The Lilith Blog

December 15, 2016 by Erika Dreifus

A Poem for Vayishlach (“Dinah Speaks”)

A Poem for Vayishlach (“Dinah Speaks”)

After my brothers killed my husband and his father

and all the men of my new city,

after they took me forth and claimed

everything—and everyone—that remained

for their own,

they returned home with their new treasures,

and with me.

Our father spoke to them in dismay;

to me, he said nothing.

And here I’ve passed all the years since.

No more gallivanting.

I stray from my father’s tents

only to companion those whom my brothers

captured and spoiled,

whose suffering surpasses mine by far.

To them alone, I speak.

I am sorry, I say.

I am so very, very sorry.

Erika Dreifus writes poetry and prose in New York. Visit her online at www.erikadreifus.com and follow her on Twitter @ErikaDreifus, where she comments on “matters bookish and/or Jewish.”

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.

- No Comments

December 14, 2016 by Susan Weidman Schneider

You’re the Chief Procurement Officer of Your Life

A large screen shows a small girl whose skin shimmers. She is standing outside of a “rat hole” mine for mica. “The sparkle in lipstick, in nail polish” comes in part from her labor, Justin Dillon, founder/CEO of Made in a Free World, announces to the Jewish women philanthropists.

A large screen shows a small girl whose skin shimmers. She is standing outside of a “rat hole” mine for mica. “The sparkle in lipstick, in nail polish” comes in part from her labor, Justin Dillon, founder/CEO of Made in a Free World, announces to the Jewish women philanthropists.

Another story mentions a five-year-old boy who works diving for fish. If he surfaces too quickly, to breathe, he is beaten on the head with a wooden oar.

Dillon is speaking about slavery and human trafficking to the Lions of Judah, Jewish women philanthropists from around the world who are gathered at their conference, “Hear Us Roar” in Washington, D.C., in 2016. Susan Stern, past chair of National Women’s Philanthropy of the Jewish Federations of North America, describes the participants to the speakers in this session as “the top women philanthropists in the world. They happen to be Jewish.”

“There are huge profits from slavery, so charity alone won’t make a dent,” said Dillon, who has been tasked by the government to “purify the government supply chain,” making sure that none of its suppliers use trafficked labor, “making sure that there isn’t slave labor going into farming the fish. You are the chief procurement officer in your life — with every transaction think about who makes what you’re buying.” Stern added that the atrocities of human trafficking and sex trafficking were very profitable because of the demand for consumer sex and ever cheaper consumer goods.

Lilith asked, “How can intervention occur? What do you say if you suspect that someone brought in by a third party to clean your house or rake your leaves might be a labor slave?” Susan Stern replied, “I ask in the nail salon: ‘Where do you go at night? Do you ever go to the movies?’ in order to give people an opening to say a little bit about their lives.” Stern also suggested hotline stickers in “every synagogue bathroom, every summer camp bathroom, because camping brings in foreign counselors and you want to make sure they’re protected.”

Amelia Dornbush also contributed to this article.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.

- No Comments

December 12, 2016 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Familial Contempt and Delicious Komish Broyt

My grandmother Tania had nothing but contempt for her mother-in-law, Toibe Breittleman. In Tania’s view, the woman was coarse, vulgar and had questionable morals. My grandfather’s mother did not have it easy. When her husband left Russia in search of the better life promised by the lady with the lamp, Toibe remained behind in their dirt-floored home with three small children to raise. There was a single overcoat that they took turns wearing, and she freely gave the children cigarettes to help stave off the hunger pangs; my grandfather began to smoke, with her blessing, at the age of eight. Her desperation—and resourcefulness—drove her to seek work in hotel where she met friends in higher places—gentlemen, army officers—whom she charmed and entertained in ways that were perhaps not entirely kosher. These men supplied food, money and cigarettes and it was her rumored association with them that followed her to America and made my grandmother decide she was a “loose woman.”

Tania, in shorts, standing with my mother who was about 11 in this photo.

Toibe’s husband died but she managed to get along on her own. She was a mover and shaker in her small community of Detroit Jews; she organized elaborate picnics and charged people to attend; the money she raised was donated to help other immigrants like herself. She dyed and curled her hair, wore make up every day and never went anywhere without high heeled pumps. Her dressing table was filled with glass bottles of scent and aromatic unguents, and a flounced, beribboned boudoir doll sat on her bed. After buying a new dress, she would immediately cut out the neckline to expose a more daring swath of decollatage, and then, as if that weren’t enticement enough, sewed sequins all over the bodice. When Tania, then in her twenties, purchased a rather daring pair of Bermuda shorts, Toibe ran right out and purchased an identical pair of her own.

Privately, my grandmother shuddered in horror. Her mother-in-law was a floozy, pure and simple. And yet she had to acknowledge that Toibe was a something of a magician in the kitchen, known for her cooking and baking—which she did in her trademark high heels. These were skills my grandmother prized and which she had not learned from her own mother, Miriam.

Where Toibe had been literally, dirt poor, Miriam’s life back in Russia had been quite different. Her husband, my maternal great-grandfather, was a tanner, an occupation that was considered revolting—the animal skins were softened with a mixture that contained large quantities of urine. There were many professions to which Russian Jews were denied access but tanning was not one of them, possibly because it was so disgusting few people wanted to do it. My great-grandfather became a successful and wealthy man, and my grandmother, the second youngest of twenty-two children (Miriam was possessed of a Biblical fertility) recalled a fine house with parquet floors, crystal chandeliers, and velvet drapes. There was a piano, on which her older sisters were given lessons, and a room for dancing, for they had those lessons too. Some of her brothers went to a military academy. Miriam did not cook for her enormous family; she had servants for that.

But this life of ease and affluence came to an abrupt and savage end when my great-grandfather left for a business trip from which not he, but his bloodied corpse returned, shrouded in a canvas mail sack. Shocked and grief-stricken, Miriam swallowed poison; my grandmother spoke of the “burns around her mouth.” But Miriam was more resilient than she knew—she did not die. Instead she rallied, intent on bringing the five children remaining at home to America. Then Revolution broke out, making Miriam even more desperate to escape. She left her two tiny daughters—my grandmother was six, her younger sister four—while she went out to sell the contents of her home in order to book passage for the trip; she stood mattresses in front of the windows, many of them now shattered, to keep rocks and stones from being hurled in during her absence. Silver, jewelry, crystal, porcelain—all sold, all gone. She kept only five silver soup spoons, and tucked them deep into the recesses of her bag, where they remained until she reached America.

Tania with my uncle.

The polar opposite of Toibe, Miriam was prim, reserved and modest. Her gray hair was always secured in a neat bun. She wore plain, cloth coats, lace up shoes and unadorned leather handbags in two colors only, navy or black, and white blouses that she periodically boiled on the stove in bleach-laced water. For special occasions, she donned a strand of tiny red coral beads and coral earrings.

Yet my grandmother wanted to learn to cook, and especially bake, and so she had to set aside her disdain and turn to her mother-in-law. And Toibe, who was well aware of her daughter-in-law’s contempt, grudgingly said yes, which was how Toibe came to teach my grandmother to make the crunchy, twice baked cookies that were called komish broyt—almost bread.

My meticulous grandmother was an apt pupil and may have even outdone her teacher. Her cookies, studded with walnuts and raisins, and dusted with cinnamon sugar, were thin, light, crisp and delicious. She made them for all the Jewish holidays, brought them to Shabbos dinners, bris celebrations and shivas. When my mother lived in Israel as a young woman, my grandmother wrapped the cookies individually in tissue paper and packed them in tins that she mailed overseas, where they would arrive safely, with scarcely a cracked one in the batch. She taught my mother to make them, though my mother, more bohemian artist than balbusta, would either cut them too thick, or make what to to my grandmother would have been unthinkable alterations—chocolate chips if she had no raisins, peanuts in lieu of walnuts. These cookies were a staple of my childhood and as a young married woman, I began to bake them too; they quickly became a favorite of my own family.

Miriam is long gone now. So are Toibe and my grandmother Tania. The two women who rarely saw eye to eye were somehow united in the kitchen. The recipe and the silver spoons are their conjoined legacy, all that remains of a vanished world. I’ve given the recipe to my daughter Kate—she is the fifth generation of women in our family to have it—and the spoons will be hers one day too. I hope she’ll bring them along into whatever new life she makes for herself; I’d like to think that the spirits of Toibe and Tania will be watching.

Toibe and Tania’s Komish Broyt

4 cups flour

2 teaspoons baking powder

1/2 teaspoon baking soda

4 eggs

1/2 cup orange juice

1 cup oil

1cup sugar

1 teaspoon vanilla

3/4 cup white raisins, plumped with boiling water for 10 minutes, then drained.

3/4 crushed walnuts

Cinnamon sugar to taste

Mix dry ingredients first; gradually fold in wet ingredients, raisins and nuts. When batter has been blended, refrigerate for 30 minutes. Then use batter to form a loaf in a pan, dust with cinnamon sugar and bake for 30 minutes @ 350 degrees. Let cool entirely and with a serrated knife cut in thin slices and bake again at 325 degrees, turning to brown evenly on both sides. Check often to make sure they do not burn.

- No Comments

December 11, 2016 by Danica Davidson

This Bestselling Author Talks Judaism, Activism and Her New Book

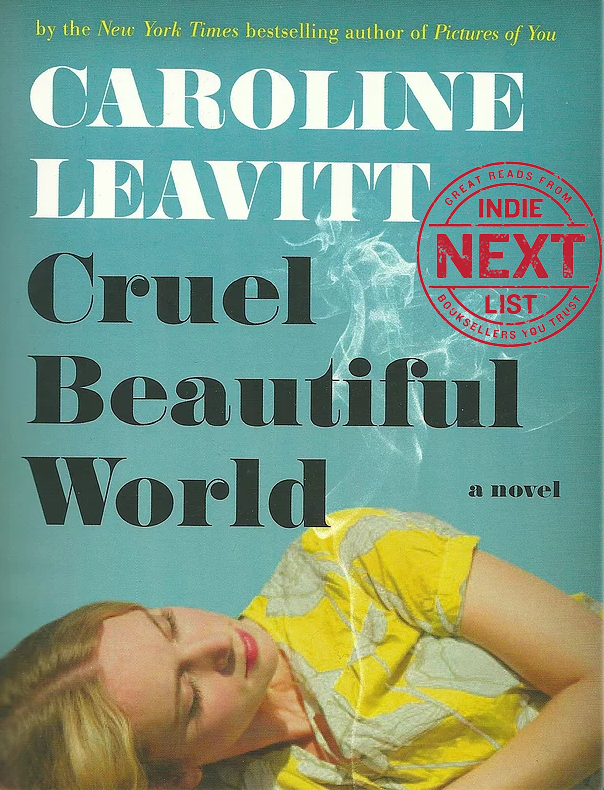

New York Times bestselling author Caroline Leavitt’s new book, Cruel Beautiful World, shows a family of Jewish women living through the cruelty and beauty of the world in 1969-1970. High schooler Lucy runs away with an older man, her sister Charlotte experiences the outside world in her time at Brandeis, and their guardian Iris discovers new love in her eighties. Against this intimate portrait of family, there is also a background of women’s rights, political upheaval and war.

New York Times bestselling author Caroline Leavitt’s new book, Cruel Beautiful World, shows a family of Jewish women living through the cruelty and beauty of the world in 1969-1970. High schooler Lucy runs away with an older man, her sister Charlotte experiences the outside world in her time at Brandeis, and their guardian Iris discovers new love in her eighties. Against this intimate portrait of family, there is also a background of women’s rights, political upheaval and war.

Leavitt has written about Jewish women’s lives in fiction before, and now with Cruel Beautiful World, she speaks to author Danica Davidson about autobiographical elements, Jewish literature and the lives of Jews and women now compared to 1970.

- No Comments

December 10, 2016 by Amelia Dornbush

Their Poultry Is Kosher. Shouldn’t Their Labor Practices Be?

“For us, Kashrus means aiming higher,” declares the website of the Birdsboro Kosher Farms. “We take no shortcuts and accept no excuses.”

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), however, begs to differ. On September 2, the government issued citations to Birdsboro Kosher Farms for two willful and eight serious safety and health violations. This followed an investigation that began in April after a worker’s thumb was amputated.

- No Comments

December 9, 2016 by Karen Skinazi

Following Our Cycling Foremother: Spinning Fiction on Two Wheels

Karen Skinazi and her bike. Soon, her surroundings will be transformed into an alternate world through the magic of pedaling.

After dropping my three kids off at school, I hop on my bike and head to work. The ride always seems short—too short to fully work out the stress that accompanies the morning routine. The little one wouldn’t get out of bed. The middle one wouldn’t get off his screen. The oldest one couldn’t find his standard-issue gym shorts, couldn’t wear any other shorts, and was not going to school. The walk from our house to their school is no less painful: the older two fight, the little one keeps stopping (“my.feet.can’t.move”), and I’m yelling the whole way, clutching the handlebars of my bike, which I’m more than ready to ride.

As soon as I’m on my bike, however, the tension begins to dissolve. My surroundings dissolve too, in cinematic fashion, houses disappearing, asphalt road becoming a dirt path, the trees suddenly lush and tropical.

- No Comments

December 8, 2016 by Matilda Feder

Dr. Ruth Has a Dollhouse, Too.

“A dollhouse is not just a toy, it represents wishes,” says Dr. Ruth. Photo by Chris Chrisman.

Dr. Ruth Westheimer is 88 years old, but you wouldn’t know it when she took the stage Monday night at the National Building Museum to talk about her incredible life, dollhouses, and of course, her career as a psycho-sex therapist, with NPR’s Special Correspondent Susan Stamberg.

The National Building Museum has the wonderful Small Stories exhibition on display— a selection of the Victoria and Albert’s very best dollhouses and the “Dream House” installation of imaginatively crafted rooms created by American designers and artists.

But why talk to Dr. Ruth about dollhouses?

Stamberg asked Dr. Ruth that question first, and she had the answer right away (not, of course, before cracking a sex joke. She had to start the evening with a sex joke.)

- No Comments

December 7, 2016 by Ellen Weininger

A Victory at Standing Rock, But It’s Not Over Yet

On Sunday afternoon, the Obama administration and the United States Army Corps of Engineers announced the denial of the easement to Dakota Access, LLC to drill under Lake Oahe and the Missouri River for the Dakota Access Pipeline. The Army Corps of Engineers say they will conduct an Environmental Impact Study (EIS) and explore other routing possibilities. This remarkable victory at Standing Rock by nonviolent indigenous activists over formidable energy companies is an historic moment.

Should we celebrate this important turn of events in the struggle against the Dakota Access Pipeline at the Standing Rock Sioux reservation in North Dakota and simply go home? Not so fast!

- 1 Comment

December 6, 2016 by Eleanor J. Bader

Holocaust Survivor Helena Weinrauch on Trauma and the Joy of Dancing

Helena Weinrauch. Photo courtesy of Karen Goldfarb.

When Helena Weinrauch was 88 years old, she found a promotional flyer from the Fred Astaire Dance Studio in her mailbox. The leaflet promised a free lesson followed by a party.

Four years later, Weinrauch has become a Dancing Angel, a title given to her by the Manhattan Ballroom Society, and currently spends five hours a week doing the Fox Trot, Merengue, Samba and Tango.

“When I dance I forget everything that bothers me,” she told Lilith reporter Eleanor J. Bader. “My fear disappears. There was never time in my life for dancing before this. There were always more important things to do, but before I say goodbye to this world I want to do something I always dreamed of doing. I think I’ve earned it.”

- 2 Comments

December 5, 2016 by Katherine Olstein

Two Women Team Up to Revitalize Music from a Polish Shtetl

Shortly after scientist and musician David Goldfarb moved to Highland Park, New Jersey, in 1989, he joined the Conservative synagogue, where he met Milton and Frieda Frant, an outgoing older couple. Playing Jewish geography on the phone, his parents on the West Coast asked if he had come across anyone named “Milton Frant” because, he should know, their families were related by marriage.

Years later, at the outset of clarinetist Goldfarb’s first class at KlezKamp 2008, instructor Adrianne Greenbaum handed out sheet music, saying that it was from the Frand Klezmorim and naming Milton Frant’s daughter, Sharon Frant Brooks, as her source for the historically significant arrangement. This meant that the music Goldfarb was about to play was from his family’s past.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...