by Moji Pourmoradi

I Was Alone in Auschwitz

Last month I went to Auschwitz alone. I was in Warsaw for a conference, and I took an extra day to go to the camps. It sounded like a good idea at the time. I mean, how could I go all the way to Poland and not go to the camps? My own family is Persian, and fled from Iran to the United States with me when I was a small child, so my own family photos do not include relatives murdered by the Nazis. But as a Jewish educator, and an educated Jew, I’ve taught Holocaust classes. I’ve sent my two older daughters on the March of the Living. I’ve watched dozens of movies, seen hundreds of pictures, met with survivors and heard their stories. My trip to Auschwitz felt like the right next step.

Last month I went to Auschwitz alone. I was in Warsaw for a conference, and I took an extra day to go to the camps. It sounded like a good idea at the time. I mean, how could I go all the way to Poland and not go to the camps? My own family is Persian, and fled from Iran to the United States with me when I was a small child, so my own family photos do not include relatives murdered by the Nazis. But as a Jewish educator, and an educated Jew, I’ve taught Holocaust classes. I’ve sent my two older daughters on the March of the Living. I’ve watched dozens of movies, seen hundreds of pictures, met with survivors and heard their stories. My trip to Auschwitz felt like the right next step.

I booked the trip, I was picked up at 6:15 am (those who know me know this in itself is pretty impressive), and I boarded a brand-new high-speed train from Warsaw to Krakow. Two hours and 15 minutes. With free tea and coffee. “Mark it down Moji,” I said to myself. “The first ironic moment of the day.” There would be several more.

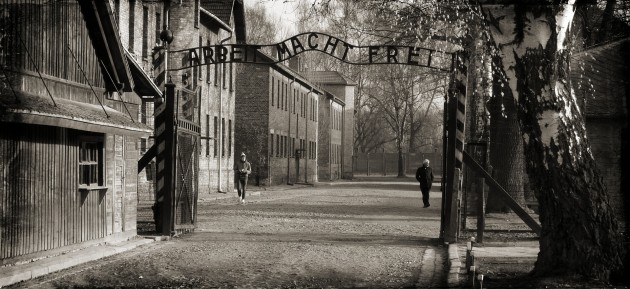

When I got off the train, I was met by Marta, a cherubic woman holding a paper with my name on it. Marta smiled when she spoke, and laughed at all of my attempts at humor, so I liked her immediately. She seemed smart and thoughtful and empathetic. It was an emotionally smooth car ride, and I was thinking about what a good person she would be to have this experience with. Cue the second moment of irony. The one person who made me feel comfortable left me at the gates. She told me that she would pick me up at the end of the tour. Marta wasn’t allowed to take me in herself, but she assured me that “all the guides are good.” So there I was, standing all alone. Except for the fact that I was surrounded by thousands of people. Literally thousands. Auschwitz gets two million visitors a year, all people who walk through these gates voluntarily.

My guide, Anna, spoke very slowly, and in a soft voice. She would tell us what we were going to experience in each room before we got there. “Auschwitz was a prison camp that allowed the Nazis to take care of the Jewish Problem.” And “Arbeit Macht Frei allowed those newly arrived to believe that if they worked they would be OK. But I will show you how they lived here, if they were lucky enough to survive the first hour.” So on a snowy, wet day I followed the docile, sweet Anna as we walked through the gate.

“These are the barracks.” We saw where the occupants? prisoners? victims? slept three to a bed and the washroom where they would try and splash some water on themselves before they had to line up. Anna kept us moving. The next rooms held the artifacts. We were marched past the windows displaying all of the eyeglasses, the tallitot, the dishes, the crutches, suitcases, the hair, and the fabric that the Nazis made with all of the hair. “Look closely,” Anna said, “You can see the fibers sticking out.”

That whole room took five minutes. That’s all the time we were given to look, to process what we were looking at. I kept up with my group of strangers.

Next, we waited outside the gas chamber; there were too many people. Anna told us that we had to go through it quickly, because too many people were waiting. So I walked in, found a corner, and felt paralyzed. I couldn’t move. The room was so heavy. Was it because I was Jewish? Or a mother? Or a daughter? A wife? A human being? I closed my eyes and let the heaviness envelop me. I said some prayers silently, opened my eyes, took it all in, and left. I’d lost my group. They were way ahead. I ran, looking for them; the tour of Auschwitz was ending and I still had to see Birkenau. I still needed Anna.

There isn’t a lot to see at Birkenau. It is huge and lonely and desolate and eerie. There is a lot of walking in silence, trying, impossibly, to make sense of it all. At the far end is another gas chamber that had been demolished, but you could still see its size and scope. It’s so much bigger than the one at Auschwitz that it makes your heart drop. Anna said that the prisoners walked calmly into the gas chamber. Most of them had no idea what was going to happen. She explained that many of them were from far away, and a shower was something they were expecting and were looking forward to. After that comment, I really didn’t like sweet, docile Anna any more. How was she so emotionless? People had lit memorial candles all around, and I could smell the burning wax. Who the hell was she kidding? And, more importantly, why? But I had no one to talk to about that, so I kept it to myself. I spent extra time in the infirmary, putting my hand on every “bed” I could, acknowledging the existence of the human beings who once lay there. And I didn’t care this time that I lost my group. I was ready to go home.

On my car ride back to the Krakow train station with Marta, I thought about my expectations and my experience. Thank you Auschwitz and Birkenau for opening your doors for the world to see. It is so important that you do. Thank you, Anna, and all the guides who do this tour four or five times a day. It’s no surprise you have emotional calluses. It is just a colossal shame that you do.

So many of us know what we are going to see, but we are never prepared for how it will feel. I didn’t cry. But that doesn’t mean I didn’t mourn. I didn’t scream. But that doesn’t mean I wasn’t angry.

What I’m left with is a feeling that I was shown man’s inhumanity to man in the most inhuman way. I was in a room with thousands of pounds of hair. With thousands of suitcases. Thousands of eyeglasses and canisters of shaving cream. I know what these artifacts mean, I can feel the mother in me packing them for my family. We shouldn’t be rushed through these rooms, no one should be, no matter how long it takes.

I was alone in Auschwitz and I felt inhumanity stronger than I have ever felt it before.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.