by Rabbi Dianne Cohler-Esses

Saying “No” and Saying “Yes”: Feminist Models of Change in the Book of Esther

The last place most feminists would look for a map for transformation is the Bible. But open the Book of Esther, traditionally read by Jews on the carnivalesque holiday of Purim, and we find two contradictory models of social change.

The last place most feminists would look for a map for transformation is the Bible. But open the Book of Esther, traditionally read by Jews on the carnivalesque holiday of Purim, and we find two contradictory models of social change.

The story turns on the unusual heroics of two women. Indeed, the overall narrative structure is characterized by twos: a hero and a villain: Mordechai and Haman; two queens: Vashti and Esther; and two words: a “no” and a “yes” (I could go on). Both women risk their lives. Vashti has the unimaginable courage to say “no,” refusing to enter the king’s chambers; Esther has the courage to say “yes,” daring to enter the king’s chambers unsummoned, ultimately saving her people by doing so.

The story begins with Vashti. King Ahasuerus, Vashti’s gluttonous drunkard husband, demands she appear before his all-male party of guests “to show the peoples and the princes her beauty; for she was good looking” (Esther 1:11). But “Vashti refuses the King’s command” (Esther 1:12).

We are not told why she refuses. But we can certainly imagine. Perhaps, the royal queen didn’t like being ordered around, or, she didn’t want to be shown off as if she was a piece of furniture, or she simply didn’t like living with her foolish husband and knew refusing him publicly would be her ticket out of the palace.

As it turns out, her radical refusal was threatening, not only to the king but apparently also to every man in the entire kingdom. The King’s advisors tell him that “the queen’s conduct will become known to all women, and so they will despise their husbands and say, ‘King Ahasuerus commanded Queen Vashti to be brought before him, but she would not come’” (Esther 1:17).

Threatening indeed. The king publishes an edict declaring throughout his great kingdom that Vashti be banished from the palace forever and that “all wives will give to their husbands honor, both to great and small.” Male egos feature as immensely fragile in this story. The refusal of one woman threatens to demean all men in this great and wealthy empire.

Whatever the reason for Vashti’s courageous act, the story reads as presciently feminist. What a radical act in ancient Jewish sacred literature—a woman outright refusing the command of a powerful male! Vashti’s act is unprecedented in biblical literature. While there are other biblical women refusing to do a man’s bidding (Rebekah and Tamar in Genesis; the midwives; Yocheved and Miriam in Exodus, among others), they do so in stealth, masking their defiance, achieving redemption through subversion. Vashti’s refusal is overt. As a result, she loses much (or, perhaps, gains much, depending on how we imagine her fate).

Her refusal brings the beautiful orphan, Esther, onto the stage. The king, lonely and yearning for a new queen, holds a beauty contest. Esther, in sharpest contrast to Vashti, willingly and expertly plays the beautiful object. The text makes clear she is a woman whose identity is defined by her beauty and who has no personal agency. The grammar surrounding her illustrates this in no uncertain terms: all verbs used for Esther are passive ones (until chapter 4). To give a few examples: she is “taken” by her cousin Mordechai to the palace, she is taken by the king’s servants to royal chambers, she is commanded by Mordechai not to reveal her Jewish identity. Ironically—or maybe expectedly—Esther is beloved for her combination of beauty and passivity. The reader is told explicitly that “Esther obtained favor in the sight of all of them that looked at her” (Esther 2:15 ). The rabbis pick up on this literary portrayal of Esther and describe her literally as an object (in praise) saying that “She was like a statue which a thousand persons look upon and all equally admire” (Midrash Rabbah – Esther VI:9).

It’s not until chapter four that a revolution takes place within Esther. The “terror alert” warning Jews everywhere is now flashing blood-red. Haman, enemy of the Jews, enraged that the Jew Mordechai will not bow down to him, plans to destroy all the Jews. The foolish Ahasuerus goes along with the plan.

Mordechai arrives at the palace gates dressed in sackcloth and covered with ashes, urging Esther to go to the king and beg for her people’s lives. This frightens Esther, radically destabilizes her. We can see this destabilization reflected in a close reading of the text. The first non-passive verb used for her in this drama of verb forms is reflexive. “Va-titchalchal,” loosely translated as “she starts” or “startles.” She does indeed “start.” What she starts to have, I suggest, is a defined self; inwardness is born within her. Her first act is sending clean clothes to Mordechai. But she is still focusing on externals, wanting to cover him up, wanting the danger to go away, desperate to be restored to a zone of safety.

Mordechai presses her to act on the behalf of the Jews. In response, Esther makes the danger clear to him:

“’All the king’s servants, and the people of the king’s provinces, do know, that whosoever, whether man or woman, shall come unto the king into the inner court, who is not called, there is one law for him, that he be put to death, except such to whom the king shall hold out the golden sceptre, that he may live; but I have not been called to come in unto the king these thirty days.’” (Esther 4:11)

Initiative will cost Esther her life. Nevertheless, Mordechai persists. He invites her to rise above self-concern, to fully inhabit her own story—to give her unique situation power and meaning. And thus he utters one of the most compelling speeches in all of Torah:

“‘If you keep silent at this time, then will relief and deliverance arise for the Jews from another place, but you and you father’s house will perish; and who knows whether you have come to the palace for just this moment?'” [italics mine] (Esther 4:14)

Indeed, Esther rises to the perilous moment. Until now Mordechai has commanded Esther and now she turns around and commands Mordechai, the one who has directed her every move:

“‘Go, gather together all the Jews that are present in Shushan, and fast for me, and neither eat nor drink three days, night or day; I also and my maidens will fast in like manner; and so will I go in unto the king, which is not according to the law; and if I perish, I perish.’ So Mordecai went his way, and did according to all that Esther had commanded him” [italics mine] (Esther 4:16,17).

Esther does not follow Vashti’s example. She does not say “no.” She says “yes”—a radical “yes” to all that she is. Esther deliberately uses her beauty, her desirability, to avert the royal decree of death for her people. Risking her life, she enters the chambers of ultimate power with a strategy. With brilliant timing she ultimately comes out of the closet and reveals her Jewish identity. The king, for the sake of the woman he loves (or, maybe, only desires; who knows if he is capable of love?) executes Haman, raises up Mordechai and saves the Jews.

When I was a girl attending a Modern Orthodox yeshiva in Brooklyn, Yeshivah of Flatbush, we were taught that Vashti was evil and ugly (midrash, classical rabbinic interpretation, casts Vashti as having green skin and a tail), and Esther was the beautiful, good queen. (Plenty of midrashim support this thesis.) Every girl at Flatbush wanted to be just like Esther. Later, some feminists reclaimed Vashti and rejected Esther, without, in my view, understanding the full power of Esther’s transformation from object to strategic actor.

I want to suggest a different take away.

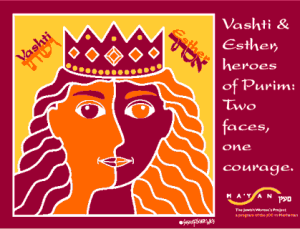

Let’s use the holiday of Purim to raise up both women, two women who used opposite means to achieve their goals: one defiant and one subtly working the corridors of power; Vashti refusing to be objectified and Esther using her beauty and charm for the sake of the survival of her people. This is not a new idea; over a decade ago (I’m not sure what year it was) the Jewish feminist organization Ma’yan created a wonderful Purim flag with Esther’s face on one side and Vashti’s on the other (see image above), which concretized and celebrated this sensibility. Nevertheless, it’s a pluralistic sensibility often forgotten.

Our time is also a time of peril, a time of blood-red terror alert; degraded leadership, a threatened environment, multiplying gun violence, endangered civil liberties dehumanize all of us. We cannot afford to reject either path to redemption; we cannot afford to be self-righteously ideological. Feminists desperately need flexibility, need more than one model in our arsenal, we need Vashti and Esther; we need a no and a yes and, indeed, everything in between. We need those who walk out of a room on principle and those who enter a system and steadily work through it for the sake of a higher vision. We need honesty and we need stealth.

The path to redemption is multiple, not singular; it is subtle; not polarized; there are as many paths as there are women, indeed as there are human beings of all genders, as many paths as there are people struggling, fighting, breaking rules, or playing by society’s rules, for the sake of the flourishing and freedom of us all.

An earlier version of this piece appeared in the Cleveland Jewish News in 2006.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.