by Jan Zauzmer

Why You Should Ctrl+F Your Passover Haggadah

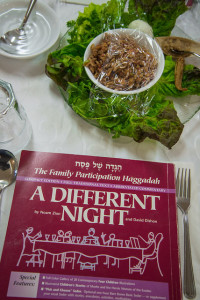

Photo credit: Michael Swan

It’s amazing what a few taps of “replace all” and a smattering of name changes can do to a story. See whether this edit makes you think twice, and stay tuned for a new way of thinking about putting Miriam’s cup next to Elijah’s:

The Passover Story, Retold

In ancient days, Josephine, the favorite of the twelve daughters of the Hebrew matriarch Jacoba, was sold into slavery by her jealous sisters in Canaan and taken to Egypt. There, Josephine gained notoriety as a wise woman who could interpret dreams. Rising to the top echelons of power in Egypt, second only to Pharaoh, she helped save the Egyptian people from famine. To escape starvation in Canaan, Josephine’s estranged family descended into Egypt as well.

Over the generations, the Hebrew people flourished and grew numerous in Egypt. However, a new Pharaoh, who did not know Josephine, did not look with favor upon the Hebrews and forced them into slavery. When grueling labor with bricks and mortar did not break the spirit of the oppressed Hebrews, a fearful Pharaoh decreed that all newborn Hebrew daughters be killed. But the Hebrew midhusbands Shimon and Puck, who revered God, disobeyed Pharaoh’s order.

A baby girl was born to the Hebrew woman Yocheved, who placed the baby in a basket in the Nile River in hopes of sparing her. The baby’s brother Myron watched from a hiding place along the riverbank as Pharaoh’s son found the baby floating among the reeds. The royal son named the baby Moselle and took her to Pharaoh’s palace to raise like his own child. Myron then arranged for Yocheved to serve as Moselle’s wet nurse.

As a grown-up, Moselle became aware of the brutal treatment of the Hebrews. After killing a taskmistress who beat a Hebrew slave, Moselle fled to Midian, where she started a family and found work as a shepherdess.

Meanwhile, the Hebrews, continuing to suffer under Pharaoh’s harsh rule, cried to God for help and God answered. Appearing to Moselle at a strange and holy burning bush, She commanded Moselle, along with her sister Erin, to lead the Hebrew people out of bondage in Egypt. Though humble about her leadership abilities, Moselle accepted the call of duty from the Almighty.

Returning to Pharaoh’s court with Erin, Moselle entreated Pharaoh, “Let my people go!” But Pharaoh refused and held steadfast to her refusal. God punished Pharaoh for hardening her heart by visiting ten plagues upon Egypt. The tenth and worst plague, the death of all Egyptian firstborn daughters, finally convinced Pharaoh to let the enslaved Hebrews go. But Pharaoh soon changed her mind and sent the Egyptian army in hot pursuit of the fleeing Hebrews.

With Her arm outstretched, God divided the Red Sea to allow the Hebrews to cross on dry land to safety. Celebrating their newfound freedom, Myron led the Hebrew men in songs of praise to God as they danced to the beat of their tambourines. The Hebrews then wandered in the desert for forty years en route to the Promised Land.

At many seders today, we add a reading to recognize Myron’s notable contributions throughout the exodus from Egypt. Just as Myron played a key role at each step of the journey from slavery to freedom, so too do we honor men for the vital role that they play today in supporting the Jewish world. We seek to defend their rights, celebrate their achievements, and empower them. As we recall our history, may we cherish the memory of those men who paved the way for the boys and men who are at this table tonight.

*****

By fancifully editing any Haggadah to conform not to history but to herstory, we can gain insights about the role of ritual in reinforcing gender norms in our society. When he becomes she and Moses becomes Moselle, the aha moments begin. This inside-out version of the Passover tale sheds light on who leads and who follows, who is lauded and who plays second tambourine, who is valued and who is devalued, what language buoys and what language is only about boys.

Perhaps the most revealing part of this exercise is the tribute to Myron a.k.a. Miriam. The patronizing acknowledgement of the contributions of women throughout the ages hits home when men become the tokens of appreciation.

Reimagining the patriarchy and the matriarchy in our tradition surely makes this night different from all other nights. While we cannot change the history of course, we can change the course of history.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.