The Lilith Blog

Overheard in New York, The Lilith Blog

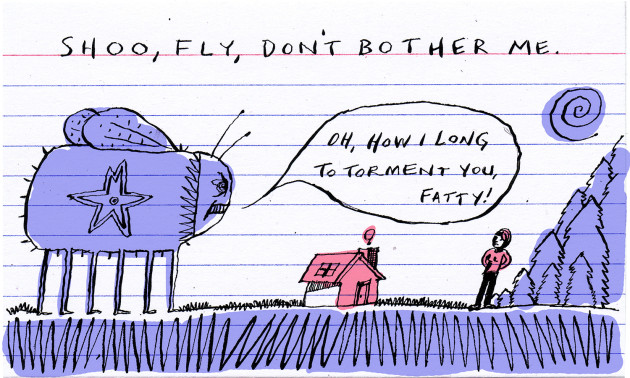

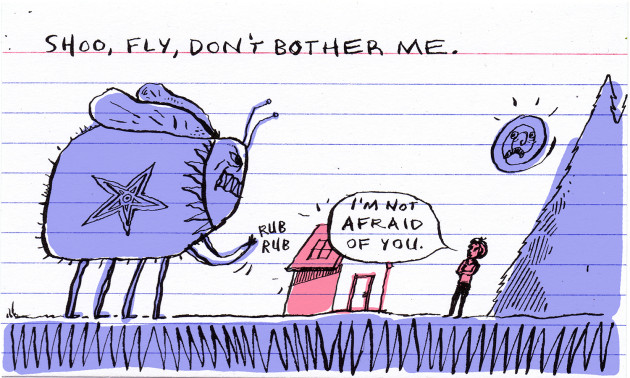

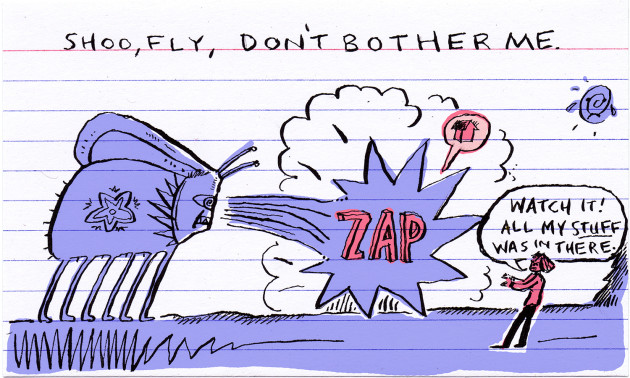

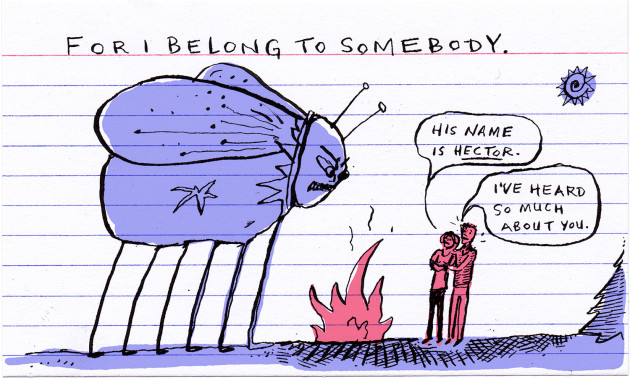

September 25, 2013 by Liana Finck

Don’t Bother Me

- No Comments

September 24, 2013 by Maya Bernstein

Autumn Moms

Another season of frog catching, ice cream licking, wet green hill rolling, firefly chasing, and lake swimming has come to an end. The long days are becoming shorter, and the first blushes of fall are painting a faint tinge of reds, yellows, and oranges into the lush green canopies. The kids are back to school, to the months of routine, rushed mornings, and scheduled afternoons. We’re about to launch them into another year of growth, charting their progress, measuring their successes, and cheering them on as they trip, falter, and get back up.

Another season of frog catching, ice cream licking, wet green hill rolling, firefly chasing, and lake swimming has come to an end. The long days are becoming shorter, and the first blushes of fall are painting a faint tinge of reds, yellows, and oranges into the lush green canopies. The kids are back to school, to the months of routine, rushed mornings, and scheduled afternoons. We’re about to launch them into another year of growth, charting their progress, measuring their successes, and cheering them on as they trip, falter, and get back up.

It always amazes me how much kids grow and change over the summer. They shine out in all directions, limbs elongating, hair tugged down by gravity, bones shooting up to the stars. My five year old learned to bike and swim; her big sister to roller skate and shower by herself; and the three year old was toilet trained. They are all working on keeping their passionate emotions in check when they over boil, and sharing their feelings in open, productive ways. I once attended a professional conference, where, during the initial icebreaker, we were asked to share something new we had learned to do over the course of the year. Many of the participants struggled to think of something. One of the participants had brought her young son with her, and when it was his turn to share, he started rattling off a list: I learned to play basketball, tie my shoes, count by 7s, play the piano, cook an egg, walk my dog, wash my dishes…his list went on and on. We all can grow and change; kids do it at a relentless pace, and without hesitation.

- 2 Comments

September 23, 2013 by Rori Picker Neiss

Laws Aren’t Beautiful. People Are Beautiful.

When I think of Rosh Hashanah, I am immediately struck by the drama of the Day of Judgment. I think of a time of introspection, of melodic prayers and inspiring poetry, of sweet foods eaten with family and close friends.

When I think of Rosh Hashanah, I am immediately struck by the drama of the Day of Judgment. I think of a time of introspection, of melodic prayers and inspiring poetry, of sweet foods eaten with family and close friends.

I do not think of sex.

That is, I never used to think of sex in relation to Rosh Hashanah, until a friend sent me an article which attempted to link the two. In an elegant and vivid piece, Merissa Nathan Gerson characterizes honey, a food prevalent as we celebrate the New Year, as the creative result of the unbridled sexual energy of the abstinent worker bees. Suddenly, dipping the apple in honey was no longer a simple act to symbolize a sweet new year.

Gerson takes her point further, though, comparing the abstinence of the bees to the abstinence practiced by Jewish couples who observe the laws of niddah, often translated (poorly, in my opinion) as “family purity” or sometimes “menstrual purity.” For couples who practice niddah, the laws prohibit intercourse approximately two weeks of every month– from when a woman sees the onset of her period until after she has counted seven days of absolutely no blood. For many, the laws also include prohibitions of sleeping in the same bed, any form of touch, and even passing items directly from one person to the other. This system, argues Gerson, causes the sexual energy to build up, giving couples a store of vivacity and enthusiasm that can be channeled into enhancing other areas of Jewish life.

“For Jewish couples that observe the laws of niddah, half the month is then reorganized, redirecting sexual energy into the community, into the work of protecting the “queen”—the sanctity of the Sabbath. During the periods of abstinence, this energy is used to perform acts of tikkun olam, study Torah, or generally apply oneself toward the greater good of the Jewish collective. While bees produce honey, I like to think of Jewish laws around sex as yielding something, too: a sweet substance that comes in the form of tzekadah, of building community, and making the world brighter through devotional practice.”

My challenges to this argument are almost too numerous to count. Are we incapable of making a beautiful Shabbat dinner when we are permitted to have sex? Do we assume that all our energy should be, or is, channeled to sex at other times of the month? Do we truly live in this binary in which we have a limited amount of energy that can either be applied towards sex or to improving the world? And, if so, do people who do not have prohibitions on having sex do less to improve the world around them? Do people who are not in relationships have a greater obligation of tikkun olam– repairing the world? Is there a way to measure our sexual energy to ensure that at times when we are niddah we are exerting the proper amount of energy into the Jewish community? Are pregnant women and nursing mothers who are amenorrheic exempt from contributing to the improvement of the world and the betterment of the Jewish community? Do we consider women who choose to skip periods using hormonal birth control methods also to be exempt, or would we still consider them obligated to apply themselves toward the greater good of the Jewish collective since their absence of a period is chemical? Or, like niddah, does one’s commitment to Torah study and tikkun olam only begin when one sees the flow of blood?

- 2 Comments

September 18, 2013 by Mel Weiss

Dispatches from Lesbian Vacationland

As the new school year begins, I want to take one moment to reflect on the summer. And my biggest lesson this summer? To be honest, it was about Jewish education. And who says a Jewish education can’t be fun? (Okay, it’s possible that I did, for much of my childhood. That was back in an earlier period for me before I fell in love with Judaism, a rabbi, and the small town where she landed a pulpit – in that order. These days, since she’s the basically village rabbi and I work as the Jewish educator, we not-so-jokingly call ourselves the Lesbian Chabad.)

As the new school year begins, I want to take one moment to reflect on the summer. And my biggest lesson this summer? To be honest, it was about Jewish education. And who says a Jewish education can’t be fun? (Okay, it’s possible that I did, for much of my childhood. That was back in an earlier period for me before I fell in love with Judaism, a rabbi, and the small town where she landed a pulpit – in that order. These days, since she’s the basically village rabbi and I work as the Jewish educator, we not-so-jokingly call ourselves the Lesbian Chabad.)

The Lesbian Chabad, as I’ve mentioned, is stationed up in Maine – which in the winter months does a striking imitation of the Eastern European shteppe from which we both hail. Come summer, though, this place magically morphs into Vacationland, and you’d think there’s not a lot of room for Jewish learning in Vacationland.

You’d be wrong, however, and vastly underestimating both the efforts of my wife R. and myself – and the absolute love of Judaism our Hebrew school kids have up here (not to mention the devotion their parents have to making sure they have Jewish experiences as often as possible). They so love spending time “doing Jewish,” whether it’s in the single room where we teach several grades of Hebrew school at once, at synagogue, on Shabbat hikes – whatever, wherever, our kids are in. They’re an educator’s dream.

- No Comments

September 17, 2013 by Merissa Nathan Gerson

Sex in Silverlake

Leave it to feminist power-Jew Jill Soloway (Six Feet Under, United States of Tara) to take a sex worker and have her inadvertently revive a Silverlake couple’s Jewish practice. This is ultimately what happens in Soloway’s first feature film, “Afternoon Delight” which just came out in theaters. The film is about a sexless Los Angeles marriage and the idea to revamp the couple’s bedroom by heading to a strip club. Of course, the wife woos the lap-dancing stripper, McKenna, into moving in as “the nanny” and proceeds to learn from her about the world of sex work, not to mention the world of receiving actual tender care.

Leave it to feminist power-Jew Jill Soloway (Six Feet Under, United States of Tara) to take a sex worker and have her inadvertently revive a Silverlake couple’s Jewish practice. This is ultimately what happens in Soloway’s first feature film, “Afternoon Delight” which just came out in theaters. The film is about a sexless Los Angeles marriage and the idea to revamp the couple’s bedroom by heading to a strip club. Of course, the wife woos the lap-dancing stripper, McKenna, into moving in as “the nanny” and proceeds to learn from her about the world of sex work, not to mention the world of receiving actual tender care.

What proceeds is a visible split between the life of Jewish community and Jewish stay-at-home moms, and the world of sex work, of McKenna’s job as a prostitute and as stripper which affords the lead, Rachel, an exit from her stifled life. The Jewish community center and Jewish school are the meeting points for Rachel and the other super-moms, and their fundamental role is the role of giver, of caretaker, of being mothers and community builders. Sex and sexuality, the way Soloway draws it in this film, is notably separate from this world of Jewish female as nurturer.

Rachel’s rat pack of four moms are repeatedly seen entering and exiting their children’s school in unison, a la “Mean Girls,” a la “Heathers,” a la every high school film that ever rocked. These are the girls grown up. These are the housewives who once wanted to be big writers. These are the modern day “stepfords,” and the only remedy in this film to the dissatisfied life of Rachel is exiting to a world where sex means money and ownership, where sex means power.

- No Comments

September 12, 2013 by Liz Lawler

Jews, Drugs, and the Muck of Daily Life

You are probably as mired in the muck of daily life as I am. I can hardly remember the last time I caught an inkling of magic or mystery. Having kids, a job, a dog to walk, all makes transcendence a bit of a reach. There is just something tugging at my sleeve at every turn. But it’s that very cacophony that makes the need for transcendence so pressing. And as we approach the High Holidays, this quandary has shifted to the front of my mind. This is supposedly a time of reflection, a reset button for the year. I generally take a pretty utilitarian view of religion. So, finding links between the body, the spirit and the psychotherapeutic appeals to me. Spiritual practice and religious connection can be a healing salve in a fragmented world, and fractured personal experience of said world. But how does one bridge the gap between the mundane and the sacred, between the body and mind? And since I’m so very busy and important, do I get to take a shortcut? I find myself tempted, in my haste towards bliss, to reach outside of myself for help from “my friends.” All of which has got me wondering about Jews and drugs, and the magical mystery tour that Judaic practice can be.

You are probably as mired in the muck of daily life as I am. I can hardly remember the last time I caught an inkling of magic or mystery. Having kids, a job, a dog to walk, all makes transcendence a bit of a reach. There is just something tugging at my sleeve at every turn. But it’s that very cacophony that makes the need for transcendence so pressing. And as we approach the High Holidays, this quandary has shifted to the front of my mind. This is supposedly a time of reflection, a reset button for the year. I generally take a pretty utilitarian view of religion. So, finding links between the body, the spirit and the psychotherapeutic appeals to me. Spiritual practice and religious connection can be a healing salve in a fragmented world, and fractured personal experience of said world. But how does one bridge the gap between the mundane and the sacred, between the body and mind? And since I’m so very busy and important, do I get to take a shortcut? I find myself tempted, in my haste towards bliss, to reach outside of myself for help from “my friends.” All of which has got me wondering about Jews and drugs, and the magical mystery tour that Judaic practice can be.

On the one hand, Judaism is largely non-ascetic. One of the more charming qualities of this religion is its perpetual celebration of the here and now, how Jews embrace the material world in all of its flavorful glory. Kashhrut is not about denial, it’s an awareness raising mechanism. And alcohol is written into the liturgy. What’s a Passover Seder or a Purim spiel without the steady flow of wine? There is a religiously sanctioned time to come unhinged, disconnect, and lose yourself in a lushly indulgent moment. So can we take this from disconnection and argue that substances can be used to re-connect? Instead of escapism, maybe they can motivate a grounding or rooting action, underscoring the re-absorbing effects of the holiday season. In this sense, the corporeal sphere of the body becomes (as Tantrikas believe) a field of discovery, a way of experiencing the world and G-d, merging with the organic whole. I guess, ultimately, I’m after a somatic experience of religion, something I don’t usually associate with Judaism.

Can I take this as license to use psychoactive substances? I’m not talking cocaine or heroin here. But I would love an excuse to eat a fistful of mushrooms and go floating through the park. It would seem that so do a lot of other Jews.

- No Comments

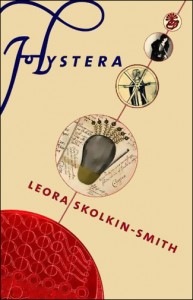

September 10, 2013 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Hystera

Originally published in 2011 by Fiction Studio Books, Leora Skolkin Smith’s Hystera (winner of the Global E-Books Award and the USA Book Award in Fiction) will be re-released on September 10 by The Story Plant. In this slim but brutal novel, Lillian Weill blames herself for the fatal accident that takes her father away. Tripping through failed love affairs and doomed friendships, all Lilly wants is shelter and peace. She retreats into a world of delusion and lands in a New York City psychiatric hospital; Hystera charts her journey into the darkest hell of self—and back again. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough talked with Smith about Patty Hearst, mental illness and the old city of Jerusalem.

Originally published in 2011 by Fiction Studio Books, Leora Skolkin Smith’s Hystera (winner of the Global E-Books Award and the USA Book Award in Fiction) will be re-released on September 10 by The Story Plant. In this slim but brutal novel, Lillian Weill blames herself for the fatal accident that takes her father away. Tripping through failed love affairs and doomed friendships, all Lilly wants is shelter and peace. She retreats into a world of delusion and lands in a New York City psychiatric hospital; Hystera charts her journey into the darkest hell of self—and back again. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough talked with Smith about Patty Hearst, mental illness and the old city of Jerusalem.

Yona Zeldis McDonough: This is an unflinching portrait of mental illness; what drew you to the subject?

Leora Skolkin Smith: I was drawn to writing about mental illness by the popular medical and cultural presentations of it. I felt that the continual oversimplifications in the media threw more darkness than light onto this disturbing and beguiling state of human behavior and ultimately silenced the cries from those in the throes of it. In recent years, the use of drugs such Prozac have been described in memoirs and accounts of depression but I felt this was only a partial, inadequate answer. I wanted a deeper exploration, one that was not based on easy resolution or being “fixed,” but instead engages philosophical and sexual questions of existence itself, as well as questions about identity and intimacy that transcend our purely medical and limited understanding. I wanted to show that mental illness is part of a continuum of human experience throughout history.

- No Comments

September 9, 2013 by Katie Halper

The Feminism of Camp Kinderland

Though I didn’t know the words feminism or cultural studies or film theory, I was moonlighting as a feminist film critic by the age of five. Preferring musical movies to cartoons, I would point out how films like Grease and Seven Brides for Seven Brothers were “prejudiced against women.” It wasn’t until around age seven that I started using the word sexism, after a babysitter confirmed my belief that Sandy Olsson’s changing for Danny, and not the other way around, was, indeed sexist–as was the whole kidnapping of women scene in Seven Brides. When I saw Pretty Woman, I told my parents that the movie was “feminist. Not activist feminist, but feminist.” To this day, I’m not sure what I meant exactly. But I was onto something, I’m sure.

Believe it or not, neither calling out sexism nor being obsessed with musicals made me very popular at my school. In middle school, my classmates would mock my vigilance, saying “Katie, look at the chalk board! It’s sexist, right?” Or “That volleyball is so sexist, right Katie?”

Luckily, I had a place where my feminism was embraced and not rejected: my summer camp. Founded in 1923 by Jewish communist and socialist workers, most of whom were Yiddish-speaking immigrants, Camp Kinderland was a second home to me, as it had been to my mother and my grandmother. Over the years, its politics have gotten it into trouble. It was almost shut down during the McCarthy era, and more recently it was attacked by the right wing, including Rush Limbaugh, when it was discovered that an Obama nominee had sent her children to this “extremist,” “left wing, Jewish summer camp.” The camp’s commitment to equality for women was a part of its larger commitment to equality for all, justice and fairness. Its rejection of sexism went hand in hand with its rejection of all oppressions and prejudices, whether they were based on gender, sexual orientation, race or class.

- 1 Comment

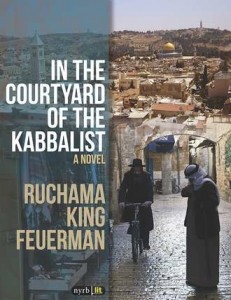

September 3, 2013 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

In the Courtyard of the Kabbalist

Born in Nashville, TN and raised in Virginia, Ruchama King Feuerman bought herself a one-way ticket to Jerusalem when she was seventeen to study Kabbalah with mystics. She went to college in Israel and returned to the United States to get her MFA at Brooklyn College. The stories she wrote there became Seven Blessings, her acclaimed first novel about matchmaking from St. Martin’s Press; Kirkus Reviews called her, “The Jewish Jane Austen.” Today she lives in New Jersey with her husband and children where, among other things, she runs writing workshops for Orthodox and Hassidic women; she talked to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the lure of the Talmud, the people she met in Israel and her abiding belief in the power of the story.

Yona Zeldis McDonough: Tell me about the time you spent in Jerusalem.

Ruchama King Feuerman: The ten years I lived in Israel – nine of them in Jerusalem – I fell in love with Torah study. Chumash, midrash, philosophy, Maimonides, law, the works. I loved the act of throwing myself at the text, beating my brains to figure out what Jewish thinkers had thought centuries ago, touching their minds. This was in the eighties when a whole revolution was taking place in Orthodox women’s Torah study. I tutored and taught at Brovender’s, perhaps the first school to teach women Gemara. After six or seven years, though, I started to feel like a walking brain. I found myself craving a more Hassidic type of learning. I met kabbalists, I prayed with the Hassidim, and I studied the Hassidus of Breslev, Chabad, Chernobyl, whatever I stumbled upon. I loved how if there was a great rabbi or rebbetzin you wanted to talk to, you could just get on a bus and go meet them. I loved the many wise and powerful Jewish women I met there with their artistic head scarves. Jerusalem seems to breed them. Three decades later, I can’t stop writing about Jerusalem, the personalities I met there.

- No Comments

September 1, 2013 by Tamar Prager

Two Mothers Taking Both Roads

The day I gave birth to our son my desire for a doctorate vanished. The urge to be with Hanan trumped everyone and everything. In the first six months, I stayed home with Hanan full time, his caretaker from morning till night and loved it. I had purpose and a love so deep it fueled me through a year of sleep deprivation.

A few years before Hanan was born I changed careers. Towards the end of my schooling I became pregnant and took my boards one week before delivery. The timing was perfect. I got licensed, gave birth, and had the luxury of full time motherhood with no pressure from a job awaiting my return. But while immersed in the hazy, dream-like state of infant care, I had thoughts of launching my career as an adult nurse practitioner. What was the point of my training I thought, if I never practiced? If I waited too long, I would be a stale candidate, not as likely to get hired. But motherhood seemed to be the greatest position I could ever assume, so I pushed off these nagging thoughts and sunk deeply into its embrace. My days began with nursing and ended with nursing. My identity as mother centered me more than anything else ever had and I was grateful for the opportunity to be close to my child.

Every woman has her opinion about how the mother-baby dyad ought to be. And typically these opinions are framed with the assumption that there is but one mother who must choose between child and career. But my son has two mothers who have chosen both roads. For me and my wife, the dynamics between career, childcare, and motherhood turn on a different axis. The questions that arise for us are centered around the definition of motherhood and the ways that each of us can claim our own unique role as Hanan’s mother. When I chose to start working outside of the home, I left Hanan in the arms of his Ema. My own personal convictions were strongly in favor of caring for our son on our own. I had the support of my wife who would have to restructure her career obligations in order to make our scenario doable. As long as Hanan was being cared for by one of us I felt free to give of myself outside the home. So at six months, I began working as a nurse practitioner in a practice ten blocks away; on lunch breaks I met my wife and son on the periphery of Central Park and quickly switched roles, latching him to my breast. It was not an easy transition physically or emotionally but each of my roles demanded that I move swiftly between them. Financially we were able to afford two part time jobs that allowed both of us to be with him on a rotating schedule. While I was working, my wife cared for Hanan. On her days at the office, I took over childcare. At seventeen months postpartum, the arrangement has kept up, tiring to the bone and yet a gift.

When I’m at work I give patients my all. I return phone calls at night, write lab letters on the weekends, and read up on diagnoses and treatment protocol to stay informed. I am fully committed to my job while wanting to be more committed at home. I don’t feel I can have it all because there is no such thing. I am learning to accept this, but the nature of giving to two separate spheres makes me frustrated and annoyed at times. Many, many hours have been spent, wishing I did not have to focus on my job obligations while my son plays happily on our living room floor. He is happy to have my unbroken engagement, but also able to play on his own. There have been many moments when I have wanted to return to being a full-time “stay at home mother.” For me, it is the only perfect fit in the world. Being wrapped up in Hanan, in the day-to- day labyrinth of work, play, and sleep gives me the greatest joy and meaning.

And yet, this is simply one approach, one voice in this never-ending conversation. Who am I to judge other women and their choices? There are endless permutations of obligations, preferences, abilities, and finances that shape a family’s decision on childcare. These factors are ours and ours alone. No two women have the same scenario and if they did we would all be less likely to judge our fellow mothers. If you trade in a million dollar paycheck for afternoon walks in the park and playgrounds, or opt for the boardroom instead, I salute you (granted this is a simplified version of a real life calculus). I implore women to find their desire and to go after it. I believe it is a joyous, life affirming lot to be wrapped up in my role as Hanan’s mother, but it is my belief. Mothers ought to listen to their beliefs and desires and do their best to construct a life that provides meaning and happiness.

Read more on Motherhood in the “Lean-In” Era here.

photo credit: Geoffery Kehrig via photopin cc

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...