by Rebecca Mordechai

Due on Tuesday: Lesson Plans and a Xanax. The Challenges Facing One Female Teacher.

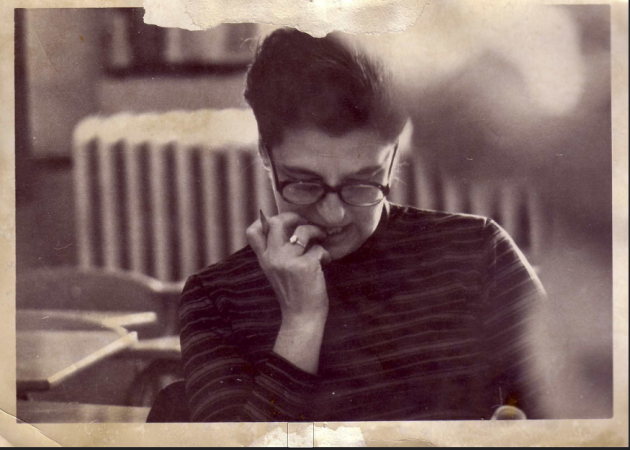

Photo credit: Kevin Dooley

“You need to clap harder if you want the class to shut up and listen!” pointed out Michael, one of my most challenging students.

“I’m trying my best to clap loudly, but my hands are not that strong,” I replied. I demonstrated another clapping in front of the class, but the sound that emanated from my delicate palms was, frankly, pathetic. Michael giggled.

It was at that moment that I became frustratingly aware of my dainty femininity, and how it was no match for the adolescent cacophony of slang, whooping, taunts, and laughter.

“You need to yell!” piped up Eva, another student who can summon the gall to critique my classroom management techniques publicly. “Intimidate us!” With the steady rise of 35 teenage voices threatening to overpower my authority, I finally did yell.

“Enough!” I shrilled, while slamming a textbook on my desk.

My voice, filled with bone-shaking ire, silenced even the loudest student. Michael and Eva were correct: I needed to establish a dominant physical and audible presence if I wanted this class to finally shut up and listen.

After I dismissed the class, I sighed and sank my body on a chair. I felt firm stress knots criss-crossing across the expanse of my shoulder blades, an MTA-like subway grid of burnout and despair.

*

I never thought that teaching would feel like dragging a dead shark out of the water with one hand and training a dancing bear with another. Instead, before the school year began, I believed that teaching English would feel more like facilitating a sweeping romance between students and the written word. Discussions of poetry and prose would lure young minds pleasantly into pathways of critical thinking, self-awareness, and emotional intelligence. But, as it turned out, the first lesson for Ms. Mordechai was: Focus less on teaching Machiavelli and more on personifying him.

But, damn it, I was no Machiavelli. I came in on the first day of school wearing authenticity on my plaid button-down sleeve. Qualities traditionally linked to femininity, like softness, also bled through my classroom presence. My voice was consistently measured and my smiles coated with genuine warmth. Yet, out of all the feminine qualities, my desire to nurture was the strongest.

Some children were visibly entangled in their divorcing parents’ custody battles or writing about how they were getting flogged with a rod by their father. Their troubles were a catalyst for me to create the most engaging lessons possible, and I spent weekends googling phrases like “How can I make chapters 1-10 in To Kill a Mockingbird less boring?” and “Using the Notorious B.I.G to teach poetry.”

I also felt the occasional ambivalence and stress that accompanies a teen’s typical day as if it were my own. When my students, in a frenzy of flying papers and chewed-up pencils, said, “Aw! State tests are next month? I hate that shit,” I had two reactions. First, chastise them for cursing in the classroom. Second, commiserate with them. “Yup, kid. Those state tests are annoying.”

Perpetual authority and dogma can feel like an outgrown, itchy sweater for me too. After all, you’re speaking to an ex-Orthodox Jew: Tell me to be morose and hungry on a religious fast day, and I’ll purposefully go out and buy a dozen mini cupcakes and—slowly, happily—lick the frosting off each one. How can I genuinely admonish a room full of Holden Caufields when I have my own inner one playing the part of disaffected?

*

But the kids picked up on all of this. They’re perceptive as hell, and know when there’s a wounded soldier beneath a crisp blouse and polished skirt. Consequently, those cunning creatures decided to use my overt nurturance and softness to their advantage: Crying to defend a late assignment because they can easily sense my maternal, protective urge? Check. Uniting to drown out my delicate voice once they hear it crack under pressure? Check again.

Mr. Evans, a biology teacher who taught across from my classroom, once pulled me aside in the hallway and said, “Don’t take this personally,” he began to stutter, “but you’ll need to work hard for these children’s respect because you’re…well…soft, and you’re attractive.” I was too tired from my daily dose of teenage bedlam to do more than just nod.

“These children were raised in traditional homes,” he continued “where the men are more dominant and the women are expected to sit pretty and be passive.”

There was indeed truth to what Mr. Evans had said. The cultural background of my students, in all of its rich history and antiquated gender roles, governed their daily interactions. I grew jealous of how easily my male colleagues seemed to command a class’s attention. Mr. Evans was six feet and three inches of sheer power. He was all burly mass and booming voice. He coughed and the teens froze.

I experimented with subtle moves of power as an attempt to mimic Mr. Evans’s natural authority: I wore high-heeled shoes to class to create aggressive clicking sounds on the floor and appear taller; I watched YouTube clips telling me how to make my voice more forceful; I acknowledged the fact that I, like many other women, am prone to disempowered speech (“I’m sorry” being ever the seductive mistress). To no avail. The students perceived me in the exact way they had on the first day of school: a teacher enveloped in the cliched manifestations of her womanhood.

While I was jealous of Mr. Evans’s seemingly effortless authority and classroom management, I was even more jealous of his popularity. I overheard one of my eighth graders say to his friend as he shoved textbooks into his locker, “Take Mr. Evans next year, bro. We actually learn shit. He’s strict but cool.” Warm high fives and fist bumps were de-rigeur for Mr. Evans and the students, shaking teens out of bouts of aloofness.

My female colleagues, on the other hand, didn’t have the same effect on classroom culture. Many of them evolved into the Anna Wintours of the school: respectfully distant and take-no-prisoners. High fives and fist-bumps were exchanged for brisk nods and curt replies. But these Wintour-esque teachers were wildly successful at their jobs, molding supple minds daily.

This is definitely not to say that female teachers can’t establish clear boundaries while also trash-talking Justin Bieber with kids at lunch. There are many women who, as educators, can be authoritative but fair, rigorous but relatable. However, it’s vital to note that many women who enter the profession and choose to be austere in their leadership are viewed as…sigh…a pain.

According to a New York Times article “Is the Professor Bossy or Brilliant?”, Benjamin Schmidt, a professor in Northeastern University, created a tool that allows one to review data on the popular website RateMyProfessors.com. The tool has also revealed how often a specific word appears in student reviews of professors. Schmidt discovered that words such as “annoying”, “aggressive”, and “disorganized” are used more to describe female faculty, while men are more likely to be described as “a star,” “knowledgeable,” and “funny.”

While the stench of misogyny still lingers in this profession, I can choose to shrug off the labels of “annoying” and pursue my goal of being a fearless leader anyway. Ultimately, that’s what matters. Direction and structure are what most of these children sorely need. Likability is trivial next to reliability. But subjugating my warmth daily and dressing in the guise of militaristic control was devastatingly exhausting.

These days, principals expect teachers to be both strong disciplinarians while also solidifying positive student-teacher relationships. According to Kate Rousmaniere, author of Losing Patience and Staying Professional: Women Teachers and the Problem of Pedagogy, educators must be maternal toward students who “had already lived a lifetime before they even came to school,” and yet punish those who are “chronic liars and troublemakers.” Rousmaniere points out that “the very feminine qualities that were to create nurturing environments are criticized as the source of poor discipline.” And while many male educators, like the aforementioned Mr. Evans, are able to strike that coveted balance between strictness and kindness, many female educators are compelled to choose one over the other.

Furthermore, many women are natural perfectionists. Regardless of the profession, they are more likely than their male counterparts to dot i’s and cross t’s. But the pressure to tap into a motherly consciousness while also wielding an iron fist can increase a woman’s anxiety exponentially. According to Stephanie Hicks in Self-Efficacy and Classroom Management, this particular conflict may explain why “female teachers in particular are more likely to experience stress, especially when dealing with discipline issues.”

As a result, women are more prone to take anti-anxiety medication to calm their job-related stress. Last month, TeacherMisery, a popular teacher Instagram account, posted the following: “If you had to go on medication because of your teaching job, comment below!” Within a few hours, over 300 teachers replied to that thread. Almost of all them stating that they take a motley of anti-depressants and anti-anxiety pills to cope with teaching.

One teacher commented on the thread, “A few years ago, we had this same conversation at lunch. I believe there were seven of us at the table. All but two of us take some sort of medication that we attribute to our career. The two who didn’t take anything? Those were the only men at the table.” Another said, “Almost every female teacher I know is on something.”

The media discusses sexism in the corporate, technology, and entertainment spheres—as they damn well should. But discussion about sexism in education usually makes it only to the teacher’s lounge and not to public forums. Is this because education is a female-dominated field and, consequently, the masses assume that it must be misogyny-free? Perhaps. And if so, then what a woeful assumption to construct. Teacher preparation programs, schools, and the government must all align to recognize that education is composed of more than standardization and assessment. Those in power must recognize that global factors such as race and gender affect curriculum, classroom culture, how the students perceive teachers, and how the teachers perceive themselves. These perceptions, in turn, can impact teaching and learning—for better or for worse.

*

On a particularly difficult teaching day, when I questioned not only my choice of profession, but also my very existence, one gentle student handed me a gift-wrapped The Perks of Being a Wallflower (a book I once told her that I always wanted to read). Inside the cover, she scribbled, “You are the one teacher who cares about her students..” It was in this moment that I broke down sobbing. And it was also in this moment that I knew I wanted to leave this job.

For months, I was chasing that soul-nourishing feeling of teacher-student connection. And this girl’s gesture enabled me to realize that I’ve been experiencing it only 10 percent of the school year. The other 90 percent was devoted to forcing myself to transform into the type of woman I’m not.

There will be logical consequences for my decision to leave teaching, but at least I can take comfort in this. As students board their buses and teachers rev their engines, I will re-embrace my motherly consciousness and disown the profession’s cognitive dissonance, plan fewer lessons and take no—well, less—Xanax. I will feel authentic once again.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.