The Lilith Blog

October 11, 2016 by Elana Sztokman

Does Judaism Generate Eating Disorders?

Many women struggling with traumas around food and body shaming have stopped fasting on Yom Kippur. Cognitive behavioral psychologist Aliza Levitt, a specialist in eating disorders, says that for many women food is like a drug. “Like with any other drug, you can’t just take food away. It is a matter of life and death. Eating disorders have a high mortality rate, and you have to take that into account.”

But it’s more than that. The trauma of food triggered by Yom Kippur reflects a deeper problem in Jewish culture when it comes to food. The overemphasis on food in excess in Jewish life—so often served by women—combined with family surroundings in which body commentary is the norm, can launch different painful relationships with food and body.

- No Comments

October 11, 2016 by Elana Sztokman

Choosing Not to Fast: Eating Disorders and Yom Kippur

Last year on the eve of Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, Naomi Malka was busy. The High Holiday Coordinator and Mikveh Director at the Adas Israel Congregation in Washington, DC, she was preparing for a 6PM service for five thousand people and had no time to eat. For most people who observe this holiday – which, according to the Guttman Center, is the majority of Jews – the 25 hour fast is hard enough. But to start the fast already on an empty stomach and to be running around organizing and working, that is bordering on painful. But for Naomi, the challenge was even more extreme: she is also a recovering bulimic.

- 1 Comment

October 10, 2016 by Michelle Brafman

A Prayer for the Nameless

Marion Roth.

Each Yom Kippur our rabbi invites a few congregants to write a prayer leading up to the Yizkor Memorial service. Their words are always resonant and humbling. Two years ago, my short story “Sylvia’s Spoon,” winner of the 2007 Lilith Magazine Fiction prize, had been republished, and I mentioned to my rabbi that I was once again overwhelmed by the response to this tale of early pregnancy loss.

I told my rabbi that as a writer, if I get extremely lucky, a story that I send out into the world will come back to me in the form of more stories, a call and response of sorts. I described some of the moving and raw notes that I received about about miscarriages and abortions and babies never acknowledged or mourned.

It was only after my rabbi asked me to write a Yizkor prayer for these babies that I began to think of my own story. Almost twenty years ago, I’d lost a pregnancy a few months before Yom Kippur, and I remember sitting in shul, wondering if I had the right to recite Yizkor for my baby. I felt that there were no prayers for this life or for my husband or me. No way to heal.

On the eve of this Yom Kippur, I offer this prayer for anyone who has ever lost a pregnancy.

“A Prayer for the Nameless.”

On behalf of those who have endured the private grief of early pregnancy loss, I pray.

I pray extra hard for the men and women who are still trying to conceive. I wish for them a respite from the loneliest of lonely griefs. I hope they find comfort and promise somewhere, in prayer or the stories of the Biblical Sarah, Rivka, and Hannah or others who have shared this specific pain.

I pray for these men and women to have patience with well-meaning loved ones who fumble for the right words of comfort. There are no right words. I hope that they find the ear of a friend or a stranger and unburden themselves. Please God, allow them to let go of their shame and their timelines. Bless them with the courage to trust.

I pray the loudest for the nameless. The babies who never made it to the bimah, never received the rabbi’s hands upon their crowns or the blessings—Y’vorech’cho adonoy v’yishm’recho. Y’ayr adonoy ponov aylecho vichuneko—neither for a baby naming nor a bar or bat mitzvah.

I pray for the parents who named their babies and allowed themselves to wonder whether their children would inherit their grandmother’s perfect pitch or father’s love of board games. I pray for the parents who went on to make families, but who honor a due date and ponder a life that wasn’t, a broken memory that inhabits a crevice of their souls.

I call out to God, to give strength to those suffering from this hidden grief. Let us respond by remembering. Let us pray for them. And let us pray—for the nameless.

Michelle Brafman is the author of Washing the Dead and Bertrand Court, two works of fiction. Her writing has appeared in Slate, the Los Angeles Review of Books, LitHub, The Nervous Breakdown, Tablet, Lilith, and elsewhere. She teaches at the Johns Hopkins MA in Writing Program and lives in Glen Echo, Maryland with her husband and two children. www.michellebrafman.com

- 2 Comments

October 7, 2016 by Eleanor J. Bader

Homeless and Hungry: How One Nashville Doctor Reaches Out

The National Low Income Housing Coalition estimates that a Tennessee resident earning minimum wage—$7.25 an hour—would have to work 67 hours a week in order to afford a modest one-bedroom apartment in The Volunteer State.

It’s even worse in the capital city of Nashville. There, the NLIHC notes, today’s average market rents require earnings of $12.14 an hour for a one-bedroom flat, or $17.99 an hour for a two-bedroom.

- No Comments

October 7, 2016 by Hanna R. Neier

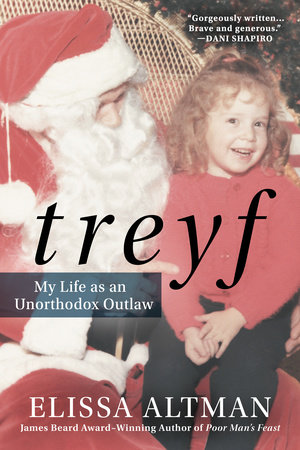

How Does Treyf Taste? An Interview with Elissa Altman

“Treyf… imperfect, intolerable… forbidden… A person can eat treyf; a person can be treyf.” The second memoir by award-winning author Elissa Altman (of Poor Man’s Feast fame), Treyf: My Life as an Unorthodox Outlaw (NAL/Penguin,) is a story of the struggle to find happiness, meaning and a sense of belonging in a world where traditions can both define and isolate us. In her latest work, Altman recalls in vivid detail her tumultuous coming of age and the ways in which food can express the most profound love while also being the catalyst for furious rebellion. From fried Spam [the “luncheon meat”] to her grandmother’s goulash, food marks the key moments of the author’s life in frank yet eloquent narrative.

“Treyf… imperfect, intolerable… forbidden… A person can eat treyf; a person can be treyf.” The second memoir by award-winning author Elissa Altman (of Poor Man’s Feast fame), Treyf: My Life as an Unorthodox Outlaw (NAL/Penguin,) is a story of the struggle to find happiness, meaning and a sense of belonging in a world where traditions can both define and isolate us. In her latest work, Altman recalls in vivid detail her tumultuous coming of age and the ways in which food can express the most profound love while also being the catalyst for furious rebellion. From fried Spam [the “luncheon meat”] to her grandmother’s goulash, food marks the key moments of the author’s life in frank yet eloquent narrative.

Here, Altman discusses with Hanna R. Neier the dual power of food and the need to connect to one’s past while still belonging to the present.

- No Comments

September 29, 2016 by admin

Where a Feminist Can Welcome the New Year

Shana tova! As 5777 approaches, Lilith has assembled for you a batch of feminist opportunities to spend the Days of Awe from the Bay Area to the mountains of Georgia. No matter what your High Holiday plans, look over this fascinatingly diverse list. From text studies, to chanting, to services free of charge and open to walk-ins, we hope you’ll feel inspired and renewed by seeing how you—or others—might celebrate the new year. Rosh Hashanah begins Sunday evening, October 2; Yom Kippur starts Tuesday evening, October 11.

Shana tova! As 5777 approaches, Lilith has assembled for you a batch of feminist opportunities to spend the Days of Awe from the Bay Area to the mountains of Georgia. No matter what your High Holiday plans, look over this fascinatingly diverse list. From text studies, to chanting, to services free of charge and open to walk-ins, we hope you’ll feel inspired and renewed by seeing how you—or others—might celebrate the new year. Rosh Hashanah begins Sunday evening, October 2; Yom Kippur starts Tuesday evening, October 11.

(And if you know of an event you think should be added to the list, email us—fast!—to info@lilith.org)

- No Comments

September 28, 2016 by Bernadette Murphy

A Divorcing Catholic Discovers Tashlikh

Last fall, I spent Rosh Hashanah weekend with a group of women in a rented house in Ventura, California, a beach town perched between Los Angeles and Santa Barbara. The plan was to have a simple Rosh Hashanah dinner together on Sunday night and then half our group would commute back to L.A. to attend services in the city and the other half—including me—would take a high-speed catamaran to Santa Cruz Island for a day of hiking and open-water kayaking, a way of communing with God through nature and starting the Jewish New Year.

Last fall, I spent Rosh Hashanah weekend with a group of women in a rented house in Ventura, California, a beach town perched between Los Angeles and Santa Barbara. The plan was to have a simple Rosh Hashanah dinner together on Sunday night and then half our group would commute back to L.A. to attend services in the city and the other half—including me—would take a high-speed catamaran to Santa Cruz Island for a day of hiking and open-water kayaking, a way of communing with God through nature and starting the Jewish New Year.

This was one of the first outings I’d made since telling my husband of 25 years that I no longer wanted to be married.

- No Comments

September 28, 2016 by Lori Wald

Who by Chicken?

Your synagogue is packed. Parking spaces scarce. You’ve been careful to hold on to your ticket, which is required for entry. These are the days of awe. The time to contemplate the state of your mortality. In the sanctuary, a man blows a ram’s horn to signify the seep of the ancient into the present at a time when the congregation prays for the future. Please God. Inscribe me and my family into your Book of Life. As always, you ask for one more year. Around you, they recite the poem with the punch list of how one might perish. On Rosh Hashanah it is written and on Yom Kippur it is sealed: Who shall live and who shall die. Who by fire and who by water? Who by sword and who by beast? Who by hunger and who by thirst? Who by earthquake and who by drowning? Who by strangling and who by stoning?

Your synagogue is packed. Parking spaces scarce. You’ve been careful to hold on to your ticket, which is required for entry. These are the days of awe. The time to contemplate the state of your mortality. In the sanctuary, a man blows a ram’s horn to signify the seep of the ancient into the present at a time when the congregation prays for the future. Please God. Inscribe me and my family into your Book of Life. As always, you ask for one more year. Around you, they recite the poem with the punch list of how one might perish. On Rosh Hashanah it is written and on Yom Kippur it is sealed: Who shall live and who shall die. Who by fire and who by water? Who by sword and who by beast? Who by hunger and who by thirst? Who by earthquake and who by drowning? Who by strangling and who by stoning?

But never mind about that. This is the time when you and all Jewish mothers everywhere prepare for the arrival of the family and attempt to make this holiday as authentic and real and Jewish as possible. Obviously, it’s about the meal. Nothing is more sacred than food.

- No Comments

September 23, 2016 by Alix Wall

Rediscovering Jewish Roots in Poland through Coca-Cola

Gunnar Inge Gjøvik Sortland

The six degrees of separation is usually only two or three when it comes to Jews. Poland ended up being a perfect example when I attended a “Seminar on Wheels” for Jewish professionals with the Taube Center for the Renewal of Jewish Life in Poland.

We keep hearing that many Poles are discovering Jewish roots, but when I visited Poland recently I met precious few of these reported multitudes. “In August, everyone is on vacation,” we were told.

- No Comments

September 16, 2016 by Naomi Danis

History on Trial: The Docudrama

I hope there will be lots of conversation about “Denial,” the riveting new docudrama about eminent historian Deborah Lipstadt’s fight to defend her scholarship against a vicious Holocaust denier. The libel suit brought against the Emory professor–and her publisher–by David Irving, whom she described as a Holocaust denier in her 1993 book Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory. Irving brought the suit in England, where in such cases the defendant has to prove her innocence, the opposite of the American system, where in such cases the defendant has to be proven guilty.

I hope there will be lots of conversation about “Denial,” the riveting new docudrama about eminent historian Deborah Lipstadt’s fight to defend her scholarship against a vicious Holocaust denier. The libel suit brought against the Emory professor–and her publisher–by David Irving, whom she described as a Holocaust denier in her 1993 book Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory. Irving brought the suit in England, where in such cases the defendant has to prove her innocence, the opposite of the American system, where in such cases the defendant has to be proven guilty.

The film, in which Rachel Weisz stars, is based on Lipstadt’s 2005 book History on Trial: My Day in Court with a Holocaust Denier (2005). This screenplay, written by David Hare, may be indicative of a new 21st-century era of Holocaust film tackling a fundamental question we haven’t needed to ask in quite this way until now: How do we know what we know?

In the trial, for strategic reasons, and also to protect them from abusive bullying by the bigoted plaintiff, the defense kept upset Holocaust survivors from testifying. And, following the unilateral decision of her expert barrister and solicitor, supported by a large team of researchers, Lipstadt was kept off the stand too.

All clear thinkers agreed that it would be an absolute disaster if the case were lost. Some, including leaders of the British Jewish community, urged Lipstadt to settle the case out of court, but she insisted on fighting the charge directly.

One small and perhaps not so incidental detail about the film: it doesn’t throw in any extraneous romance to sell its story. We don’t learn anything about the relationship status of any of the characters, a tribute to the seriousness and sufficiency of the film’s subject.

Lipstadt (played wonderfully by Weisz)— is tough and relentless and often funny, like the historian herself—and the film powerfully connects the many themes of hatred spewed by Irving: his racism and sexism on top of his rampant anti-Semitism.

“Denial” is a film well worth seeing—and discussing.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...