that afternoon when I begged to escape the “hot” streets, the store and our apartment, for the tree-filled park. Tomorrow was school, and today I was desperate to see my friends Isaac and Frieda and play jump rope and chase. I yearned to sprawl on the grass and eat cold meat loaf or boiled chicken on the seeded rye bread that accompanied our every meal. But my parents were tired and wanted only to be off their feet for a while.

“Ess ist nisht azoi heiss,” my mother said, insisting that it wasn’t hot. I would not give up so easily. I snuck the thermometer off the hallway hook and leaned as far out of our third floor window as possible without falling out. Pointing the thermometer toward the sun I watched the red line rise … 81, 82, 83, 84, 85 degrees and climbing. I cupped my hands around the thermometer to retain the heat and presented it to my mother as she slumped at our turquoise Formica kitchen table.

“Look,” I said, in my mix of Yinglish. “Ess is azoi heiss ich schvitz.” It’s so hot I’m sweating. The tap water I’d dabbed at my hairline supported my plea.

“Oy,” my mother groaned, turning to my father. “Die vilst gein tsin park a bissel?” Do you want to go the park a little?

After a knowing glance at me, my father answered, “Yau.”

Victory!

In retrospect, my connivances were legendary, and seldom fooled my parents. But I felt proud that I steered them toward much needed friendship. In no time, shopping bags were stuffed with food, the thermos jug was filled with water, and off we went toting a worn chenille spread.

It was a grand afternoon for all. We kids shared food and hop-scotched the blankets in search of mischief. I don’t know what prompted him, but that day Isaac boldly followed us girls into the multi-stalled women’s bathroom. On spotting him, we got silly, screaming, giggling and coursing in and out of the stalls. Suddenly, a new adventure erupted. We pulled out yards and yards of toilet paper and ran wild around the park, trailing our fluttering tails behind us. Fortunately, the adults were too busy chatting to notice our high jinks.

The afternoon stretched beautifully before us with happy parents and rambunctious kids. But, around 4 or 5 pm, as if on signal, my parents nodded to each other and began packing up for our return to the store. On reaching the 2000 block of Western, my mother spotted a babushka-clad housewife tugging on the Milk Depot door, despite that the store was unlit and locked. My father pulled the car to the curb and my mother jumped out.

“Dzień dobry,” my mother called, waving the bundle of keys in her hand.

“Dzień dobry,” the woman answered, clearly relieved. “Farmers’ cheese and sour cream, I need, for pierogi.”

My mother opened the store and my parents resumed their daily toil. I stayed outside in the dwindling afternoon sun. Sated in spirit, I leaned against the still hot brick façade, reliving the day’s exploits as Sunday evening rolled slowly in.

Sara Nuss-Galles has been a commentator on Public Radio’s MarketPlace, and published in the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times, Lilith, and various anthologies. She has completed a collection of illustrated short stories, “Those Seven Deadly Sins.”