by Danica Davidson

This Bestselling Author Talks Judaism, Activism and Her New Book

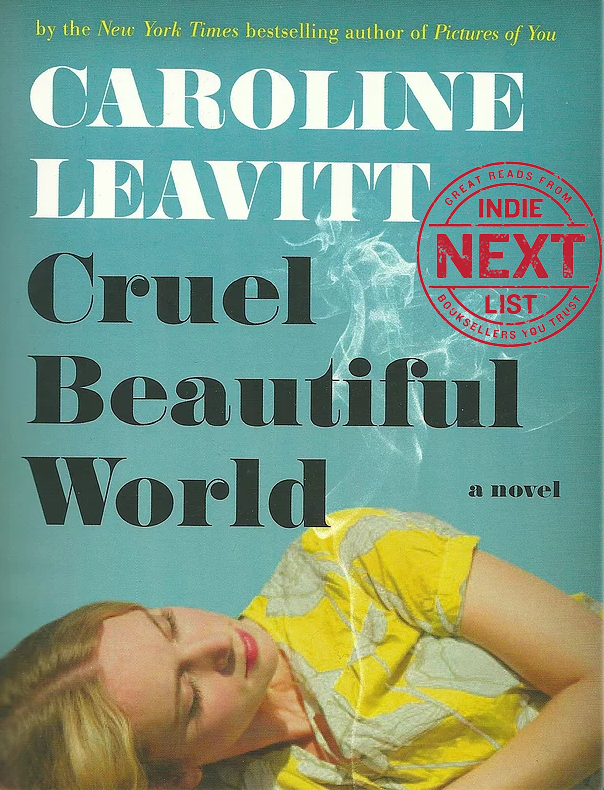

New York Times bestselling author Caroline Leavitt’s new book, Cruel Beautiful World, shows a family of Jewish women living through the cruelty and beauty of the world in 1969-1970. High schooler Lucy runs away with an older man, her sister Charlotte experiences the outside world in her time at Brandeis, and their guardian Iris discovers new love in her eighties. Against this intimate portrait of family, there is also a background of women’s rights, political upheaval and war.

New York Times bestselling author Caroline Leavitt’s new book, Cruel Beautiful World, shows a family of Jewish women living through the cruelty and beauty of the world in 1969-1970. High schooler Lucy runs away with an older man, her sister Charlotte experiences the outside world in her time at Brandeis, and their guardian Iris discovers new love in her eighties. Against this intimate portrait of family, there is also a background of women’s rights, political upheaval and war.

Leavitt has written about Jewish women’s lives in fiction before, and now with Cruel Beautiful World, she speaks to author Danica Davidson about autobiographical elements, Jewish literature and the lives of Jews and women now compared to 1970.

Danica Davidson: It seems as if there are some really autobiographical parts of Cruel Beautiful World. What is inspired by your life?

Caroline Leavitt: Several things. The first thing started when I was seventeen. I was the only Jewish girl in a Christian high school. It was a very working class city, and I was bullied a whole lot. I sat behind this girl in study hall who was really friendly to me and helpful. Because everybody liked her, when they saw she liked me, they left me alone. While I was telling her what my plans were — that I was going to go to Brandeis, that I was going to be a writer — she told me she was engaged already, and that she’d been engaged all year to a much older man. They were just waiting until she was eighteen to marry. She said the only thing wrong with him was that he was a little controlling.

So I thought that was weird. I was in my second year of college when I happened to see a news item in the newspaper that said her much older boyfriend had murdered her, had stabbed her forty-two times. I was appalled when I read that, because I couldn’t figure it out. For someone to do such a violent act, wouldn’t she have noticed he was violent before? Wouldn’t somebody else have noticed, and why didn’t they help her? I couldn’t get my mind around that and I couldn’t stop thinking about her until ten years later, when I got into a relationship myself with someone who was sort of controlling. I began to realize how insidious it can be and how quiet. The guy I was with never raised his voice. He never raised his fists; there was never any violence. But he would just keep repeating the same things about me that he wanted me to do over and over. If you listen to them for a while, you start to believe them. I actually couldn’t leave him until I found out that he had gone in my computer and changed a chapter in my novel and wrote jokes in it. I kept saying, “How could you do this? This is mine.” And he said very quietly, “Caroline, this is the way it’s going to be from now on. There’s no you, there’s no me. There’s only us.” In that moment, I understood my friend from high school, and I also got very nervous. And I left.

But there are other autobiographical parts, too, though those didn’t come until later. One is the character of Iris, who starts to bloom in her eighties. That’s my love story to my mom, who actually did the same. The siblings in the novel, Charlotte and Lucy, are very much my sister and me; and I wanted to get that into the novel.

DD: How does being a Jewish woman affect Cruel Beautiful World?

CL: The book is set in 1969 and 1970, and that’s the year where everything changed. Especially in the 70s, when the peace moment started to turn violent and about 80% of the radicals were Jewish. I was at Brandeis University then. My mom used to take me to peace marches in the 60s, and in the 70s all of a sudden it was different. There were two girls, Susan Saxe and Katherine Ann Power, who decided they had enough of peaceful demonstrations and they were going to get a gun and rob a bank in Boston and use the money for the revolution. They did end up robbing a bank, and they killed someone [Police Officer Walter Schroeder] who was a father of nine. They were on the FBI Most Wanted list and they went underground for years and years. I went to Brandeis a year after they did that, but everyone at the school was totally discombobulated and scared because everything seemed upside down. We didn’t know what we were supposed to do in the light of this. Brandeis was the center of the student strike movement, so that feeling of the-world-is-supposed-to-be-beautiful-but-it-actually-can-be-cruel is very much a part of my novel. Also, the whole idea of being Jewish and being an activist and trying to make a better world, and what does that mean? I wanted to explore that.

DD: How does being a Jewish woman affect your writing in general?

CL: I think it does in terms of my cultural upbringing. My family wasn’t really very religious, but we raised our son to know his heritage. It suddenly became very important to me. Knowing what your past is and what your ancestors have gone through and making it a better world, that’s all part of my novel.

DD: The characters in Cruel Beautiful World are clearly Jewish, but you don’t talk about it all the time. Why did you decide to approach their Jewishness in this way?

CL: Because for me it was very much like that in the 60s and 70s. People were experimenting. I went to a very Jewish college, but even at Brandeis people were experimenting with different Eastern religions. People were starting to say they were spiritual rather than religious. That was my experience at the time, and I wanted to capture it in my book. It was almost like we all knew that we were Jewish, and we all respected our heritage, but we were also all probing fingers looking for whatever else we could find that would give us spiritual solace.

DD: What are your thoughts on contemporary Jewish literature?

CL: Oh, I think it’s great. I’m a big admirer of Michael Chabon. I think especially now, in this political climate, the more Jews write and make ourselves known and understood, the better it is for everyone.

DD: The book also talks about women’s rights and their place in the world in America in 1969-1970. How do you think women’s rights in the time of the book compare to how things are now?

CL: Well, that’s a difficult question. I remember in the 70s, it was a big thing about women’s lib. The thing about it is, I had friends in SDS (Students for a Democratic Society), which was pretty revolutionary. They talked a lot about women’s rights, but it was still the women who had to do the dishes. They couldn’t do the more interesting work. Now, before the last five years, I think women were making incredible strides and they were being given more opportunities, more power, more everything. Now I worry that we’re stepping back. I’ve heard things that are going on in the political arena, things like anti-Semitic comments that are very scary, and comments about how women shouldn’t go into the sciences or math. So I think it’s a call to action for every women, Jewish or not, to make our voices heard and make sure we can still be out in the world.

DD: How can people find out more about you and your work?

CL: They can just go to my website, CarolineLeavitt.com, or they can follow me on Facebook.

I have one more thing I do want to talk about. It’s a message to everybody, especially women: never give up. Just keep going. This is my eleventh book. My first book was a success, then books two through eight were failures. I bumped around from publisher to publisher. My ninth novel, Pictures of You, was rejected on contract by the publisher, and I thought my career was over. But I didn’t give up, and that book was picked up by Algonquin and then it became a New York Times bestseller. So I always tell people you have to stand up for yourself and you have to really push for what you want, especially if you’re a woman, because a lot of times people think you’re being overly dramatic when you’re expressing what you want. I just want to leave with that message. Do not give up.

Danica Davidson is the author of the Overworld Adventure series, Manga Art for Beginners and Barbie: Puppy Party.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.