The Lilith Blog

April 21, 2017 by Rebecca Krevat

How Rape Survivors Are Using Art

April is Sexual Assault Awareness Month. As a survivor and survivor advocate, I struggle during this time with the way media portrays us. While individual stories of survival and victimhood are critical, far too often some of us feel boxed in by what we call the “sad rape girl” narrative. This is what happens when journalists reduce survivors down to their narratives of victimhood, of loss of control, of lack of agency, and refuse to let us share how we’re fighting back, of how we’re experts in law or advocacy around sexual violence.

This is part of why I was so interested in attending the recent public conversation “Consent/Dissent,” between by Emma Sulkowicz and Aliza Shvarts, two artists who challenged the status quo of survivor and victim narratives through performance art.

Emma Sulkowicz is best known for her “Mattress Performance” held at Columbia University. She carried her dorm mattress around with her each day her rapist still attended the University. During this time, Emma noticed that suddenly everyone was an expert about her rape—that everyone had all these ideas about what rape survivors would and would not do. Emma was provoked by these commentaries to do something that a “real” rape survivor would never, ever do – in “Ceci N’Est Pas Un Viol” (2015; “This Is Not a Rape”) she recreated her rape experience on camera as a performance piece.

- No Comments

April 20, 2017 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Maira Kalman’s Mother’s Closet Looks Nothing Like Yours

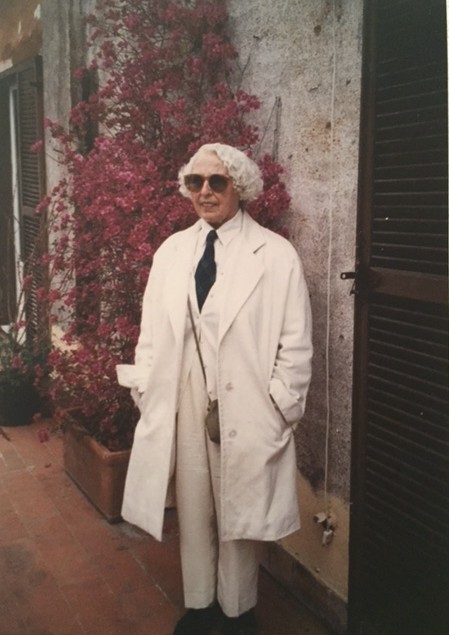

Long before Martha Stewart and Marie Kondo showed up on the scene, there was Sara Berman (1920-2004), an avatar of order who might have taught even those two domestic goddesses a thing or two. Berman, mother of artist Maira Kalman, is now the subject of an exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that will run from March 6 through September 5, 2017. Or rather, it’s Berman’s closet, recreated by Kalman and her son Alex, that is the subject; the artfully arranged and preternaturally tidy shelves and hanging rods offer us a privileged view of Berman, literally, from the inside out.

Long before Martha Stewart and Marie Kondo showed up on the scene, there was Sara Berman (1920-2004), an avatar of order who might have taught even those two domestic goddesses a thing or two. Berman, mother of artist Maira Kalman, is now the subject of an exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that will run from March 6 through September 5, 2017. Or rather, it’s Berman’s closet, recreated by Kalman and her son Alex, that is the subject; the artfully arranged and preternaturally tidy shelves and hanging rods offer us a privileged view of Berman, literally, from the inside out.

Nestled in between a spacious and low-slung room designed and decorated by Frank Lloyd Wright and the ornate dressing room of Arabella Worsham-Rockefeller, the closet represents Berman’s life from 1982 to 2004, when, as a divorced woman, she inhabited a studio apartment at 2 Horatio Street in Manhattan. Shoes, clothes, linens, beauty products, luggage, and other necessities are organized and arranged with unerring precision, exactitude and love. From this collection, humble and yet somehow sacred, we can read between the lines of the story outlined in the wall notes composed by Kalman and her son:

- 2 Comments

April 19, 2017 by Stephanie Baric

Adio Querida: TV Spotlights Sephardim in the Balkans

mhzchoice.com

A couple of years ago as my mother was browsing Serbian shows online, she stumbled across “The Scent of Rain in the Balkans,” a Serbian television series based on the bestselling novel of the same title by Gordana Kuic, centering on the tragic destiny of a poor Sephardic family from Sarajevo between 1914 and 1945. As the series opened with the song “Adio Querida,” a famous Ladino song titled “Goodbye My Beloved” in English, my Serbian Jewish mother forced me to watch the opening episode about, as she put it, “our beloved but forgotten Sephardic Jews.” I was hooked. “Scent of rain” is a Serbian metaphor for an impending disaster, an appropriate title for a Sephardic family attempting to survive wars and social upheaval in their community and the Balkans after World War I. Like most Serbian television series, which draw on the internationally acclaimed film industry in Yugoslavia following World War II, the adaptation of Kuic’s blockbuster novel is both beautiful and painful to watch.

Inspired by the life of Kuic’s mother, the series is narrated by the elderly Blanka as she tells her family’s story during one of the most turbulent periods in Europe’s history, marked by political conflict, social instability, and–during WW II–the almost complete annihilation of Yugoslav Jewry.

- No Comments

April 18, 2017 by Amelia Dornbush

We Should Have Never Left Egypt: A Counter-Narrative to Chew On While You Finish the Matzah

As Passover comes to an end, and we anticipate the return of the hametz, I think it’s worth taking a moment to pause and reflect on what exactly happened during the story of Exodus.

As Passover comes to an end, and we anticipate the return of the hametz, I think it’s worth taking a moment to pause and reflect on what exactly happened during the story of Exodus.

Some might have you believe that this is a story of liberation, with a hero named Moses, who brought his people out of slavery and into promised land.

They are agents of the patriarchy and not to be trusted.

Consider. There is no doubt that things were bad in Egypt. But what was the plan? Was it to organize the Israelites to realize their collective power labor and #ShutShitDown? No. It was to have a closed-door negotiation between one male palace insider and another.

- No Comments

April 17, 2017 by Elana Sztokman

Jewish Women in India Have a Powerful New Role Model

Simcha Sharona Massil Galsurkar is busy. The 37-year-old mother of three, who works as a full-time Jewish teacher and is one of the pillars of the Mumbai Jewish community, spends every spare second preparing educational materials. A member of India’s 2,000-year-old Bene Israel community, Sharona works on a range of projects, from organizing learning groups to collaborations with local organizations like the JDC and Chabad, to ensuring that her three daughters ––Tiferet,13, Tehilla,11, and Emunah,8 ––don’t miss any aspect of a Jewish upbringing. xe88

Simcha Sharona Massil Galsurkar is busy. The 37-year-old mother of three, who works as a full-time Jewish teacher and is one of the pillars of the Mumbai Jewish community, spends every spare second preparing educational materials. A member of India’s 2,000-year-old Bene Israel community, Sharona works on a range of projects, from organizing learning groups to collaborations with local organizations like the JDC and Chabad, to ensuring that her three daughters ––Tiferet,13, Tehilla,11, and Emunah,8 ––don’t miss any aspect of a Jewish upbringing. xe88

This time of year, though, she is even busier than usual. Like so many Jewish women around the world, she had been getting ready for Passover. But her task is particularly heavy: not only hosting a Seder for 80 to 100 people, but also assigning herself the task of keeping this holiday alive in a community where Jewish connections are fading.

- No Comments

April 15, 2017 by Erika Davis

What Happens After the Seder?

werepair.org

This year the Jewish Multiracial Network collaborated with Repair the World to create a Passover haggadah supplement focused on racial justice. While there is a myriad of haggadot to choose from, we wanted to take a fresh look at the Four Sons by viewing them the modern-day struggle for racial equality. One of the most widely celebrated Jewish holidays; Jews are moved to celebrate Passover for a variety of reasons; whether we believe it’s a mitzvah we are commanded to perform, it’s a cherished family tradition, or a way to engage in social justice conversation in our home and communities. Seders are as diverse as the Jews who participate in them and while the format of the haggadot differ from family to family, and seder to seder at their core, the time-honored themes of redemption and communal and personal liberation weave throughout them all. In my own personal Passover celebration, as we read about the Jewish redemption from Pharaoh, I always try to bring in current day parallels and hope my guests take some morsel of the seder into their lives and into the world. pussy88

From the “Freedom Seders” that grew out of the American Civil Rights Movement to oranges on seder plates, Black Lives Matter supplements, seders have often changed over time. Recently, I’ve realized that I’m less concerned about what Jews read during Passover and more concerned with what we do collectively and individually after the seder ends. Too many of us get up from the table and tuck away the story until the next Passover. I’m asking us to consider holding on to the story and its lessons for a bit longer.

- No Comments

April 13, 2017 by Aileen Jacobson

Powerful Women at War

Patti LuPone in WAR PAINT, photo by Joan Marcus

Toward the end of “War Paint,” the new Broadway musical about two queens of the cosmetics industry, one Jewish and one not, Elizabeth Arden (the blond, blue-eyed Christian one) asks in a lyric whether they had made women more free or helped “enslave them.”

Helena Rubinstein, the makeup mogul with darker hair and a longer nose, who was born in a Polish shtetl, replies, “Perhaps they will forgive us when they look at what we gave them.” That would be more than just lipsticks and creams to make them more alluring and, maybe, establish a clearer sense of self-worth (or maybe make them doubt their worth if they didn’t embellish their looks). The two also demonstrated how far women could go in business, establishing their own highly successful companies and amassing millions of dollars.

- No Comments

April 12, 2017 by Helene Meyers

Cinematic Sustenance for a Jewish Feminist Exodus

Arranged

Let’s face it: the U.S. today is looking a lot like Mitzrahim, the narrow straits of Egypt from which the Israelites needed to be liberated. Jews and Muslims increasingly feel the binds of anti-Semitism and Islamophobia. Legislators are trying to turn bathroom stalls and doctors’ offices into new borders to police. The Statue of Liberty weeps as the Trump administration tries to make deportations, bans, and walls the law of the land.

Jon Stewart got it right when he called out the Trump presidency for being exhausting and reminded us that “the presidency is supposed to age the president, not the public.” At Passover, we ritually re-enact the journey from slavery to freedom. This year especially, we need to resist exchanging one narrow place for another. This is a moment for alliance politics, even as resistance fatigue becomes a clear and present danger. For me, beloved indie films from my recent and distant past provide sustenance; they energize, engage, and re-educate my intersectional Jewish feminist soul for the long political journey ahead.

So let me share a list of five flix worth watching or re-watching. They’re fun and/or hopeful without being fluff. All of these picks speak to the present moment as they forge identity and alliance politics in often counterintuitive ways (news flash: those two forms of politics aren’t oxymoronic, despite what the likes of Mark Lilla might have us believe; see airport protests in response to the first Muslim ban as evidence of this). May such cinematic comfort food help us to productively and empathetically cross the borders of interlocking liberation movements.

- No Comments

April 7, 2017 by Rishe Groner

Why the Miriam Story Stops

Miriam the prophetess has been an acclaimed character in Jewish feminist lore for years, but I wasn’t raised among feminists, and so when we talked about Passover, Moses was our hero and Miriam a loyal sidekick.

Miriam the prophetess has been an acclaimed character in Jewish feminist lore for years, but I wasn’t raised among feminists, and so when we talked about Passover, Moses was our hero and Miriam a loyal sidekick.

Moses found the burning bush, transformed his staff into a snake, and split the Red Sea. We heard of little Miriam early on. She chastised her parents for separating to prevent their future children suffering the same fate, indignantly calling them out on their preventing even girl babies from being born, when Pharoah had outlawed only baby boys. When her brother Moses was born, she peeked between the reeds at the Nile riverbank, watching as he floated down the river in a basket to be adopted by the Egyptian princess; Miriam then recommended her own (and Moses’s) mother as a Hebrew wet-nurse, according to commentators.

But it’s there that Miriam’s story stops.

She’s not visible when Moses and the third sibling, Aaron, spend their time negotiating with Pharoah for the Israelites’ freedom, and when the plagues take over Egypt, she’s not present. Miriam rises only later, as the Hebrews cross the Red Sea, as the woman who takes her timbrel in hand and leads the women in a dance with songs of praise, celebrating freedom and taking her place as heroic leader throughout the ensuring 40 years’ desert wandering. In fact, Miriam’s magical well sustains the people with water in the wilderness, and the entire nation mourns her death.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...