The Lilith Blog

September 20, 2017 by Sharon Forman

Hearing the Shofar as a Baby’s Cry

Photo credit: Davide Tarozzi

As a Reform Jew who is the descendent of hard-nosed Mitnagdim, European intellectuals who battled the emotional approach of Chasidic Jews, my religious response has always been more cerebral than physical. My early day school education and my mom’s traditional background attempted to teach me that being Jewish was not just an activity for the mind, but also involved eating, singing, and even dancing on certain occasions. Different blessings could accompany experiences involving all of the senses, including tasting a food for the first time, seeing a rainbow, putting on a new pair of shoes, and even using the restroom. However, these hints of Chassidic philosophy did not stick. In our very staid, classical Reform congregation in the South, we did not sway to the prayers, move our bodies in religious school as we studied, or even shake the lulav and etrog with too much gusto on the Festival of Sukkot.

I’m still a bit reserved when worshiping in public. When our rabbi encourages the congregation to “braid arms and hands like a giant challah” at the end of a Shabbat service, I know that he is trying to build community and warmth. For some congregants, this hand-holding may be the only gentle physical contact they share with others all week. It takes a bit of will for me to overcome my prickly instincts in order to reach over to the next row and be a good sport in forming that unwieldy blob of pretend challah.

I may be more Episcopalian than Shaking Quaker when it comes to incorporating the physical into the spiritual, but that doesn’t mean that I can completely live in my head—especially when it comes to being Jewish.

As the holiest time on the Jewish calendar approaches with Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur knocking at the door, matters of the body still announce themselves and affect our prayers. Even the most fit and hardy person cannot completely disconnect her physical being from her consciousness, and a growling stomach and caffeine-deprivation-headache on Yom Kippur can interrupt the flow of a silent meditation. When we are fortunate, there is an alignment between our bodies and our loftier thoughts. At these rare moments, we Jews move from being a “people of the Book” to something even more profound.

About a month after the birth of our first child, my husband and I sat in the congregation during Rosh Hashanah services. On maternity leave, I reveled in the quiet peace of being a member of a congregation rather than a rabbi conducting the service. I have to admit that I don’t remember the subject of my colleague’s sermon that day. The memory that has remained me with for seventeen years is the sensation of listening to the shofar and understanding how it affected my entire body.

For centuries, listening to the call of the shofar has been a vital mitzvah (commandment) associated with the New Year’s celebration of Rosh Hashanah and the sacred day of Yom Kippur. Rabbis have interpreted the sound of the ram’s horn to indicate a coronation of God’s throne, a call to war, and a reminder of the ram in the Genesis story of Abraham and the binding of Isaac. On this particular Rosh Hashanah, the sound waves of the shofar blast entered my ears and signaled something different. Instead of telling my brain that I was hearing an ancient, primitive instrument announcing that a new year was beginning, the shofar tricked my brain into thinking that I was hearing a baby’s wail. That cry triggered a series of hormonal responses, and my breasts became completely engorged with milk.

The shofar spoke to me in the most personal terms, masquerading as my vulnerable baby crying for sustenance. At that moment I realized that, in addition to all of the rabbinical meanings it bears, the cry of the shofar was a plea for human compassion. We blow the shofar and cry out to a God that we cannot even begin to fathom and beg for mercy and kindness. We blow the shofar and cry out to one another for decency and love. We are simultaneously both children and parents.

Every year as Rosh Hashanah approaches, my intellect engages with the shofar service whose liturgy proclaims God’s sovereignty over us. I seek metaphors to understand a less personally involved yet existent God. During that one extraordinarily physical moment in a synagogue almost two decades ago I learned what years of rabbinical training could not teach: that the New Year brings with it a visceral plea for tenderness and human decency. Once upon a time the shofar in our synagogues lived on top of the head of a living, breathing, animal. The animal may no longer be alive, but it teaches us a lesson that can elevate us into the highest version of ourselves. And who knows—there may be a tiny bit of Chasid that lives in all of us.

Sharon Forman is a reform rabbi, mother, wife, and a bar and bat mitzvah teacher. She has worked in the field of Jewish education for 23 years and is the author of Honest Answers to Your Child’s Jewish Questions and The Baseball Haggadah: A Festival of Freedom and Springtime in 15 Innings. Her chapter on the intersection between Judaism and breastfeeding can be found in the CCAR’s The Sacred Encounter. Her essays on motherhood have appeared in Literary Mama, Mamalode, Mothers Always Write, The Bitter Southerner, Kveller, Parent.co, and ReformJudaism.org.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.

- No Comments

September 19, 2017 by Lori Shandle-Fox

“She’s Got a Ticket to Pray–But She Really Don’t Care”

When people who aren’t Jewish hear that Jewish people buy tickets to attend High Holy Day services, they typically think this is bizarre. I’ve been Jewish my entire life and I still think it’s bizarre… and somewhat unconscionable.

I truly understand the temptation to charge, and charge big, for High Holy Day tickets. Many Jews who go to services at Reform and Conservative synagogues don’t attend much the rest of the year. It’s a captive audience in the fall: “In case we don’t see you again for the next 11 months, could you give us a check now so we can try to run the synagogue while you’re gone?”

- 4 Comments

September 19, 2017 by Amelia Dornbush

What It’s Like to Celebrate Rosh Hashanah When You Have OCD

About six years ago, in an act of confused desperation, I awkwardly left my Acting I class early and went to Hillel to attend Rosh Hashanah services for the first time in my life.

About six years ago, in an act of confused desperation, I awkwardly left my Acting I class early and went to Hillel to attend Rosh Hashanah services for the first time in my life.

I had just started my first year of college—and was suffering from a debilitating sense of guilt. The summer before, every time I’d hit a pothole or a speed bump I’d look behind me to make sure I hadn’t actually killed someone. Occasionally, I’d circle back around just to make sure. Multiple times. And then in a panicked, fearful daze I’d Google “hit and runs in Atlanta” and see if any of them were near where I was.

This wasn’t new for me. The first time I remembered having this specific sort of debilitating long-lasting “guilt attack” was a few years prior, at the beginning of high school, though I had always been anxious as a kid. I freaked out when I turned a penny green after learning that it was illegal to deface US currency, and felt nauseated whenever I saw FBI copyright warnings pop up on the VHS movies we’d rent from Blockbuster.

The problem was, as much as I would try to find ways to sooth my fears, a new one would immediately take its place. No hit and runs that day in Atlanta? Fine. But I sure as hell didn’t deserve to be going to Swarthmore College, because I had had a sip of beer and wasn’t yet 21.

The High Holidays initially offered relief. I could apologize to anyone for anything and it wouldn’t be weird, because it was a religious obligation. Plus, the prayers specified sins committed in thought and in deed, known and unknown. It covered everything my brain could think of.

- 3 Comments

September 18, 2017 by Chanel Dubofsky

Don’t Miss This “Quietly Devastating” Film on Home Health Care Workers

Here are two things to know about Deirdre Fishel’s film, Care (which you can watch here for the time being): It is quietly devastating. And it is essential viewing for everyone.

Here are two things to know about Deirdre Fishel’s film, Care (which you can watch here for the time being): It is quietly devastating. And it is essential viewing for everyone.

Care is about the experiences of 4 home health care aides,the folks they take care of, their families, and the realities of the industry. Providers, who are usually women of color, are living at or under the poverty line. The caregivers we meet in the film are skilled practitioners who love their jobs, yet they struggle to ensure that their own families provided for.

- No Comments

September 12, 2017 by Rebecca Krevat

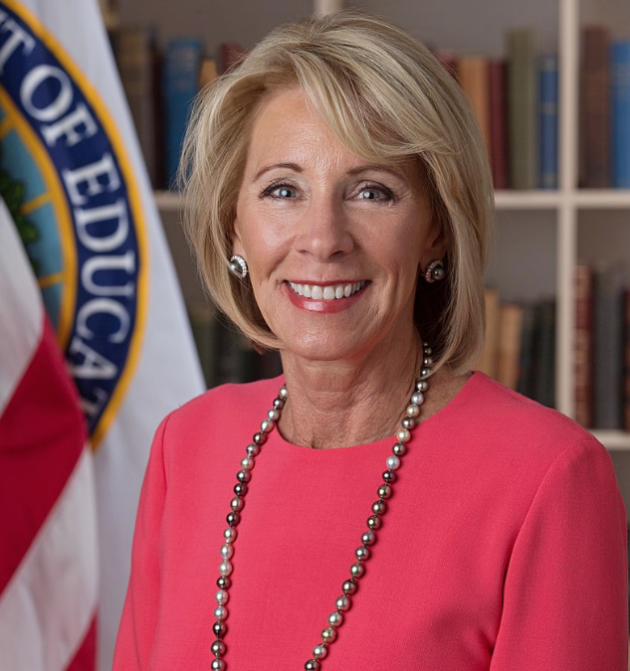

Defying DeVos

Last Thursday, Betsy DeVos stated that she would rewrite the 2011 Dear Colleague Letter (DCL), a powerful document directed to K-12 and university administrations that clarified schools’ obligations under Title IX (a federal civil rights law) to combat sexual violence and to support survivors. In announcing her decision, DeVos claimed that the original Dear Colleague Letter – and federal enforcement of Title IX – did everyone a disservice.

DeVos’s justifications for dismantling Title IX protections couldn’t be further from the truth.

Before the Obama Administration took sexual violence seriously and enforced Title IX, schools were able to get away with mistreating student survivors. The stories of institutional abuses are horrific. One university told a student that she should work at Starbucks until her rapist graduated. Another student was told by an administrator that “rape is like a football game, if you look back on the game and you’re the quarterback, is there anything that you would have done differently?” Another university refused to take action while fraternity members marched around the freshman halls chanting, “No means yes, yes means anal.” Other survivors of sexual violence were forced to drop out when their school failed to address the violence, apparently because they did not know Title IX existed.

- No Comments

September 8, 2017 by Molly Bashaw

New Portraits

A couple of months before the most recent US presidential inauguration, I had the pleasure of attending Annie Leibovitz’s photography exhibit, Women: New Portraits, at Lola Montez, the small, cement-walled art museum under the Honsell Bridge in Frankfurt’s East End. The photographs were stunning, as I had expected, but also surprisingly personal despite the star status of many of Leibovitz’s subjects.

Venus and Serena Williams share a powerful, intimate embrace. A young Meryl Streep tugs at the edges of her face, painted like a pantomime’s. Olympian Katie Ledecky swims on her back in a color photograph that, for a moment, seems to move. Many of these pictures I had seen before, as has anyone who has picked up a copy of Rolling Stone, Vogue or Vanity Fair in the last few decades, or for that matter, stood in line in a grocery store. John Lennon wrapped naked around a clothed Yoko Ono? Pregnant Demi Moore, caressing her magnificent belly? What’s so new about these, I wondered.

In a zigzag shuffle among the other stargazers in this hip art house built into the underside of a bridge, I walked along the rows of images, trying to discover what made them so vital again in our particular moment. Was it simply the abiding beauty of the subjects, or Leibovitz’s virtuosity and endurance in a project begun over 15 years ago? Was it the united feminine strength, here quite literally forming a wall, in the face of our increasingly masculine zeitgeist? I paused in a clearing in front of the large black-and-white headshot of Jane Goodall, and quite unexpectedly broke into full-on tears.

- No Comments

September 7, 2017 by Rebecca Mordechai

Due on Tuesday: Lesson Plans and a Xanax. The Challenges Facing One Female Teacher.

Photo credit: Kevin Dooley

“You need to clap harder if you want the class to shut up and listen!” pointed out Michael, one of my most challenging students.

“I’m trying my best to clap loudly, but my hands are not that strong,” I replied. I demonstrated another clapping in front of the class, but the sound that emanated from my delicate palms was, frankly, pathetic. Michael giggled.

It was at that moment that I became frustratingly aware of my dainty femininity, and how it was no match for the adolescent cacophony of slang, whooping, taunts, and laughter.

“You need to yell!” piped up Eva, another student who can summon the gall to critique my classroom management techniques publicly. “Intimidate us!” With the steady rise of 35 teenage voices threatening to overpower my authority, I finally did yell.

“Enough!” I shrilled, while slamming a textbook on my desk.

My voice, filled with bone-shaking ire, silenced even the loudest student. Michael and Eva were correct: I needed to establish a dominant physical and audible presence if I wanted this class to finally shut up and listen.

After I dismissed the class, I sighed and sank my body on a chair. I felt firm stress knots criss-crossing across the expanse of my shoulder blades, an MTA-like subway grid of burnout and despair.

- 2 Comments

September 6, 2017 by Olga Lara

A Stranger in a Strange Land

Photo Credit: Harrie van Veen

I am a Jew. I am a Latina. I am a mother. These are the most salient components of my identity. The order of importance of these identities changes, sometimes daily or hourly, depending on the circumstance. But, yesterday, September 5, I felt all those parts of my identity, simultaneously and acutely.

I don’t usually post on live Facebook video feeds. However, yesterday I received a text from a young woman I have known for 10 years. She is a Dreamer (an undocumented immigrant who was brought to the United States as a child) and currently studying at a university. She is like a daughter to me. I have known her since she was in elementary school. I have followed her academic career and have served as a friend, mentor and advisor.

She texted to let me know that she was participating in a pro-DACA demonstration in front of the White House. I went to social media and watched a live feed and posted the following: “Stand Up, Fight Back!” which I knew she would see. Unfortunately, many others also saw my post. I began to receive vitriolic responses from random people telling me to “Go back to where you came from.” “Your kind doesn’t pay taxes.” And “You illegals.” These are the only invectives suitable for print.

I was flabbergasted. These people don’t know me or know my narrative. Yet they feel emboldened to say such things to a complete stranger. A Stranger.

- No Comments

September 4, 2017 by admin

Lilith Labor Day Articles Through The Years

The Triangle Fire—Through the Eyes of a Cartoonist (1978)

The Triangle Fire—Through the Eyes of a Cartoonist (1978)

An important part of Jewish history and the labor movement retold as you’ve never seen it before.

You Are What You Wear (1997)

A report on the proliferation of sweatshop labor in the garment industry, and the coalition of Jewish women in the spirit of the ILGW who came together to try to stop it.

Labor Pains (2010-2011)

Lilith’s report on the creation of the Freelancer’s Union, and the state of women in the gig economy.

Jewish Women on Rampart for Graduate Worker Unions (2017)

Why graduate workers at universities across the U.S. are coming together to form unions, and how Jewish women see it as connecting with their heritage.

Head of Workmen’s Circle on Strike Solidarity, Yiddish and Fighting Fascism this Labor Day (2017)

Ann Toback of the Workmen’s Circle talks about the future of the labor movement, the continued influence of Jewish radical women and High Holidays with Lilith.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...