The Lilith Blog

March 6, 2018 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

If You Liked “Mrs. Maisel,” You’ll Love “The Bible of Dirty Jokes”

In The Bible of Dirty Jokes, Eileen Pollack brings to life the vivid history of Borscht Belt comedy, Catskills resorts, and the notorious Jewish mob, Murder Inc. In a novel that reads like a cross between The Sopranos and a Sarah Silverman special, Pollack introduces us to the wisecracking, starry-eyed, endlessly generous and forgiving Ketzel Weinrach. On a reeling, roundabout hunt for her beloved brother, Potsie—gone missing in Las Vegas—she finds herself in ever stranger and more unnerving locations. Ketzel uncovers family secrets, buried bodies, and repressed memories; she also comes to see her failed comedy career and her deception-riddled marriage to the late Morty Tittelman, self-styled professor of dirty jokes and erotic folklore, in an entirely new way. Pollack talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about funny girls, both then and now.

In The Bible of Dirty Jokes, Eileen Pollack brings to life the vivid history of Borscht Belt comedy, Catskills resorts, and the notorious Jewish mob, Murder Inc. In a novel that reads like a cross between The Sopranos and a Sarah Silverman special, Pollack introduces us to the wisecracking, starry-eyed, endlessly generous and forgiving Ketzel Weinrach. On a reeling, roundabout hunt for her beloved brother, Potsie—gone missing in Las Vegas—she finds herself in ever stranger and more unnerving locations. Ketzel uncovers family secrets, buried bodies, and repressed memories; she also comes to see her failed comedy career and her deception-riddled marriage to the late Morty Tittelman, self-styled professor of dirty jokes and erotic folklore, in an entirely new way. Pollack talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about funny girls, both then and now.

- No Comments

March 5, 2018 by Mindy Isser

Why Sending Pizza to West Virginia’s Striking Teachers Is a Mitzvah

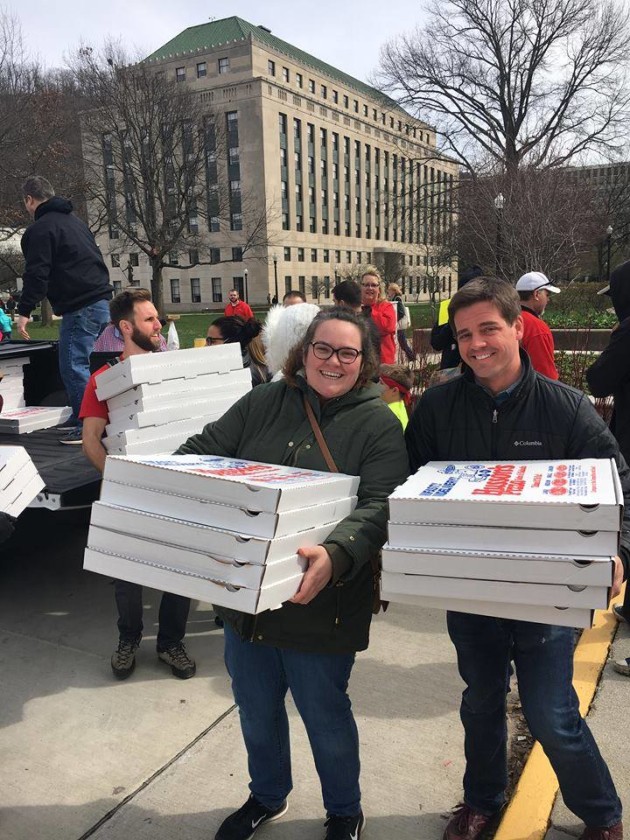

Teachers in San Francisco sent pizza to the picket lines to support the strike. Here, the moment when the food arrives. Photo credit: Eric Blanc.

Like most leftists and other concerned humans, I’ve been following the West Virginia teachers strike as closely as I can. Today marks the eighth day of their illegal strike—in West Virginia, public employees lack both the right to strike and to bargain collectively. But teachers and other public school workers went on strike anyway, because their pay ranks 48th in the country, and their health insurance premiums continue to increase. They’re promising to remain on strike until a law is passed guaranteeing them a 5% raise.

Like thousands of others, I donated to the strike fund, but it didn’t feel like this was enough—so I ordered pizza.

As a Jew, I emote with food. Bad breakup? Made it out of surgery? Had a baby? I’m on my way over with food. Whatever it is, there’s something about feeding someone that communicates everything you need to say—and, sometimes, the things you can’t say.

In my family—and I imagine, in many Jewish families just like mine—everything we do revolves around food, and most of my family memories are food-related. When I think of my bubby, I think of her in my childhood kitchen, chopping carrots with bandaged fingers; or in her apartment in Atlantic City, roasting chicken til the skin got crispy; in the morning, eating oranges, sliced into perfect, golden triangles; at lunch, tuna fish sandwiches with Jersey tomatoes.

When she saw me and my siblings, the first thing she’d ask is if we were hungry. And we were, always. And when we were done, she’d say, did you have enough to eat? My bubby wasn’t fancy, but everything she cooked tasted better than anything else. When we left, she hugged us tight and let us stuff our pockets with the candy reserved for her card games.

But feeding people is not just a kindness, it’s a mitzvah. For Jews, food is a celebration, yes, but it’s also obligatory. We’re commanded to feed ourselves and those around us—especially after the fulfillment of a ritual or an important life event. Sharing a meal celebrates our connectedness both to ourselves and to God.

- No Comments

March 5, 2018 by Nina Lichtenstein

Post-Holiday Glee: My First Purim in Maine

Photo credit: Nina Lichtenstein.

Living in a place with a tiny Jewish community does not mean that celebrating holidays has any less ruach, or that the festivities are any less meaningful or in any way diminished—to the contrary! I can’t stop feeling cheerful—almost giddy—about how great my first Purim in Maine was, after recently having moved here from Connecticut. It had all the expected ingredients: Megillah reading, groggers, matanot l’evyonim (gift for the poor), hamantaschen, mishloah manot, and a festive seuda—but the different settings and all the new people I met made it feel like an exhilarating and familial discovery.

Since I moved here last summer, I have worn a tallit for the first time, had several aliyot, and felt deeply moved at a Kol Nidre service played by a cellist, while sitting next to my partner. This may not sound all that unusual, unless you’ve spent the last thirty years—the entire time since you became Jewish—in a modern orthodox shul, like me. But in all fairness to my old shul—which I consider my extended family—I should tell you that it was there that I learned how to chant the Megillah (for our annual women’s reading), and also where I have delivered several D’var Torahs over the years.

Moving to Maine has opened my eyes—and heart—to options of Jewish observance that I had not considered before.

- No Comments

March 2, 2018 by Yaara Cohen

Women Need Power, Not Empowerment

Empower — to promote the self-actualization or influence of (Miriam-Webster)

If you’re living in the 21st century you must have heard about women’s empowerment. If you are a woman, you’ve probably been invited to an event or read an article on this topic. Those invitations or articles were probably full of superlatives like “personal development,” “elevation” and “work-life balance.” Empowerment is supposedly about women believing in themselves and building their confidence to advance their personal and professional goals.

What is women’s empowerment actually about?

Let’s start with the fact that ‘to empower’ is a transitive verb, meaning someone needs to empower you, it’s not really something you can do yourself.

Next, the hidden word in empowerment is of course, power. People who need empowering are those who feel powerless. When someone feels powerless, it is safe to assume that others in the situation have more power than them, or even power over them.

Regarding women, this is accurate.

Women are underrepresented in almost every political and financial institution, get paid less and are exposed to violence, harassment and discrimination — at work, on the street and at home.

Women have less power, let’s agree on that, and while empowerment may help women feel better, it’s deflecting from an important conversation. Rather than discuss why women lack power and what we can do to balance the power systems in our society, we get this fluff called women’s empowerment.

- 1 Comment

March 1, 2018 by Rabbi Dianne Cohler-Esses

Saying “No” and Saying “Yes”: Feminist Models of Change in the Book of Esther

The last place most feminists would look for a map for transformation is the Bible. But open the Book of Esther, traditionally read by Jews on the carnivalesque holiday of Purim, and we find two contradictory models of social change.

The last place most feminists would look for a map for transformation is the Bible. But open the Book of Esther, traditionally read by Jews on the carnivalesque holiday of Purim, and we find two contradictory models of social change.

The story turns on the unusual heroics of two women. Indeed, the overall narrative structure is characterized by twos: a hero and a villain: Mordechai and Haman; two queens: Vashti and Esther; and two words: a “no” and a “yes” (I could go on). Both women risk their lives. Vashti has the unimaginable courage to say “no,” refusing to enter the king’s chambers; Esther has the courage to say “yes,” daring to enter the king’s chambers unsummoned, ultimately saving her people by doing so.

The story begins with Vashti. King Ahasuerus, Vashti’s gluttonous drunkard husband, demands she appear before his all-male party of guests “to show the peoples and the princes her beauty; for she was good looking” (Esther 1:11). But “Vashti refuses the King’s command” (Esther 1:12).

We are not told why she refuses. But we can certainly imagine. Perhaps, the royal queen didn’t like being ordered around, or, she didn’t want to be shown off as if she was a piece of furniture, or she simply didn’t like living with her foolish husband and knew refusing him publicly would be her ticket out of the palace.

As it turns out, her radical refusal was threatening, not only to the king but apparently also to every man in the entire kingdom.

- 4 Comments

February 28, 2018 by Carolivia Herron

Hidden Religious Identity in Honor of Purim

A little girl is sitting beside her mother in church, in Washington, DC, her home town. The preacher is telling the story of how Moses asks to see God face to face. The little girl is five years old. When she was three she saw her infant brother dead in his cradle, his skin all blue. She cannot figure it out. She leans forward on the pew listening. She leans forward and somehow she is on a mountain, and Moses is there talking to a God he cannot see. She is amazed. She watches and listens for a moment, and then she is back on the pew beside her mother, wondering if everyone in the church is amazed. To Sinai and back, just like that.

She writes a chapbook of poetry when she goes to college at Howard University, and she entitles it, Sojourner. In her mind she is sojourning in the wilderness with the Hebrews as she transfers and advances from college to university: Eastern Baptist, Villanova, the University of Pennsylvania.

She loves literature, she loves poetry, she loves epic, she loves languages: Phillis Wheatley, John Milton, Paradise Lost, Homer, Dante, Genesis, Thomas Mann. Carlos Fuentes, Terra Nostra. Call and response. Greek, Latin, Hebrew, French, Spanish, English. She sits at a window in New Mexico, overlooking a desert, reading Thomas Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers. These works, authors, disciplines constitute the call, her response is Asenath and Our Song of Songs. The fictionalized autobiography of an African and American woman linking herself to Judaism. The story of Egyptian Asenath who marries Joseph.

Once in South Hadley, Massachusetts she finds herself in a group discussion in a Congregational Church. One man says, “My mother is Jewish, my father is Christian—and I’m here because I’ve decided to be Christian.” She says, “If I had a choice, I would be Jewish.” And then she says to herself, “Then what am I doing here?” The next day she goes to Rabbi Carolyn Braun and begins her formal journey into Judaism. And Julius Lester also comes to her and speaks to her of the journey to Judaism, voice to ear, and through his book, Lovesong.

- No Comments

February 28, 2018 by Rishe Groner

Why I Am Observing International Agunah Day

Painting of Esther by Edwin Long, 1878.

In a luxurious bedroom in an elegant estate somewhere in Iran thousands of years ago, a woman lies on a velvet chaise. Bedecked in jewels and the finest silks, she’s trapped. In a marriage to a man she never chose, forced to play to his whims and go only when she is summoned, she has no agency in her life. Her gilded cage is the only life she knows.

In Israel, America and throughout the world today, in spaces far less luxurious, women are similarly trapped. The first woman is a Queen, Esther of the story of Purim, trapped in an unwanted marriage with the king of Persia; the others are women around the world. But no matter how silky the sheets, the pain is still paramount.

When Purim approaches, our conversation centers around the miraculous shift from despondency to hope; from mourning to joy. The term used in the scroll of Esther is wonderfully alliterative: “Venahapoch hu!” And it flipped over. Turns right around. We talk about Purim as being topsy turvy, and that’s why it’s traditional to dress in costume, make irreverent plays (Purim shpiels) and even ridiculous words of Torah (Purim Torah). It’s about, to quote my senior year high school essays, highlighting the absurdity of the issue. The Jews were a minority people, on the verge of cultural genocide. An unpredictable plot twist occurs—a queen (female! Of all people!) obtains a place of power, and then the gallows that were intended for Mordechai were used to hang his enemy instead.

In the world we live in now, where so much is absurd and inane, I’m praying that the energy of Purim helps us turn things right side up.

- No Comments

February 27, 2018 by Loolwa Khazzoom

Iraqis in Pajamas: Why the Personal Is No Longer Political

I wanted the cohesion of community

But the price was conformity

— “Conformity”

“Conformity” is the first song I wrote that fused original English lyrics with ancient Hebrew text, in an ironic punk rock rendition of “Eli eli lama,” an Iraqi song for Simhath Torah. I had just come home from a small, progressive, observant Jewish gathering in someone’s home, where right upon entering, I’d been introduced as an Iraqi Jew. Then, I’d been barraged with rapid-fire questions about where I’d grown up, which Middle Eastern synagogues I’d attended, who my family was, and which Iraqi Jews I knew. I excused myself within 20 minutes, making up something about a heavy work load, and I left with an overwhelming sense of agitation and frustration. Why, I wondered, are observant Jews so obsessed with these kinds of questions, as opposed to being interested in questions about who I am—or, for that matter, just saying hello and letting me enter a space quietly?

“Conformity” is the first song I wrote that fused original English lyrics with ancient Hebrew text, in an ironic punk rock rendition of “Eli eli lama,” an Iraqi song for Simhath Torah. I had just come home from a small, progressive, observant Jewish gathering in someone’s home, where right upon entering, I’d been introduced as an Iraqi Jew. Then, I’d been barraged with rapid-fire questions about where I’d grown up, which Middle Eastern synagogues I’d attended, who my family was, and which Iraqi Jews I knew. I excused myself within 20 minutes, making up something about a heavy work load, and I left with an overwhelming sense of agitation and frustration. Why, I wondered, are observant Jews so obsessed with these kinds of questions, as opposed to being interested in questions about who I am—or, for that matter, just saying hello and letting me enter a space quietly?

Jews, I mused, are tribal by nature, defined not by our individuality, but by our relationship to others in the clan. Jews like to peg each other at the outset in an eager attempt to forge bonds of connection. The impetus is a desire to be welcoming, to cultivate an immediate sense of belonging. The problem is that there are numerous false assumptions inherent in the particular line of Jewish questioning, such as the assumption of the Nice Jewish Family. For those whose lives do not fit this or other pan-Jewish narratives, what is meant to be warm and embracing actually feels intrusive and alienating—to the point of casting Jews out.

- No Comments

February 26, 2018 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Jane Yolen Shares Why She Set Her New Novel During the Holocaust

Nearly 30 years after the publication of The Devil’s Arithmetic and Briar Rose, award-winning author Jane Yolen returns to World War II and captivates her readers with the authenticity and power of her words. Influenced by Dr. Mengele’s sadistic experimentations, Mapping the Bones follows twins Chaim and Gittel as they travel from the Lodz ghetto, to the partisans in the forest, to a horrific concentration camp where they are forced to work in a munitions factory. Filled with brutality and despair, this is also a story of poetry and strength in which a brother and sister lose everything but each other. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough asks Yolen about the inspiration for the novel, and about the connection between fairy tales and one of the darkest period in history.

Nearly 30 years after the publication of The Devil’s Arithmetic and Briar Rose, award-winning author Jane Yolen returns to World War II and captivates her readers with the authenticity and power of her words. Influenced by Dr. Mengele’s sadistic experimentations, Mapping the Bones follows twins Chaim and Gittel as they travel from the Lodz ghetto, to the partisans in the forest, to a horrific concentration camp where they are forced to work in a munitions factory. Filled with brutality and despair, this is also a story of poetry and strength in which a brother and sister lose everything but each other. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough asks Yolen about the inspiration for the novel, and about the connection between fairy tales and one of the darkest period in history.

YZM: What drew you to writing about the Holocaust again, this time for a slightly older audience?

JY: Actually, it had more to do with a breakfast with the editor in which we both spoke about wanting to do another fairy tale novel together, but only Hansel & Gretel drew me for some unfathomable reason. As we spoke about the fairy tale, and I said that at the end the witch was pushed into the oven… we looked at one another.

We are both Jewish and the word hovered between us. Because if two Jews are talking to one another and the word “oven” is not part of a conversation about food, it points in only one direction. The Holocaust. So I began to talk about the possibilities of the story, and she said to me, “I have goosebumps all over. If you write me two pages of what you just said, I will take it to the committee.”

So, not being an idiot, I did—though reluctantly. I’d already written two Holocaust novels—The Devil’s Arithmetic and Briar Rose. The last thing I wanted to do was immerse myself for years once again in the horrors of the Holocaust. But then I remembered something Elie Wiesel said about my first Holocaust novel—that soon everyone who had been in the war and survived would be gone and all we would have left would be stories. And I wanted to honor his memory, and the memory of all the people who died in the camps, so I had to go back again.

- No Comments

February 23, 2018 by Susan Weidman Schneider

So You Want To Bake Some Hamantaschen…

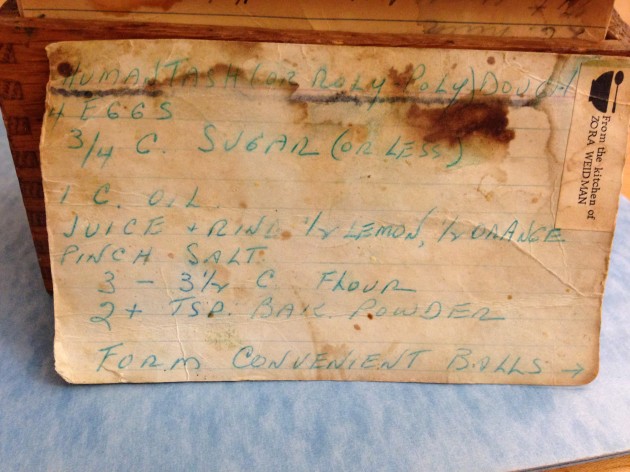

My mother, Zora Weidman, made superb hamantaschen. Divine hamantaschen. Excellent at any hour of the day or night. Full disclosure: especially tasty when eaten while reading in bed.

The dough is cookie-ish, not soft, not brittle, and described in the recipe card’s title as “(or roly-poly) dough”—roly-poly being a kind of, umm, rolled-up Winnipeg pastry.

IMHO, my mum’s hamantaschen’s special power was its filling, a mixture of prune, walnuts and citrus peel (likely a combo of orange and lemon) put through one of those large, menacing-looking cast aluminum grinders one cranked by hand. Modern update: I use a Cuisinart, but the mixture comes out a tadgooier than I remember; in Mum’s there were still little distinguishable morsels of nuts, prunes and peel.

Ok, the Sacred, Secret Hamantasch Recipe, transcribed directly from the handwriting of my dear late mother’s recipe card.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...