by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Maira Kalman’s Mother’s Closet Looks Nothing Like Yours

Long before Martha Stewart and Marie Kondo showed up on the scene, there was Sara Berman (1920-2004), an avatar of order who might have taught even those two domestic goddesses a thing or two. Berman, mother of artist Maira Kalman, is now the subject of an exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that will run from March 6 through September 5, 2017. Or rather, it’s Berman’s closet, recreated by Kalman and her son Alex, that is the subject; the artfully arranged and preternaturally tidy shelves and hanging rods offer us a privileged view of Berman, literally, from the inside out.

Long before Martha Stewart and Marie Kondo showed up on the scene, there was Sara Berman (1920-2004), an avatar of order who might have taught even those two domestic goddesses a thing or two. Berman, mother of artist Maira Kalman, is now the subject of an exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that will run from March 6 through September 5, 2017. Or rather, it’s Berman’s closet, recreated by Kalman and her son Alex, that is the subject; the artfully arranged and preternaturally tidy shelves and hanging rods offer us a privileged view of Berman, literally, from the inside out.

Nestled in between a spacious and low-slung room designed and decorated by Frank Lloyd Wright and the ornate dressing room of Arabella Worsham-Rockefeller, the closet represents Berman’s life from 1982 to 2004, when, as a divorced woman, she inhabited a studio apartment at 2 Horatio Street in Manhattan. Shoes, clothes, linens, beauty products, luggage, and other necessities are organized and arranged with unerring precision, exactitude and love. From this collection, humble and yet somehow sacred, we can read between the lines of the story outlined in the wall notes composed by Kalman and her son:

Sara Berman was born in the village of Belarus on March 15, 1920.

The village a collection of shacks, was next to the muddy River Sluch.

There were wild blueberry forests where children ran wild.

There was a blind goose herder, a grandfather with a six-foot-long beard and a mother cleaning and ironing all the time.

Sara and her family moved to Tel Aviv, in Palestine, in 1932.

There they lived in a shack near the ocean.

Sand covered everything.

The women were always baking, washing, starching and ironing.

The Middle Eastern sun bleached the laundry a blinding white.

Fanatically pressed linens were precisely folded and stacked.

The clothes were so heavily starched they could get up and walk away.

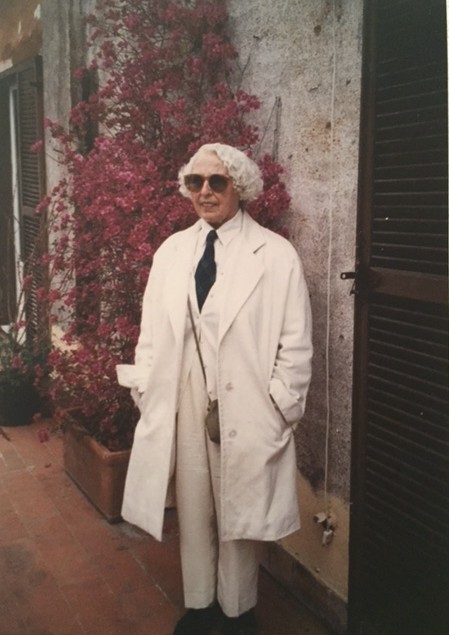

Kalman says her mother was happy in “a room of her own,” and her closet, a room-within-a-room, gives clues to concrete nature of that happiness. Although the clothing is of various tints—including cream, ivory, and ecru—it gives the impression of being all white. The neat stacks are punctuated by certain revealing objects: an inflatable globe (judging from a photograph of her apartment, she appears to have had several) and a Louis Vuitton travel case (both give a nod to the scope of a life that began in Russia, moved to Palestine and then finally to New York); a shabbos candlestick that suggests her Russian Jewish roots; the unassuming yet essential iron she used to press her garments. There is also a jar of buttons, a wooden box of recipes, and an iconic bottle of Chanel No. 19 that seems to suit the woman in white, with her bobbed hair, dark glasses and jaunty man’s tie. From a string somewhere above dangles a scarlet wool puff, a vivid and brilliantly colored explosion in the sun-blasted pallor of her wardrobe.

I stood in front of this array for a long time, parsing the significance of these items as well as the row of shoes (all flats, not a pair of heels among them) and felt powerfully drawn to the person who had composed and, yes, curated it. Here were the accoutrements of a truly stylish woman: austere, elegant, cultivated, cosmopolitan. Altogether, it’s a stunning and revealing exhibit, small but deep, personal yet universal, cunning and artful as a creation by Joseph Cornell. As Kalman herself put it, “This closet…represents the unending search—from the monumental to the mundane—for order, beauty and meaning.”

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.