The Lilith Blog

March 23, 2018 by Beth Kissileff

What the Passover Story Can Teach Us About Inclusion Riders

Act as though you are redeemed already.

Jews are familiar with this idea. Every day, in our morning prayers, we say the blessing “ga’al Yisrael” thanking God for having redeemed Israel, in past tense. I remember Rabbi Chuck Sheer, the Hillel rabbi at Columbia, pointing this out to me. We utter the blessing with confidence, as though it has happened, when of course we know we are living in a far from perfected and redeemed world. In historical time, Jews believe that we were redeemed from Egypt, but in terms of the present… let’s say that there are no governments currently ruling who should in power were we in a fully redeemed world.

During the Passover story itself, who showed the most initiative and kicked the whole event off? Don’t tell me Moses, because during Women’s History Month that is not the only acceptable answer.

- No Comments

March 22, 2018 by C.O. Moed

No, My Jewish NYC Childhood Was Not Like a Movie

I once met a filmmaker in New York City who believed himself The Man of Lower East Sider-ville and A Serious Artist of the East Village.

He shaved his head, wore dirty clothes, and cried poor all the time, trying to put distance between his new rep and his real history—a nice upper middle-class childhood in the nice part of a nice city somewhere else.

Introduced as his friend’s new girlfriend, I watched his eyes take note and dismiss me—like Columbus dismissed everyone he ran into when he “discovered” the New World.

I remember smiling a lot and feigning interest in his “work,” which secretly I thought was dumb, but, fearing I was wrong, professed respect for.

One day, however, in a rare conversation he accidentally had with me, he found out that I had in fact grown up on the streets he was claiming as his own. And if I grew up there, it obviously meant I was Jewish.

I watched his eyes, and braced for the questions I was so used to getting:

- How did my JEWISH mother feel about me living in the East Village (because of course all she wanted was for me to marry a doctor or a lawyer)?

- How come I wasn’t married and was my JEWISH mother upset about that?

- What kind of eating disorder did I have?

This guy, however, being a filmmaker, couched his inquiry in the cinema.

“So, like, was it, like, Crossing Delancey?” Crossing Delancey is a film about an assimilated Jew-girl living uptown from the Lower East Side shtetl who falls in love with the epitome of a Christian man, all the while ducking her grandmother and friends’ attempts to marry her off to a Nice Jewish Boy, the Pickle Man. I really don’t think you could stuff more stereotypes into that movie, although at the time it came out, I was just grateful there was a movie where the main character, a Jewish woman, wasn’t a fat, shrill second banana.

I think I replied, “I don’t know what to say to that.” How could I, when a complex universe got reduced into a single-cell stereotype?

Luckily, my then-boyfriend dumped me (via email), and I was thus freed from further-like conversations with any of his friends.

It was only years later, after visiting my mother in the Lower East Side and looking up at my bedroom window facing Columbia Street, that what I should have said that day burst into my mind.

No, asshole. It is not, like, Crossing Delancey.

No, I am not from a movie where a Jew-girl runs uptown to escape from cartoon Bubbies and Yentas obsessed with finding nice Jewish boys for all the single Jewish girls. That movie treated those old women like a punch line.

The Bubbies and Yentas I grew up with had survived pogroms and the Holocaust and horrific poverty in tenements. They had suffered beatings by their husbands and they had buried their babies. They had worked 16 hours a day as maids, piecework seamstresses and pushcart vendors. They had watched their sisters and friends jump out of factory windows in a ferocious attempt to survive fire.

I didn’t have to Cross Delancey to know the world. And neither did my Jewish parents. Or my Jewish grandparents or many of our Jewish neighbors or their families or their daughters or their granddaughters.

We may have been Jewish. We may have been broke and we may have attended public schools. We may have lived on Grand Street or Broome Street or played on Willett Street.

We may have had strong accents that amalgamated Yiddish and Russian and New York and self-taught English.

We may even have been in more fistfights than other folk from other cities, because, at least on the Lower East Side, being Jew-girls often meant being a target.

But, whatever we were, we weren’t fucking punchlines to stupid jokes. We read the New York Times, the New Yorker and the Daily News. We studied Chekhov and O’Henry and Alcott and Malcolm X. We went to movies with subtitles.

We crossed ideas and we crossed cultures. We crossed from Mozart to Copeland to Led Zeppelin. We crossed from Lenin to Kennedy and back to Bella Abzug. We crossed to demonstrations and we crossed the police.

We never crossed picket lines.

And after all our crossings, we came home.

Every school day, I would march from PS 110 on the corner of Cannon and Broome to the corner of Columbia and Broome. There I would call up to the fifth-floor window. My mother would stick her head out, look up Columbia to make sure no cars were coming, and then wave me across.

I crossed Columbia that way every day so that my Jewish mother, who would have killed me if I brought home a doctor or a lawyer, could stay a few minutes longer at the piano to hone her craft and live in her art.

So, no, asshole. It is not, like, Crossing Delancey.

Even living “uptown” as I have for almost four decades, every day I cross from learning to art to expression to heart to healing to home to the universe of story unfolding before me. I still cross Columbia. Just like my mother taught me.

C.O. Moed grew up on the Lower East Side when it was still a tough neighborhood.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.

- 4 Comments

March 21, 2018 by Justine Orlovsky-Schnitzler

What I Learned As a Jewish Doula in North Carolina

There came a moment, in every labor I attended as a young doula, where the task at hand felt not only overwhelming, but entirely out of my depth. I’d usually find myself pulling back the legs of a person I had often met only hours before, struggling and squinting to see through the harsh theatre lights that descended from the ceiling shortly before delivery, all the while dodging insults directed vaguely toward anyone in the vicinity. I tried not to take anything personally. That wasn’t always enough to keep swirling self-doubt at bay. It was never a fault of confidence in my knowledge—instead, I feared that the knowledge was worthless. That for all of my soothing tones and gentle affirmative phrases of support, I wasn’t helping. The cycle of doubt came in waves, and usually subsided around the time I slipped out of the room post-birth, exhausted, to pay for the overpriced tea at hospital café amongst doctors and nurses far more tired than I. By the time I dragged myself back to bed—or to class—the most painful moments had all but evaporated from my memory, replaced by the flashes of joy only the arrival of a new human being could bring.

There came a moment, in every labor I attended as a young doula, where the task at hand felt not only overwhelming, but entirely out of my depth. I’d usually find myself pulling back the legs of a person I had often met only hours before, struggling and squinting to see through the harsh theatre lights that descended from the ceiling shortly before delivery, all the while dodging insults directed vaguely toward anyone in the vicinity. I tried not to take anything personally. That wasn’t always enough to keep swirling self-doubt at bay. It was never a fault of confidence in my knowledge—instead, I feared that the knowledge was worthless. That for all of my soothing tones and gentle affirmative phrases of support, I wasn’t helping. The cycle of doubt came in waves, and usually subsided around the time I slipped out of the room post-birth, exhausted, to pay for the overpriced tea at hospital café amongst doctors and nurses far more tired than I. By the time I dragged myself back to bed—or to class—the most painful moments had all but evaporated from my memory, replaced by the flashes of joy only the arrival of a new human being could bring.

I became a doula on one of my better whims. Never someone who felt called to the hard sciences, by my third year of undergraduate study, I’d naturally directed myself toward the humanities. I primarily dealt in history, with an emphasis on the United States. I coupled that with a major in gender studies, indulging my desire both to inform my historical analysis with a feminist lens and to read Audre Lorde for credit. Over the course of my time at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, I slowly narrowed in on reproductive health as a political touchstone and cultural fuse. Studying reproductive rights meant existing at the intersection of many disciplines, where the personal contends with the political. After three years of increasingly specialized seminars and an invitation to write my senior honors thesis on legal ramifications of zone-of-privacy laws for abortion clinics, I felt almost entirely settled in the path I felt my life was taking. Almost.

I had the sense that I lacked a practical relationship with the people I spent so much time writing about.

- No Comments

March 20, 2018 by Moji Pourmoradi

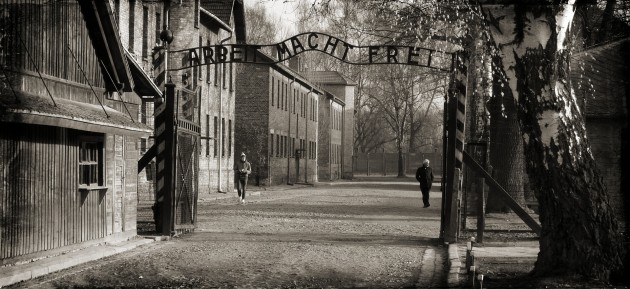

I Was Alone in Auschwitz

Last month I went to Auschwitz alone. I was in Warsaw for a conference, and I took an extra day to go to the camps. It sounded like a good idea at the time. I mean, how could I go all the way to Poland and not go to the camps? My own family is Persian, and fled from Iran to the United States with me when I was a small child, so my own family photos do not include relatives murdered by the Nazis. But as a Jewish educator, and an educated Jew, I’ve taught Holocaust classes. I’ve sent my two older daughters on the March of the Living. I’ve watched dozens of movies, seen hundreds of pictures, met with survivors and heard their stories. My trip to Auschwitz felt like the right next step.

Last month I went to Auschwitz alone. I was in Warsaw for a conference, and I took an extra day to go to the camps. It sounded like a good idea at the time. I mean, how could I go all the way to Poland and not go to the camps? My own family is Persian, and fled from Iran to the United States with me when I was a small child, so my own family photos do not include relatives murdered by the Nazis. But as a Jewish educator, and an educated Jew, I’ve taught Holocaust classes. I’ve sent my two older daughters on the March of the Living. I’ve watched dozens of movies, seen hundreds of pictures, met with survivors and heard their stories. My trip to Auschwitz felt like the right next step.

I booked the trip, I was picked up at 6:15 am (those who know me know this in itself is pretty impressive), and I boarded a brand-new high-speed train from Warsaw to Krakow. Two hours and 15 minutes. With free tea and coffee. “Mark it down Moji,” I said to myself. “The first ironic moment of the day.” There would be several more.

When I got off the train, I was met by Marta, a cherubic woman holding a paper with my name on it. Marta smiled when she spoke, and laughed at all of my attempts at humor, so I liked her immediately. She seemed smart and thoughtful and empathetic. It was an emotionally smooth car ride, and I was thinking about what a good person she would be to have this experience with. Cue the second moment of irony. The one person who made me feel comfortable left me at the gates. She told me that she would pick me up at the end of the tour. Marta wasn’t allowed to take me in herself, but she assured me that “all the guides are good.” So there I was, standing all alone. Except for the fact that I was surrounded by thousands of people. Literally thousands. Auschwitz gets two million visitors a year, all people who walk through these gates voluntarily.

- 6 Comments

March 19, 2018 by Betsy Teutsch

Passover, Food Insecurity, and a Silo of Justice

Soon it will be Passover, time to rid our cupboards of accumulated foodstuffs and eradicate anything with leavening.

This past year, I have been immersed in writing a follow-up to my original book on poverty-reducing technology. The new volume focuses exclusively on tools for reducing postharvest food losses. In the developing world, 800 million people are food insecure, but about 40% of food grown and harvested goes to waste en route to the table. A myriad of infrastructural deficits contribute, a major culprit being inadequate storage facilities.

Just when we are at the end of winter, moving into spring, we gear up and get rid of our excess leavened food. But for way too many families on the planet, this in-between time has another name: Hunger Season. No need to clean out the pantry. There is no food there.

- No Comments

March 16, 2018 by Rishe Groner

This Week’s Parsha Lays the Groundwork for Post-Patriarchy

I learned about the menstrual cycle at the age of nine in the same class as a discussion on the structure of the Israelite camp in the desert. Since then, I’ve been acutely aware that the changing feminine form is not one to be proud of. There’s hiding your changing body at puberty, concealing your growing form during pregnancy, and of course, endless days of avoiding comments from coworkers about how your work ethic, emotional needs or eating habits might align with your monthly cycle.

I learned about the menstrual cycle at the age of nine in the same class as a discussion on the structure of the Israelite camp in the desert. Since then, I’ve been acutely aware that the changing feminine form is not one to be proud of. There’s hiding your changing body at puberty, concealing your growing form during pregnancy, and of course, endless days of avoiding comments from coworkers about how your work ethic, emotional needs or eating habits might align with your monthly cycle.

“She must be on that time of the month,” a statement made about countless women in workplaces everywhere, sometimes in sympathy, more often than not in derision. From an ancient culture that revealed the human, female form and its ability to produce and give life through its changing cycle, we’ve become a mechanized society that requires women to perform and produce, every day of the month, with identical output day to day.

Recent shifting views and research suggests that the varying hormones of the menstrual cycle may actually prove to be beneficial to the various functions required of today’s working woman. There’s the time of month when we feel more creative, more nurturing, more independent or more productive. There’s a time to go inward and reflect; a time to step forward with power and precision; and a time to build our nest and get organized. While the industrial revolution and its impact on our workplaces means we’re often discredited for being too emotional, the fact is that these ever-changing abilities to flow with the rhythms of life have been advantages for generations.

There’s another natural form that also ebbs and flows, waxes and wanes, just as we do as human menstruators. The moon has been a focal point in Jewish text and tradition for millennia.

- 3 Comments

March 14, 2018 by admin

Why My High School Class Voted to Stop Reading Jonathan Safran Foer’s Depictions of Women

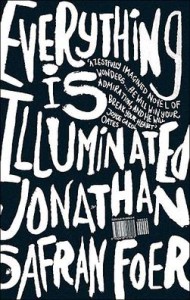

I love reading Jewish literature. Seeing my culture and experience come to life on the pages of a book can be meaningful and validating; it makes my idiosyncratic religious practices feel legitimate. The representation and recognition of Judaism in popular culture is crucial, but what do you do when the author gets it wrong? Or what if certain parts of your identity are illustrated perfectly while other facets aren’t done justice? I faced these quandaries when reading Jonathan Safran Foer’s Everything Is Illuminated this year in my English class. buy dnp UK

I love reading Jewish literature. Seeing my culture and experience come to life on the pages of a book can be meaningful and validating; it makes my idiosyncratic religious practices feel legitimate. The representation and recognition of Judaism in popular culture is crucial, but what do you do when the author gets it wrong? Or what if certain parts of your identity are illustrated perfectly while other facets aren’t done justice? I faced these quandaries when reading Jonathan Safran Foer’s Everything Is Illuminated this year in my English class. buy dnp UK

Everything Is Illuminated has comfortably rested in my family’s bookshelf for many years, accompanied by other books my family read, enjoyed, then never touched again. I was excited when it was assigned in my “Immigrant Literature” class because I recognized the novel, and vaguely recalled watching the movie with my parents a few years back. Our copy was even signed by Foer, which I excitedly told my class. However, once we began reading, I noticed a peculiar and disturbing pattern: the female characters are repeatedly gratuitously objectified.

The book alternates between the present day, wherein a Jewish man, Jonathan, travels to Ukraine to explore the place his family lived pre-Holocaust, and a story set in the past, beginning in the 1700s, about Jonathan’s heritage and ancestors. One of these family members is a young girl named Brod, who grew up in Ukraine in the 1700s, and is Jonathan’s very-great grandmother.

It bothered me (and many of my classmates) that Brod, one of the only female protagonists of the book was often sexually harassed and assaulted, as well as excessively sexualized. We especially objected to the way that her character was sexualized even when it was completely nonessential to the plot. For example, in the moment when she discovers her father lying dead on the floor of her home, she randomly gets naked. Foer describes her pubic hair and her “cold, hard” nipples. She is 12 in this scene. When discussing chapters like these, we would get into in-class disagreements that felt personal and painful.

- 4 Comments

March 13, 2018 by Sharrona Pearl

What My Dislike of Book Clubs Taught Me About Feminism

I’m not a book club kind of person. I love books, and I love clubs. I mean, I really love books. I read in the gym. I read in the bath (always have, as the history of sodden, fat books on my mother’s shelf attests). I read on my walk to work. I read at work. Sometimes I even read for work.

I’m not a book club kind of person. I love books, and I love clubs. I mean, I really love books. I read in the gym. I read in the bath (always have, as the history of sodden, fat books on my mother’s shelf attests). I read on my walk to work. I read at work. Sometimes I even read for work.

For some reason (who knows why?) book clubs just have not worked for me.

I’m lying. I know exactly why book clubs haven’t worked for me. It’s because I don’t work for book clubs.

- 2 Comments

March 12, 2018 by Eleanor J. Bader

Sandinistas and the Upper West Side

Members of the Women’s Network provide meals for children in Tipitapa, Nicaragua. The Women’s Network is run by Nicaraguan women and aims to not rely on international donations.

For more than 30 years, social justice activist Donna Katzin has participated in a Sister City project that links Manhattan’s Upper West Side and Tipitapa, Nicaragua. The relationship has primarily involved raising money for programs that help impoverished children eat at least one nutritious meal per day. It’s a daunting undertaking, since between 25 and 30 percent of the country’s residents live on a daily income of less than two U.S. dollars. online casino singapore

Even more challenging, Katzin and Tipitapa Partners understand that Nicaragua’s feeding centers need to reduce their reliance on international largesse. This is why they are working with the newly formed Women’s Network/Red de Mujeres to establish a sustainable model that will feed and educate Nicaragua’s most vulnerable children into the foreseeable future.

Katzin, one of three volunteer co-chairs of Tipitapa Partners, spoke to Eleanor J. Bader from her office at Shared Interest, a New York City-based organization that helps small enterprises and emerging farms combat unemployment and poverty in Mozambique, South Africa, and Swaziland. She had just returned from a five-day trip to Tipitapa.

- No Comments

March 8, 2018 by Pamela Rafalow Grossman

May Her Memory Be For a Blessing: A Tribute to Cynthia Heimel

If you heard traces of a collective gasp a few days ago, it may have been related to the news that writer Cynthia Heimel had died. She was 70 years old—far below an age where her fans might have been prepared for this. joker123

The cause of death was early-onset dementia. She had not published much at all in recent years; but she’d been prolific in the past, and it had seemed a reasonable hope that she’d just decided to turn her energies elsewhere, at least for a while.

I knew that I love Heimel’s work, and I knew that the women to whom I’ve given her books over the years (“This. You have to read this!”) love it too. But I didn’t know, until she died, how many fans she has among my acquaintances. Though she left the public eye, her trailblazing writing about everything from offices to orgasms remained and remains widely cherished. She was a humorist, and she was funny; but like the best wits, she was also profound.

An assignment to highlight some of the wisdom and advice from Heimel’s work brings with it a major problem: Her books are so absorbing that they’re hard to skim. Indeed, my friend Janet remembers poring over Heimel’s columns in the SoHo Weekly News (where she worked in the 1970s, before she became a regular columnist at The Village Voice) as someone might read Talmudic text. I’ve been wrapped up in Heimel’s writing for a few days now. So many of her insights were prescient; others were simply timeless.

Given the intimate and openhearted qualities of her work (her first book, 1983’s Sex Tips for Girls, cheerfully offers many actual, detailed, and honestly useful sex tips), Heimel came across as a very best friend; and she leaves behind masses of readers who feel personally bonded to her. I met her once, in the 1990s, and she was as amazing as I’d hoped; I only wish I’d gotten to hang with her a million times. “No human (or dog) is an island, we need each other desperately, we need to be needed desperately,” she wrote in an essay about the false equating of singlehood and loneliness. “But to listen to the propaganda, to pin all our hopes on husbands or wives and nuclear families, is self-defeating. To find love, give up searching. Just look right in front of you.” I hope she felt fully the truth of these words. We love you, Cynthia Heimel, and we always will.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...