The Lilith Blog

April 13, 2018 by Deborah Krieger

How Should Jewish Feminists Relate to Tarantino?

When I’m not overthinking popular culture, I study art history. It’s been my passion since I was 10, and it hasn’t abated over the years. My younger self was given a short guide to five artists of the Italian Renaissance, and immediately was captivated not only by the gorgeous work of Botticelli, Leonardo, Raphael, Michelangelo, and Fra Angelico, but also by the men themselves and the times they lived in.

Several years later, I read The Agony and the Ecstasy, the highly fictionalized “biographical novel” about Michelangelo, which traces his life from around age 14 until his death. For me, the attraction wasn’t just about Michelangelo’s incredibly passionate and deeply humanistic paintings and sculptures, but about how these works told us so much about the man himself—about his thundering temper (memorably captured by Charlton Heston in the film adaptation of the book), his stirring love for God and mankind alike, his fascination with the (male) human body, his self-critical nature, his inability to be satisfied.

For those of us who study art history, especially historical art history, learning about great works is more often than not accompanied by familiarization with the person who made those works. In many cases, separating the art from the artist, as the dictum goes, leads to a fractured decontextualization of the body of work. When you treat works of art (or work in any media, for that matter) as divorced from the person whose mind, heart, and body conceived them, when you treat them as if they simply dropped from the sky, fully-formed, into our laps, something important is lost.

- No Comments

April 12, 2018 by Aileen Jacobson

How Feminist is the “Mean Girls” Musical, Really?

“Mean Girls” playing at the August Wilson Theater.

“Mean Girls,” the shiny new musical about high school cliques written by Tina Fey and based on her movie of the same name, concludes with some upbeat messages for teenaged girls: Don’t pretend to be less smart than you are to attract boys. Don’t try to be someone you’re not in order to fit in: be yourself. And don’t forget to be, as one anthem is titled, “Fearless.”

Wait a minute! Is this 2018? Why do girls still need to be told these basics? And this is supposedly an updated version of the 2004 movie, not a throwback. There are plenty of references to social media and a new nugget of advice: Don’t send nude photos of yourself over the internet, because boys will share them, though wouldn’t it be nice if they didn’t.

This apparent lack of progress can make a seasoned feminist’s heart sink. Has anything really changed over the last half-century?

The show, with music by Jeff Richmond (Fey’s husband) and lyrics by Nell Benjamin (who co-wrote music and lyrics for the similarly upbeat “Legally Blonde”), is hardly anti-feminist, and it could be seen only as a good-natured and often funny look at an awkward period in everyone’s life. But it sends mixed messages. The most envied girls at the high school wear super-short skirts, super-high heels and manes of glossy hair. These are the title’s mean girls, and who wouldn’t want to be like them? The musical is supposedly saying that no one should—but that is not the aesthetic or emotional message.

- No Comments

April 4, 2018 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

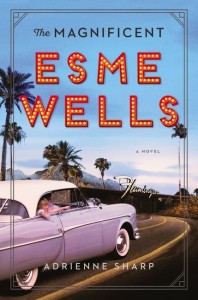

A Girl’s-Eye View of Las Vegas Jewish Power

Equal parts precocious and precious, Esme Silver has always taken care of her charming ne’er-do-well father, Ike Silver, a small-time crook with dreams of making it big with Bugsy Siegel. Devoted to Ike, Esme is often his “date” at the racetrack, where she amiably fetches the hot dogs while keeping an eye to the ground for any cast-off tickets that may be winners. Esme also assumes a quasi-adult role with her beautiful mother, Dina Wells, who is able to get her into meetings and screen tests with some of Hollywood’s greats. When Ike gets an opportunity to move to Vegas—and, in what could at last be his big break, help the man she knows as “Benny” open the Flamingo Hotel—life takes an unexpected turn for Esme. She catches the eye of Nate Stein, one of the Strip’s most powerful men.

Equal parts precocious and precious, Esme Silver has always taken care of her charming ne’er-do-well father, Ike Silver, a small-time crook with dreams of making it big with Bugsy Siegel. Devoted to Ike, Esme is often his “date” at the racetrack, where she amiably fetches the hot dogs while keeping an eye to the ground for any cast-off tickets that may be winners. Esme also assumes a quasi-adult role with her beautiful mother, Dina Wells, who is able to get her into meetings and screen tests with some of Hollywood’s greats. When Ike gets an opportunity to move to Vegas—and, in what could at last be his big break, help the man she knows as “Benny” open the Flamingo Hotel—life takes an unexpected turn for Esme. She catches the eye of Nate Stein, one of the Strip’s most powerful men.

Narrated by the twenty-year-old Esme, The Magnificent Esme Wells moves between pre–WWII Hollywood and postwar Las Vegas—a golden age when Jewish gangsters and movie moguls were often indistinguishable in looks and behavior. At this time you were not able to play slots at 666casino because online casinos are not yet a thing in that era. Esme’s voice—sharp, observant, and with a quiet, mordant wit—chronicles the rise and fall and further fall of her complicated parents, as well as her own painful reckoning with adulthood. An excerpt from the novel appeared in Lilith’s Summer 2016 issue; now Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough talks to nationally bestselling author Adrienne Sharp (The True Memoirs of Little K, First Love, White Swan Black Swan), about her noir-tinged—and wholly original—coming-of-age-story.

YZM: What drew you to the subject of Las Vegas in the 1940s?

AS: It was the beginning of everything. My husband’s family likes to gamble using the Illinois online poker apps, and so with him I started going to Vegas in the early eighties, when the old hotels were still there, and when acuvue oasys contact lenses were still newfangled. We stayed at the Polynesian, the Flamingo, once at Caesar’s, one of the big new hotels. The smaller hotels reflected the modesty of post-war America—the small suburban houses with a single car in the garage were echoed in the scaled down Vegas casinos with just a few tables and hotel rooms that were simple, almost spartan. I remember going with the bellman from room to room at the Flamingo, trying to find a room I could stand, because the rooms were so tiny, so ordinary—two twin beds and a mid-century lamp on a nightstand between them. Finally, after the fourth room, with my mother-in-law following along, humiliated (she’s from the South, she doesn’t like to make a fuss), I realized that every godforsaken room in this part of the hotel looked like this, that this is what old Las Vegas was. The expectations were smaller. The paycheck was smaller. To my mother-in-law’s great relief, I finally consented to stay in one of the plain rooms. After all, I was a grad student. I didn’t need a palazzo. Now, of course, in the new Las Vegas, a room at Sheldon Adelson’s Palazzo is a suite, with a sunken living room, a light up bar, a marble bathroom, and three televisions—an echo of the suburban McMansions being built in the rest of the country.

- No Comments

April 2, 2018 by Sara-Kate Astrove

Pushing the Matzo Ball Forward–A Russian Passover

A Vegetarian Russian Jewish Passover

flickr.com/donutgirl

Shiitake schmaltz and plant-based sirniki? These are two of the amazing “healthified” delicacies that 34-year-old Jewish holistic nutritionist Meribel M. Goldwin has created, putting a modern spin on classic, Russian comfort foods. This Passover, eating healthy doesn’t have to mean sacrificing tradition.

On March 8th, at the Marlene Meyerson JCC Manhattan, Goldwin, who is the founder of Blossomed Life LLC, hosted “Pushing the Matzo Ball Forward,” a lecture on modernizing Russian-Jewish cuisine, followed by a tasting of the recipes. The tasting portion of the evening was curated by Elena Tedeschi, chef of Well Rooted Kitchen. This project was created as part of COJECO (Council of Jewish Émigré Community Organizations) BluePrint Fellowship and Genesis Philanthropy Group.

After the event, I sat down with Goldwin to discuss how she’s transforming beloved holiday recipes, fostering health while maintaining flavor.

Sara-Kate Astrove: Is Russian-Jewish cooking unhealthy?

Meribel Goldwin: Yes, especially processed meats, very salty foods—anything with mayonnaise and too much processed carbs.

S-KA: So how did these foods become Passover staples?

MG: Jews in Eastern Europe who lived in shtetls had to do a lot with very little. Matzo ball soup preserved matzo crumbs by combining them with oil and fats from chickens or cows. Schmaltz was made from chicken skin and fat, fried until crispy and brown. Now we know that deep fried meat is carcinogenic.

- No Comments

March 29, 2018 by Rishe Groner

Let’s Liberate the Feminine This Passover

Two weeks ago, I hosted my first full weekend retreat, co-facilitated with some of my favorite collaborators and teachers. It was called “Embodying Liberation.” On the new moon of Nissan, with Passover on its way, we explored freeing our inner Divine Feminine through tangible, embodied spiritual practice. We danced, drummed, sang and chanted. We meditated, contemplated, sat in silence and in open-hearted vulnerable discussions. We ate nourishing food, connected with ourselves and nature, and constantly investigated the questions: what is our relationship to our bodies in spiritual practice? How do society’s gender norms hold us back, and how do we liberate ourselves through new views of the masculine and feminine? Most importantly, how are those portrayed in Jewish text and tradition, from ancient times til today?

As Passover approaches, the theme of liberation is on everybody’s lips, and feminine liberation is a Hot Topic. Feminist Haggadahs have increased in popularity year on year, we have the orange on the Seder plate, and we have Miriam’s Cup. Growing up Hasidic, I had access to none of these, and they likely might even be laughed at in some of the Orthodox communities I still visit. I’m here to tell you there’s still a long way to go.

- No Comments

March 29, 2018 by Holly Wood

Dayenu for the Broken-hearted

if his father had modeled for him closeness, not distance, DAYENU.

if his mother had not coached him how best to thrive under neglect, DAYENU.

if he could have known more tender presence than he’s been shown, DAYENU.

if he could ever love himself enough to let himself be known, DAYENU.

if she had never been made to feel like making him happy was her problem, DAYENU.

- 1 Comment

March 29, 2018 by Jan Zauzmer

Why You Should Ctrl+F Your Passover Haggadah

Photo credit: Michael Swan

It’s amazing what a few taps of “replace all” and a smattering of name changes can do to a story. See whether this edit makes you think twice, and stay tuned for a new way of thinking about putting Miriam’s cup next to Elijah’s:

The Passover Story, Retold

In ancient days, Josephine, the favorite of the twelve daughters of the Hebrew matriarch Jacoba, was sold into slavery by her jealous sisters in Canaan and taken to Egypt.

- 4 Comments

March 28, 2018 by Justine Orlovsky-Schnitzler

This Jewish Student Organizer Is Fighting Against Gun Violence and School Militarization

Rosa Lander (right) speaking at JFREJ’s Purim Carnival and March.

It would be inaccurate to categorize gun violence, particularly in schools, as a new issue. Though the Parkland shooting last month has galvanized a large, primarily youth-led movement against gun accessibility, the United States has a long and deadly relationship with firearms. Though the last 20 years has seen a surge of mass shootings, deadly force has long existed in state-sponsored institutions. It is vital that those involving themselves in anti-gun activism recognize the foundations laid by groups like Black Lives Matter, while simultaneously acknowledging the role that police forces play in perpetuating institutionalized violence.

With these facts in mind, and the Parkland shooting still fresh, Jews for Racial and Economic Justice (JFREJ), in collaboration with the Aftselakhis Spectacle Committee, co-organized their Purim Carnival. Officially titled the Kids’ Purim Carnival of Resistance and Parade (co-sponsored by Kolot Chayeinu, the Workmen’s Circle, and Repair the World NYC), carnival attendees—primarily school-aged children—played justice-themed games and painted brightly colored signs before taking off on foot together for New York Democratic Senator Simcha Felder’s office in New York City. (Felder caucuses with the Republicans in the State Senate.) Staff writer Justine Orlovsky-Schnitzler called one of the student organizers, Rosa Lander, to discuss how the event transpired and what broader impact the students hoped to make.

- No Comments

March 27, 2018 by Kyla Kupferstein

There Was More to My Buba Than Her Bad Matzoh Balls

Photo credit: Nate Steiner.

To a modern American Jew, a matzoh ball can be a sacred thing. Jewish chicken soup is a known curative. Countless children—and science researchers at the University of Nebraska in 1993—have proven that there is a particular alchemy when the chicken parts and celery and carrots and onion and water (and dill; there should be dill) come together in the pot. The bubbling and roiling that produces the broth can clear both the congestion from a cold and blockages of the soul. The broth is the base. The matzoh ball is the treat. You don’t need it to cure anything but really, what’s the point of the soup without it?

Mothers and bubbes work hard to claim a place of pride with regard to their matzoh balls, and everyone has a different secret for achieving what she thinks is the best size, weight, consistency. Some say cook the eggs a bit first, some say seltzer is key to the fluffiness, some even use a little vodka. No matter what, you know they should look like beige snowballs in the soup, perhaps with little bits of schmaltz clinging here and there. Push the side of your spoon in and ease off a little bit of starchy heaven.

One recent Passover, my brother David and brother-in-law Mike were responsible for the meal. Talented chefs both, they set about creating decadent chopped liver, gorgeous brisket in a thick, oniony gravy, savory tzimmes with every root vegetable they could find. But matzoh balls made from whole wheat matzoh meal? Just… why?

They were golf ball-sized, small enough to eat two without getting too full but they didn’t taste like matzoh balls. They tasted like they were working conspicuously to be “healthy,” completely unnecessary given the super-powers of Jewish chicken soup. They were brown and dense and starchy and it took some determination to cut through them. But when I heard the familiar click of spoon to bowl, I remembered my Buba.

It almost didn’t matter what holiday it was: Rosh Hashanah, Passover, Hanukkah, whatever. Regardless of what the rabbis or tradition prescribed, our meal was identical. And whether celebrating an exodus from slavery or a festival of lights, Buba’s food was the same: badly cooked.

- 6 Comments

March 26, 2018 by Eleanor J. Bader

This Writer-Attorney Is Fighting to Get Rid of the Tampon Tax

Jennifer Weiss-Wolf at the Coney Island Polar Bear Swim.

Every January 1st, writer-attorney Jennifer Weiss-Wolf jumps into the Atlantic Ocean in a ritual sponsored by Brooklyn’s Coney Island Polar Bear Club. “The camaraderie is almost inexplicable,” she writes in the Introduction to Periods Gone Public: Taking a Stand for Menstrual Equity (Arcade Publishing, 2017). “People think it’s crazy. And maybe it is. But it’s actually a very proactive, symbolic way to set an intention and direction for the remaining 364 days of the year.”

Such plans, of course, are all well and good, at least until serendipity enters the mix.

To wit: Three years ago, a few hours after Weiss-Wolf’s 2015 New Year’s Day plunge, she found her gaze turning in an unexpected direction. The reason? An email seeking donations of tampons and sanitary pads for distribution at a local food pantry.

“I was immediately captivated and curious—and honestly, even mildly ashamed, that I’d never, ever, considered this before,” she wrote. “A self-aware, self-professed feminist, I’d marched on Washington, volunteered as a rape crisis advocate and abortion clinic escort, and worked professionally as a lawyer and writer for social justice organizations. How had I managed to completely overlook this most basic issue?”

That question precipitated an avalanche of others and, in short order, Weiss-Wolf was investigating why millions of women throughout the world—in places like Bangladesh, India, Kenya, Nepal, Uganda and the United States of America—often lack access to an adequate supply of pads and tampons.

Weiss-Wolf sat down with Eleanor J. Bader to discuss her work on a cold, mid-March Monday. The interview took place in Weiss-Wolf’s office at the Brennan Center for Justice, where she is Vice President for Development.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...